In January, as my Drukair flight from Bangkok approached Paro International Airport in Bhutan, I was on the alert. To visit this small Himalayan Buddhist kingdom, you must surrender (after a multicountry relay from the U.S.) to a landing that is famously tricky, so much so that fewer than two dozen pilots are certified to make it. It requires maneuvering the aircraft through a long, winding valley between mountains as high as 18,000 feet to reach a short runway that comes into view only moments before touchdown. The wings of our plane, resplendent with a white dragon on a yellow and orange background, appear to be almost brushing the steep, darkly forested slopes on both sides. (Druk means dragon in Dzhongka, the Bhutanese language, and is the country’s spirit animal.) Beyond is the Himalayan range, which for 300 miles traces Bhutan’s border with China. I glimpse only a couple of snow-covered peaks before we descend deeper into the valley, but I still sense the giant mountains’ potent, ineffable presence.

This moment was a long time coming. Bhutan has a richly ambivalent attitude toward outsiders. Wedged between China and India, never colonized or conquered, it was self-protectively closed for centuries. The first tantalizing bits of information about it came out in a 1914 National Geographic article by a British representative to the 1907 coronation of Ugyen Wangchuck, the first druk gyalpo (dragon king) of Bhutan.

Road construction began only in the 1960s, tourism and the international press were allowed in 1974, and television and the internet arrived in 1999. Then came the obverse problem: As Bhutan advanced to the top of many bucket lists—a “last Shangri-La,” strongly Buddhist, culturally intact, and, since 1972, governed not by the harsh exigencies of gross domestic product but by the alluring principles of what it calls Gross National Happiness —hikers swarmed its trails and spiritual gawkers converged on its sacred rituals. But the Bhutanese government took the proverbial yak by the horns and last September put into effect a steep new visitor tax: $200 per person per day, on top of all other expenses. It was at once a stern rejection of mass tourism and a way to fund sustainable development projects. This, for me, was finally it: The right moment to experience a marvel of a country without, I hoped, a tour group in sight.

We are a traveling party of four, including the actor Alan Cumming, all of us brought together for this adventure by a mutual friend with Bhutan connections. “It’s rare to come to a place where you have culture shock,” says Alan. “And I like that. I’m feeling intrepid.” All our sentiments precisely. Despite our cushy appointments—a guide, driver, and minivan await outside the airport—we “Bhutaniers” (as we’ve anointed ourselves and our WhatsApp thread) are at once exhilarated and slightly discomfited by our imminent arrival in a place for which we have no frame of reference, no context whatsoever.

The pilot nails the landing and we find ourselves in an anachronistic, modern commerce–free world. Neither advertising nor international brand names are allowed to mar the cultural narrative in the airport. Bhutan’s king, the progressive and photogenic 43-year-old Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck (who happens to be on our flight and whose glamorous wife, Jetsun Pema, has been dubbed the “Kate Middleton of the Himalayas”), has declared the airport an art gallery. You’re greeted by large photographs of Bhutanese plants and birds at passport control, and of Bhutanese citizens at the two baggage carousels. Your bags spin around exquisitely realized models of two of the country’s major historic structures, the Punakha Dzong (dzong means fortress and usually includes a monastery) and the Trashi Chho Dzong, since 1968 the seat of the government. Instead of, say, an Hermès boutique, there’s a life-size diorama against one wall depicting a smiling red-robed monk, wild animals at his feet, seemingly smelling the flowers. A large sign next to it says, simply, “Bhutan. Believe.” Believe in what?

So begins an adventure the mysteries of which will expand and intensify as our efficient itinerary unfolds: six days, three towns, three hotels, as many fortresses, monasteries, and shrines as possible, and a famous hike. Lovely Dorji Bidha, our guide, spots us quickly. “I’m starstruck,” she tells Alan. She introduces us to our driver, Nima Dhendup, and we’re off. The capital, Thimphu, our first stop, is an hour away along a narrow, winding mountain road.

I am struck by the ubiquity of traditional Bhutanese houses, handsome baronial structures set amid meadows and wintry rice paddies. And by the prevalence of national dress, the men’s gho and the women’s kira (largely obligatory except for private or weekend wear). Different types of prayer flag ripple everywhere across the landscape like so many ancient antecedents of Christo’s Gates: some white, for the deceased, arranged vertically; others, for luck and health, multicolored and hung horizontally. With every gust of wind, the prayers printed on them are said to spread throughout the world for the benefit of all sentient beings.

In our first hotel, the Druk, a comfortable, Bhutanese-owned property on Thimphu’s central square, a sign announces the spa services: “Have you ever floated on a cloud?” On the schedule, after lunch at Shambhala Café (its name is Sanskrit for a mythic Tibetan Buddhist kingdom), we visit one of the most visible local landmarks: the National Memorial Chorten, a whitewashed, gold-finialed Tibetan-style stupa, or shrine, built as a memorial to Bhutan’s third druk gyalpo, the current king’s grandfather, who began opening the country to tourism. On this waning winter afternoon, with the mountains all around sharply etched, we are, incredibly, the only foreigners present. But the place is popping. A steady stream of locals of all ages, at different speeds, circumambulate the shrine. “It must be done 108 times,” Dorji explains. “One stands for you, the individual, zero is for emptiness, and eight is for the number of paths to Buddha and of titulary deities.” I’m confounded by the opacity of the explanation. All the same, the site has great beauty, its power augmented now and then by the chiming of the giant, gold-painted prayer wheels near the entrance. We spin the wheels ourselves, putting some muscle into it and hoping for who knows what.

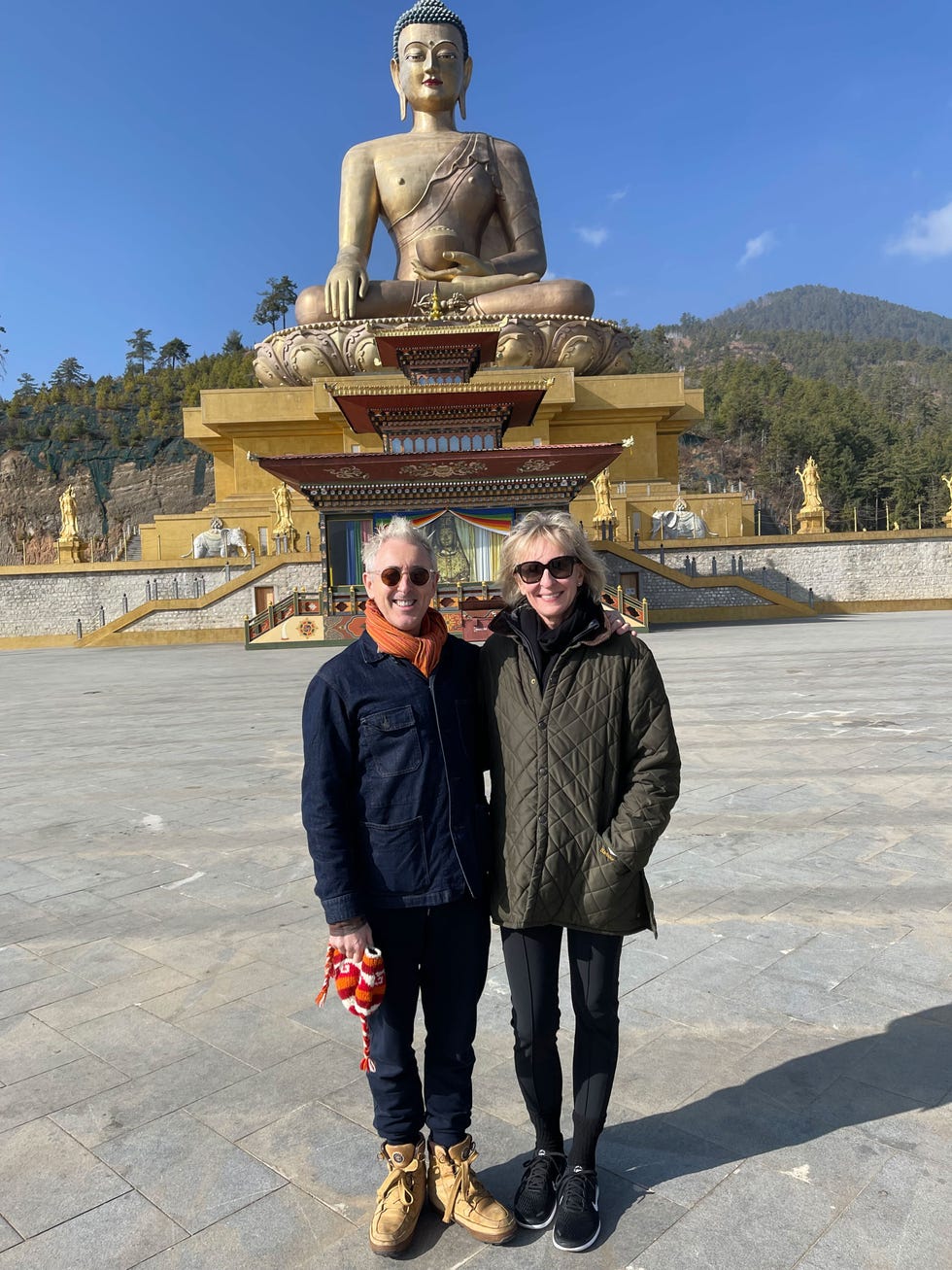

The next day offers an abundance of delightful—and even greater—confusions. Our first stop is the gilded Buddha Dordenma, which, at some 200 feet high, is the largest sitting Buddha in the world. (It was built in China, financed to the tune of $100 million, chiefly by Singaporean businessman Peter Teo, and completed in 2015.) Its location, overlooking Thimphu Valley—we are, again, alone on the immense plaza—was prophesied twice: in the 20th century by the yogi Sonam Zangpo, who said a large statue would be built in the region to bestow blessings, peace, and happiness on the whole world, and back in the 8th century by Guru Rinpoche, who is one of the most important figures in Bhutanese history, having introduced Buddhism to the country. Guru Rinpoche is also regarded as the second Buddha, Dorji tells us. He had eight different “manifestations” (like reincarnations but not quite) and assumed during each one a different appearance, personality, and name. Our heads are spinning.

I do not envy Dorji’s having to explain to a group of Westerners, who are obsessed with facts about historical figures and events, the history and traditions of a country steeped in complex Buddhist folklore and mythology, in which tales of shape-shifting demons and miracle-working saints abound, and where actual events are a messy mélange of rival Buddhist lineages, battling lamas, and warlords.

At the impressive Institute of Traditional Medicine Services, the amount of information is giddying. Established in 1968 by the fourth druk gyalpo, the current king’s father, it’s a teaching hospital that trains doctors in Sowa Rigpa, the ancient art of healing based on the teachings of Sangye Menlha, the blue-colored Medicine Buddha—an “aspect” of the historic Buddha, from the 6th century BC. Eighty-seven students are currently enrolled in the five-year degree program. A guide from the institute takes us around its museum, which displays some 300 variously efficacious plants, herbs, minerals, and animal parts. Large diagrammatic paintings of three trees offer a sort of cheat sheet for Sowa Rigpa protocols: The trees’ proliferating trunks, branches, and leaves are all labeled and correspond to specific pathologies, diagnostic methods, and treatments. “Sowa Rigpa practitioners consider the effect of treatment not only on the current lives of their patients,” we are informed, “but also on all their future lives.” Ah, yes, salubrious reincarnation. For the treatments to work, Dorji says, “you have to believe.”

Perhaps as a result of our ceaseless encounters with the uncanny, all four of us Bhutaniers feel that time is expanding. Days feel like weeks—in an enlivening way. One morning we leave Thimphu for Punakha via the 10,200-foot-high Dochu La pass, one of Bhutan’s most famous places: a sea of 108 whitewashed, gold-finialed stupas and a panoramic view, magnificent on this brilliantly clear January day, of the snow-tipped Himalayas—which we admire, and this is equally stunning, in perfect solitude. Beyond the mountains lies Tibet. Dorji points out Gangkhar Peunesum, or “White Peak of the Three Spiritual Brothers,” which, at 24,836 feet, is the tallest unclimbed mountain in the world. And it will remain that way: In 2003 the government banned all mountaineering out of respect for local spiritual beliefs.

When we reach Punakha Dzong—the second-oldest (1638) and the largest fortress/monastery in Bhutan, where its kings are crowned—the sun-filled stillness inside is calming, the pop of the monks’ red garments against the whitewashed walls is more beautiful than I could have imagined, and the canopy of a giant, Avatar-esque banyan tree in one courtyard soughs in the wind as if it were talking.

Chimi Lhakhang plunges us into Bhutan’s most delightful mystery, its confluence of spirituality and earthiness. The age-blackened stupa and small temple on a hillock near a village were built in honor of the 15th-century ascetic Lama Drukpa Kunley, also known as the Divine Madman (or, as Dorji calls him, trying to simplify things for us, “the phallus guy”). He is renowned for subduing demons and demonesses with his “Thunderbolt of Flaming Wisdom.” The Bhutanese affection for his contrarian, disruptive teachings and wine-women-and-song antics—and his acquired associations with fertility—is the reason phalluses adorn buildings across the land. We walk clockwise around the courtyard, turning prayer wheels, then venture inside. A woman is prostrated before the altar, which is adorned with bottles of wine, beer, and spirits, and what look like, well, dildos. Nearby are albums stuffed with photographs of babies and notes of gratitude from around the world.

After our sightseeing exertions, we yield with gratitude to the ministrations of Amankora, our lodge in Punakha, to which we return each evening: a firepit in the courtyard, blankets and hot water bottles for our laps, drinks in our hands, dinners in private rooms, and the haunting sounds of a yangchen (a hammered dulcimer) providing accompaniment until, hours later, we totter off to sleep. On the day of our departure for Paro, our last stop, two monks arrive at 7 a.m. to perform a cleansing and blessing. There are a golden figurine, flowers, incense, a gong, and a large book from which the senior monk reads and chants. Later they harmonize. The gong is struck. Water is sprinkled on our heads and lips, and rice thrown as the finale. We have no sense of time and have understood nothing, but it doesn’t matter.

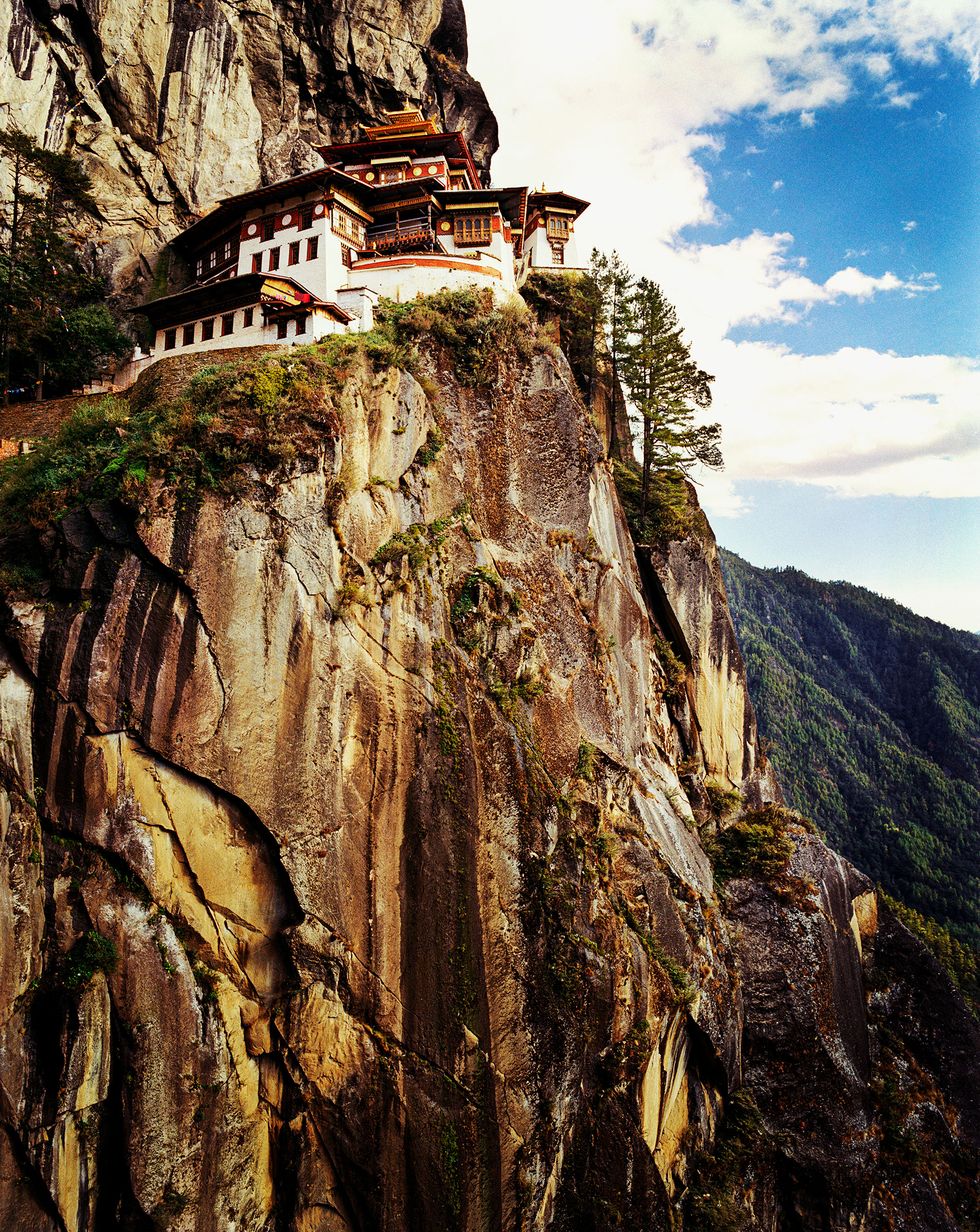

The next morning, our last day in Bhutan, the plan is to tackle the Tiger’s Nest, aka Taktshang Goemba, not only the most famous sight in the country but one of the most striking in the Himalayas, a monastery perched miraculously on the side of a sheer cliff 2,952 feet above the floor of the Paro Valley, where we are staying at the peaceful Como Uma.

Alan hasn’t slept well. Dogs, he says at breakfast, were barking all night. “Wild animals probably kept them up,” Dorji offers. “We have snow leopards up there, wild boar, even royal Bengal tigers. They move along the mountain passes.” A metamorphosis was responsible for Guru Rinpoche’s alighting in the 8th century on this rocky ledge to meditate. “He was in his eighth manifestation when he came here,” Dorji says, “in the form of Dorji Drold, or Fierce Thunderbolt. He subdued all the evil spirits hindering Buddhism, and then his consort changed into a winged tigress so he could ride up there on her back. You can do that if you practice. You can change into animals.”

“Come on, girls, we can make it,” says Alan. As we ascend to 9,678 feet through the pine forest, passed only by Bhutanese pilgrims, we notice an indentation atop a mountain and a vulture circling. “That’s a sky burial platform,” Dorji says. “It is part of our culture of giving. We sacrifice everything, even our bodies. We mostly bury babies and old people that way. They are the purest.” It takes us three and a half hours (fleet-footed Alan is hardly to blame), with rest stops, to cover the distance that Dorji says she covers in 45 minutes. Kids have birthday parties up here. We walk around nine of the 11 shrines at Taktshang Goemba, but the kaleidoscope of deities and attributes serves only to enlarge our lack of understanding. We take solace in the wisdom that, at the very least, we know what we don’t know. Before heading back down, we light butter lamps for world peace as a monk chants.

How to Book Absolutely work with a travel adviser, as there are many ways to do Bhutan. I recommend Sanjay Saxena, Sanjay@nomadicexpeditions.com.

This story appears in the Summer 2023 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

Klara Glowczewska is the Executive Travel Editor of Town & Country, covering topics related to travel specifically (places, itineraries, hotels, trends) and broadly (conservation, culture, adventure), and was previously the Editor in Chief of Conde Nast Traveler magazine.