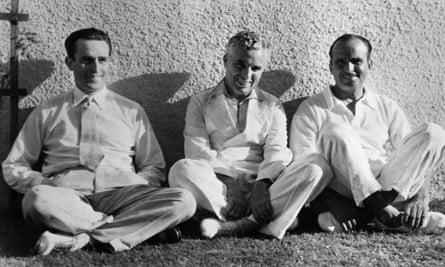

Hunky, gregarious and with a dazzling smile, Douglas Fairbanks was apparently born to be a movie star. Never lacking in ambition and enthusiasm, he also became one of Hollywood’s founding fathers. In 1919, together with his best friend Charlie Chaplin, his bride-to-be Mary Pickford, and director DW Griffith, he started the United Artists studio, which is still, despite some recent uncertainties, a Hollywood player.

In 1927, Fairbanks was a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. As the host of its first prizegiving ceremony in 1929, he handed out 14 awards to his peers, though he was never to receive an Oscar in his lifetime. In 1929, he was involved in the establishment of the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California – one of the first film studies faculties – and gave its opening lecture, on “photoplay appreciation”.

Today, film studies courses are unlikely to linger on Fairbanks’s work: it’s considered generic Hollywood product, with little more to it than dazzles the eye. That’s a shame, because the man and his photoplays were anything but ordinary. A new biography, doggedly researched and sharply written by Tracey Goessel, The First King of Hollywood: The Life of Douglas Fairbanks gives us a chance to consider the star in a new light, not least because it persistently interrogates much of his own myth-making. Discarding Fairbanks’s own merry tales, Goessel straightens out the facts about his education and early career, details the injuries caused by his daredevil stuntwork and, with reference to the blizzard of messages sent between husband and wife, gives an intimate and moving account of his marriage to Pickford.

For example, Goessel shows that Fairbanks demonstrated markedly progressive attitudes to race. In other films of the era, offensive racial terms and characterisations are depressingly familiar, but Fairbanks scoured his scripts (notably, those otherwise witty intertitles penned by Anita Loos) for all such terms before production began. Revealingly, Fairbanks never chose to make public the fact that his father, H Charles Ullman, was Jewish, constructing a smokescreen figure called “John Fairbanks” instead; this name even appeared on Fairbanks’s death certificate.

It was impossible not to notice that Fairbanks was devoted to fresh air and exercise: his athleticism on screen and deep tan attest to it. But while he was more than comfortable with public nudity, his Hollywood neighbours were not. Goessel reveals that when he and Pickford built their studio complex in the early 1920s, complete with a fully fitted gymnasium, exercise yard and steam room, Fairbanks requested an underground running track, so he could jog, naked, between scenes. The concrete-lined trench ran parallel to Santa Monica Boulevard for about two blocks, but six feet below the road. It’s a typical Fairbanks solution: breezily practical, but undeniably eccentric.

The most delicious discovery in this book is that Fairbanks’s first film was not his starring role in 1915’s The Lamb, but a remnant of his stage career – and it’s in colour, too. Sadly, the 1913 actuality short, showing the stars of a Broadway production called The New Henrietta relaxing off-stage, is considered a lost film, but the thought of seeing Fairbanks the stage actor on film, and in an early form of colour (Kinemacolor, devised by GA Smith of Brighton), is a tantalising one. It’s notable that when Fairbanks made a two-strip Technicolor blockbuster in the 1920s (The Black Pirate), the palette was deliberately muted, to avoid the sugary over-saturation of many early attempts at colour reproduction. Perhaps his first glimpse of his own face on film was especially unnerving.

Douglas Fairbanks died relatively young, aged 56, in 1939. He was reconciled with his actor son Douglas Fairbanks Jr, but divorced from Pickford and hastily remarried to English socialite Sylvia Ashley. During his career, he made many wildly popular and influential films, and left an indelible mark on the industry he championed. If he is not given his due today, perhaps it was his own fault. He made all his feats, from storytelling to stunts to managing a studio, look far too easy – and more like fun than work.

In celebration of the great man, here are five unmissable Douglas Fairbanks movies.

The Good Bad Man (Allan Dwan, 1916)

This pacey western from Fairbanks’s early years is, like the actor himself, deceptively straightforward. It is also the first film in which the star had a say in the storyline, sketching a plot that a scenarist would develop into a script, and working out the action sequences on set. Fairbanks plays Passin’ Through, a flashy outlaw who steals with impunity and distributes the loot to orphaned children. There’s a reason for his generosity: despite his swagger, Passin’ Through has doubts about his own parentage, which gives him an affinity with fatherless children.

These were doubts that Fairbanks shared – his mother had been married twice before meeting his father, who left the family when Fairbanks was a boy. In fact, his parents’ marriage was a bigamous one, as Fairbanks’s father had not been divorced from his first wife. He had died the year before Fairbanks made this otherwise zippy film, which subtly reflects his anxieties.

The critics delighted at seeing Fairbanks in a western, and praised the film for its originality. The New York Dramatic Mirror said: “We cannot remember ever having seen a photoplay just exactly like it.”

When the Clouds Roll By (Victor Fleming, 1919)

Loopy and lovable, When the Clouds Roll By has a premise that is as bizarre as it is unpleasant. Fairbanks plays Daniel, a superstitious, monied young man who unwittingly becomes the subject of a scientist’s sick experiment. Dr Ulrich Metz (Herbert Grimwood) intends to provoke such mental distress in Daniel that he will be driven to suicide. The first shot he fires is an indigestible meal (“Our tale proper begins with the eating of an onion”), which prompts a brilliantly inventive nightmare sequence, with Fairbanks chased by giant vegetables, walking on the ceiling (thanks to a revolving room and camera) and entering a posh party wearing saggy pyjamas. Despite Victor Fleming’s director credit, Goessel reveals that this sequence cannot be attributed to the man who made The Wizard of Oz (1939) – it was actually shot and discarded by Joseph Henabery, a frequent Fairbanks collaborator, for an earlier film, His Majesty the American (1919).

The showstopping final reel is classic Fairbanks, and Fleming, though: a flood scene that uses more than a million gallons of water, and ends with a wedding on top of a floating chapel roof. This was Fairbanks’s first big hit in his United Artists career, after the disappointing returns of His Majesty the American, sans galloping carrots.

The Mark of Zorro (Fred Niblo, 1920)

Possibly Fairbanks’s most famous role, his first out-and-out swashbuckler, and certainly his most stylish. This gleaming California caper features Fairbanks as a sort of forerunner to comic-book superheroes: his Bruce Wayne is a dopey toff named Don Diego, who becomes, once kitted out in cape and boots, Zorro, a cheeky, sexy rogue who slashes a “Z” into the flesh of his victims. Fairbanks’s triumph here is to give his all to both sides of the coin – Diego gets the laughs as a dork obsessed with duff magic tricks, and Zorro is a showcase for the actor’s boundless energy and fearless stuntwork.

Repeatedly remade and homaged (Shrek’s Puss in Boots is a Zorro clone who carves a “P” instead of a “Z”, and has a second spinoff film in production), it’s a classic of the silent era, with a snippet of its climactic chase scene stitched into The Artist (2011). It’s now amusing to remember that The Mark of Zorro was based not on an esteemed book but a pulp magazine story, The Curse of Capistrano, that Pickford had to bargain with her husband to read. He hated to sit down to a book, so she took advantage of a long train journey and promised Fairbanks two card games if he would only read the darn thing, rightly convinced it would be the perfect vehicle for her husband.

Robin Hood (Allan Dwan, 1922)

Goessel tackles another Fairbanks myth when she discusses this comic caper. No, Fairbanks did not take one look at the giant castle set and back away from the project for fear of being upstaged by the scenery. He was amazed when he saw the castle, certainly, but immediately rushed in to inspect the detail, and improvise ideas within its walls, including the gruesome murder of Guy of Gisborne. “Look,” he told publicist Robert Florey, “his body goes round the pillar; with one arm I hold his throat, with the other his heels, and I slowly break his back.” And that’s just how the scene plays in the film, although inevitably the censors took exception, and their scissors, to the “inhuman” kill scene, giving it a little trim. For all that, Robin Hood remains a family favourite, as springheeled as its exuberant star.

The Thief of Bagdad (Raoul Walsh, 1924)

Remembered as much for its extravagant, shimmering sets designed by William Cameron Menzies and its fanciful special effects as its lead performance, The Thief of Bagdad is a testament to Fairbanks’s ambitions, and his wholesome values. The film’s motto, “Happiness must be earned”, could have been Fairbanks’s own. Here he plays the title role of Ahmed, a street robber who falls in love with a princess and undertakes mighty challenges to win her love and save the city from invaders.

Fairbanks is buoyant in this film, giving a supple performance that is as much dancing as acting, with slinky movements and broad gestures. And despite the fact that he was well into his 40s, he is every inch the action hero, stripped to the waist, trampolining in and out of urns, and soaring through the air on a magic carpet. The Arabian Nights material dates badly, but this, one of the era’s most expensive films, may well be Fairbanks’s masterpiece, best appreciated on a big screen, through the mist of adoration that his fans felt for him in the 1920s.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion