Nine women converge at a table. Most are wearing black, their bodies disappearing into the intimacy of friendship, of a figureless shape. One is sipping tea, and another is smoking a cigarette. Behind them, a tawny-brown curtain is half-drawn and falls floor to ceiling. Adjacent to it, four paintings hang arbitrarily on a wall. One is a portrait of Disney’s Snow White, and another a geisha in profile. There is of course more to catalogue – a jug of water, some cups, the arm of a chair, the square of skin between a woman’s pant leg and her sock, the way one woman’s hands fold over each other in repose or unrest, it’s unclear. These are the kinds of observations Swedish artist Karin Mamma Andersson’s paintings prompt because her work is a study – albeit blurred, oftentimes crepuscular and doll-like in ratio and tone – of the everyday.

Things, stuff, domestic goods, the way we slouch, the way we sleep and the arcane quality of interior life: these are just some of the concerns that people Andersson’s work for her show Behind the Curtain, now on view at David Zwirner. It’s worth noting that in the painting described above, About a Girl (2005), only three of the women are staring at us, the viewers, as if this painting was a photograph (or film still) taken surreptitiously by a 10th woman: us. Time and again, Andersson’s work yields a near-hypnotic sense of familiarity, the kind born of found photographs of strangers: the obscured meeting of privacy and inclusion, but scaled disproportionately to one’s misremembered childhood perceptions of what was big and what was small.

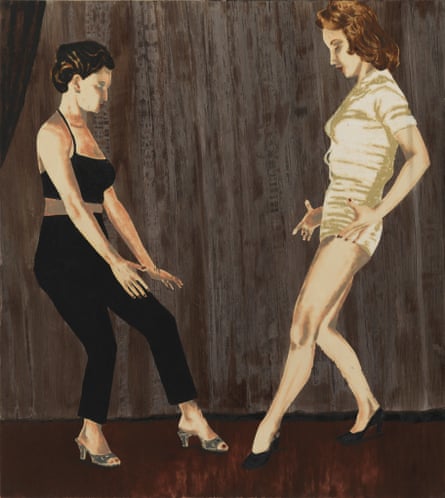

Andersson, who was born in Sweden and who studied and still works at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Stockholm, creates worlds that, despite their prosaic themes, are imbued with a Nordic appraisal of limited daylight, of folklore, of macabre landscapes with zero traces of modern life – no phones, no screens, no laptop light. Staring at her work, one half-expects to hear a kettle rattling and whistling on a stove before ever hearing, say, a phone beeping. Swapping between thick brushstrokes and a watery-stained palette of cream, beige, deep navy, brown and rusty pinks, Andersson’s painting are often spooked by black splotches or what appear to be the curled browning and blackening of burnt paper. Inner life is, as perceived by Andersson, ominous and even a bit artificial – some rooms mimic the dioramic detail of theater set design. Andersson illustrates the ways in which we remain remote to those nearest to us, and especially to ourselves.

Like the writer Lydia Davis’s hauntingly brief accounts of domestic tensions, Andersson’s work juxtaposes play with Poe-like suspense, exemplified by titles like Tick-Tock and We Work So Closely Without Even Knowing It. Occasionally inspired by crime scenes, some of Andersson’s pieces are narratives in media res: objects left behind in a hurry, a cinched tablecloth, tossed clothes, emptied drawers and the discomforting sense of once-was mere moments ago.

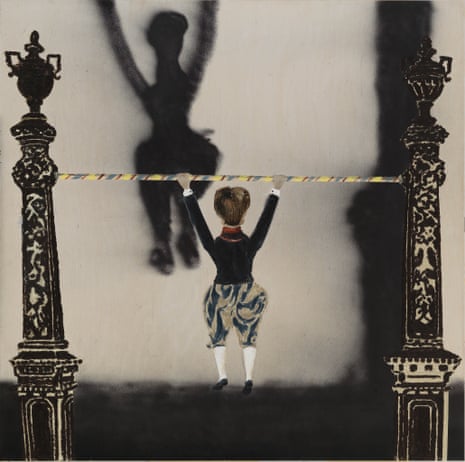

But what also underpins Andersson’s work and is ever-present in her most recent show is the eerie potency of the miniature. Think: the offish yet nostalgic nature of one’s childhood music box or how toys, as recalled in Andersson’s Hangman – a marionette’s colossal shadow as it swings from a wire – portend something far darker and spectral despite their intended novelty. Like a curio cabinet’s collection of knick-knacks and doodads that as a result of being stuck in time are wistfully foreboding. It’s this very layering of rich detail with wooden paper doll-like figures that evokes Andersson’s re-imagining of memory, of its scope and fictive capacity.

- Mamma Andersson: Behind the Curtain is at David Zwirner, New York, until 14 February.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion