Whenever I have been to the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona – and I have visited Josep Lluís Sert's lovely building on Montjuïc many times over the last quarter-century – I try to see Miró's great 1968 triptych Painting on White Background for the Cell of a Recluse. It isn't always on display. There's nothing much to the three white canvases. No colour, no forms. Each enormous canvas is painted with a single black line over an unevenly primed white ground. You can tell where the slender brush has run out of paint, is recharged, then continues on its way with the same unknowable purpose, like the passage of an ant or a bird in flight, or the journey the eye makes along a horizon. Or like a long hair lost in the bedsheets, a memory of something or someone.

The recluse of the title might be the artist himself, painting one afternoon with the shutters closed against the brightness of the day in his studio on the island of Mallorca, during the month that the students rioted in Paris and General Franco still ruled Spain. It is a daft idea, to paint just a skinny wandering line across such a big canvas. How could it possibly work? But it does. There is a palpable difference between a line that's alive and tense and somehow natural, and one that dies like a bum note. You can feel the vitality of Miró's line from your head to your toes, your hand clenching and unclenching in your pocket, somehow feeling in your own body the artist's concentration – the tensing of his wrist, the movement of his hand – as you follow the line on its way to nowhere. I imagine Miró holding his breath as he draws, and I hold mine too as I look.

This work, along with three other late, large triptychs, is now being shown in two beautifully installed octagonal rooms towards the end of a new retrospective at Tate Modern. Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape brings us his art not just in its most characteristic guises – playful, childlike, direct – but attempts to bring out Miró the "international Catalan" and internal exile in Franco's Spain; Miró the political artist; and the avant-garde surrealist and modernist who wanted – so he once said – to assassinate painting.

Miró never did succeed in killing painting, that walking corpse that still refuses to lie down and take it quietly. He had a brush in his hand, not a stake. He also wanted his art to be useful. In 1979, four years after Franco's death, he said in a speech at Barcelona University that "being able to say something, when the majority of people do not have the option of expressing themselves, obliges this voice to be in some way prophetic … When an artist speaks in an environment in which freedom is difficult, he must turn each of his works into a negation of the negations, in an untying of all oppressions, all prejudices, and all the false established values."

Nowadays this sort of talk sounds a bit quaint. We have almost lost our faith in the redemptive powers of art. In Spain's newly emerging democracy, Miró's art felt symbolic, both of resistance to Franco's state and of the new freedoms that were coming into being. With the best of his work, I too feel genuinely lifted, transported, energised, though I just feel deadened looking at his murals and public sculptures, the endless prints, that overly jolly logo he devised for the La Caixa savings bank.

Whatever formal and sometimes theatrical murders Miró perpetrated on his art – at one point dousing paintings in kerosene and setting fire to them, just like Yves Klein - you feel Miró's heart wasn't entirely in it. He could never escape his wit and energy and ribaldry, though at times this was mixed with a profound anger. In his long Barcelona series of lithographs, conceived around 1940 but only printed in 1944, Miró depicts buffoonish, highly sexualised but impotent ogres menacing innocents across a suite of 50 prints. They're based on playwright Alfred Jarry's cowardly dictator Pére Ubu as much as Franco and his generals.

A series of copper panels from 1936 sees exquisitely nasty, lurid figures squirm and gesticulate, show off their sex organs and pontificate in arid landscapes (in one case, in front of a pile of excrement), filled with disgust and a loathsome sexuality. Later, in the 1973 triptych The Hope of a Condemned Man, Miró alluded to the execution of the young Catalan anarchist Salvador Puig Antich, garrotted in prison that same year. The three-part painting is dominated by a line that sighs and falls with faltering resignation, percussive scribbles of colour like memories about to pass, and a thin rain of flicked paint. One cannot but think of the artist contemplating his own passing, though he was to live on until Christmas Day 1983, dying at 90, having seen the first socialist government come into power since the civil war.

Breasts, balls and tongues

Miró was never cut out to be a total iconoclast, and in his art the ghosts of Jan Brueghel, Hieronymus Bosch and the anonymous masters of the Romanesque frescoes that once decorated churches through the Catalan Pyrenees, collide with his fertile imagination. They make themselves felt alongside the influences of his friends Picasso and Masson, and works by Gorky, Rothko and Pollock he encountered in his trips to New York in the late 1940s and 50s.

Influence is one thing. What Miró found in his forebears and contemporaries, as much as in the world about him, were formal openings and opportunities, mental spaces as much as physical forms, that he could inhabit. Miró was always Miró. Whether he was painting donkeys and vegetable patches and a carob tree, in paintings as detailed as The Farm (bought by Ernest Hemingway), or in paintings as emptied-out as his schematic portraits of Catalan peasants, or his triptychs and late abstractions, the drive is all his own.

There's just too much life in his art, even if it is sometimes of an alarming sort. Here, even emptiness pulses with energy. Paul Klee famously talked of taking a line for a walk. Miró could draw a line across galaxies or from the breast to the hip; along an entire horizon or into an all-engulfing void. Sexual energy pulses through his work, along with scatological Catalan humour and earthiness, a love of nature, and nostalgia for the rural life.

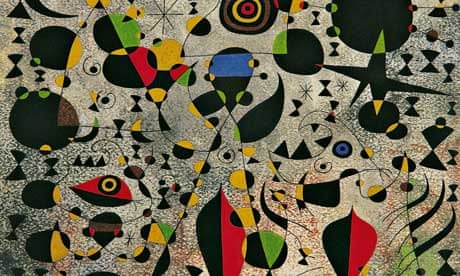

Miró's art was colourful and dirty, life-affirming and nasty, musical and jarring, lyrical and ejaculatory and excremental. There are penises and vulvas, assholes and pubic hair, breasts and balls, lips and eyes and tongues everywhere, even in the 1940-41 Constellations series, which jangles with heads and stars, birds and bullseyes, monsters, fish, a bestiary of madness and teeming thoughts, all related in some strange and almost astrological way to war, and to Johann Sebastian Bach. How at once lovely and unsettling these paintings are; they rock the mind as well as the eye.

Refusing the official stamp

Miró kept the paradoxes going. He insisted on his Catalan name – Joan not Juan – but titled his works in French. His art – and he would insist his soul – was rooted in Catalonia, but also in surrealism, and in postwar American painting. He continued to live in Mallorca, and show internationally, while refusing the honours of Franco's government or to participate as an official Spanish artist in biennales, sabotaging almost all attempts to get him to do so. Unlike Dalí, he made few accommodations to the state, just as he had earlier refused to become a social realist or a communist, or to toe the surrealist line. This is why Miró became so important a figure for a younger generation of Catalan artists, like Antoni Tàpies and the visual poet and playwright Joan Brossa.

Hardly any retrospectives are complete. There is always something missing – either absent works or the artist's spirit, which can easily be destroyed by bad curatorship. The last big Miró retrospective I saw, in New York in 1987, missed so much of the Miró present here, a deeply complex artist, political and playful, full of sex and spirit, earth and sky.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion