Despite What You May Think, Haggis Does Not Have Scottish Origins

Haggis, though a symbol of Scotland's national pride alongside tartan and whiskey, has a multinational lore of indeterminate origin. Food writer Alan Davidson describes haggis in the "Oxford Companion to Food" as "the archetype of a group of dishes, which have an ancient history and a wide distribution," suggesting the recipe was shared across cultures as a means of meat preservation.

Beyond the humble ingredients and savory flavor championed by the Scots, haggis has an international heritage, being a versatile dish that once served a purpose as practical as it is patriotic today. Without much historical record to suggest otherwise, the Scottish adoption of haggis is fairly recent history compared to other cultures that have been cooking up a similar dish for millennia. The exact origin of haggis is consequently somewhat mythical, but it has become so entrenched in Scotland's sense of individuality that this fierce love for the dish makes it an uncontested aspect of Scottish identity.

As a recipe made from offal (internal organs), there's a preconception west of the Atlantic that haggis must be awful. This amalgamation of innards from various game animals (which traditionally includes sheep lung) has been illegal in the U.S. since 1971 when the U.S. Department of Agriculture deemed lungs unfit for human consumption as a matter of food safety. Though lung-free, USDA-approved haggis does exist stateside, Scots in the U.S. have had to resort to smuggling in order to import the truly authentic variety (just ask Sam Heughan).

Is haggis a sausage or a pudding?

Haggis is made similarly to sausage, with chopped meat sealed inside animal innards; once cut open, it resembles crumbled sausage in both texture and appearance. But officially, haggis is considered a pudding. British pudding has a much broader definition than the American assumption that this must be something both custardy and sweet. British puddings can also be savory, and consist of anything that is cooked by being steamed or boiled in something else (including animal intestines).

No matter how it is categorized, haggis can be made from any kind of meat, though traditionally sheep pluck is used – aka offal. This comprises the liver, heart, and lungs, which are cooked, minced, and mixed with suet, oatmeal, and seasonings, then stuffed into the sheep's stomach, which gets stitched up to hold everything in, and then boiled for a few hours. The final result — a blob of savory goodness — gets sliced open and served with neeps and tatties (mashed turnips and potatoes).

Haggis has a nutty texture and peppery flavor. It can be eaten à la carte and also makes for a delicious sandwich filling (haggis piece), piquant stuffing, or highly flavorful meatballs.

What haggis is NOT

While haggis may be vaguely defined in that it can be made from many kinds of meat, there is a misconception that the name refers to a mythical living creature. The Scots, who have long been partial to perpetuating their own mythologies, have spread rumors of the "wild haggis," a creature as elusive as the Loch Ness Monster that is purported to be the source of the titular dish.

This "Haggis scoticus," a wee beastie somewhere between a hedgehog, a rodent, and a long-haired guinea pig, is said to roam the highland hillsides. While the origins of this myth remain untraceable, it may have gained traction in the 1920s when satirist and journalist James. J. Montague described a hunt for this dangerous Caledonian creature in a 1924 issue of the New York Tribune (via Atlas Obscura). Whether this was the catalyst or not, Americans have certainly succumbed to the lore. A 2003 poll (via The Guardian) of 1,000 U.S. tourists in Scotland revealed that one-third believed haggis was a wild animal, and the majority of these came to Scotland thinking they would catch one.

While the wild haggis may not be real, the hunt certainly is. Though anyone can partake in a haggis hunt, the odds of catching one are greatly increased by joining forces with a gillie (a haggis hunter who knows the terrain). The humorous folklore surrounding these fictitious creatures suggests that the traditional hunting season runs from the end of November through January, between St. Andrew's Day and Burns Night.

The ancient origins of haggis

Alan Davidson also states that a precursor to haggis dates back to ancient Rome. Cooking animal innards was not an uncommon practice among Roman foot soldiers, who needed a method of preserving the meat they caught to take on long marches. When butchering meat on the move, the offal would not keep unless cooked immediately or preserved. Wrapped in the animal's stomach and boiled, it could last for weeks.

The ancient Greeks also had claim to this form of edible lunchbox, which is referenced in Homer's "Odyssey." Odysseus encounters an antediluvian haggis prepared by "a man before a great blazing fire turning swiftly this way and that a stomach full of fat and blood, very eager to have it roasted quickly." There isn't much evidence to suggest this culinary phenomenon was necessarily Greek before it was Roman, but Rome did absorb Greece into its empire, and many aspects of Greek culture along with it.

The British could likely have inherited the recipe for haggis when Brittania joined the Roman Empire with the invasion of Emperor Claudius in AD 43. Roman soldiers overtaking the British Isles would have brought their transitory cooking habits with them. While Alan Davidson notes that haggis could be an adaptation of the Romans' recipe to utilize the local mutton and oats, he also concedes that "the Scottish haggis may be an entirely indigenous invention, but in the absence of written records there is no way of knowing."

A link to the Vikings

Though cultural invasion might speak to haggis's possible Latin or Hellenic origins, the Romans were not the only people to conquer the British Isles. Similar evidence suggests that haggis could have been adopted from Norse culture instead, following the invasion of the Vikings a few centuries later when they colonized the Orkney and Shetland islands. This led to an even more direct influence over Scottish lands than the Romans, who settled predominantly in England and Wales.

To further the Nordic origin story, haggis bears a remarkable resemblance to the Scandinavian dish lungmos ("mashed lungs"). This hearty Viking fare was also often made from sheep offal and packed into the stomach for easy transport, a vessel called a "Baggi" (which fittingly translates to "bag" or "parcel"). Considering the phonetic similarities between Haggis and Baggi, the alleged Norse origin has both a linguistic and a culinary backing. The only discernible difference between the two dishes is that the offal in lungmos is mixed with barley, as opposed to the oats in traditional Scottish haggis, which could simply be another example of a recipe adapted to accommodate local resources.

There's also another origin theory of Viking linguistics. Walter Skeat, a Victorian philologist, discerned that the "hag" in haggis likely came from either the Old Norse verb "haggw," or the Old Icelandic verb "hoggva," which both mean "to chop," an apt description for what goes into making the dish.

The auld French connection

France is yet another nation whose culture once had influence over Scottish taste. This began when the Auld Alliance was signed at the end of the 13th century, banding the two kingdoms together to prevent further English expansion.

This bond strengthened after France turned to Scotland for aid following a devastating defeat during the Battle of Agincourt. The Scots went on to ensure many more French victories, including Joan of Arc's relief of Orleans during the Hundred Years War. Though this partnership was officially militaristic, it was especially convivial due to the Scots' love of French wine. Considering this fraternity enabled France and Scotland to share military and culinary resources for nearly 300 years, it is not surprising that a French taste might remain in the Scottish tongue — scholars subsequently credit a French influence to haggis's name. The New York Times suggests the word is derivative of the French "hacher," which means to "chop up" or "mangle."

The French also have a dish somewhat similar to haggis. Their tripes à la mode de Caen hails from Normandy, a hearty stew of cow stomach, hooves, and bone. This dish is attributed to Sidoine Benoit, a monk who lived in Caen during the 14th century, a timeframe that does coincide with the beginning of the Auld Alliance. But Normandy is so named after the Normans who conquered this part of France, which might, through the transitive property, add another point in favor of haggis' Viking origins.

Other nations have versions of haggis

A comparison of carnivorous national dishes indicates that haggis could very likely be a culinary phenomenon that many cultures developed independently. Chireta is a dish from the Spanish Pyrenees that also uses sheep offal, though this Spanish take mixes the meat with rice and seasons it with cinnamon, garlic, paprika, and parsley. Drob is a Romanian dish traditionally served at Easter that uses lamb offal. Though the final result is more like meatloaf, the traditional recipe stuffs the meat into a sheep caul, serving the same purpose as the stomach does to hold haggis together. Sweden's pölsa resembles the Norse lungmos that may have been the haggis predecessor, though it is usually made from beef or pork.

Haggis appears not to be specific to Europe, either. The Native American dish pemmican is made from meats combined with fat and berries, then stuffed into a bag made from animal hide or stomach. This nutrient-rich food keeps for years and functioned as essential nourishment during harsh winters. It was adopted later by the British Royal Navy to provision Arctic expeditions.

A case for English roots

The primary evidence for haggis's possible English origins is that the first written record of a recipe is in English. One of King Richard II's cooks, Afronchemolye, recorded a recipe in 1390 that features a seasoned mixture of eggs, breadcrumbs, and sheep's fat that was boiled in the sheep stomach.

Food historian Catherine Brown further emphasized the English claim to this culinary mystery in discovering another reference to a haggis recipe that predates any written Scottish claim to the dish. In an interview with the BBC, she explained that this recipe comes from a popular housekeeping guidebook from 1615 by Gervase Markham, "The English Huswife," which was full of tips for recipes and remedies, and was probably a good resource for compiling English grocery lists in the 1600s.

Though this written evidence proves that the English once cooked and enjoyed haggis with some regularity, it does not prove that the English did in fact invent it. Instead, it could be a testament to the enthusiastic English adoption of the recipe from their Roman invaders. The English may, however, be solely responsible for one creative adaptation — a 15th-century recipe for porpoise haggis was considered a luxury among England's medieval feasts, combining porpoise blood and grease, oatmeal, and seasonings that were cooked in the porpoise stomach.

The rise of haggis with economic decline

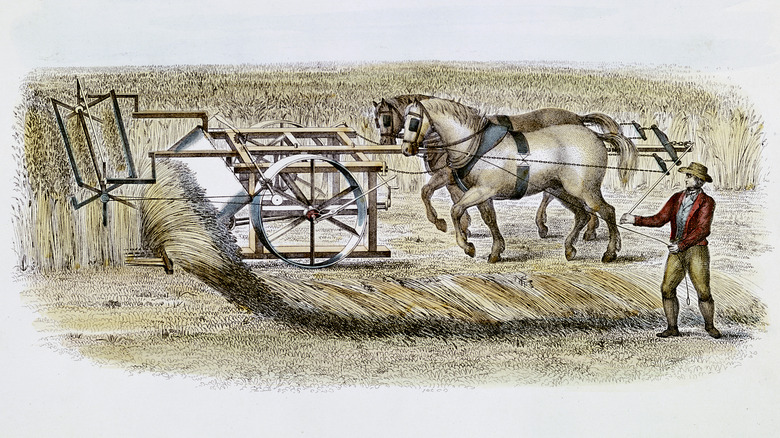

Whether or not haggis was a staple in England before it reached Scotland, technological innovations brought about its decline in English popularity. The Agricultural Revolution in Britain, which took off during the 18th century, brought about a major increase in agricultural production. New developments in farming machinery created more efficient harvesting, and the adoption of crop rotation made for more bountiful soil. This increase in productivity remedied the food shortages and financial hardship that had plagued many pre-industrial English farmers. Suddenly, more people could afford better cuts of meat than the offal that poorer demographics had previously relied upon.

Conversely, at the end of the 17th century, Scotland faced subsequent years of failed harvests. This famine, known as the "Seven Ill Years," led to the loss of 15% of the Scottish population. Mass starvation was coupled with economic decline and a power imbalance that came with the Act of the Union with England in 1707, which united England and Scotland under the name of The United Kingdom of Great Britain. While this union helped revive Scotland's farming economy with the introduction of improved technology and techniques, this commercialization of agriculture displaced many poor tenant farmers, who could no longer afford their rents. Haggis became a nourishing way that Scotland's expanding poorer classes could feed themselves affordably, as it was made from inexpensive ingredients and the cuts of meat that others no longer wanted.

A dish peppered with politics

History marks another clear turning point for the Scots claiming haggis as their own. Shortly following the union of England and Scotland, a spirit of revolt simmered with the Jacobite Risings, and then the Jacobite Rebellion, a series of failed attempts by the Scots to help deposed King James reclaim his throne. Though this rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, the English remained resentful towards their revolting neighbors, and began to disdain the Scots with an air of superiority. Besides caricaturing them as barbarians, the English derided the widespread poverty of Scottish people, particularly the poor man's fare they consumed. Samuel Johnson offered a particularly biased perspective of this anti-Scottish sentiment in his "Dictionary of the English Language," first published in 1755. In one entry, he defined oats as "a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people."

Haggis also fell victim to this nose raising, and the English no longer wanted any association with the dish. In defiance of this scorn, the Scots made a point of claiming haggis as a means of further differentiating themselves from the English. A passion for this dish, which came to represent Scottish stoicism, nullified Scotland's wounded pride by proudly distinguishing its palate. Catherine Brown summarized for the BBC that the dish "was popular in England until the middle of the 18th century. Whatever happened in that period, the English decided they didn't like it and the Scots decided they did."

Literature claimed haggis for Scotland

Part and parcel of this Scottish love for something the English came to regard with distaste was Robert Burns' contribution to Scotland's defiant favor of haggis. Burns (perhaps best known for his poem "Auld Lang Syne") would go on to become Scotland's national poet. His 1786 poem "Address to a Haggis," though slightly satirical in tone, is what put this dish on the Scottish map as a source of true national pride.

Burns' legacy was formally honored when England's George IV visited Scotland in 1822 in an attempt to bridge the unfriendly divide that had grown between the two nations. The king's visit prompted a novelty demand for Scottish culture, and was the catalyst for increased popularity in making a tradition of Burns' Night, which has since become an annual holiday to celebrate the poet's birthday on January 25th. A traditional Burns Night entails a hearty supper of Scottish fare, of which haggis is the pièce de résistance. Bagpipes herald the haggis as it is brought into the dining room, and the dinner's host recites Burns' "Address to a Haggis," then ceremoniously slices the main course. Everyone toasts the "Great Chieftan 'o the pudding race" and washes down the haggis feast with plenty of whiskey.