Auschwitz Is Not a Metaphor

The new exhibition at the Museum of Jewish Heritage gets everything right—and fixes nothing.

The week I bought my advance timed-entry tickets for “Auschwitz: Not Long Ago, Not Far Away,” the massive blockbuster exhibition that opened in May at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in downtown Manhattan, there was a swastika drawn on a desk in my children’s public middle school. It was not a big deal. The school did everything right: It informed parents; teachers talked to kids; they held an already scheduled assembly with a Holocaust survivor. Within the next few months, the public middle school in the adjacent town had six swastikas. That school also did everything right. Six swastikas were also not a big deal.

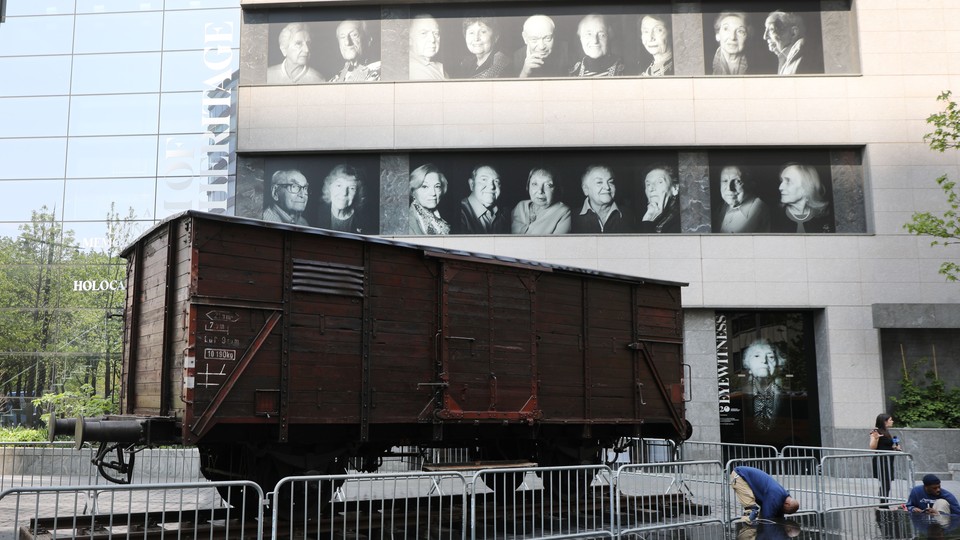

“Auschwitz: Not Long Ago, Not Far Away” is a big deal. It is such a big deal that the Museum of Jewish Heritage had to alter its floor plan to accommodate it, making room for large-scale displays such as a reconstructed barracks. Outside the museum’s front door, there is a cattle car parked on the sidewalk; online, you can watch video footage showing how it was placed there by a crane. The exhibition received massive news coverage, including segments on network TV. When I arrived before the museum opened, the line for ticket holders was already snaking out the door. In front of the cattle car, a jogger was talking loudly on a cellphone about pet sitters.

When I was 15 years old, I went to the Auschwitz-Birkenau site museum in Poland. I was there with March of the Living, a program that brings thousands of Jewish teenagers from around the world to these sites of destruction. It is the sort of trip that clever people can easily critique. But I was 15 and already deeply invested in Jewish life (I later earned a doctorate in Yiddish and Hebrew literature, subjects I teach today), and I found it profoundly moving. Being in these places with thousands of Jewish teenagers felt like a thundering announcement of the Holocaust’s failure to eradicate children like me.

This was in the 1990s, when Holocaust museums and exhibitions were opening all over the United States, including the monumental United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Going to those new exhibitions then was predictably wrenching, but there was also something hopeful about them. Sponsored almost entirely by Jewish philanthropists and nonprofit groups, these museums were imbued with a kind of optimism, a bedrock assumption that they were, for lack of a better word, effective. The idea was that people would come to these museums and learn what the world had done to the Jews, where hatred can lead. They would then stop hating Jews.

It wasn’t a ridiculous idea, but it seems to have been proved wrong. A generation later, anti-Semitism is once again the new punk rock, and it is hard to go to these museums in 2019 without feeling that something profound has shifted.

In this newest Auschwitz exhibition, something has. The New York display originated not from Jews trying to underwrite a better future, but from a corporation called Musealia, a for-profit Spanish company whose business is blockbuster museum shows. Musealia’s best-known show is the internationally successful “Human Bodies: The Exhibition,” which consisted of cross-sectioned, colorfully dyed cadavers (sourced, it was later revealed, from the Chinese government) that aimed to teach visitors about anatomy and science. Its other wildly popular show is about the Titanic. This is, of course, not a disaster-porn company but rather an educational company—and who could argue against education?

Perhaps the earlier Holocaust museums built by the Jewish community were unsuccessful simply because of their limited reach; despite the 2 million annual visitors to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, two-thirds of Millennials in one recent poll were unable to identify what Auschwitz was. Six hundred thousand people saw Musealia’s Auschwitz exhibition during its six months in Madrid before it arrived in New York. Those 600,000 people have all now heard of Auschwitz. There is clearly public demand.

And the Musealia people clearly know what they are doing. The Auschwitz exhibition was produced in cooperation with numerous museums, most prominently the Auschwitz site museum in Poland, and was carefully curated by diligent historians who are world-renowned experts in this horrific field. It shows.

The Auschwitz exhibition is everything an Auschwitz exhibition should be. It is thorough, professional, tasteful, engaging, comprehensive, clear. It displays more than 700 original artifacts from the Auschwitz site museum and collections around the world. It corrects every annoying minor flaw in every other Holocaust exhibition I have ever seen. It does absolutely everything right. And it made me never want to go to another one of these exhibitions ever again.

The exhibition checks all the boxes. There are wall texts and artifacts explaining what Judaism is. Half a room describes premodern anti-Semitism. There are sections on the persecuted Roma, homosexuals, the disabled; the exhibition also carefully notes that 90 percent of those murdered in killing centers like Auschwitz were Jews. There are home movies of Jews before the war, including both religious and secular people. There are video testimonies from survivors.

The exhibition is dependable. There is a room about the First World War’s devastation, and another on the rise of Nazism. The audio guide says thoughtful things about bystanders and complicity. There are cartoons and children’s picture books showing Jews with hooked noses and bags of money, images familiar today to anyone who has been Jewish on Twitter. There are photos of signs reading Kauft nicht bei Juden, Don’t Buy from Jews, a sentiment familiar today to anyone who has been Jewish on a college campus with a boycott-Israel campaign. There is a section about the refusal of the world to take in Jewish refugees. Somewhere there is a Torah scroll.

The exhibition is relentless. After an hour and a half, I marveled that I was barely past Kristallnacht. What the hell is taking so long? I found myself thinking, alarmed by how annoyed I was. Can’t they invade Poland already? Kill us all and get it over with! It took another hour’s worth of audio guide before I made it to the Auschwitz selection ramp, where bewildered Jews were unloaded from cattle cars and separated into those who would die immediately and those who would die in a few more weeks.

Somehow after I got through the gas chambers, there was still, impossibly, another hour left. (How can there still be an hour left? Isn’t everyone dead?) Forced labor, medical experiments, the processing of stolen goods, acts of resistance, and finally liberation—all of it was covered in what came to feel like a forced march (which, yes, was covered too). It was in the gas-chamber room, where I was introduced to a steel-mesh column that, as the wall text explained, was used to drop Zyklon B pesticide pellets into the gas chamber, killing hundreds of naked people within 15 minutes, that I began to wonder what the purpose of all this is.

I don’t mean the purpose of killing millions of people with pesticide pellets in a steel-mesh column in a gas chamber. That part, the supposedly mysterious part, is abundantly clear: People will do absolutely anything to blame their problems on others. No, what I’m wondering about is the purpose of my knowing all these obscene facts, in such granular detail.

I already know the official answer, of course: Everyone must learn the depths to which humanity can sink. Those who do not study history are bound to repeat it. I attended public middle school; I have been taught these things. But as I read the endless wall texts describing the specific quantities of poison used to murder 90 percent of Europe’s Jewish children, something else occurred to me. Perhaps presenting all these facts has the opposite effect from what we think. Perhaps we are giving people ideas.

I don’t mean giving people ideas about how to murder Jews. There is no shortage of ideas like that, going back to Pharaoh’s decree in the Book of Exodus about drowning Hebrew baby boys in the Nile. I mean, rather, that perhaps we are giving people ideas about our standards. Yes, everyone must learn about the Holocaust so as not to repeat it. But this has come to mean that anything short of the Holocaust is, well, not the Holocaust. The bar is rather high.

Shooting people in a synagogue in San Diego or Pittsburgh isn’t “systemic”; it’s an act of a “lone wolf.” And it’s not the Holocaust. The same is true for arson attacks against two different Boston-area synagogues, followed by similar attacks on Jewish institutions in Chicago a few days later, along with physical assaults on religious Jews on the streets of New York—all of which happened within a week of my visit to the Auschwitz show.

Lobbing missiles at sleeping children in Israel’s Kiryat Gat, where my husband’s cousins spent the week of my museum visit dragging their kids to bomb shelters, isn’t an attempt to bring “Death to the Jews,” no matter how frequently the people lobbing the missiles broadcast those very words; the wily Jews there figured out how to prevent their children from dying in large piles, so it is clearly no big deal.

Doxxing Jewish journalists is definitely not the Holocaust. Harassing Jewish college students is also not the Holocaust. Trolling Jews on social media is not the Holocaust either, even when it involves Photoshopping them into gas chambers. (Give the trolls credit: They have definitely heard of Auschwitz.) Even hounding ancient Jewish communities out of entire countries and seizing all their assets—which happened in a dozen Muslim nations whose Jewish communities predated the Islamic conquest, countries that are now all almost entirely Judenrein—is emphatically not the Holocaust. It is quite amazing how many things are not the Holocaust.

The day of my visit to the museum, the rabbi of my synagogue attended a meeting arranged by police for local clergy, including him and seven Christian ministers and priests. The topic of the meeting was security. Even before the Pittsburgh massacre, membership dues at my synagogue included security fees. But apparently these local churches do not charge their congregants security fees. The rabbi later told me how he sat in stunned silence as church officials discussed whether to put a lock on a church door. “A lock on the door,” the rabbi said to me afterward, stupefied.

He didn’t have to say what I already knew from the emails the synagogue routinely sends: that it’s increased the rent-a-cops’ hours, that it’s done active-shooter training with the nursery-school staff, that further initiatives are in place which “cannot be made public.” “A lock on the door,” he repeated, astounded. “They just have no idea.”

He is young, this rabbi—younger than me. He was realizing the same thing I realized at the Auschwitz exhibition, about the specificity of our experience. I feel the need to apologize here, to acknowledge that yes, this rabbi and I both know that many non-Jewish houses of worship in other places also require rent-a-cops, to announce that yes, we both know that other groups have been persecuted too—and this degrading need to recite these middle-school-obvious facts is itself an illustration of the problem, which is that dead Jews are only worth discussing if they are part of something bigger, something more. Some other people might go to Holocaust museums to feel sad, and then to feel proud of themselves for feeling sad. They will have learned something important, discovered a fancy metaphor for the limits of Western civilization. The problem is that for us, dead Jews aren’t a metaphor, but rather actual people we do not want our children to become.

The Auschwitz exhibition labors mightily to personalize, to humanize, and these are exactly the moments when its cracks show. Some of the artifacts have stories attached to them, such as the inscribed tin engagement ring a woman hid under her tongue. But most of the personal items—a baby carriage, a child’s shoe, eyeglasses, a onesie—are completely divorced from the people who owned them.

The audio guide humbly speculates about who these people might have been: “She might have been a housewife or a factory worker or a musician …” The idea isn’t subtle: This woman could be you. But to make her you, we have to deny that she was actually herself. These musings turn people into metaphors, and it slowly becomes clear to me that this is the goal. Despite doing absolutely everything right, this exhibition is not that different from “Human Bodies,” full of dead people pressed into service to teach us something.

At the end of the show, onscreen survivors talk in a loop about how people need to love one another. While listening to this, it occurs to me that I have never read survivor literature in Yiddish—the language spoken by 80 percent of victims—suggesting this idea. In Yiddish, speaking only to other Jews, survivors talk about their murdered families, about their destroyed centuries-old communities, about Jewish national independence, about Jewish history, about self-defense, and on rare occasions, about vengeance. Love rarely comes up; why would it? But it comes up here, in this for-profit exhibition. Here is the ultimate message, the final solution.

That the Holocaust drives home the importance of love is an idea, like the idea that Holocaust education prevents anti-Semitism, that seems entirely unobjectionable. It is entirely objectionable. The Holocaust didn’t happen because of a lack of love. It happened because entire societies abdicated responsibility for their own problems, and instead blamed them on the people who represented—have always represented, since they first introduced the idea of commandedness to the world—the thing they were most afraid of: responsibility.

Then as now, Jews were cast in the role of civilization’s nagging mothers, loathed in life and loved only once they are safely dead. In the years since I walked through Auschwitz at 15, I have become a nagging mother. And I find myself furious, being lectured by this exhibition about love—as if the murder of millions of people was actually a morality play, a bumper sticker, a metaphor. I do not want my children to be someone else’s metaphor. (Of course, they already are.)

My husband’s grandfather once owned a bus company in Poland. Like my husband and some of our children, he was a person who was good at fixing broken things. He would watch professional mechanics repairing his buses, and then never rehired them: He only needed to observe them once, and then he forever knew what to do.

Years after his death, my mother-in-law came across a photograph of her father with people she didn’t recognize: a woman and two little girls, about 7 and 9 years old. Her mother, also a survivor, reluctantly told her that these were her father’s original wife and children. When the Nazis came to her father’s town, they seized his bus company and executed his wife and daughters in front of him. Then they kept him alive to repair the buses. They had heard that he was good at fixing broken things.

The Auschwitz exhibition does everything right, and fixes nothing. I walked out of the museum, past the texting joggers by the cattle car, and I felt utterly broken. There is a swastika on a desk in my children’s public middle school, and it is no big deal. There is no one alive who can fix me.