In a Bill Clinton Portrait, the Devil's in a Blue Dress

Nelson Shanks says his presidential painting features a reference to Monica Lewinsky's infamous outfit.

The nation just can't get enough of blue dresses, can it?

No sooner had the furor over a blue-and-black dress (or is it gold and white?) subsided than painter Nelson Shanks sparked his own kerfuffle in an interview with the Philadelphia Daily News. Asked if any commissions had been particularly challenging, the veteran celebrity portraitist—he also painted Ronald Reagan and Princess Diana, among others—named his presidential portrait of Bill Clinton:

Clinton was hard. I'll tell you why. The reality is he's probably the most famous liar of all time. He and his administration did some very good things, of course, but I could never get this Monica thing completely out of my mind and it is subtly incorporated in the painting.

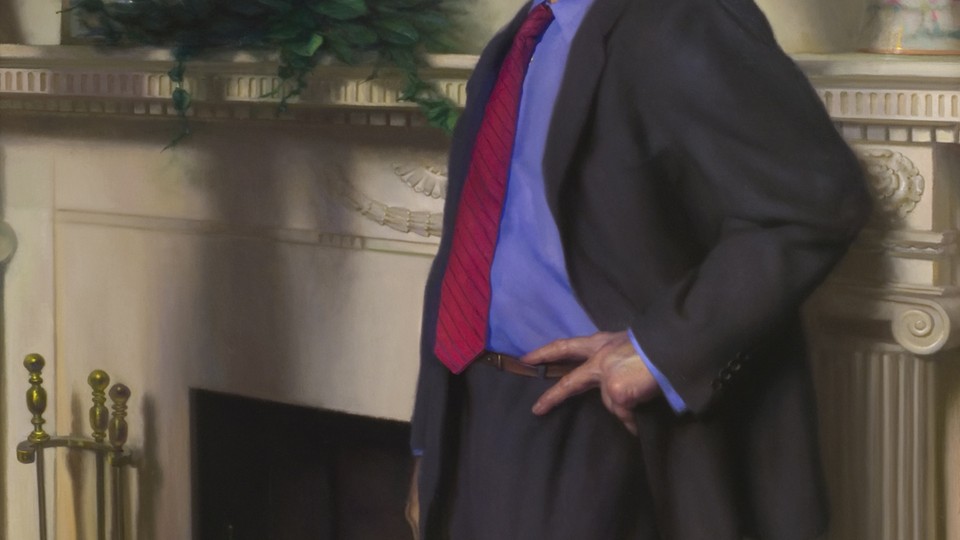

If you look at the left-hand side of it there's a mantle in the Oval Office and I put a shadow coming into the painting and it does two things. It actually literally represents a shadow from a blue dress that I had on a mannequin, that I had there while I was painting it, but not when he was there. It is also a bit of a metaphor in that it represents a shadow on the office he held, or on him.

And so the Clintons hate the portrait. They want it removed from the National Portrait Gallery. They're putting a lot of pressure on them.

There is, as they say, a lot to unpack here. Is Clinton really the most famous liar of all time? (Um.) Is it impressive commitment to verisimilitude or just weird that Shanks used an actual blue dress to produce the shadow? How did the Clintons figure out the secret code when no one else had? And are they really pushing the Portrait Gallery to remove it?

The answer to the last query is simple, according to a spokesperson for the National Portrait Gallery: no. Bethany Bentley said the Clintons have done no such thing. And she noted that the painting isn't exactly the single, definitive Clinton portrait. There are some 55 Clinton images in the gallery's collection, and they're occasionally rotated on and off view. While one formal portrait is always on display, that's currently Chuck Close's likeness—an image that manages to be at once both more abstract and more staid and straightforward.

When he was working on the painting prior to its unveiling in 2006, Shanks described it in terms strikingly at odds with his current account. "There are times when I love to play all kinds of complicated games in painting," he told The Philadelphia Inquirer. "But I think this is one case when I need to be fairly straightforward. I'll just try to paint the man, his intelligence, his amiability and his stature, maybe paint him fairly close to humor and try to get it just right."

Perhaps Shanks decided to add the dress later—or perhaps, taking a cue from the dissembling ways of his subject, he opted to hide it. (When you're a portrait painter, there's little chance you'll be impeached for perjury.) But Robert Langdon's fever dreams aside, there's a long tradition of artists hiding symbols and cryptic messages in works commissioned by the rich and famous—sometimes with the commissioner's collusion, and sometimes not.

Take Herbert Abrams's portrait of George H.W. Bush. Behind the president is George P.A. Healey's "The Peacemakers," a painting of Abraham Lincoln meeting with Generals Ulysses Grant and William Sherman and Admiral David Porter in the closing days of the Civil War. Its inclusion is apparently a nod to Bush's international successes—the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the defeat of Saddam Hussein in the first Gulf War.

Gilbert Stuart's image of George Washington includes symbols of the Roman republic and of American democracy. Aaron Shikler's posthumous portrait of John F. Kennedy famously shows the president looking down, so that his face is obscured. That was Jackie Kennedy's request, he told People: "The only stipulation she made was, 'I don't want him to look the way everybody else makes him look, with the bags under his eyes and that penetrating gaze. I'm tired of that image.'"

Often, however, the symbolism is more straightforward. Mitt Romney's Massachusetts gubernatorial portrait featured both his beloved wife, Ann, and a caduceus-embossed folder to represent the healthcare law he shepherded.

But it's the wry, playful, and pointed hidden messages that are the most fun. The designer Alexander McQueen, while an apprentice on Savile Row, claimed to have chalked an unprintable message into a suit being made for Prince Charles.

Shanks's gesture is in a way much bolder—after all, it would require ripping out the seams of an immaculately tailored suit to detect McQueen's graffiti—and a bit of letdown. How subversive can a hidden meaning be once it has been revealed to the world?

More to the point, is what Shanks did inappropriate? It's not as if the painting was a private commission for the Clintons that Shanks sabotaged: It's a bequest to the nation and to the National Portrait Gallery. (The portrait was commissioned by the gallery and paid for with private donations.) The Lewinsky scandal was a key moment in the Clinton presidency. A consistent two-thirds of Americans have a favorable impression of Bill Clinton, but popular forgiveness doesn't mean the scandal didn't happen and isn't worth recording.

The softly menacing shadow cast by the unseen blue dress reminds me of Hans Holbein the Younger's "The Ambassadors." The two richly attired men stare out at the viewer—more somber than Clinton, but similarly assured of their own prowess. But across the bottom of the painting is a bizarre, unintelligible streak. Viewed from the right angle, it's anamorphic skull, a memento mori that takes the edge off their grandeur. In the same way, the shadow casts just enough pall on Clinton's image, a reminder of the turbulence in an administration otherwise viewed fondly by many citizens. Such a reminder adds depth without overwhelming the whole image. It's also a good democratic practice—in a portrait meant for national remembrance, Shanks is exercising his right to needle authority.

At a time when debates about political portraits tend to come down to either stale rehashes of early-20th-century art controversies (abstraction! No, realism!) or lamentations over poorly painted likenesses, it's refreshing to be able to debate more nuanced symbolism. If only Shanks had trusted his work to speak for itself.