The Qtub Minar and the Verticality of Minarets

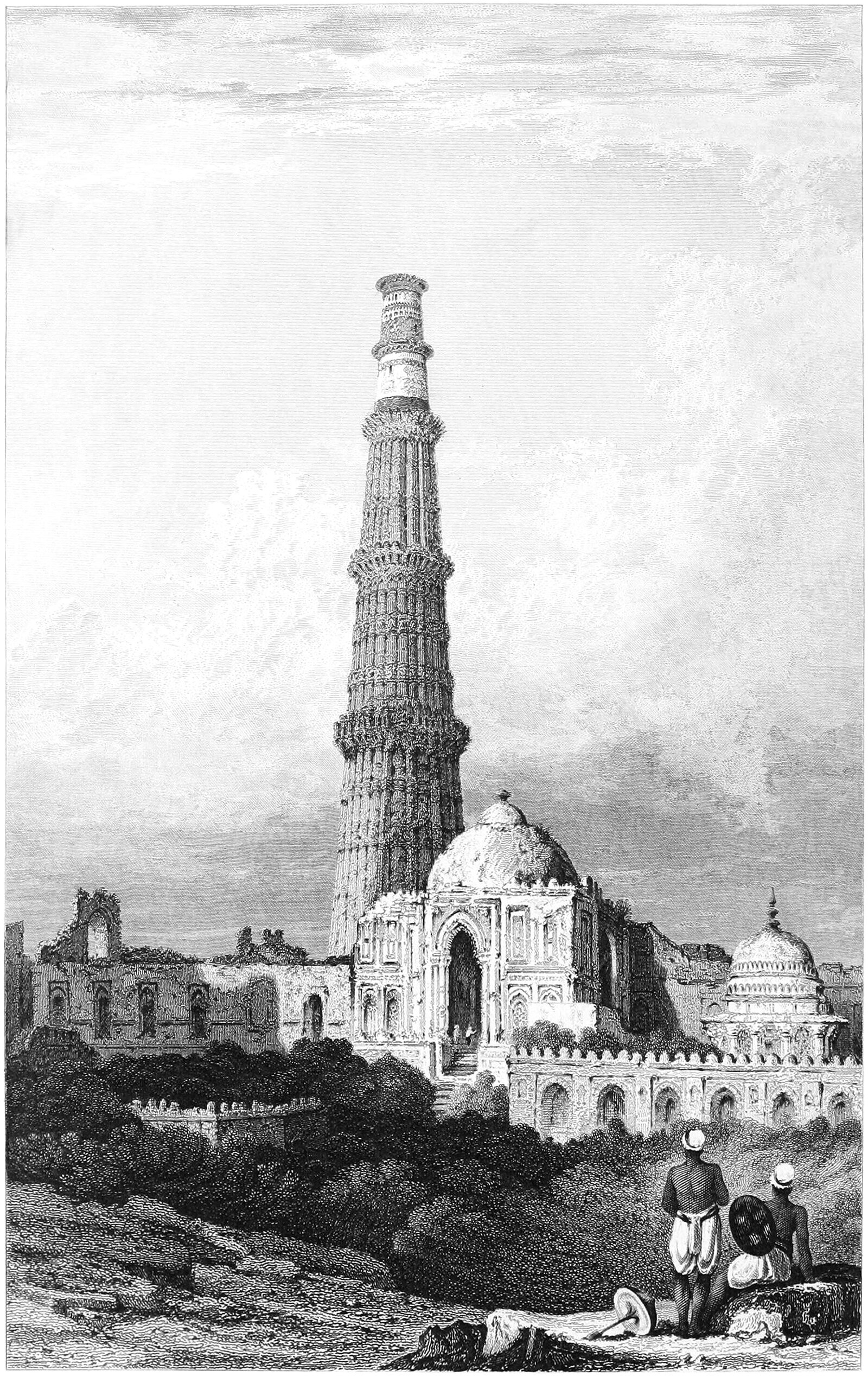

Illustration by Samuel Prout from 1858, showing the Qtub Minar, which is part of the Qtub complex in Delhi, India. The minaret provides a landmark for the site, greatly increasing its visibility to the surrounding landscape.

Minarets are tall towers that generally accompany a Muslim mosque. They serve multiple purposes. First, their height makes them landmarks, announcing their presence to the surrounding landscape, much like a bell tower or spire does for a Christian church. Second, they are usually used for the Muslim call to prayer, or adhan. Traditionally, a man would ascend the tower and loudly announce the call to prayer five times a day. The height of the minaret allowed his voice to be easily heard. Third, the tower element differentiated a mosque from surrounding buildings, which called attention to the Muslim religion and provided a reference point for local Muslims to come and worship at the mosque.

Each of these functions is based on verticality. By building a tower element adjacent to a mosque, the Muslim religion is asserting its presence to the surrounding landscape. The taller these elements get, the more impressive they become and the further away the adhan can be heard. In this sense, verticality is the currency that drives the utility of a minaret.

Minarets are most common in the Middle East, which is the cradle of the Muslim religion. Ancient examples do exist outside this region, however. Pictured above is the Qtub Minar, which was built around 1200 just outside Delhi, India. It’s a fascinating example of a cross-culture artifact, and it departs from traditional minarets in three ways. First, it was built as the focal point of the Qutb complex and exists on its own, without an adjacent mosque.[1] Second, it was built as a victory tower as well as a minaret. This means it was partly a monument to military victories, much like a triumphal column in Ancient Rome. Lastly, the minaret was designed by Muslim architects, but built by Hindu craftsman and laborers. Thus, the artifact is a synthesis of Muslim and Hindu traditions. The Hindu influence can be seen in the detailing and ornament, which is reminiscent of Hindu temple architecture.

One thing common to both cultures was verticality. The three main functions of a minaret discussed above are present at Qtub, but the addition of the victory tower function gives the tower further meaning to the surrounding city. Still, each of these functions are based on verticality, and the height of the minaret gives it more meaning, especially since it’s the only tower element in the area. Pictured below is a watercolor from 1805 showing the Qtub complex. It’s easy to see the effect verticality has, with the minaret dominating the entire area, thus projecting a sense of importance and meaning to the site.

Watercolor from 1805 by Thomas Daniell showing the Qtub complex, with the minaret dominating the entire area.

I love buildings like the Qtub Minar, because they are the result of a specific time and place in history. Its design was influenced by two different cultures that were present in Delhi at the time, and the outcome is a unique building that tells a story about these two cultures. The common root of both, of course, is verticality. A tall tower served the purposes of both cultures perfectly, and the result was an iconic landmark that still stands and is still relevant today. This is the power of verticality.

Read more about how minarets fit into the main Theory of Verticality here.

[1] : There is a mosque nearby, however. The Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque is located to the northwest of the minaret, but both buildings are distinct and the minaret stands alone.