The oldest city of the Netherlands, Nijmegen, is located in the eastern part of the country, close to the border with Germany. Like most cities situated along rivers, Nijmegen has a long love-hate relationship with the river Waal, the main branch of the Rhine, which acted throughout history both as a source for economic prosperity and as a threat in times of war or flooding. The lower parts of Nijmegen and the surrounding floodplain areas have been for centuries sensitive to high water levels and swirling currents because the river Waal sharply bends and narrows east of the city, thus forming a bottleneck in the flow of the river.

Jan van Goyen’s painting of Nijmegen, with the river Waal and the the Valkhof castle, 1641.

Jan van Goyen’s painting of Nijmegen, with the river Waal and the the Valkhof castle, 1641.

Courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

One of the latest, severe flooding episodes that threatened the city took place in January 1995, when the Waal swelled due to heavy rainfalls in western Europe, and the snow melting and frozen soil in the higher uplands. According to an interviewee, this happened because the Rhine “is a mixed river, its water levels are dependent on rainfall, but also on the regime of snow higher up in the mountains.” As the water levels were raising to alarming heights, the dikes started to show signs of instability and possible collapse. Worried by the possible effects, on 31 January 1995, the Dutch authorities ordered the evacuation of tens of thousands of people from the low-lying areas along the river. Fortunately, the dikes did not collapse, the water started to recede, and people could return safely to their homes in a few days.

Nijmegen riverfront during the 1995 floods.

Nijmegen riverfront during the 1995 floods.

Photograph by Henk Baron, 1995. https://henkbaron.nl

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The repeated danger of flooding from the mid-nineties and the increased recognition of climate change effects led to social awareness about flood protection issues and, among experts and policy makers, to the acknowledgment of the limits of building vertical flood defences to cope with high water levels. This led to policy change with respect to dealing with river floods, and to a paradigm shift in the Dutch water management sector, which moved from “fighting the water” to “making room for water”. The emblem of this paradigm shift is the “Room for the River” national programme, which is internationally considered a leading example of integrated flood risk management and multi-level governance.

At the beginning of the 2000s, it became clear that one of the key locations for testing and implementing this new approach was the bottleneck in the river Waal at Nijmegen. In this specific place, “making room for the river” involved: relocating the existing dike, situated on the northern shore of the Waal at the village of Lent, 350 meters inland; the excavation of a new ancillary channel; and the creation of a river island in-between. Due to the project’s location in the oldest city of the Netherlands, and its impact on an already inhabited area, the original plan faced much opposition and controversies. Firstly, the municipality of Nijmegen was surprised by this proposal, especially because it had just received approval for the development of a large housing project (“Waalsprong”) on the northern shore of the Waal, in the village of Lent, which could be affected by the flood risk management plans. Secondly, similarly unenthusiastic were the residents of Lent, whose properties, situated in the future project area, had to disappear to give more space to the river Waal.

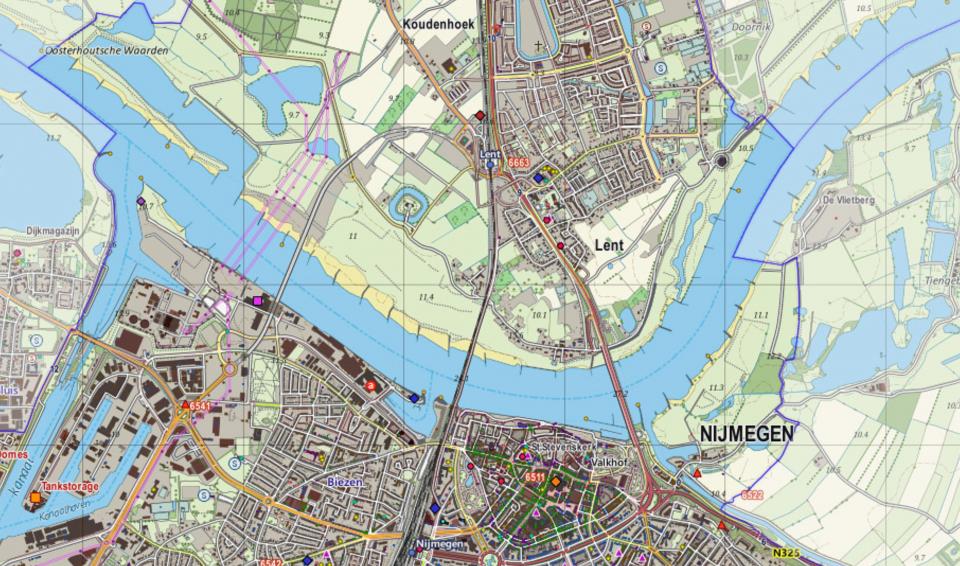

Topographic map of Nijmegen (southern shore of the Waal) and Lent (northern shore of the Waal) in 2013, before the relocation of the dike and the excavation of the ancillary channel.

Topographic map of Nijmegen (southern shore of the Waal) and Lent (northern shore of the Waal) in 2013, before the relocation of the dike and the excavation of the ancillary channel.

Map by Jan-Willem van Aalst, 2013. This map has been cropped.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 6 October 2021. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Topographic map of Nijmegen (southern shore of the Waal) and Lent (northern shore of the Waal) in 2020, after the implementation of the Room for the River Waal project. October 2020.

Topographic map of Nijmegen (southern shore of the Waal) and Lent (northern shore of the Waal) in 2020, after the implementation of the Room for the River Waal project. October 2020.

Detail of map compiled by Jan-Willem van Aalst. http://www.opentopo.nl

For information on the source data, click here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The residents opposed the plans and came up with an alternative one, which did not fulfil the river discharge conditions set by the government. However, the municipality realized that the dike relocation would be an opportunity for the urban renewal of the city. Consequently, the municipality made a series of agreements with the national government, one being aimed at the creation of a new bridge over the Waal that would solve the city’s mobility and accessibility issues. Furthermore, the flood management project triggered the urban renewal of Nijmegen’s riverfront and the major redevelopment of the Lent village. Given these developments, the city of Nijmegen is now truly embracing the river Waal, which is not perceived anymore as a barrier, but as a connecting blue-green space that, together with the river island park in the middle, offers the city, its inhabitants, and visitors recreational opportunities.

Panorama photograph of the river Waal, with the ancillary channel (de Spiegelwaal) and the river island.

Panorama photograph of the river Waal, with the ancillary channel (de Spiegelwaal) and the river island.

Photograph by DaMatriX, 2017.

Accessed via Wikimedia. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Having started as a project surrounded by protests and controversies and having ended as a leading example of the paradigm shift in the Dutch water management, the Nijmegen case can be a source of valuable lessons. Firstly, adopting an integrated water management and multi-level governance approach is not easy but worthwhile, it asks for taking decisions that may not be liked by everyone, and poses many challenges as it requires new ways of working, in which multiple actors from different sectors and levels, and their multiple interests are brought together. Secondly, the project showed that water management issues can be coupled with other spatial issues like recreation, nature, mobility, thus leading to smart combinations of solutions that benefit also the city. Thus, water management projects should not only focus on technical and financial aspects, but should also pay attention to the spatial quality aspects directly impacting the daily lives of people. The final lesson is that climate change and climate adaptation have spatial implications and this case from the Netherlands shows the importance of a paradigm shift in water management that is relevant to many other flood-prone cities and regions: to embrace living with water.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a project that received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 765389.

How to cite

Rădulescu, Maria Alina, Leendertse Wim, and Jos Arts. “Metamorphosis of a Waterway: The City of Nijmegen Embraces the River Waal .” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2021), no. 29. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9357.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2021 Maria Alina Rădulescu, Wim Leendertse, and Jos Arts

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Brink, Margo van den. Rijkswaterstaat on the Horns of a Dilemma. Delft: Eburon, 2009.

- Busscher, Tim, Margo van den Brink, and Stefan Verweij. “Strategies for Integrating Water Management and Spatial Planning: Organising for Spatial Quality in the Dutch ‘Room for the River’ Program.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 12, no. 1 (2019): 1–12. doi:10.1111/jfr3.1244.

- de Bruijn, Hans, Mark de Bruijne, and Ernst ten Heuvelhof. “The Politics of Resilience in the Dutch ‘Room for the River’-Project.” Procedia Computer Science 44 (2015): 659–68. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.03.070

- Disse, Markus, and Heinz Engel. “Flood Events in the Rhine Basin: Genesis, Influences and Mitigation.” Natural Hazards: Journal of the International Society for the Prevention and Mitigation of Natural Hazards 23, no. 2–3 (2001): 271–90. doi:10.1023/A:1011142402374

- Edelenbos, Jurian, Arwin Van Buuren, Dik Roth, and Madelinde Winnubst. “Stakeholder Initiatives in Flood Risk Management: Exploring the Role and Impact of Bottom-Up Initiatives in Three ‘Room for the River’ Projects in the Netherlands.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60, no. 1 (2017): 47–66. doi:10.1080/09640568.2016.1140025

- Klijn, Frans, Dick de Bruin, Maurits C. de Hoog, Sjef Jansen, and Dirk F. Sijmons. “Design Quality of Room-For-The-River Measures in the Netherlands: Role and Assessment of the Quality Team (q-Team).” International Journal of River Basin Management 11, no. 3 (2013): 287–99. doi:10.1080/15715124.2013.811418

- Sijmons, Dirk, Yttje Feddes, Eric Luiten, Fred Feddes, and Jeroen Bosch. Room for the River: Safe and Attractive Landscapes. Wageningen: Uitgeverij Blauwdruk, 2017.