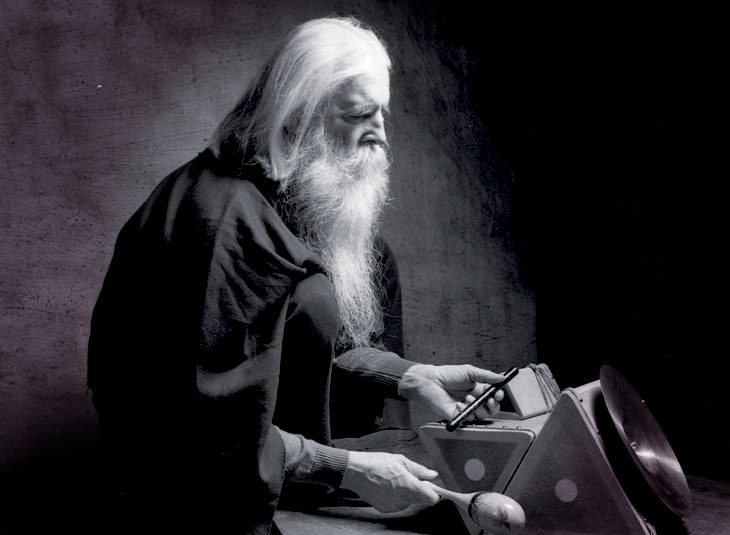

If people saw him as a living anachronism between the skyscrapers of Midtown, it should be said the feeling was mutual. Moondog claimed he never felt like an American. He idealized Northern Europe and referred to himself as a European in exile. When the music brought him to Germany in 1974, he was delighted to visit sites such as Teutoburg Forest, where Germanic tribes under the military leadership of Arminius lay waste to three Roman legions in the year 9 CE. As well as the Sachsenhain monument in Verden, where Charlemagne allegedly subjected thousands of pagan Saxons to forced baptism, before executing them en masse on the banks of the rivers Aller and Weser. These pilgrimages must have spoken to Moondog's yearning towards a more native and ancient atmosphere, as well as the Machiavellian sentiments of his personal philosophy. Every now and then, I make little pilgrimages of my own to Moondog's corner, where only his ghost remains to those who still remember, or are otherwise initiated into the secret of his existence.

While people tend to imagine Moondog busking on “his corner” on 6th Ave, this was not usual. For the most part, Moondog’s daily routine consisted of standing in the shadow of the Manhattan skyline, tapping along as he wrote music in braille. He composed poetry, sold his own sheet music, sipped coffee, relished the sounds and rhythms of the city, chatted with strangers, joked with friends, and disarmed hecklers, rain or shine. For his poetic and philosophical content he relied heavily on the mnemnonic wonders of poetry, much like skaldic poets and bards did in the absence of the written word. When he wrote these poems down, he usually kept it down to only a few keywords in braille in which the poems were immanent, and used them recall their poetic content and structure like a true singer of tales. He composed hundreds of simple couplets in iambic septameter, mapping his unique view of the world. Here are but a few:

᛫ It seems that hills are made to fall, that dales were made to rise,

that mediocre nondescripts were made to compromise.

᛫ The only one that knows this ounce of words is just a token,

is he who has a ton to tell, but must remain unspoken

᛫ We grope with eyes wide open toward the darkness of futurity,

with faith in outermost instead of innermost security.

᛫ We were few and far between in prehistoric times,

and we'll be few and far between in posthistoric times.

᛫ There was a time when goods were made for wear instead of tear.

There is a time when goods are made for tear instead of wear.