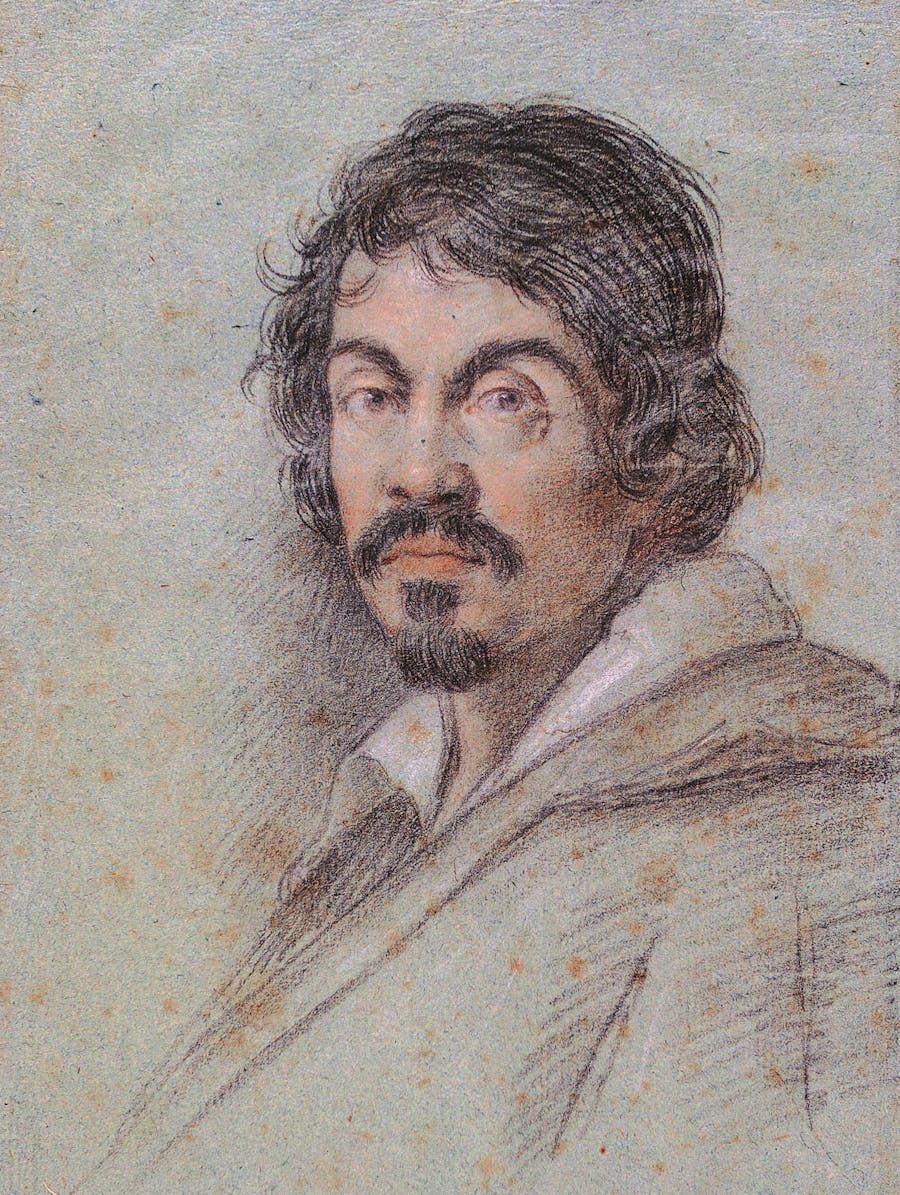

Caravaggio: The Renaissance Rebel

Delve into the history of the master of chiaroscuro.

Michelangelo Merisi, also known as Caravaggio, wasn’t even 20 years old when he decided to leave his native region of Lombardy for Rome. Trained in Milan, the young artist already had a certain penchant for provocation at a time – the late 16th century – when baroque art, so cherished by the Catholic Church, was just taking form.

Nevertheless, during his career Caravaggio never wanted to turn to this pompous style, preferring an uncompromising naturalism that became the hallmark of his works.

More than 400 years have passed since the death of Caravaggio, but his works are still popular because of their timelessness. The paintings of the master are characterized by an incomparable liveliness that leads his figures out of the shadows and into radiant light, a study in chiaroscuro. However, this direct ‘divine’ light was perceived by the church as deeply offensive. When Caravaggio painted the Death of the Virgin Mary in 1606 – one of the most beautiful works of the 17th century in the Louvre today – there was an outcry in church circles. They expressed their horror that the Mother of God was disrespectfully portrayed as a barefoot, suffering woman wearing a simple robe.

However, it was not just Caravaggio's paintings that caused a sensation. His life was short – he died at just 38 years old – and in many ways scandalous. When he wasn’t painting pictures, he found himself in fights and prison. He was even accused of assassinating a counterpart at the gaming table.

Yet Caravaggio left behind an enormous legacy to European artistic culture. Today, 70 paintings by this extravagant and precocious figure are found all over the world. These include his earliest works, such as still lifes like Basket of Fruit, through which he declared his devotion to realism.

Related: Artemisia Gentileschi: 5 Extraordinary Facts

However, it was the religious and biblical themes that established his fame and at the same time branded him a provocateur. At the time of their creation, they were often condemned as too realistic – a blasphemous term at the time.

At the age of just 27, Caravaggio received his first prestigious commission for the San Luigi dei Francesi church in Rome: three large paintings telling the story of Saint Matthew. Caravaggio mastered this task with flying colors. Above all, his lighting effects in The Calling of Saint Matthew, which illuminate the faces and create a silent dialogue between Christ and Matthew, make this work an absolute masterpiece.

Related: The Famed Caravaggio of Toulouse Finally Arrives at Auction

The success of this work led to further commissions, including The Entombment of Christ for the Church of Santa Maria in Vallicella. The work is now in the Vatican Museums.

However, in 1606, Caravaggio's heyday in Rome was over, and the dark side of his unbridled life gained the upper hand. After killing a man in an altercation in which he only wanted to help a friend, he was declared an outlaw in the Papal States. His only chance to survive was flight.

His travels, which were to determine the rest of his short life, first led him to the southern Italian kingdom of Naples, where he made numerous commissioned works for the nobility that received boundless admiration. He left Naples for Malta and Sicily where he produced more commissioned works in his characteristic chiaroscuro style for churches and private customers. He needed the money urgently and his debts were always on his neck. Then he returned again to Naples, producing The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula in 1610 as one of his last works.

Related: The Return of the Old Masters

In an attempt to return to the Eternal City, he boarded a ship and got caught up in a brawl during a stopover in Porto Ercole. Legend has it that he was injured and cast into prison for several days. Once freed, he died, sick and alone, on a deserted Tuscan beach.

During his lifetime, Caravaggio’s paintings were admired, even revered. So much so that they inspired many artists from Italy (Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi), the Netherlands (Dirck van Barburen) and France (Georges de la Tour) in the first half of the 17th century. They also found favor among the numerous painters who passed through Rome like Rembrandt, Ribera and Velasquez. Emulating their idol’s style, these artists created an artistic genre in its own right, called Caravaggism.

Art historian André Berne-Joffroy believed, "What begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite simply, modern painting.” No more gods, conventional nudity, heroes from antiquity: the challenge was to represent reality as it was: worn clothing, faces bearing the marks of time, gritty taverns...

Related: The Top 10 Rediscovered Masterpieces

While Caravaggism can be interpreted as a form of provocation, it also represents a return to a more natural representation of life.

Now in the 21st century, the artists who recognize Caravaggio’s influence on their works tend to come from the worlds of film and photography. You only have to see Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, or Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, to detect cinematic tributes to the artist who incontestably remains the master of chiaroscuro.