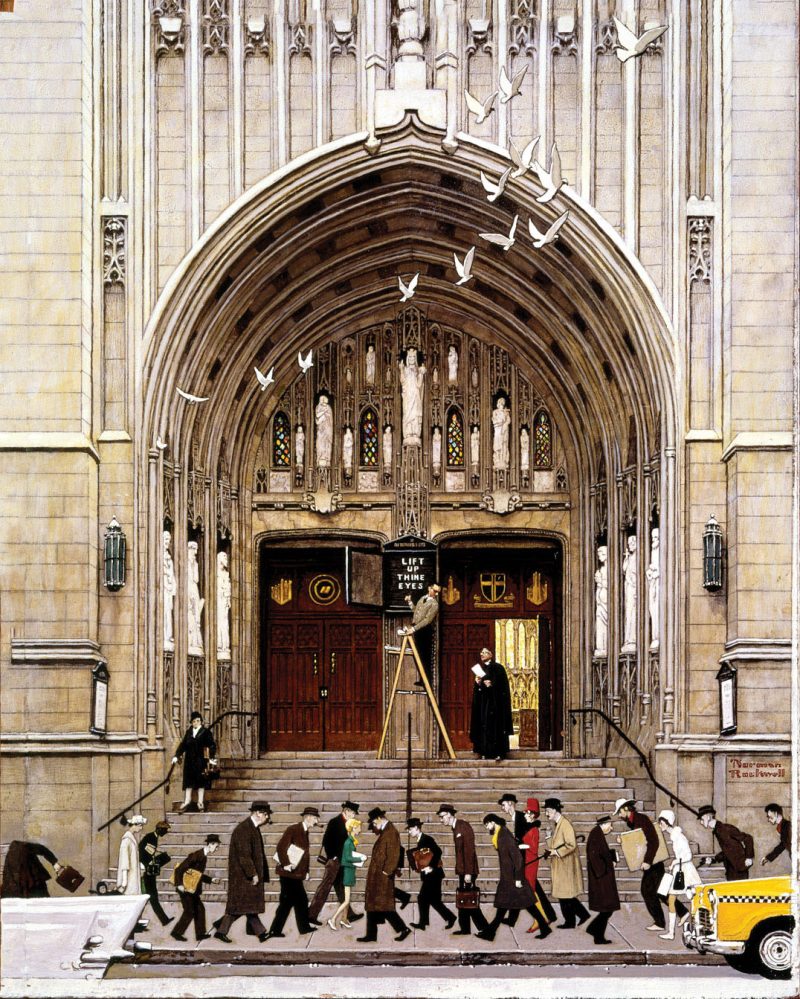

Lift Up Thine Eyes

Lift Up Thine Eyes

Norman Rockwell’s paintings offered a hopeful vision for America. Here BYU professors share personal responses to four classics.

By Lane Fischer (BS ’79, MA ’82), Celeste Beesley, Michael J. Richardson (BS ’95, PhD ’09), Christopher E. Crowe (BA ’76) in the Winter 2016 Issue

Paintings by Norman Rockwell

Cherry-cheeked Santas; stalwart, saluting Boy Scouts; a jovial soda jerk serving dreamy-eyed customers at the corner diner; impish boys in flight after sneaking a dip at a site marked No Swimming. Over 65 years and some 4,000 works, Norman Rockwell pieced together a composite portrait of America at its folksy best. Made famous by his cover art for The Saturday Evening Post, Boys’ Life, and Life, among other publications, Rockwell was called “the Dickens of the paintbrush,” and his stories starred the everyday people of Everytown, USA.

As with Lift Up Thine Eyes, part of the BYU Museum of Art (MOA) permanent collection, Rockwell’s compositions invite viewers to shift their gaze from the grime and grind of modernity to a more hopeful vision of America. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, the artist kept his focus on plucky citizens making the most of trying times. In the 1960s, as he applied his brush to social issues like segregation, his paintings encouraged better living, even when addressing uncomfortable realities.

In conjunction with American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell, a MOA exhibit running through Feb. 13, BYU Magazine invited professors across campus to respond with brief personal essays to classic Rockwell images. The authors’ reflections—whimsical, academic, personal, poignant—underscore the paintings’ continued relevance in American iconography.

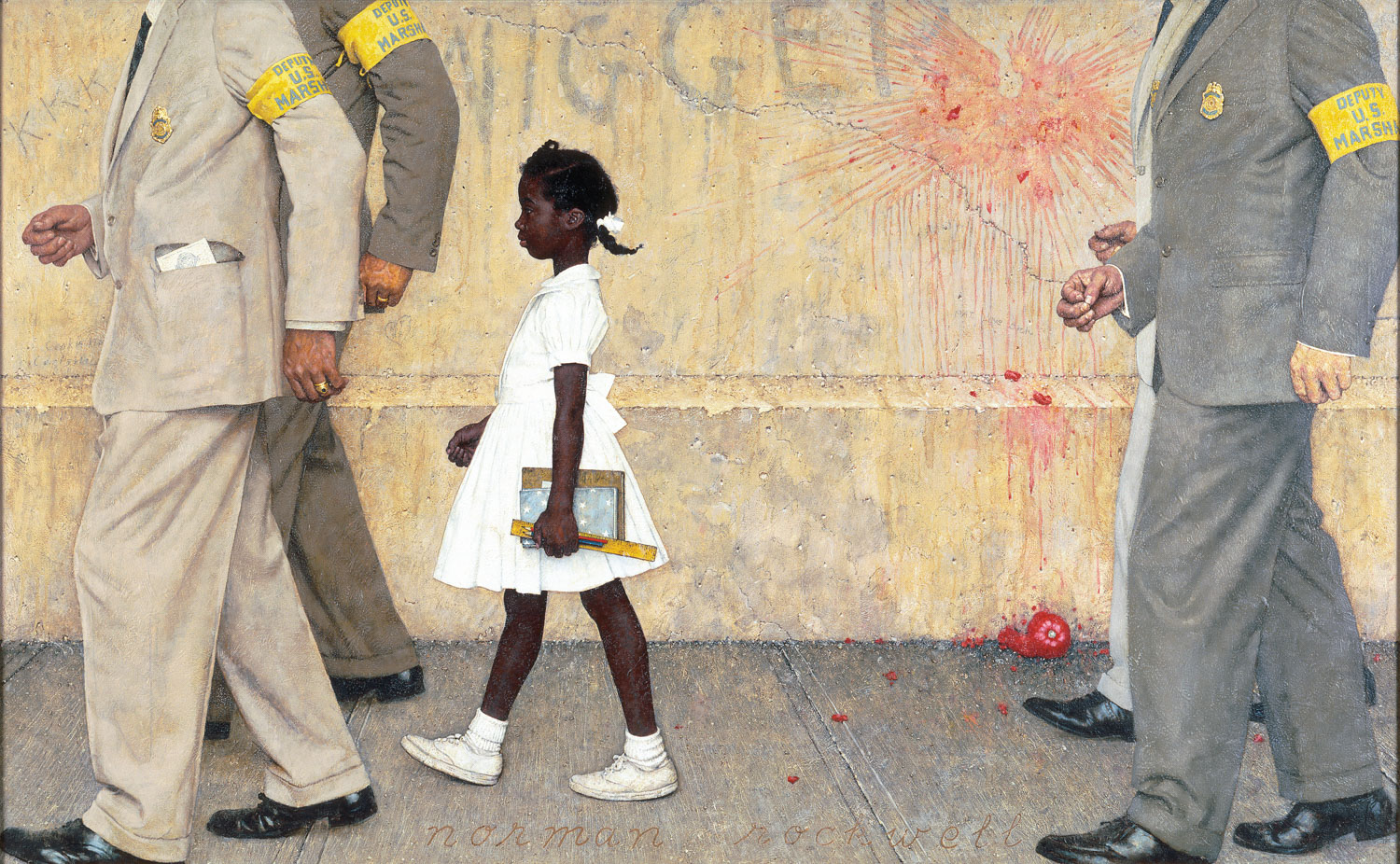

No Easy Walk to Freedom

By Lane Fischer (BS ’79, MA ’82), Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology and Special Education

The Problem We All Live With, 1964

My father was a Jew. He became a Latter-day Saint after privately studying the Book of Mormon. I am a Latter-day Saint, and I am from the tribe of Judah. My family history sensitizes me to my forefathers’ travail. It is a common travail.

In the 19th century, Eastern European governments were openly anti-Semitic. Indeed, between 1885 and 1898 Romanian governmental sanctions increasingly restricted Jews’ schooling and presence in the professions and trades. The government rigorously enforced prohibitions on any trade with Jews. And so Jews began to starve. In 1899 the wheat harvest was poor. Economic depression set in. As before and after, the Jews were scapegoated. A brutal pogrom was carried out in Iasi, Romania.

With no hope of civil rights or protections in their home country, Romanian Jews began to flee on foot. They were called fusgeyers—foot-goers. Year after year, Romanian fusgeyers would set out for the West after winter broke. After climbing through the Prislop Pass in the Carpathian Mountains, they still had to brave the perils of other empires’ anti-Semitism. There was no easy walk to freedom.

“My Jews walked 1,000 miles across Europe to escape bigotry. My Latter-day Saints walked 900 miles across America. I claim the legacy of both. This demands that I extend liberty to all of God’s children.”

My great-grandfather Morris Schreiber was a fusgeyer. At 21, in 1900, the tinsmith walked out of Bucharest with two brothers and a sister-in-law. They left their parents behind, never to see them again. They walked 1,000 miles from Bucharest to Amsterdam. Kindly and powerful helpers aided them along the way, and they arrived at the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter in London on July 8. Philanthropic transmigration funds allowed them to board a converted troop carrier in Liverpool, bound for Canada. On July 24 the immigrants arrived in Montreal, where they were supported by a wealthy Jewish baron in Germany, who provided educational and employment opportunities. Morris worked his way south on the Great Lakes shipping lanes, eventually landing in Chicago, where he married my great-grandmother Schaindel Blumenfeld, who also had escaped Romanian anti-Semitism following the pogrom in Iasi in 1899. Morris and Schaindel had a daughter who had a son who became a Latter-day Saint who had a son who is a Latter-day Saint and is from the tribe of Judah.

My Jews walked 1,000 miles across Europe to escape bigotry. My Latter-day Saints walked 900 miles across America. I claim the legacy of both. This demands that I extend liberty to all of God’s children: “He inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile” (2 Ne. 26:33).

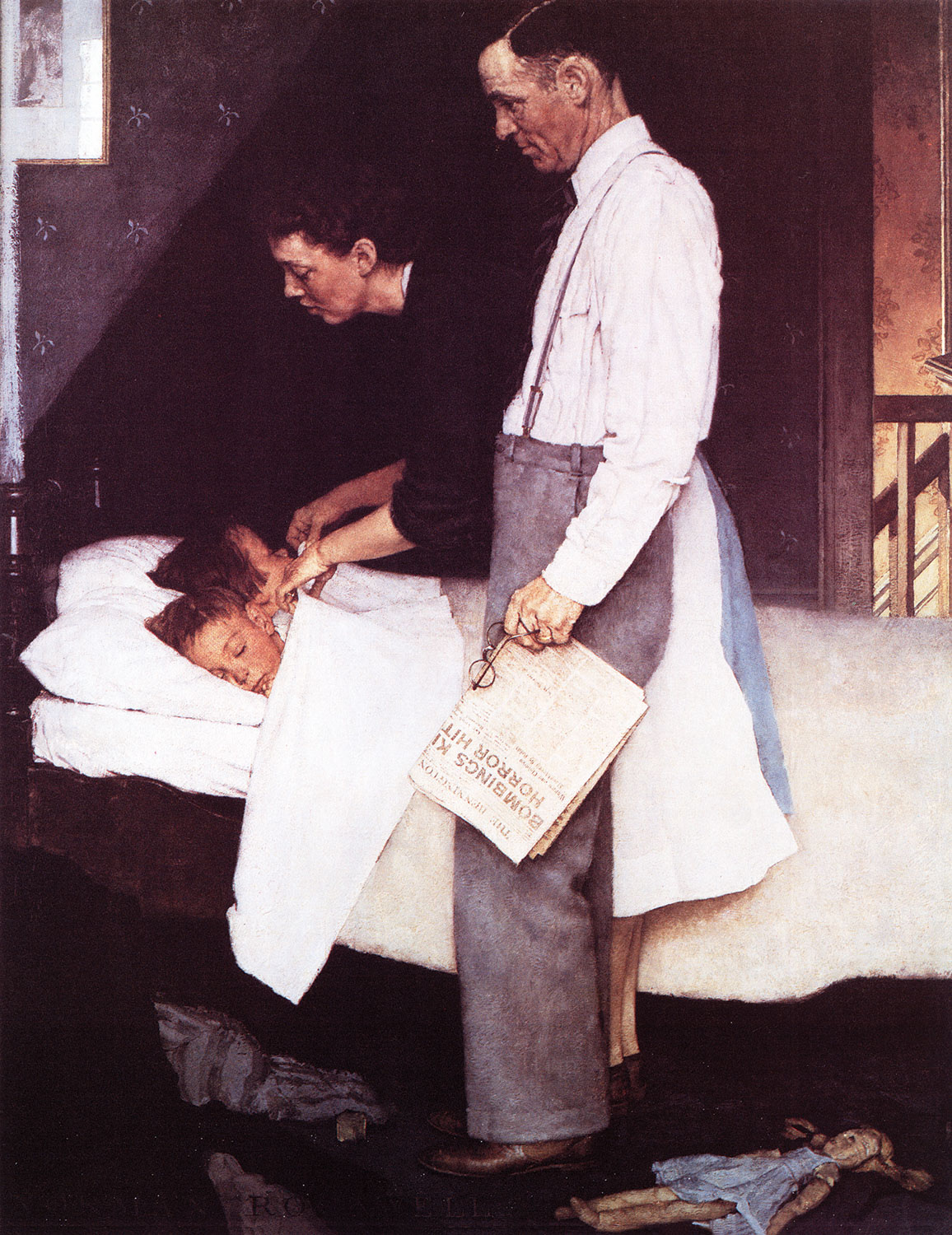

I Will Keep You Safe

By Celeste Beesley, Assistant Professor of Political Science

Freedom from Fear, 1943

Brushed teeth. Washed faces. Story time. Prayers. Kisses goodnight. I love bedtime with our four children. There is a sense of security and relief at having them all safe in bed. But sometimes, after they’re tucked in, my mind attends to questions and worries that I simply do not have time for during the day. Keeping them spiritually, emotionally, and physically safe is my purpose in life as a parent. But are they actually safe? Am I doing enough to protect them? Even with them “safe in bed,” I realize how much of their security is beyond my control. What does their future hold? Will they be safe from car accidents? Cancer? Famine? War? If you are parent, freedom from fear is an illusion.

“Words of gratitude for peace and safety soon mingle with prayers on behalf of parents and children for whom my worst fears are not far-off possibilities but daily realities.”

So I pray for them at night while they sleep. Words of gratitude for peace and safety soon mingle with prayers on behalf of parents and children for whom my worst fears are not far-off possibilities but daily realities. Teaching and studying international politics during the day, I consider these things dispassionately, as numbers, models, and incentives fill up the computer screen in front of me. But at night, as I worry and pray, the things I study become much more human. Refugees in Europe shift from a complex political problem to the desperate plight of parents clinging to sleeping children, no bed to lay them in for the night. I imagine parents consumed by fear that their home will be hit by artillery while their children sleep. I consider parents who make the awful choice to send their young teenagers on a perilous journey without them because they cannot afford to go together. These mothers and fathers live to keep their children safe, just as I do, but in their current circumstances, safety is something they cannot promise. I weep for these parents who are willing to risk great danger and sacrifice everything in exchange for a chance at a future when they too can tuck their children into bed at night and know that they are safe. Would I have their courage?

I sneak back in for another look at my sleeping children. Any annoyance at scattered toys, missing homework, piles of laundry, and multiple requests for another hug and kiss are long gone from my mind. In all this world, I do not ask for more than to know that they are safe.

The Question

By Michael J. Richardson (BS ’95, PhD ’09), Assistant Professor of Teacher Education

Girl at the Mirror, 1954

Her question is unexpected, perhaps marking the beginning of my midlife crisis. I’m pleased that she asks me. It seems to be an expression of confidence in her father. Still, I’m worried. It seems to be the wrong question, and not just for a 12-year-old girl. But how can I make her understand, when so many voices seem to be telling her that this is the question? My resolve not to answer her directly—not just yet—weakens at her visible disappointment. “Dad, I won’t try it now. I’ll wait ’til later, but I really want to know.” She asks again: “How do I attract boys?”

Perhaps she doesn’t know the feeling that her mother had during her first pregnancy as she prayed in gratitude for this daughter—that during that prayer of thanks for such an amazing gift, another Father glanced at the child and said, “You have no idea how amazing she is . . .”

“The look of concern on her face—or any girl’s face—as she wonders whether she will be loved feels incongruous, like light wondering whether darkness will comprehend it. Comprehended or not, it still shines.”

And at 12 she had no idea that a few years hence her uncanny knack for attracting boys of all sorts might trouble her mortal dad, along with some of those very boys. Or that other gifts—to heal hearts and minds—would become so much more important to her. Her name, Alexis, means “helper, defender”—a prescient choice.

But how do I help her? The look of concern on her face—or any girl’s face—as she wonders whether she will be loved feels incongruous, like light wondering whether darkness will comprehend it. Comprehended or not, it still shines.

Still, her face begs an answer from the man she knows best, not as a developmental psychologist but simply as Dad. The mirror won’t tell her. She sees her reflection only dimly, through pop culture and peers. The things that prompt the question seem to promise answers: magazine cover, billboard, TV, prom queen. But these only obscure, beg dubious comparison. She needs to know what matters most, and this question—troubling as it might be for a father to hear—is an opportunity.

“I’ll tell you this much,” I relent, “if you want a strong man, be strong. If you want a smart man, be smart. If you want a spiritual man, be spiritual.”

I don’t think the answer satisfies her, and years later when I remind her of the conversation, she doesn’t seem to remember. But the advice is unnecessary anyway. She is, and was, all of these things and much more. It seems unnecessary to say to a light, “Shine!” But now I think it might have been all that ever needed to be said.

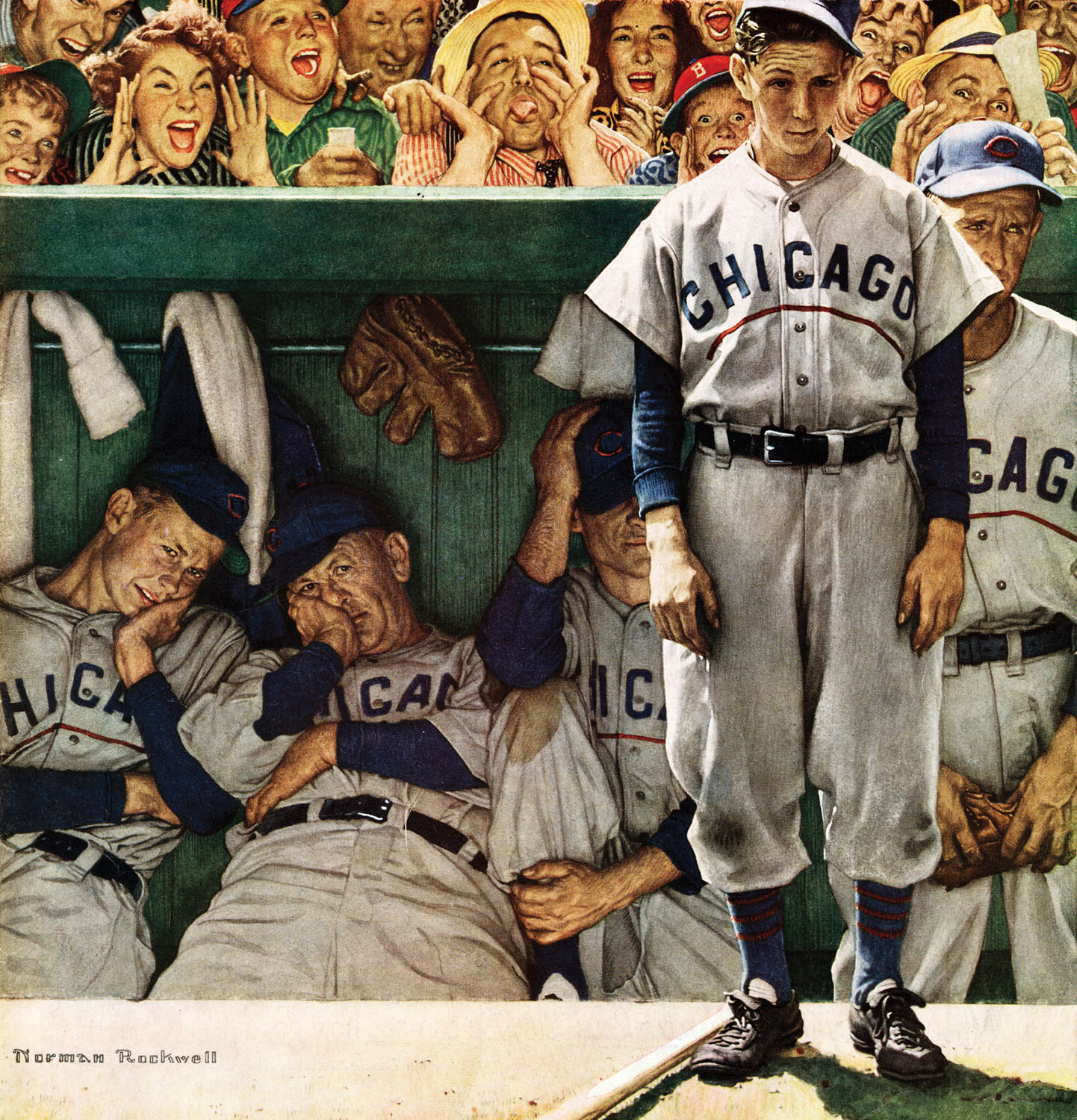

Bean Balls and Broken Windows

By Christopher E. Crowe (BA ’76), Professor of English

The Dugout, 1948.

A boy in a dugout—disappointed, filled with dread. The image takes me back to when dread and disappointment became my companions, sidling up alongside me just after second grade.

Of course, I had experienced them well before I knew their names. I attended Catholic school, after all, and Sister Margaret’s weekly ritual of making us line up in front of the class, hands extended so she could inspect—and critique—our fingernails, always filled me with dread and disappointment.

But dread, disappointment, and I were formally introduced in the scrubby backyard of our two-story stucco house in Bloomington, Ill. When I was in kindergarten and first grade, still a little kid, I’d watch my older brothers, Mike and Bill, play catch in the backyard, one of the most warmly fraternal activities I’d ever seen. I longed to join them, but they’d point out the obvious: I was too little, and, well, I didn’t have a mitt of my own.

“After dinner that night, not only was I a young man who had graduated from the rigors of second grade, but I also possessed my very own mitt. “

That changed on June 13, 1962, when Mike got a new baseball mitt for his birthday, a gift that dominoed his mitt to Bill and Bill’s to me. After dinner that night, not only was I a young man who had graduated from the rigors of second grade, but I also possessed my very own mitt.

Mike and Bill warmed up with a game of pepper, and I watched the ball whiz from one brother to the other until Mike grinned at Bill and said to me, “Okay, Chris, your turn.”

I stood 20 paces from Bill, excited to be initiated into this baseball brotherhood. “Ready?” he asked. I nodded, and he lobbed an underhand toss to me. The ball landed neatly in my mitt, and I threw it back. After a few more lobs, he started throwing overhand. The speed startled me, and I used my mitt to deflect the ball to the ground. I picked it up, threw it back, and Bill fired another one. And another. And another. I swatted fireballs away from my head and chest, and that only encouraged him to add more pepper to each throw. I wanted to drop my mitt and run, but my young machismo overruled my sense of self-preservation.

Just as I was about to quit, Dad showed up on the back porch to watch his boys enjoying America’s national pastime. I made a brave show of trying to handle Bill’s rockets, but every one I tried to catch ricocheted off my mitt and into the dirt. I did catch the look on Dad’s face, an awkward smile that signaled disappointment in my dread.

“Stand in there, Chris,” he said. “You can’t close your eyes and expect to catch anything.”

But I was tired and scared and sore, so I just dodged the next pitch. The ball zinged past me and skipped across the yard and through the stand of bushes that separated our house from Mr. Murdock’s.

Ever since then, baseball and the sound of glass shattering bring back dread and disappointment like nothing else.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.