SCOWCROFT CENTER FOR STRATEGY AND SECURITY

May 2023

SCOWCROFT CENTER FOR STRATEGY AND SECURITY

May 2023

The Atlantic Council Strategy Papers series is the Atlantic Council’s flagship outlet for publishing high-level, strategic thinking. The papers are authored by leading authorities, including a range of established and emerging strategic thinkers from within and outside the Atlantic Council.

n October 2019, the Atlantic Council published Present at the Re-Creation: A Global Strategy for Revitalizing, Adapting, and Defending a Rules-Based International System. This bold paper proposed a comprehensive strategy for rebuilding and strengthening a rules-based order for the current era. in July 2020, the Council published A Global Strategy for Shaping the Post-COVID-19 World, outlining a plan for leading states to recover from the health and economic crisis, and also to seize the crisis as an opportunity to build back better and rejuvenate the global system.

To build upon these far-reaching strategies, the Atlantic Council publishes an annual Global Strategy paper in the Atlantic Council Strategy Papers series. The annual Global Strategy provides recommendations for how the United States and its allies and partners can strengthen the global order, with an eye toward revitalizing, adapting, and defending a rules-based international system. A good strategy is enduring, and the authors expect that many elements of these Global Strategy papers will be constant over the years. At the same time, the world is changing rapidly (perhaps faster than ever before), and these papers take into account the new challenges and opportunities presented by changing circumstances.

Developing a good strategy begins with the end in mind. As General Scowcroft said, a strategy is a statement of one’s goals and a story about how to achieve them. The primary end of all Global Strategy papers will be a strengthened global system that provides likeminded allies and partners with continued peace, prosperity, and freedom.

ATLANTiC COUNC L STRATEGY PAPERS

Executive Editors

Mr. Frederick Kempe

Dr. Alexander V. Mirtchev

Editor-in-Chief

Dr. Matthew Kroenig

Editorial Board Members

Gen. James L. Jones

Mr. Odeh Aburdence

Amb. Paula Dobriansky

Mr. Stephen J. Hadley

Ms. Jane Holl Lute

Ms. Ginny Mulberger

The Hon. Stephanie Murphy

Mr. Dan Poneman

Gen. Arnold Punaro

The Scowcroft Center is grateful to Mr. Frederick Kempe and Dr. Alexander V. Mirtchev for their ongoing support of the Atlantic Council Strategy Papers Series in their capacity as executive editors.

Copyright:

© 2023 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to:

Atlantic Council

1030 15th Street, NW, 12th Floor, Washington, DC 20005

COVER: Dan Engelke, “The Last Day; Black Earth and Red Sky” https://danengelke.com/ installations/

For more information, please visit www.AtlanticCouncil.org

ISBN: 978-1-61977-306-6

Global Foresight 2023 is the second edition of an annual foresight series produced by the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. As was the case with the inaugural edition, the goal of Global Foresight 2023 is to provide a provocative take on how the world might unfold in the years to come. Released by the Atlantic Council as digital products in December 2022 and January 2023, this release gathers those initial products into a formal document.

Global Foresight 2023 contains three main pieces. in the first piece, the Atlantic Council’s sixteen senior directors offer their forecasts of what 2023 might bring, for better and for worse. Their top 23 risks and opportunities in 2023 include iran becoming a nuclear state, Ukraine losing its war with Russia, a “terrorist bridge” forming across the Sahel, the European Union acting as a great power, a doubling of global funding for climate change, and more. The second piece provides survey findings of 167 leading global strategists and foresight practitioners, who provide insights about what might happen in the world by 2033 (an Appendix provides raw survey data). The third piece identifies six “snow leopards,” under-the-radar phenomena that might have unexpected yet critically important impacts in 2023 and beyond. The six snow leopards focus on algorithms, decoupling with China, labor movements, electric vehicles, geoengineering, and East Asian geopolitics.

As the 2022 version of this document also stressed, making sense of our complex world requires that we emphasize the connections across diverse phenomena. As we stated then, such an approach characterizes the field of strategic foresight.

As an Atlantic Council Strategy Paper, Global Foresight 2023 is part of a longstanding series of intellectually robust assessments of the United States, its allies and partners, and the broader world. We hope that the reader finds this second edition of the Global Foresight series to be even more valuable than the first.

Dr. Peter Engelke Deputy Director and Senior Fellow for Foresight Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security Atlantic CouncilGlobal Foresight 2023 was originally published on the Atlantic Council’s website in late 2022 and early 2023, ahead of the release of this PDF version in May 2023. Some of the scenarios envisioned in report therefore may have already begun to unfold or events may have played out differently than the authors expected.

One of the most surprising takeaways was how many respondents pointed to a potential Russian collapse over the next decade—suggesting that the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine could precipitate hugely consequential upheaval in a great power with the largest nuclear-weapons arsenal on the planet.

Nearly half (46 percent) of respondents expect Russia to either become a failed state or break up by 2033. More than a fifth (21 percent) consider Russia the most likely country to become a failed state within the next ten years, which is more than twice the percentage for the next most common choice, Afghanistan.

Even more striking, 40 percent of respondents expect Russia to break up internally by 2033 because of revolution, civil war, political disintegration, or some other reason. Europeans are particularly pessimistic about Russia breaking up: Forty-nine percent of them foresee such an event, compared with 36 percent of Americans.

By 2033, do you expect any of the following countries to break up internally for reasons including but not limited to revolution, civil war, or political disintegration?

Prepare for Russia’s coming crack-up. Plan for a Chinese military assault on Taiwan. Temper the optimism about peak carbon emissions. Brace for the further spread of nuclear weapons. Buckle in for even greater global volatility ahead.

These are just some of the forecasts that emerged this past fall when the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security surveyed the future, asking leading global strategists and foresight practitioners around the world to answer our most burning questions about the biggest drivers of change over the next ten years.

A total of 167 experts shared their insights on what geopolitics, climate change, technological disruption, the global economy, social and political movements, and other domains could look like a decade from now. Although respondents are largely citizens of the United States (roughly 60 percent of those polled), their nationalities are spread across thirty countries, with European citizens constituting the majority of non-Americans. (in the following analysis, all geographic distinctions among those surveyed are based on what individuals identified as their sole or primary nationality, not on the countries where they currently reside.)

Respondents are also employed in a range of fields, including the private sector (26 percent), academic or educational institutions (21 percent), non-profits (19 percent), government (16 percent), and independent consultants or freelancers (13 percent). They are quite evenly distributed across age categories over thirty-five, with less than 10 percent between the ages of twenty-two and thirty-five, but they skew heavily male (a result that we will aim to rectify in future surveys).

So what will the world look like in 2033? Here are the ten biggest findings from the survey.

Note: 149 respondents answered this question

Which country that is not currently a failed state is most likely to become a failed state within the next ten years?

This puts another finding into a darker context: Fourteen percent of respondents believe that Russia is likely to use a nuclear weapon within the next ten years. Among those expecting the country to experience both state failure and a breakup in the coming decade, a sobering 22 percent believe that use of nuclear weapons will be part of that history ten years hence.

Some, though, see hope: Of those who believe Russia is likely to experience state failure or a breakup over the coming decade, 10 percent think that it is the most likely of any currently autocratic country to become democratic by the end of this period.

Barely one in eight respondents (13 percent) stated that no additional country will obtain nuclear weapons in the coming decade, and more than three-quarters named a specific country that they expected to become a nuclear-weapons state during this period. iran was most often cited as a likely nuclear-armed state by 2033 (68 percent of respondents)—an outcome that the Atlantic Council’s Matthew Kroenig, in a separate assessment, argues is highly likely to occur as soon as this coming year. But iran may not be alone. Respondents who expect some expansion of the nuclear-weapons club believe, on average, that 1.6 countries will join within the next ten years.

Note: 147 respondents answered this question Respondents were able to make more than one selection

One reason for this anticipation of multiple new nuclear-armed countries could be that experts expect regional rivalries to drive nuclear proliferation over the next decade. For example, of those who believe that ran will obtain nuclear weapons during this timeframe, 41 percent say Saudi Arabia will as well. n contrast, of those who do not believe that iran will acquire these weapons, just 15 percent envision Saudi Arabia doing so anyway. Similarly, 57 percent of those who say that Japan will acquire nuclear weapons believe the same of South Korea. The former is almost certainly a function of Saudi-iranian antagonism (wherein if one gets the bomb, the other will feel pressure to follow suit); the latter is likely less a function of Japanese-South Korean tension than of both countries feeling increasingly threatened by China and/or North Korea. indeed, among those who foresee China initiating military action to retake Taiwan in the next decade (discussed in more detail below), 22 percent think that South Korea will obtain nuclear weapons over the same period while 16 percent believe Japan will. Among those who foresee no such Chinese use of force, the equivalent figures are 13 percent and 6 percent.

On the positive side, a majority of those polled (58 percent) believe that nuclear weapons will remain unused over the next ten years. On the negative side, it’s nevertheless quite disturbing that nearly a third of respondents (31 percent) expect the next decade to include the first use of nuclear weapons since World War ii. Responses from those who foresee nuclear use suggest that the weapons may be deployed in a regional rather than global conflict. Russia is most frequently cited (14 percent of all respondents) as likely to use such a weapon by 2033. But, of those who expect the country to do so, only one-third believe Russia will fight a war with NATO during this period. The second-most-cited potential perpetrator, North Korea (10 percent), presumably would also initially deploy nuclear weapons regionally against neighbors without nuclear weapons rather than, say, a country with superior nuclear capabilities such as the United States.

Which actor(s), if any, do you expect to use a nuclear weapon within the next ten years?

Many people are currently focused on the risk of Russia engaging in a direct fight with the United States and NATO. But notably, even in the throes of a hot war in Ukraine right on NATO’s borders, the majority of respondents (more than 60 percent) disagreed with the notion that there will be such a Russia-NATO military clash within the next ten years—perhaps suggesting a belief that the conflict in Ukraine can be contained to that country or that the war has exposed Russia as too weak to take the fight directly to NATO. Given that a Chinese military assault on Taiwan would likely prompt the United States to intervene in support of the island, and that respondents were far more inclined to see a China-Taiwan conflict as probable than a Russia-NATO conflict, the biggest impending risk of war between great powers might be in Asia, not Europe.

Do you agree with the following statement? Within the next ten years, Russia and NATO will engage in a direct military conflict.

149 respondents answered this question

Note: 149 respondents answered this question

Respondents were able to make more than one selection

The proliferation of nuclear weapons is consistent with respondent answers that predict a lack of international attention to this issue. Less than 2 percent of respondents named nuclear nonproliferation as the area likely to see the greatest increase in international cooperation over the coming decade. When given the chance to name the biggest global risks receiving insufficient attention, 10 percent mentioned either proliferation or war involving nuclear weapons or weapons of mass destruction.

Recently, US officials have been warning that China could launch a military campaign to reunify Taiwan with the mainland on a faster-than-anticipated schedule between now and 2027. And our survey results support that dire assessment. Fully 70 percent of respondents agree—though just 12 percent strongly agree—that China will seek to forcibly retake Taiwan within the next ten years. Only around two in ten don’t believe that such a scenario will occur. intriguingly, among government employees, the figures rise to near certainty: Eighty-eight percent agree that China will use force against Taiwan, just 8 percent disagree, and the remaining 4 percent do not know.

Do you agree with the following statement? Within the next ten years, Russia and NATO will engage in a direct military conflict.

There has been a lot of talk about “decoupling,” or efforts to disentangle the US and Chinese economies. But the experts we surveyed delivered a clear verdict: Full-blown decoupling is very unlikely. Despite all the geopolitical tensions and tit-for-tat trade restrictions between the two countries, the most likely outcome (according to roughly 40 percent of respondents) is that the US and Chinese economies will be “somewhat less” interdependent in 2033 than they are today. Moreover, of those who believe China will use force against Taiwan, 64 percent predict at least some decline in economic interdependence—a surprisingly low number given how drastic a move a Chinese military campaign against Taiwan would be. Fully 22 percent of those expecting Chinese use of force against Taiwan believe that the US and Chinese economies will become more interdependent by 2033.

In 2033, will the economies of the United States and China be more or less interdependent than they are today?

Note: 149 respondents answered this question

1 Mallory Shelbourne, “China’s Accelerated Timeline to Take Taiwan Pushing Navy in the Pacific, Says CNO Gilday,” USNI News, October 19, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/10/19/chinas-accelerated-timeline-to-take-taiwan-pushing-navy-in-the-pacific-says-cno-gilday

Note: 148 respondents answered this question

Overall, 58 percent of respondents forecast less economic interdependence between the two countries by 2033 and just 23 percent expect more. US respondents are slightly more convinced about this direction of travel, with 64 percent anticipating a drop in interdependence (24 percent still anticipate an increase).

Just as important, though, roughly eight in ten respondents—both overall and among Americans—expect any change in either direction to be limited at most. The widespread expectation, then, is a slow decoupling.

Respondents generally expressed a belief in the United States’ staying power over the next ten years, though many envisioned a country preeminent in some domains of national clout but not others. Seven in ten foresee the United States continuing to be the world’s dominant military power by 2033—a notably high percentage given concerns about China’s military modernization and the United States losing its military edge—while about half think the United States will maintain its technological dominance over everyone else. Just three in ten, however, believe the United States will be the world’s dominant player in diplomacy, and only slightly more than three in ten believe it will be the world’s dominant economic power.

All of which raises a question: if the United States loses its economic and diplomatic dominance, can its other advantages be maintained? After all, military power depends to a substantial degree on strong alliances and economic and technological prowess, while technological power relies in large part on a country’s capacity to commercialize technological advances.

By 2033, in which of the following will the United States be the world’s dominant power?

Climate change is the issue most likely to shoot up the international policy agenda in the coming decade, according to respondents. A plurality (42 percent) believe that it will garner the biggest increase in international collaboration, comfortably ahead of second-place public health (cited by 25 percent of those polled).

In which of the following fields do you expect the greatest expansion of global cooperation over the next ten years?

Two minority groups of respondents have sharply divergent views about American power. The first group, constituting 19 percent of the survey pool, are pessimists, believing one or more of the following will be true by 2033: The United States will be a failed state; it will have broken apart; or it will no longer be the world’s dominant power in any category our survey covered: military, economic, diplomatic, or technological. (Notably, roughly the same proportion of respondents—7 percent—listed the United States and Pakistan as the country most likely to fail over the next ten years.) Fourteen percent of American respondents and 17 percent of European respondents fall into this group. The most striking answers are from those who are citizens of countries outside the United States and Europe: Over half of these are in our pessimists category. (This analysis does not treat them generally as a category because they are too diverse to characterize and too few to rely on statistically.)

The second group, constituting 12 percent of all respondents, are optimists, believing that the United States will be the single dominant power in all fields: military, economic, diplomatic, and technological. Among American and European respondents, the proportions of optimists—12 percent and 15 percent respectively—are roughly the same as those for pessimists. The big difference comes from the rest of the world, where no respondents expect the United States to have such multifaceted hegemony by 2033.

Note: 151 respondents answered this question

Of those who assert that climate issues will attract the biggest boost in global cooperation by 2033, nearly a third (29 percent) believe that, among various social movements presented to respondents, environmental movements will have the most political influence worldwide over the next ten years. Among those who do not think climate change will rise up the international agenda, only 12 percent expect environmental movements to wield such influence.

f political leaders and policymakers focus more on climate issues, will greenhouse-gas emissions peak and start to decline over the next ten years? Views are mixed. The nternational Energy Agency (iEA) recently estimated2 that global carbon-dioxide emissions will peak in 2025 (although it also admitted3 that a significant gap remains between countries’ stated emissions goals and the target of stabilizing the average rise in global temperature at 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels). Respondents who foresee greater global cooperation to address climate change are split on peak emissions, in a reminder that such collaboration could result from both a proactive effort to accelerate the clean-energy transition or a more reactive response to a still-rapidly warming world: 47 percent believe that the peak will have occurred by 2033, but 42 percent disagree. Among the others, the equivalent figures—26 percent and 60 percent—reveal much greater pessimism.

Overall, in a clear counterpoint to the iEA’s assessment, a majority of respondents don’t think greenhouse-gas emissions will have peaked and begun to decline by 2033. The experts we polled are only a bit more bullish about that peak and decline happening within the next decade (35 percent) as they are about humans safely landing on Mars and returning to Earth during that period (23 percent). Only 6 percent strongly agree that we’ll see emissions peaking and declining over the next ten years.

2 nternational Energy Agency, “World Energy Outlook 2022 shows the global energy crisis can be a historic turning point towards a cleaner and more secure future,” nternational Energy Agency, October 27, 2022, https://www.iea.org/news/world-energy-outlook-2022-shows-the-globalenergy-crisis-can-be-a-historic-turning-point-towards-a-cleaner-and-more-secure-future

3 nternational Energy Agency, “Executive Summary,” World Energy Outlook 2022, November 2022, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energyoutlook-2022/executive-summary

Do you agree with the following statement? By 2033, global greenhouse-gas emissions will have peaked and begun to decline by 2033.

between 1908 and 1946, five global recessions brought about greater declines5 in global per-capita gross domestic product than did the 2008-2009 crisis—amounting to more than one per decade.

On a separate question, respondents on balance were also more inclined to agree (39 percent) than disagree (35 percent) that by 2033 humans likely will have begun deliberate, large-scale geoengineering of the planet (for example, seeding the atmosphere with aerosols) in order to reduce the impacts of climate change—indicating that a slight plurality presumably think those climate impacts will be big enough by that point to spur such a controversial and consequential move.

Do you agree with the following statement? By 2033, humans will have begun deliberate, largescale geoengineering of the planet in order to reduce the impacts of climate change.

One remarkable survey result is how many respondents expect the world to face additional economic and public-health perils in the coming decade. Seventy-six percent predict another global economic crisis on the scale of the 2008-2009 financial crisis by 2033. A further 19 percent say that there will be two or more such crises. Forty-nine percent foresee another global pandemic with the scale and impact of COV D-19 breaking out by 2033, with an additional 16 percent anticipating two or more such pandemics.

How many of the following do you expect the world to have experienced by 2033?

Our respondents as a whole do not foresee a clear triumph for either democrats or autocrats over the next ten years. More expect the number of democracies in the world to shrink (37 percent) than to grow (29 percent). But almost all forecast any change to be modest: Just 4 percent foresee many more or many fewer democracies by 2033. Thirty-five percent believe the world will have roughly the same number of democracies as it does today. ( t’s worth noting that we asked about the future number of democracies, not the projected strength or type of these democracies.)

Which statement best describes what you expect the state of global democracy to be ten years from now?

The world will have a few fewer democracies

The world will have roughly the same number of democracies that it does today

The world will have a few more democracies

The world will have many more democracies

The world will have many fewer democracies

Note: 145 respondents answered this question

When asked open-ended questions about which countries are most likely to move from democracy to autocracy or the reverse by 2033, respondents most frequently chose “none.” Notably, 46 percent foresaw no shifts from autocracy toward democracy and just 31 percent predicted no countries going in the other direction, which is consistent with respondents’ general view that overall change will be modest but trending away from democracy.

Democracy and autocracy, moreover, are not necessarily distinct categories. For example, several countries—including Hungary, Turkey, and Russia—are cited both as autocracies likely to become democracies or democracies likely to become autocracies, suggesting that some respondents have differing views on how to categorize these countries.

These results might reflect recency bias, where recent experience of crises leaves us more concerned about others occurring. But they may also suggest more troubling trends, including a coming era of more frequent and intense public-health emergencies4 rather than once-in-a-century pandemics as well as a return to historical economic patterns after the relative calm of the post-World War ii decades;

4 Marco Marani, Gabriel G. Katul, William K. Pan, and Anthony J. Parolari, “ ntensity and frequency of novel epidemics,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Congress 118, no. 35 (2021): e2105482118, accessed February 10, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2105482118

Which democratic country today is most likely to become autocratic over the next ten years?

Those answering “none” are excluded.

Which autocratic country today is most likely to become democratic over the next ten years?

Those answering “none” are excluded.

Which types of social movements will have the most political influence worldwide over the next ten years?

Also notable: A small but significant minority of 9 percent of all respondents—and 10 percent of US respondents—selected the United States as the democratic country most likely to grow autocratic by 2033. Some respondents’ views on the future of US and global democracy appear to be linked, suggesting that they see the United States as the most important democratic country and guardian of global democracy. Among those who foresee either no change or a decline in the number of democracies worldwide, 12 percent expect the United States to become autocratic—their top choice. For those who expect the number of democracies to expand, none predict an autocratic United States.

Democracies are entering a dangerous decade in which they will need to contend with nationalist and populist forces and all the challenges associated with rapidly evolving technology. When asked which social movements they expected to have the most political influence worldwide over the next ten years, only 5 percent of respondents chose pro-democracy ones—whereas a majority picked either nationalist or populist movements. A third of respondents went with movements advocating for other causes often associated with democratic societies: the environment, youth issues, and women’s rights.

Note: 143 respondents answered this question

Admittedly, nationalists and populists are not invariably more supportive of autocratic political systems than democratic ones. Nor are, say, youth movements invariably opposed to autocracy. But our survey responses pointed to a connection between gathering nationalist and populist strength and greater popular pressure toward autocracy. Among those who foresee fewer democracies in the next decade, 68 percent predict increasing political influence for populist or nationalist movements and just 2 percent growing clout for pro-democracy ones. Of those forecasting more democracies, the equivalent figures are 38 percent and 10 percent.

Trends in mass communication and new technologies also present potential perils for democracies. Against the backdrop of a tech sector undergoing great transformation—from new regulatory efforts to the corporate upheaval at social-media companies to the ways in which these platforms have been caught up in broader political polarization—over half of respondents (53 percent) predict that social media will prove a net negative for democracies by 2033. Only 15 percent think it will be a net positive—a remarkable shift away from the dream, so prevalent during the early Arab Spring era, of social media as a democratizing force. Eighteen percent say that social media will have so evolved over the next ten years as to make the question impossible to answer.

By 2033, will social media on balance be a net positive or net negative for democracies around the world?

within democratic norms and values through appropriate regulation and standards and via international cooperation.

Through their answers across several questions, respondents raised the prospect of two contrasting scenarios for the coming decade. One of a world with democracy in decline, corroded by nationalism, populism, and social media, with a more autocratic United States deepening the trend. And another— predicted by a minority—of a world where democracy is ascendant, bolstered by a democratic United States, as well as social movements and mass-communication platforms consistent with democratic values.

Note: 143 respondents answered this question

For those who forecast a reduction in the number of democracies around the world, a large share (69 percent) expect social media to be a net negative for democracies.

By 2033, will social media on balance be a net positive or net negative for democracies around the world?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has revealed the capabilities and limits of institutions designed to enhance international security. While our respondents predict a range of major challenges to human security over the next ten years—from conflict over Taiwan to the fragility of the Russian state to more pandemics and economic crises—they expect the world’s existing security architecture to stay mostly the same.

Which of the following best describes the form NATO will have ten years from now?

Note: 148 respondents answered this question

Eighty-two percent of respondents, for example, believe that over the next decade NATO will remain an alliance of North American and European countries based on a mutual security guarantee. Among respondents who are citizens of NATO member states, 85 percent think that the Alliance’s current form will be maintained; among those from other countries, 71 percent say the same.

Responses on the possible expansion of the United Nations Security Council convey a similar message. Sixty-four percent of all respondents expect no new permanent seats to be added to the UN’s most powerful body by 2033. The difference between respondents who are citizens of countries with permanent seats and those who are citizens of countries without permanent seats isn’t pronounced (66 percent and 61 percent, respectively).

Another compelling finding involved optimism about the speed with which some disruptive technologies—specifically commercial quantum computing, level 5 autonomous vehicles (where the vehicle performs all tasks under all driving conditions without the need of human input), and artificial general intelligence (where computers and machines exhibit human-like intelligence and creativity)—will be developed. in all three cases, majorities of respondents (between 57 percent and 68 percent) agree that these technologies will exist and/or be commercially viable by 2033. Although all three technologies promise enormous benefits for humankind, they also will raise challenges related to the future of work and income, public health and safety, national security, and democratic governance, among other domains. Democracies will need to ground the development and implementation of such technologies

10. International security organizations are likely to remain largely unchanged even as the world confronts unprecedented change and challenge

Which countries will receive a new, permanent seat on the UN Security Council within the next ten years?

No new permanent seats will be added

PeterEngelke is on the adjunct faculty at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies and is a frequent lecturer to the US Department of State’s Foreign Service Institute. He was previously an executive-in-residence at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, a Bosch fellow with the Robert Bosch Foundation in Stuttgart, Germany, and a visiting fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington, DC.

Uri Friedman, Managing Editor, Atlantic CouncilFriedman is also a contributing writer at The Atlantic, where he writes a regular column on international affairs. He was previously a senior staff writer at The Atlantic covering national security and global affairs, the editor of The Atlantic’s Global section, and the deputy managing editor of Foreign Policy magazine.

Note: 149 respondents answered this question Respondents were able to make more than one selection

Beyond institutional inertia and the self-interest of the Council’s current permanent members, a major challenge in expanding the Security Council is the complexity of doing so. As one respondent told us, “if additional seats are added, it will be more than one because the rest of the world will not come [together] around a single candidate.” As a group, those surveyed seem to agree: Respondents who predict Security Council expansion identify an average of 1.7 new members. The strong presumption is that, if the number of permanent seats grows, india will be one of the beneficiaries. Over half of those forecasting that Japan, Brazil, Nigeria, or South Africa will gain a seat also say that india will get one. For those who chose Germany this figure is less than half but still 45 percent. f ndia’s time could soon come, however, Africa’s looks distant: Only 6 percent of respondents mention Nigeria or South Africa as likely new permanent Security Council members within the next ten years.

A question not directly posed to our respondents is whether this forecasted lack of change in NATO and the UN Security Council is indicative of strength (that these organizations will be effective tools amid the coming decade’s challenges) or weakness (that they are unable to adjust even amid manifest need). Some respondents offered comments pointing to the latter possibility. One worries that, without change, the Security Council will lose relevance as an increasing number of decisions about international security are made elsewhere. Meanwhile, 4 percent of respondents noted, unprompted, that they expect NATO will need to take on a wider global remit, including Asian security, over the course of the next decade. These are more whispers in the margins than the expression of a common opinion, but they do raise questions about whether stasis in these institutions should be interpreted as a sign of institutional health.

Mary Kate Aylward, Publications Editor, Atlantic Council

Aylward was an editor at War on the Rocks and Army AL&T before joining the Council. She was previously a junior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Paul Kielstra, Freelance Analyst

Kielstra is a freelance author who has published extensively in fields including business analysis, healthcare, energy policy, fraud control, international trade, and international relations. His work regularly includes the drafting and analysis of large surveys, along with desk research, expert interviews, and scenario building. His clients have included the Atlantic Council, the Economist Group, the Financial Times Group, the World Health Organization, and Kroll. Kielstra holds a doctorate in modern history from the University of Oxford, a graduate diploma in economics from the London School of Economics, and a bachelor of arts from the University of Toronto. He is also a published historian.

Another world-shaking, world-reordering war in Europe. Brewing fears of war on an even greater scale in Asia. A coronation in China and political upheaval across the democratic world. Climate-induced catastrophes and emboldened movements to mitigate and adapt to them. The worst energy crisis in a half century and worst food crisis in over a decade. Spiraling inflation and the specter of global recession. A less acute but still-raging, still-hugely disruptive pandemic. Epochal ferment in social media and technology more broadly.

Recently, the leaders of the Atlantic Council’s sixteen programs and centers gathered to take stock of these and other developments and trends over the past year, peer into the future, and predict the biggest global risks and opportunities that 2023 could bring.

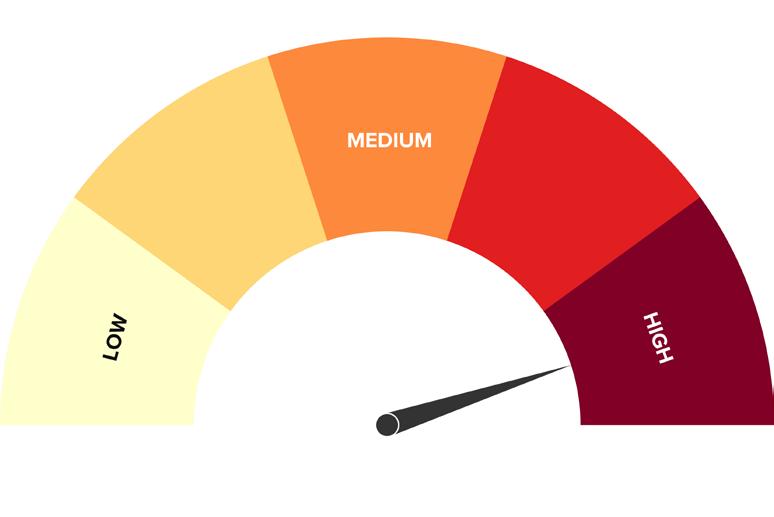

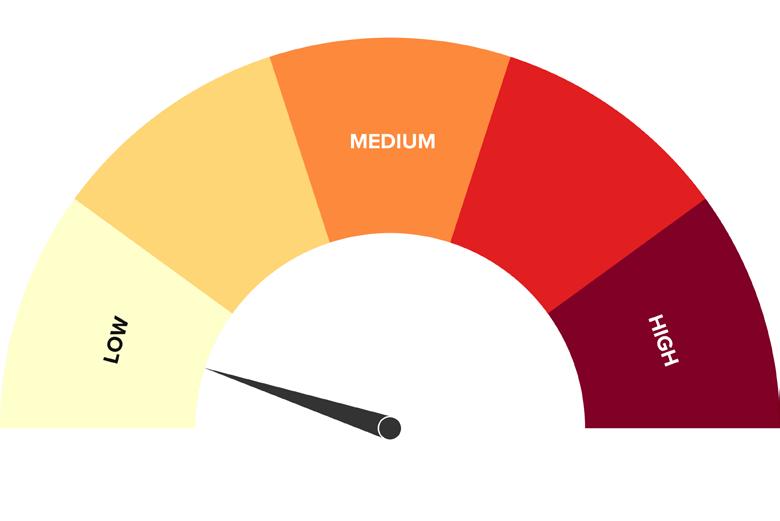

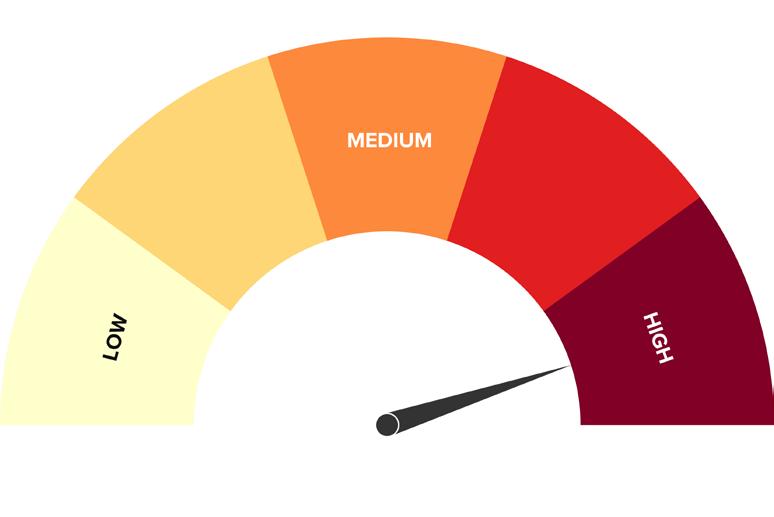

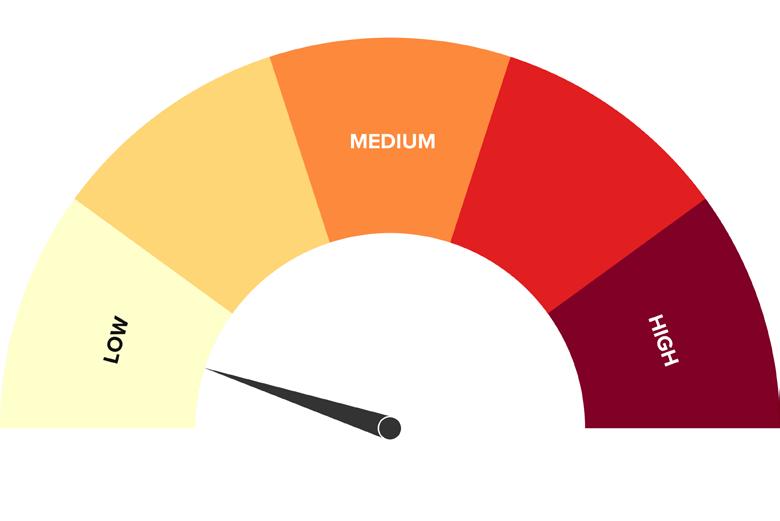

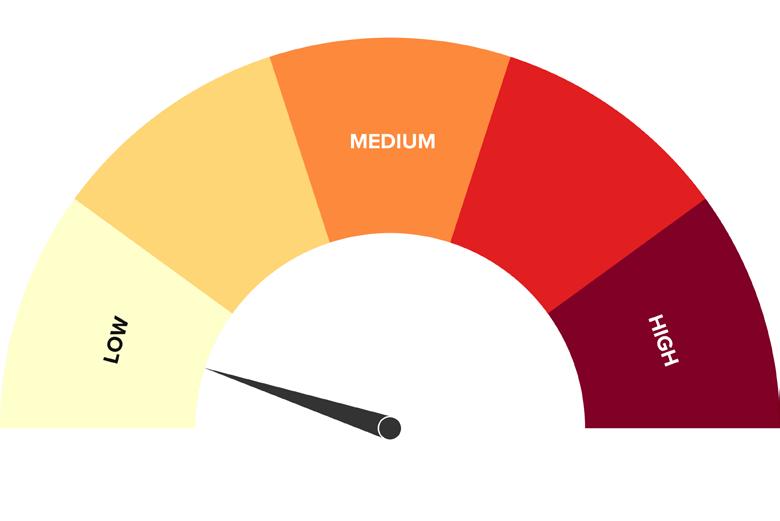

The results of this foresight exercise are below. Each scenario is assigned a probability; “medium” means a 50/50 chance that the scenario will occur within the next year. Many lower-probability but highly consequential scenarios are included because—as has been so vividly demonstrated this past year—those types of events tend to be some of the most disruptive and transformative. And keep in mind: Forecasts are not destiny. Political leaders and policymakers have agency in shaping whether and how these scenarios play out in the coming year or beyond. The primary purpose of assessing global risks and opportunities, in fact, is to gain insight into how to avert unwanted outcomes and achieve desired ones. To that end, don’t miss the policy prescriptions mixed into many of the entries below.

This article was originally published on the Atlantic Council’s website in January 2023, and some of the risks and opportunities outlined here may have already begun to unfold.

Pakistan’s devastating floods in 2022, along with the tireless advocacy of Pakistan’s federal minister for climate change, Sherry Rehman, played a pivotal role in rallying parties at the COP27 climate conference to create a Loss and Damage Fund, where rich countries will provide payments to developing countries confronting the costly impacts of climate change.

But there is a strong possibility in the coming year that this new and desperately needed focus on climate resilience, loss, and damage will produce an unintended opportunity for backsliding on mitigating climate change. Moving from the COP27 agreement to an actual fund with money and a plan to disburse it will require tremendous international activism and action, which could reduce the pressure on governments and non-state actors to cut greenhouse-gas emissions and transition to clean energy. That would slow the already sluggish speed at which the world reins in global warming—the root cause of the destruction that has necessitated the Loss and Damage Fund in the first place. f country and corporate delegates show up in December at the COP28 climate-change conference in the United Arab Emirates with a focus on climate adaptation and loss and damage, but without major commitments to reduce emissions as well, we’ll know this scenario has materialized—and that this century the world will blow past an average increase in temperatures of 1.5 degrees Celsius6 above pre-industrial levels, which countries have sought to avoid as part of their commitments at the 2015 Paris climate conference.

Baughman McLeod was a global environmental and social risk executive at Bank of America, and a former managing director of climate risk and resilience at The Nature Conservancy. She was an energy and climate commissioner of the state of Florida.

in 2023, ran is very likely to pass the point of no return and become a de facto nuclear-weapons state. Outside experts estimate that iran’s dash time (the time it would take to make one bomb’s worth of weapons-grade uranium) has shrunk to just a few weeks. As iran continues to ramp up7 its nuclear program, this timeline will soon shrink to zero.

With international nuclear talks stalled amid continuing protests inside iran at the end of 2022, a diplomatic breakthrough to halt the program now seems implausible. Several consecutive US presidents, including Joe Biden, have said that the use of force is a last-resort option to keep Tehran from the bomb, but many suspect a bluff. Washington is not taking the steps (such as building domestic or international support for military action) that would be the obvious prelude to military strikes on iran’s nuclear facilities. iran is unlikely to test a nuclear explosive device in 2023—and it will take time (perhaps years) for it to put a warhead on a ballistic missile. But once iran has enough weapons-grade material for its first bomb, the game is over. We will look back at 2023 as the year in which the bipartisan US and international effort to keep Tehran from the bomb failed.

Matthew Kroenig, Acting Director, Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security

Kroenig currently sits on the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States. He served in defense and intelligence roles in the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations. From 2017 to 2021, he was a senior policy adviser to the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capability/Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy.

Liberation Army guerrilla group, and move away from lockstep coordination with the United States on eradicating drugs and overall drug policy (a joint approach that has been the fundamental tenet of USColombia relations over the last twenty years). Fallout in the United States, could, in turn, offer China an opportunity to increase its clout in Colombia. More broadly, inflation and other economic woes in the United States could have outsize consequences for Latin American countries, including greater political polarization and social unrest that leads to democratic backsliding as well as sovereign-debt issues. China could then position itself as a provider of desperately needed relief for countries grappling with these challenges. in such a scenario, US policymakers might be at risk of increasingly losing influence in not just Colombia but Latin America as a whole. A secure position in its near abroad has long been a predicate for America’s robust global posture. is that position now poised to further erode, even with a longstanding ally?

Jason Marczak, Senior Director, Adrienne Arsht Latin American CenterMarczak has over twenty years of expertise in Latin American economics, politics, and development, working with policymakers and private-sector executives to shape public policy. He is an adjunct professor at the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs where he teaches on Central America and US immigration policy.

Colombia has long served as the linchpin of US policy in Latin America, and it is currently the only major economy in South America that does not have8 China as its largest trading partner. But all that may be set to change in 2023. in pursuing his policy agenda, the country’s new president, Gustavo Petro, could generate a backlash in the US Congress, particularly the Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

Those policies include Petro’s efforts to reimagine (and potentially scale back) cooperation with Washington on judicial issues and criminal extradition, achieve a possible agreement with Colombia’s National

7 Stephanie Liechtenstein, “U.N. agency: iran continues to block nuclear probe, scales up its nuclear program,” Politico, November 10, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/11/10/un-agency-iran-nuclear-probe-00066350

8 “Columbia Trade,” World ntegrated Trade Solution, accessed February 10, 2023, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountrySnapshot/en/COL

Authoritarians have been trying to assert control over their technology ecosystems for years, but 2023 could be the year they finally succeed in creating online information environments that they can fully command. Russia, for example, has increased efforts to censor or shut down entire digital platforms for allowing any information about its war of aggression against Ukraine, turning these platforms into a new domain of conflict. China is going further and seeking to build the backbone of an unfree internet beyond its borders9 by investing in information infrastructure as part of its “discourse power”10 strategy. Even some democracies such as india11 and Turkey12 are instituting sweeping internet shutdowns and crackdowns on freedom of expression online. The US government, meanwhile, lacks a clearly articulated strategy to promote an alternative at home and abroad. What’s playing out is not a partitioning of the infrastructure on which the internet operates, but rather an intensifying contest over the rules that govern infrastructure that is inherently interconnected.

Don’t expect a switch to flip, but watch for a slow roll toward two internets: one designed to facilitate government control with built-in surveillance, and one at least aiming to be free, open, secure, interoperable, and governed by many. There is a low likelihood that a full-scale splintering happens in the coming year. But if it does, it would change the world for a long time to come—and it could have a catalytic impact on nearly every other risk and opportunity on this list. There is opportunity embedded

9 Kenton Thibaut, China’s discourse power operations in the Global South, Atlantic Council, April 20, 2022 https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/indepth-research-reports/report/chinas-discourse-power-operations-in-the-global-south/

10 Kenton Thibaut, Chinese discourse power: Ambitions and reality in the digital domain, Atlantic Council, August 24, 2022, https://www. atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/chinese-discourse-power-ambitions-and-reality-in-the-digital-domain/

11 “ ndia: Freedom on the Net 2022,” Freedom House, accessed February 10, 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/country/india/freedom-net/2022

12 “Turkey: Freedom on the Net 2022,” Freedom House, accessed February 10, 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkey/freedomnet/2022

The United States loses Colombia—and with it, increasingly, Latin America

in this risk, however: Through novel mechanisms such as the Freedom Online Coalition,13 the US-EU Trade and Technology Council, a new US State Department bureau focused on digital freedom (the Bureau for Cyberspace and Digital Policy), and new offices at the US National Security Council, democratic countries are now better staffed and resourced to craft that much-needed strategy for protecting an open, global internet. There is nothing inevitable about a “splinternet.”14

GrahamBrookie served in various positions at the White House and National Security Council. His most recent role was as an adviser for strategic communications with a focus on digital strategy, audience engagement, and coordinating a cohesive record of former US President Barack Obama’s national security and foreign policy.

As long as US leadership remains strong, Russian President Vladimir Putin will lose in Ukraine. But a Russian victory could come if the United States forgets its vital interests in this outcome. There are several ways in which such a scenario—whose probability i’d put at under 10 percent—could materialize.

One possibility: in response to Putin’s continued nuclear saber-rattling, fear of nuclear war (fear that would likely be ill-considered, i believe) grows to such an extent in the United States that the country ends up substantially reducing aid to Ukraine. if populist right-wing politicians, despite their underperformance in the US midterm elections, gain greater influence in Washington, that could also lead to a reduction in such assistance. Higher energy prices in the United States and especially in Europe could pressure governments as well.

John Herbst, Senior Director, EurasiaHerbst’s 31-year career in the US Foreign Service included time as US ambassador to Uzbekistan, other service in and with post-Soviet states, and his appointment as US ambassador to Ukraine from 2003 to 2006. In that role he helped ensure the conduct of a fair Ukrainian presidential election and prevent violence during the Orange Revolution.

Putin is playing the long game with Europe—and he can still win. Thus far we’ve seen unprecedented, underappreciated European cohesion in response to Russia’s war against Ukraine, but that unity can’t be taken for granted. And we’re already seeing cracks in familiar places, including between large and small countries as we ll as wealthy and poorer ones. There are four drivers of this risk, which taken together could produce political gridlock and fragmentation in the European Union (EU). The losers in such an outcome? Europe, Ukraine, and the transatlantic relationship. The Winner? Putin.

13 Rose Jackson, Leah Fiddler, and Jacqueline Malaret, An introduction to the Freedom Online Coalition, Atlantic Council, December 6, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/introduction-freedom-online-coalition/

14 Nathaniel Fick, Jami Miscik, Adam Segal, and Gordon M. Goldstein, Confronting Reality in Cyberspace: Foreign Policy for a Fragmented Internet, Council on Foreign Relations, July 2022, https://www.cfr.org/report/confronting-reality-in-cyberspace

Energy shocks: The coming year’s energy crisis could be worse than this past year’s. With Russian gas flows no longer available to refill depleted European stocks early in 2023 and no significant new European import capacity coming online, prices in the region could stay elevated and produce a mad scramble for gas.

Economic contraction: The economic ripple effects of gas shortages include the risk of recession, inflationary pressures, business failures, and all the attendant impacts on cost of living, living standards, and labor markets, which in turn have political repercussions. in the medium term, these consequences might do lasting damage to European competitiveness. We’re already seeing trade surpluses dwindling and key economic sectors idling production.

The toxic brew of #1 and #2: The stabilization measures that European governments have put in place to respond to the two challenges above could fuel concerns about sovereign debt and lead to a new Eurozone crisis.

Domestic dynamics: The Franco-German engine of European action is sputtering. Economic problems, French President Emmanuel Macron’s precarious parliamentary backing, and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s complicated three-party coalition constrain both countries’ leaders at home and in the region, and there is uncertainty about how italy’s new right-wing, EU-skeptical government will relate to Brussels. Major elections in 2023 in Poland, Greece, Estonia, Finland, Spain, and other countries could bring Euroskeptic and Russia-sympathetic politicians to the fore— while also pushing existing governments in those directions.

Fleck was chief of staff for a member of the European Parliament and then director of the Transatlantic Policy Network. At the Atlantic Council he continues his work liaising with US and EU lawmakers on diplomatic relations, trade policy, and EU foreign and security policy.

The end of 2022 featured the worst global energy crisis since the Arab oil embargo of the 1970s. The crisis is not purely of Russia’s making, though major drivers include the geopolitical uncertainty produced by the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine as well as Russian attempts to weaponize its oil and gas supplies. The decrease in energy demand during the early part of the COViD-19 pandemic aggravated chronic underinvestment in the energy sector. Coupled with a rapidly warming planet, these factors have put affordable and reliable energy resources out of reach for many in both developed and emerging economies. Moreover, price pressure on the conventional energy resources of oil, gas, and coal comes when the world is also experiencing a unique confluence of drought and abnormal weather patterns, which have hobbled access to electricity from nuclear power (in France, for instance, where water scarcity is impacting nuclear-fuel production) and hydropower (in China and previously Argentina and Brazil).

LandonDerentz is the former director of Middle Eastern and African affairs at the US Department of Energy. He served in energy-related roles at the National Security Council and National Economic Council, and under three energy secretaries.

Burkina Faso experienced two coups in 2022 and Mali is still ruled by a military junta that seized power at the end of 2021. The military factions that took control in each country have not yet allowed transitions to democratic elections to take place. The resulting political instability and uncertainty in West Africa compounds the challenges of containing the jihadist movements active in both countries and elsewhere in Africa, with recent attacks in Benin, Cote d’ivoire, and Togo.

These jihadists—linked to al-Qaeda and the islamic State—seek to control a span of territory stretching from the Red Sea to the Atlantic coast of Africa. That would grant them access to drug-trafficking routes from South America, which would provide a substantial source of revenue for their wars. Though great-power competition and conventional warfare are in the global spotlight now, jihadist groups with transnational ambitions, based in weak, unstable states, are a risk that merits attention. With jihadist movements also active elsewhere on the continent—from Mozambique to the Great Lakes—some experts are stressing the risk of an “Africanization of jihadism.”

Rama Yade, Senior Director, Africa Center

Yade served in several positions in the French government, including as the deputy minister for foreign affairs and human rights, and executive director of the France-West Africa Parliamentary Friendship Group. She also teaches African affairs at Mohammed VI Polytechnic University in Morocco and at Sciences Po – Paris.

There are many paths to a major crisis over the Taiwan Strait, the risk of which jumped significantly in the last half of 2022 following China’s military response to US Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan in August. How might it start? it probably won’t be a development in Taiwan itself or some bolt from the blue by the Chinese. i haven’t seen serious signs that China will attempt to force Taiwan to unify with the mainland in the coming year.

One possible spark would be some action by US policymakers in Congress, where momentum in favor of stepped-up US material and rhetorical support for Taiwan’s defense and de facto independence is only likely to grow with the Republican takeover of the House. China’s reaction would likely go well beyond what it did following Pelosi’s visit, which included launching ballistic missiles near Taiwan, carrying out military exercises in the waters around the island, conducting a dry run for a blockade, and canceling diplomatic dialogues with the United States. Whatever the response from Chinese leaders, the result will be a new—and more confrontational—normal. They might, for example, take retaliatory actions in

Taiwan’s offshore islands or launch a cyberattack against Taiwan’s electrical grid. They may carry out measures that affect the Taiwanese economy or regional supply chains—such as a true blockade of the island—and generally make a mess of the global economy as a result. World War iii over Taiwan in 2023 isn’t likely, but what is more likely is a serious Strait standoff short of war that tests US resolve and raises the risk of war in the near future. And any confrontation that pushes the United States and China further into their corners is dangerous in its own right.

David Shullman, Senior Director, Global China Hub

Shullman oversaw the International Republican Institute’s work building the resilience of democratic institutions around the world against the influence of China, Russia, and other autocracies. For nearly a dozen years he was one of the US government’s top experts on East Asia, most recently as deputy national intelligence officer for East Asia on the National Intelligence Council.

Alarmism about the health of the US dollar is an age-old tradition in Washington and beyond. Even a broken clock is right twice a day, though, and that time of day may be approaching. The dollar’s advantages remain deeply entrenched in the global financial system. Americans experiencing the strength of the dollar right now relative to currencies such as the pound, euro, and yen would be forgiven for thinking that there is nothing to worry about.

When you drill down, though, it becomes clear that many countries would like to move away from the dollar even if it won’t be easy and there is no clear alternative15 in the near term. That shift is, in fact, already happening gradually. The dollar’s share of foreign-exchange reserves is declining.16 Nations around the world—not just US rivals such as China but also countries including india, indonesia, Malaysia, and South Africa—are investing in technologies such as central bank digital currencies17 that could make them less reliant on the dollar. The unprecedented global sanctions regime swiftly imposed on Russia in the wake of its February invasion of Ukraine has only increased the likelihood of an accelerated move away from the dollar—perhaps to a probability of roughly 15 percent. if countries can find ways around the dollar, the impact of sanctions would be undercut over time. The next time an adversary violates another country’s borders, the US economic counterpunch might not be quite as painful.

15 Ananya

16

17 Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker, Atlantic Council, accessed February 10, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker/

Despite recurring pressures over the decades for US withdrawal from the Middle East, US interests in the region have remained stable and US and Middle Eastern leaders have repeatedly sought to overcome the challenges that could precipitate such a withdrawal. But my fear is that the stars align for that pattern to finally change in 2023.

in Washington, those advocating for less US action or presence abroad have growing influence in both parties, though to date they have been largely held at bay by the Biden administration. n Riyadh, relations with the United States are increasingly strained, with each side too often publicly expressing unreasonable expectations of the other. in Jerusalem, the most right-wing government in the country’s history is about to take office, bringing with it predictable challenges for the US-israel relationship. in Tehran, the regime continues to extend its malign activities outside the region and violently repress its people, all while the most dangerous internal elements jockey for position amid the looming succession of the supreme leader. in this context, the central policy question that has driven US-iran relations for three consecutive US administrations—should the United States favor or oppose the 2015 nuclear agreement with Tehran—becomes irrelevant. Longstanding regional partners too frequently deprioritize US concerns over China and Russia in an effort to hedge against the prospect of US withdrawal, which only serves to increase the probability of that outcome. Several of these partners are perceived to have taken sides in US partisan politics, which contributes to the trend of US policies shifting along with election results. So the questions must now be asked: Over the course of the coming year, will US and Middle Eastern leaders still recognize a strategic need to prevent US withdrawal from the region? if so, what preferences are they willing to subordinate to that end?

William Wechsler, Senior Director, Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs

Wechsler’s career in government focused on military, law enforcement, and financial efforts to combat transnational crime networks and terrorist groups. His most recent government position was deputy assistant secretary of defense for special operations and Combatting Terrorism.

The world is moving toward a global recession. That will mean less demand and a lower price for non-energy exports from developing countries. At the same time, the cost of energy and food is rising, in part as a result of the global fallout from the war in Ukraine. Developing countries are therefore about to get squeezed—making less money on what they’re selling and paying more money for what they’re buying. At the same time, interest rates are going up everywhere and lenders are showing less tolerance to assume risk in their dealings with developing countries.

All this will make it harder for developing countries to service and refinance their debt, which will increase the likelihood of sovereign and corporate defaults. Defaults, in turn, could have broader knock-on effects such as stoking authoritarianism and insecurity in politically fragile countries. The poorest countries will fare the worst with these trends in the coming year.

Negrea was the State Department’s special representative for commercial and business affairs from 2019-2021, and he held the economic portfolio in the secretary of state’s Policy Planning office from 2018-2019. He began his career as an official in the Ministry of Finance in Communist Romania, then defected to the United States and went on to a three-decade career on Wall Street.

Many democratic countries are heading into 2023 with highly divided societies, shaky institutions, and question marks hanging over their political leaders. in Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro stoked rumors of voter fraud and rigged elections throughout the country’s 2022 presidential campaign and took his time conceding to Luiz inácio Lula da Silva, who resumes the presidency after spending time in prison on corruption charges. in israel, the fifth election in four years returned Benjamin Netanyahu to power by a razor-thin margin of victory. The United Kingdom is now on its third prime minister in months. The serious threat of political violence persists in a politically polarized United States.

What happens when the democratic world is led by people whose electorates

largely don’t18 trust19 them20—or even the elections that brought them to power? The potential outcomes include repeated leadership changes, continued chaos around elections, and more contestation of the validity of election results. in parliamentary systems especially, frequent elections introduce volatility that the world can ill afford. if the top of a democracy is unsteady enough, eventually it will shake the foundations.

Fisher has been an executive and convener in leadership and social innovation around the world. He was the founding director of GATHER, Seeds of Peace’s social innovation arm, worked on regional economic development in Israel, and coached and consulted for the climate-finance team at the Hewlett Foundation and the social innovation team at Kaiser Permanente.

European companies could soon have to choose between the Chinese and US markets. While questions of economic relations and technological development are mostly understood as commercial activities in Europe, they are increasingly viewed through the lens of national security in the United States. n China, too, the ability to manufacture advanced technologies such as semiconductor chips is seen as vitally important to the country’s development and security.

Xi Jinping’s speech to the 2022 Party Congress made clear that he intends to double down on developing indigenous technological capabilities, which would not only enable further military advances but create more Chinese technology products that are able to compete with US suppliers. Historically, after developing strong domestic production capacity in a particular area, China has gone around the world and undercut other markets and suppliers. The risk this situation poses to US and European competitive advantage is compound: Companies usually fund research and development (R&D) as a fraction of their sales, and if sales drop then R&D funding declines and innovation slows. The United States is attempting to assert its technological leadership and hinder China’s technological advancement in two ways: promoting (through measures such as the 2022 CHiPS and Science Act) and protecting (through measures such as export controls) domestic industry. But both methods carry significant risks of unintended consequences. By reducing revenue for US companies that do business in China, for example, the “protect” strategy is likely to reduce the capital available from the private sector that the US government is counting on to reshore or “friend-shore” manufacturing capacity, putting US industry further behind Chinese industry in R&D investments. Some US partners are already so dependent on China either as a market for their domestic industries or as a supplier of critical technologies that full-blown tech decoupling won’t be possible without risking their economic health. This dependence might lead to worsening transatlantic relations and increasing disputes over how to deal with a rising China, which may even contribute to a splintering of the alliance supporting Ukraine.

18 Joe Davidson, “American trust in government near ‘historic lows,’ Pew finds,” The Washington Post, June 9, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost. com/politics/2022/06/09/american-trust-government-pew-survey/

19 “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2022,” Pew Research Center, June 6, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/06/06/public-trustin-government-1958-2022/

20 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, Edelman, January 18, 2022, https://www.edelman.com/trust/2022-trust-barometer

Lloyd Whitman, Senior Director, GeoTech Center

Lloyd Whitman, Senior Director, GeoTech Center

Whitman had a distinguished federal career in science and technology research and policy. His most recent post was at the National Science Foundation as assistant to the director for science policy and planning, where he worked closely with the White House to promote US leadership in emerging technologies.

We should pay attention to Putin’s efforts to use Russian energy supplies as a weapon to break Western support for Ukraine. But that support has held steady even as temperatures have started dropping and as the Nord Stream pipelines carrying Russian gas to Europe have suffered apparent sabotage. These are among the many signs presaging support that lasts the winter, which could result in Western arms continuing to flow into Ukraine and the Russian military continuing to struggle on the battlefield.

if Ukraine wins the war in 2023—a big if, but not the unthinkable prospect it was a year ago—and eventually joins the European Union and NATO, the upside potential is enormous. And not only for Ukraine: Such developments would represent a huge success for US leadership in Europe and the future of the rules-based international system.

Matthew Kroenig, Senior Director, Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security

Kroenig currently sits on the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States. He served in defense and intelligence roles in the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations. From 2017 to 2021, he was a senior policy adviser to the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capability/Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy.

Net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions could be within sight by 2050 if we play our cards right. The 2022 inflation Reduction Act alone represents the single largest investment in climate and energy in American history, presenting an unprecedented opportunity for the United States and its friends and allies to establish durable and secure supply chains that will accelerate the world’s march to net-zero emissions. Add to this the Bipartisan infrastructure Law and the renewed focus in Western capitals this past year on diversifying away from reliance on Russian and Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) energy supply, and 2023 could be a bellwether year for the clean-energy transition.

To fully capitalize on the momentum, however, Washington needs to get out of its own way. There is a need to build conventional and clean-energy infrastructure, but that can’t happen until Congress passes permitting reform that would make it easier to produce oil and gas resources and move electrons from clean-energy sources in the United States. Such permitting reform has bipartisan support, but the odds of a polarized Congress passing it remain low—jeopardizing the country’s ability in 2023 to scale investment and seize this potential inflection point in the global transition from fossil fuels to clean energy.

Landon Derentz, Senior Director, Global Energy Center

Derentz is the former director of Middle Eastern and African affairs at the US Department of Energy. He served in energy-related roles at the National Security Council and National Economic Council, and under three energy secretaries.

NATO had a strong interest in a more stable Black Sea region even before Russia invaded Ukraine, but in 2023 securing the region will only grow in importance. As the Alliance’s second-largest military power and the country controlling the only way in and out of the Black Sea, Turkey has a pivotal role to play in ensuring the region’s stability and security.

There have been signs in 2022 that Ankara is willing to put this influence to good use, leveraging its connections with both Ukraine and Russia to push for direct peace talks between the two sides. Turkish Bayraktar drones have been instrumental in Ukraine’s defense, while Turkey has also leveraged its longstanding relations with Russia to facilitate, alongside the United Nations, an agreement with Moscow and Kyiv that unlocked the export of Ukrainian grain and lowered the risk of a global food crisis. Turkey is likely to continue to push for a settlement to the war in 2023. Should one start to take shape, Turkey could emerge as a security guarantor and regional counterweight to Russia. Turkish gas discoveries in the Black Sea also have the potential to bolster regional energy security and diversify energy supplies.

Arslan is an economist and energy expert based in Turkey, with long experience liaising between regional governments and the private sector. Arslan worked as a senior economist at the US embassy in Ankara and was the founding coordinator at the Turkish International Cooperation Agency.

if the United States were to reassert its economic leadership in Asia, which it more or less relinquished after the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact fell victim to domestic politics in 2017, it would serve as a response to the economic influence that China has racked up there in the intervening years. it would also represent an important shift from the US government’s primarily security-focused approach to the region.

Look for significant progress in US efforts to bolster economic ties in Asia by the time of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in San Francisco next November. Of particular note would be the finalization of negotiations on the indo-Pacific Economic Framework as well as significant progress in negotiations on the 21st Century Trade initiative between the United States and Taiwan, which is meant to be a move closer toward a free-trade agreement. Collectively those achievements would show that the Biden administration is making good on its rhetoric about US commitment to the indo-Pacific going beyond China to focus on benefits for countries across the region. it would also indicate that the United States is resuming its role of regional economic integrator and is prepared to offer a robust alternative to the China model.

David Shullman, Senior Director, Global China HubShullman oversaw the International Republican Institute’s work building the resilience of democratic institutions around the world against the influence of China, Russia, and other autocracies. For nearly a dozen years he was one of the US government’s top experts on East Asia, most recently as deputy national intelligence officer for East Asia on the National Intelligence Council.

Putin is in deep water as the Russian military flounders in Ukraine. f the transatlantic community maintains its policy of support for Ukraine and pushback against the Kremlin—and especially if such support increases, leading to Kyiv regaining control of most of mainland Ukraine —don’t rule out Putin’s departure from power in 2023. The chances of that occurring, in fact, might be as high as 25 percent. Such a development would most likely flow from increasing economic pain and war casualties producing civil unrest in Russia, all of which prompts insiders to band together to push Putin out of office.

Some fear that any plausible replacement would be worse than Putin. But if past is prologue, the chances of Putin’s removal producing a political and diplomatic opening of some kind is significantly higher than that of an even more brutal and aggressive Kremlin policy emerging. if Putin’s failure in Ukraine leads to more than the already-unusual public discontent on display now in Russia, and to real

political change in the country, that raises the possibility of at least limited liberalization and normalization of bilateral ties with the United States.

John Herbst, Senior Director, Eurasia Center

Herbst’s 31-year career in the US Foreign Service included time as US ambassador to Uzbekistan, other service in and with post-Soviet states, and his appointment as US ambassador to Ukraine from 2003 to 2006. In that role he helped ensure the conduct of a fair Ukrainian presidential election and prevent violence during the Orange Revolution.

Three factors could push Europe to move from debate to action on the question of a more geopolitical European Union. The first is Putin’s aggression in Ukraine. The second is China’s global assertiveness. The third is the potential return of Donald Trump to the US presidency in 2024.

For many European leaders, the past year’s dramatic developments answered some of the unresolved questions about European strategic autonomy. Russia’s war unequivocally underscored the United States’ indispensable role in European security. t also killed any remaining illusions about a European special relationship with Russia and converted even the most dovish proponents of that position in Berlin. Europeans are now much more strategically aligned on the question of the European Union’s relationship with power, even if the EU’s instruments for exercising hard power are still lacking. More hawkish views on China are on the ascendancy in the region as well. The coming year will be about how to put these ideas into practice geopolitically, diplomatically, and especially militarily. What might that look like exactly? if EU military aid continues to flow to Ukraine, that would be an indication that the shift to a more geopolitical EU is happening in practice. in Berlin, it could take the form of operationalizing the government’s ambitious Zeitenwende concept21 for how to engineer a turning point in German foreign and defense policy. Elsewhere, watch for the European Peace Facility (the security-assistance fund from which EU military support for Ukraine is drawn) to be replenished.

Fleck was chief of staff for a member of the European Parliament and then director of the Transatlantic Policy Network. At the Atlantic Council he continues his work liaising with US and EU lawmakers on diplomatic relations, trade policy, and EU foreign and security policy.

The United States demonstrates that “America is back” economically in Asia21 Rachel Rizzo and Jörn Fleck,

“Germany can’t afford to fumble the ‘Zeitenwende’,” Atlantic Council New Atlanticist November 3, 2022, https:// www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/germany-cant-afford-to-fumble-the-zeitenwende/

Authoritarian Russia’s war against democratic Ukraine has had a boomerang effect on the Kremlin by prompting NATO’s expansion to the north to include Finland and Sweden. Now it may have a similar effect by propelling the European Union’s expansion to the south. As i know from experience in my native Romania, many former communist countries view EU membership as a means of escaping their oppressive Soviet past and the Russian sphere of influence with all its pathologies, including corruption, authoritarianism, and arbitrariness—as a way, in other words, of moving to a Western world of democracy, free markets, and rule of law.

Just as the Ukrainian government applied to join the EU within days of Russia’s further invasion of the country, leading the EU to speedily accept Ukraine’s candidacy (and that of Moldova), the conflict may well accelerate the EU membership bids of the Western Balkans countries in the coming year. Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia will likely feel increased urgency to obtain the greater prosperity and security that they believe EU membership would provide, and EU leaders could be more inclined to embrace them—as Germany’s chancellor, for example, has recently signaled.22

Negrea was the State Department’s special representative for commercial and business affairs from 2019-2021, and he held the economic portfolio in the secretary of state’s Policy Planning office from 2018-2019. He began his career as an official in the Ministry of Finance in Communist Romania, then defected to the United States and went on to a three-decade career on Wall Street.

Beginning with the November 26 announcement that the United States will issue a new license for Chevron to pump oil in Venezuela, the political space is opening for the United States to further lift the oil sanctions it imposed in 2019 in response to the increasing authoritarianism of Venezuela’s leader Nicolás Maduro. The interim government of Juan Guaidó, which the United States and more than fifty other countries recognized as the country’s legitimate leadership, will cease to exist in January when Guaidó’s term ends.