ArtSeen

Saul Steinberg: Imagined Interiors

On View

Pace GalleryNew York

The intimate drawings in this virtual show, astutely curated by Michaëla Mohrmann, associate curatorial director at Pace, take viewers on a charming, witty, ironic, and droll perambulation through the landscape of Saul Steinberg’s mind. Here you’ll take unexpected detours; meet solemn, judgmental cats, bespectacled dogs, and angry birds; and forage through a ridiculously jam-packed Victorian interior replete with bourgeois artifacts, including African sculptures, a tiger rug, and a wall of musical instruments.

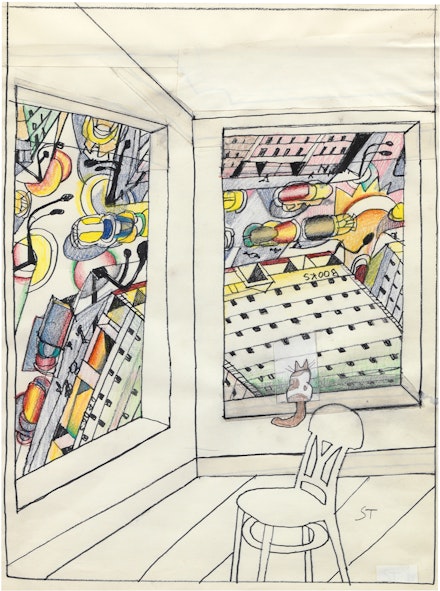

Visitors can also get trapped in impossible perspectives—sitting in a barren space between two windows in a skyscraper with a vertiginous perspective onto the streets in the Pop-colored drawing Looking Down (1988), where the windows below resemble typewriter keys; or gazing at an upside-down woman in a gelatin-silver print from 1950 in which the figure looks etched in glass with her hands on the wood floor beyond the wall.

This show reveals how Steinberg drew mental lines connecting the many realities of his experience. He pictures his Romanian youth in a poor village, portraying a room with a drawing of his parents on the wall, a threateningly vibrating tiger woven into a rug beneath a violin-practicing, foot-tapping child with a big man’s nose, and an open window onto the village beyond.

Much later, he depicted the great village of his adulthood—Manhattan. Here is his iconic The New Yorker magazine cover View of the World from Ninth Avenue (1976) also aptly known as A Parochial New Yorker's View of the World, with a perspective reaching across the Hudson River, first to New Jersey and then some states in the middle, and finally on to China, Japan, and Russia. It’s the world as if packed into his study as a narcissistic geographical tool. In some ways, it’s a de Chirico-esque perspective, compressing distance, associations, and content.

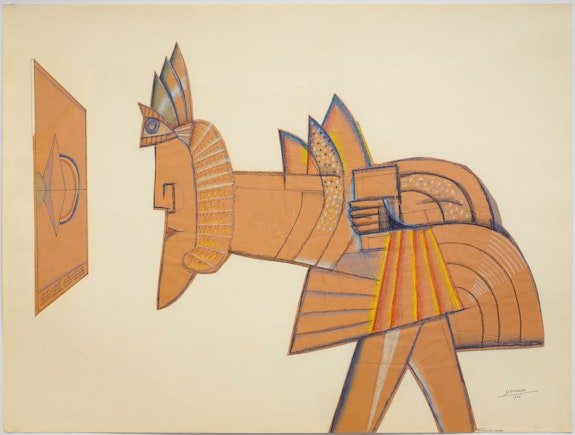

Steinberg was a world shrinker—sophisticated, philosophical, literate, and cosmopolitan. His shorthand vision of geography maps his mind and sense of time and place; his life was like a Rube Goldberg adventure, highlighted by absurdity—theatrical and metaphysical. This mapping includes much art about art and the artist creating his art as a way to create a world. His crayon, graphite, colored pencil, and pen on ink on brown craft paper drawing Sphinx II (1966) shows a modernist cutout figure gazing at a flattened Paul Klee–like drawing of itself.

Steinberg’s modernism, embracing the many contemporaneous and stylish movements of the 20th century, extends to a frenzied futuristic display in Speeding Still Life (1979), set out precariously on a simple work table; the ink, rubber stamp, and pencil on paper drawing hints at a confused reflection on Italian Futurism. The picture’s components balance precariously on the table.

Swiss Still Life (1988), by contrast, is more enigmatic—or simply “absurd,” with a sculpture of a cute stylized woman’s figure vaguely draped. "I play with the absurdity of reality,” he said. “There is something absurd about what we consider to be real—even what we consider to be absurd." And even more to the point is the drawing Bedroom Sphinx (1987) showing a slightly disheveled sphinx presiding from a very Art Deco bed being gazed at by a monkey bellhop.

Steinberg willingly poked fun of himself through the subjects of his own creation. His Untitled (Drawing Table) (1966) takes the viewer through his cubistic head as he draws himself into his composition featuring a tough, statuesque cat on the table at his right and, in an abrupt shift, a window onto a lounge area with puffy seating perhaps trying to seduce him away from his work, and probably succeeding, as we see a man with a scratched-out face reclining as if drawing a blank.

Most revelatory of the artist in his interior is a small (roughly 14 by 23 inches) untitled drawing from 1981, in which a bird-artist-man sits intently at his desk in a large living room, with big windows and a grand array of his animal characters expressionlessly confronting him. A large doggish wife figure presides: A Steinbergian version of Gustave Courbet’s The Artist’s Studio (1854–1855).