WILLY RONIS LIFE, EN PASSANT

DIALOGUE

CAROLE NAGGAR

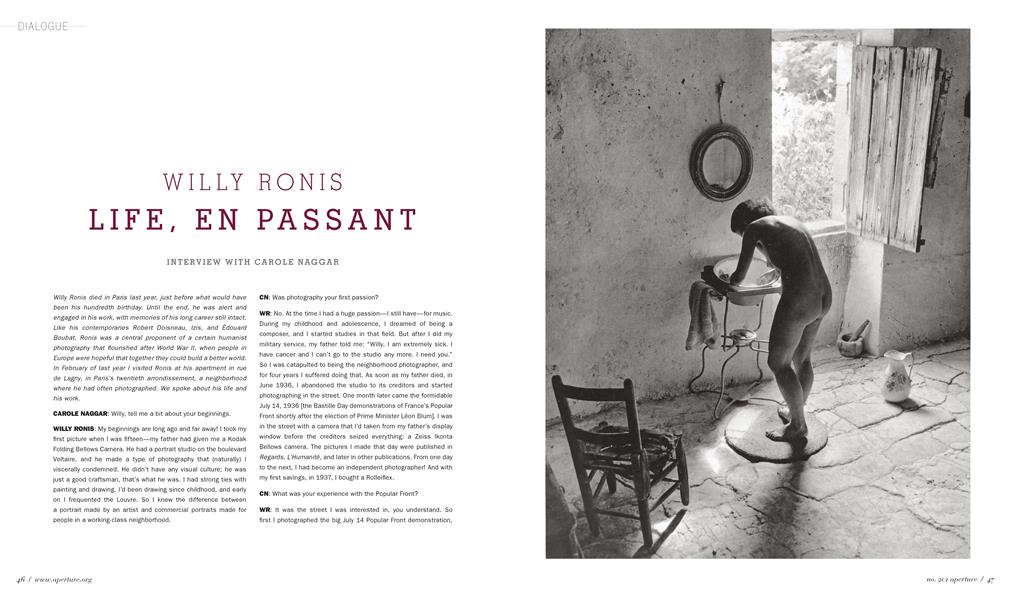

Willy Ronis died in Paris last year, just before what would have been his hundredth birthday. Until the end, he was alert and engaged in his work, with memories of his long career still intact. Like his contemporaries Robert Doisneau, Izis, and Édouard Boubat, Ronis was a central proponent of a certain humanist photography that flourished after World War II, when people in Europe were hopeful that together they could build a better world. In February of last year I visited Ronis at his apartment in rue de Lagny, in Paris’s twentieth arrondissement, a neighborhood where he had often photographed. We spoke about his life and his work.

CAROLE NAGGAR: Willy, tell me a bit about your beginnings.

WILLY RONIS: My beginnings are long ago and far away! I took my first picture when I was fifteen—my father had given me a Kodak Folding Bellows Camera. He had a portrait studio on the boulevard Voltaire, and he made a type of photography that (naturally) I viscerally condemned. He didn’t have any visual culture; he was just a good craftsman, that’s what he was. I had strong ties with painting and drawing. I’d been drawing since childhood, and early on I frequented the Louvre. So I knew the difference between a portrait made by an artist and commercial portraits made for people in a working-class neighborhood.

CN: Was photography your first passion?

WR: No. At the time I had a huge passion—I still have—for music. During my childhood and adolescence, I dreamed of being a composer, and I started studies in that field. But after I did my military service, my father told me: “Willy, I am extremely sick. I have cancer and I can’t go to the studio any more. I need you.” So I was catapulted to being the neighborhood photographer, and for four years I suffered doing that. As soon as my father died, in June 1936, I abandoned the studio to its creditors and started photographing in the street. One month later came the formidable July 14, 1936 [the Bastille Day demonstrations of France’s Popular Front shortly after the election of Prime Minister Léon Blum]. I was in the street with a camera that I’d taken from my father’s display window before the creditors seized everything: a Zeiss Ikonta Bellows camera. The pictures I made that day were published in Regards, L’Humanité, and later in other publications. From one day to the next, I had become an independent photographer! And with my first savings, in 1937, I bought a Rolleiflex.

CN: What was your experience with the Popular Front?

WR: It was the street I was interested in, you understand. So first I photographed the big July 14 Popular Front demonstration, then other rallies. Besides the general-interest pieces, Regards assigned me political and social material: strikes, demonstrations. . . . That’s what I did until the war came.

CN: Did you meet other photographers?

WR: I met Chim [David Seymour] in 1935. Friends of mine had told him that I worked in my father’s studio and that we had a glazing machine. Chim developed his films in a little chambre de bonne, so he didn’t have one. Chim was a very smart guy, very well educated, but rather dark, melancholy, and introverted. Through Chim I met Robert Capa, with whom I had a wonderful friendship. One would have thought that with Capa’s enormously extroverted side we might not have been compatible—I am much more reserved—but in fact we got along famously, and before the war we saw each other often.

When World War II came I was enlisted, like many of my friends, and sent to a military camp—an air-force camp. Then I was given a job in a gunpowder factory in Bergerac; later I was demobilized and came back to Paris. As you can imagine, Paris in October 1940 wasn’t much fun. I couldn’t find work as an independent photographer. Finally I got a job making window displays for the Printemps department store. I shot photographs, hand-colorized them in my bathtub, and made photomontages. But soon I thought: “The atmosphere here is too dangerous.” I am of Jewish descent—my mother is from Lithuania and my father from Odessa. I couldn’t stay in Paris.

So in June 1941 I went south. I took some small jobs through the poet Jacques Prévert’s circle of friends, and in the movies with set-designer Alexandre Trauner. I met them in the village of Tourrettes-sur-Loup, where they were both staying—and I had a wonderful friendship with them.

CN: What kind of photographic work were you doing?

WR: I went back and forth twice between the German frontier and Paris. There was a tremendous amount of surveillance. We did not want Gestapo people to infiltrate France, so the trips between the German frontier and Paris took several days. Some of the photographs I took during those trips are still occasionally published nowadays.

I also made contact with the editors of several weeklies and monthlies, such as Point de vue and L’Illustration, and did a lot of stories for them. After the war, back in Paris, there was a great blossoming of illustrated magazines that needed photographers who knew how to work. ... I did everything. I formed a close relationship with France’s minister of tourism, who needed photographs for their publications; and for the SNCF [Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer: the French railway board], which needed a lot of landscape photographs. After the Liberation, I was asked to shoot a big story on the return of the deportees and prisoners of war.

CN: Did you still find time to work for yourself?

WR: Oh yes, I always did. I never went out without my camera, even to buy bread.

CN: What was your relationship with Life magazine?

WR: Something happened that was quite typical of my personality. Life asked me if they could reuse some political photographs that I had done. I said: “I agree, but I want control over my captions.” To ask for that type of control was considered incredibly presumptuous. Life said yes—but after that they never assigned me anything.

CN: How did you start work on your book Belleville-Ménilmontant [Arthaud, 1954]?

WR: My wife, Marie-Anne Lansiaux, was a painter. She knew a very nice artist named Daniel Pipard, who invited us up to his house on the rue de Ménilmontant. I didn’t know the Belleville-Ménilmontant area of Paris at all, and when I went I was deeply moved. It was a village in the hills, with marvelous light. . . . The tourist buses never went there; there were no monuments. People kept to themselves. There is still something of it left today; the hills haven’t been razed. And it’s still special, a habitat with stairways and small houses. I fell in love with that neighborhood. I couldn’t get there every week, but between assignments I would jump on my motorcycle and go. I started in November 1947 and by 1950 the project was finished. Belleville-Ménilmontant was printed in photogravure on beautiful paper, with a layout by Roger Excoffon. The book was well received but it wasn’t a great commercial success.

CN: When did you meet Robert Doisneau?

WR: I met Robert in 1946-47, when I joined the Rapho agency, where he was already a member. He was a wonderful man. I liked him a lot but we didn’t see each other much—photographers don’t, you know; you are never free at the same time, and then you also have a family—war photographers are very often bachelors. Doisneau had two daughters, and I had Vincent, my wife’s son, whom I met when he was two years old, so he became my son.

CN: How long did you stay with the agency?

WR: We got on for a long time, but eventually there was a crisis. I suppose I am too principled: there were certain publications with which I didn’t want to work, and I could see that it was causing problems at the agency. It wasn’t practical if they had to ask themselves every time: “What will Willy think if we give a picture to such and such a newspaper?” It was during the Cold War, and that affected me a lot—at the time I was in the Communist party. So I realized that the situation at Rapho had become tense, and I told them: “Look, kids, we’re good friends, we’ve never argued, and I won’t be angry at all when I leave you, though I’ll be a little sad. But I am causing a problem for you, and I don’t want it to go on. So I am going to fly with my own wings, and we’ll see what happens.”

CN: How did it go?

WR: It was very hard. One day I was there, and the next I’d disappeared. I had to do the rounds of all the editors with my book under my arm like a beginner. All that happened in 1955. And then, starting in the early 1960s—with the influence of the American and British press—priority began to be given to the “scoop.” Me, I have never been a scoop photographer. My thing was rather the non-event, the atmosphere, people in their milieus.

CN: So what did you do after the world of the magazines changed?

WR: In the 1960s I realized that the photography I liked and with which I made my living was not in fashion anymore and that I had to find something else. I got work thanks to Janine Niépce, a photographer who had done many jobs for France’s ministry of foreign affairs. That work allowed Marie-Anne and me to leave for Gordes, in the South of France, where we had a vacation home—a ruin, really, that I rebuilt according to my needs and those of my wife. I have adored architecture since I was young, and I drew up the plans for our house. We stayed eleven years in the South. I did color stories on Provence for Paris publishers and I taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Avignon and at the Université de Provence in Aix. I had thought that we would live in the South until the end of our days, but Marie-Anne’s health started deteriorating; she had Alzheimer’s. We had to come back to Paris.

Also, my work was having a certain success, and long-distance professional relationships were too complicated. After we came back in 1983, I had plenty of work. I had been a guest of honor at the Rencontres d’Arles in 1979, and received the Grand Prix de la Photographie—that brought new attention to my work.

CN: You started out thinking that you would be a musician. Do you think there’s music in your photographs?

WR: I recently published a book called Derrière l’objectif (Behind the lens; Hoëbeke, 2010), where I comment on my photographs.

It’s not really a treatise—but I talk about my way of thinking up to the moment when the photograph gets made, and why it is made in this particular manner. There is no doubt for me that the music is there.

CN: Which cameras have you used?

WR: First the Rollei, then in 1955 I started with the small format and I never went back to the 6-by-6 format. It was not that different, because already with the Rolleiflex, I was using a sports lens that I brought up to my eye. I never used a Leica because I found it scandalously expensive.

In the early 1950s I met with the director of Optique et Précision de Levallois, the makers of the Foca camera. There was a Foca Universel that was exactly like the Leica except it was made in France, and it had a 50-millimeter lens that was even better than

the Leica’s. In exchange for articles that I wrote and illustrated for the company’s magazine, I received a camera. The only downside of the Foca is the noise. You cannot deny that the Leica’s shutter release is silent. I regretted that—but it didn’t really bother me since I was photographing in the street.

CN: What about Izis? There is a kind of spiritual kinship between you, I think.

WR: We are both of the same origin: Jews from Lithuania. I got to know him just after the Liberation. Izis spoke French very badly, and it so happened that I was next to him one day and I recognized his accent—so I approached him and said: “My mother came from Lithuania too, so if there are things you don’t understand or if you need help with anything, call me, we’ll get together.” And we became very close friends, like brothers. After the war professional supplies were rationed. He and I founded a small association of photoillustrators so that we could get materials: photographic paper and so on. Later on, we couldn’t see each other much because we were both working, and he also had serious health problems—both physical and mental. But in a way, that made us even closer.

Once I published a story in a magazine with the title “An Old House in an Old Village.” It was my house, my ruin where I shot the Nu provençal (Provençal nude; 1949). I didn’t name the place but I told a whole story with pictures. The evening the story comes out, Izis calls me, very excited, and says: “Willy, what’s that village—I want a house in that village!” I knew of a house that was available, and he bought it. So during every vacation, I spent at least half an hour with him every day on my way home from the village after running errands. So we saw each other a lot. It was a very, very deep friendship.

CN: What role has photography played in your life?

WR: With photography I felt at ease almost right away. It brought me deep emotions, it allowed me to meet people, and also to travel a bit. I was very happy in photography. The 1960s were hard, but it ended up well.

Ronis shows me the last picture he took of his wife, Marie-Anne, before she died. It was in the fall and the trees were starting to lose their leaves. He had photographed her from afar, sitting on a bench at the end of their favorite walk. At the end of a tunnel of light, her small silhouette blends in with the landscape and the hundreds of leaves that surround her like a cloud of snow. It is his good-bye to her. The photograph is discreet and tender, an atmosphere one finds in much of Willy Ronis’s work. ©

Translated from the French and edited by the author.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Witness

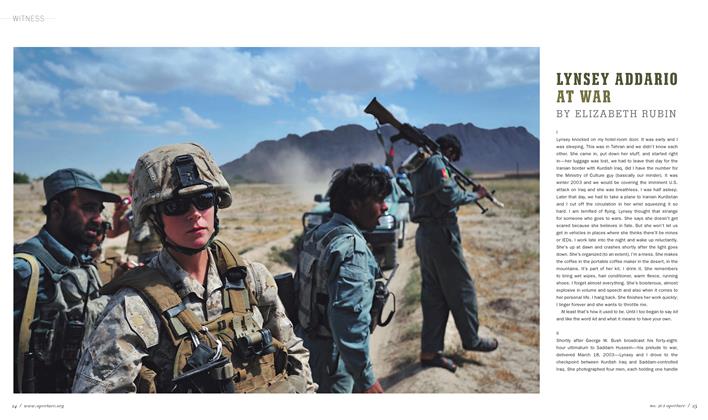

WitnessLynsey Addario At War

Winter 2010 By Elizabeth Rubin -

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsState Of Exception

Winter 2010 By Ben Sloat -

Portfolio

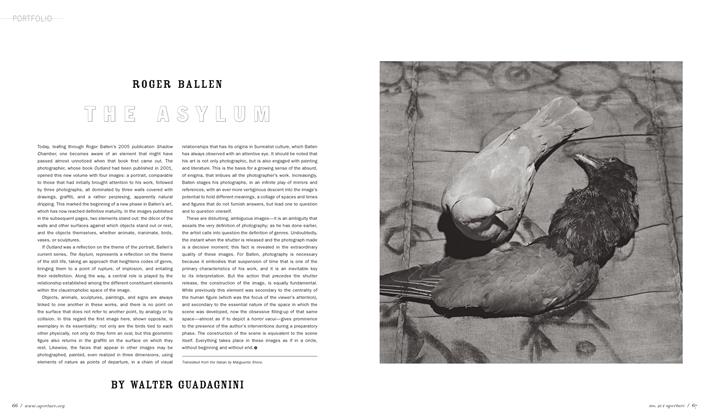

PortfolioRoger Ballen The Asylum

Winter 2010 By Walter Guadagnini -

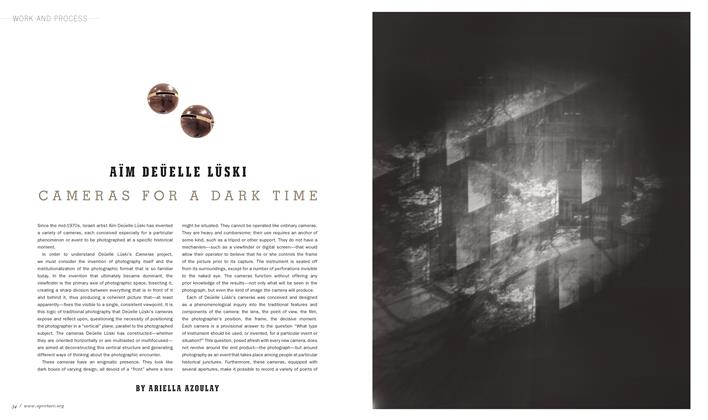

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAïm Deüelle Lüski Cameras For A Dark Time

Winter 2010 By Ariella Azoulay -

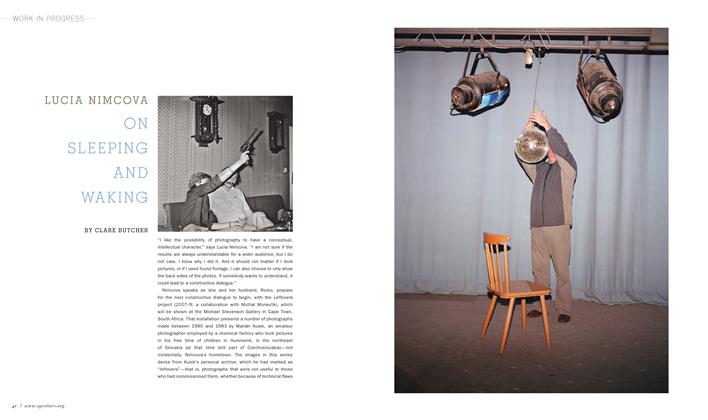

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressLucia Nimcova On Sleeping And Waking

Winter 2010 By Clare Butcher -

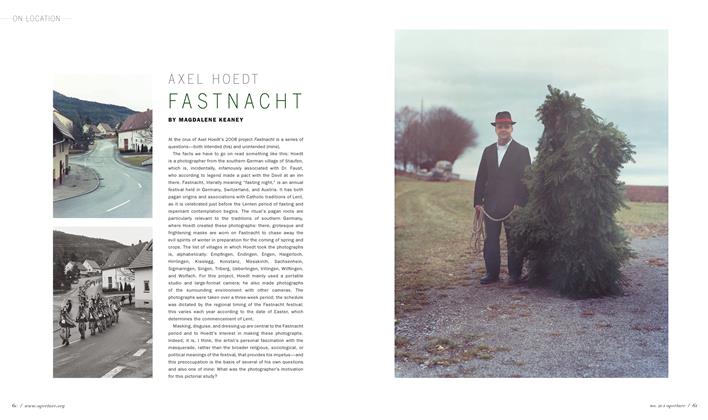

On Location

On LocationAxel Hoedt Fastnacht

Winter 2010 By Magdalene Keaney

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Carole Naggar

-

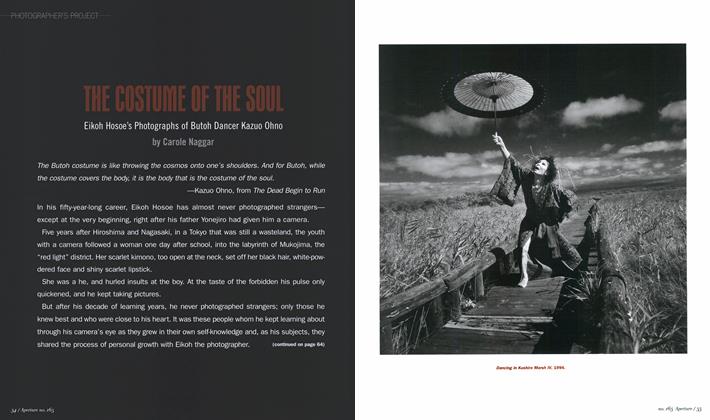

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectThe Costume Of The Soul

Winter 2001 By Carole Naggar -

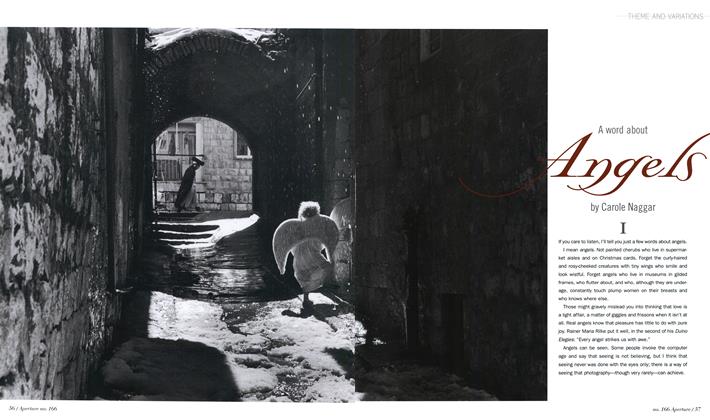

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsA Word About Angels

Spring 2002 By Carole Naggar -

Reviews

ReviewsThomas Struth: 1977-2002

Fall 2003 By Carole Naggar -

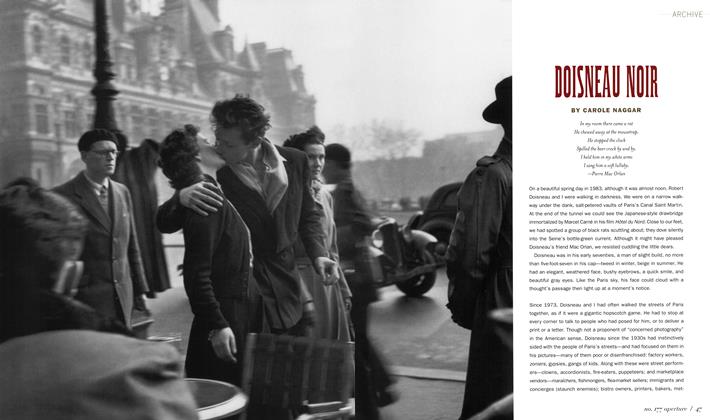

Archive

ArchiveDoisneau Noir

Winter 2004 By Carole Naggar -

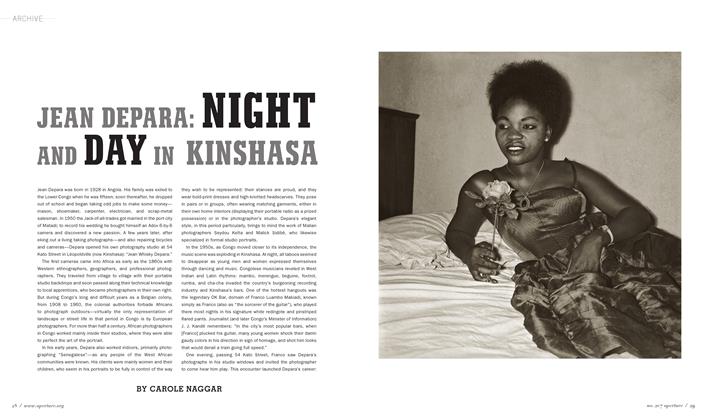

Archive

ArchiveJean Depara: Night And Day In Kinshasa

Summer 2012 By Carole Naggar -

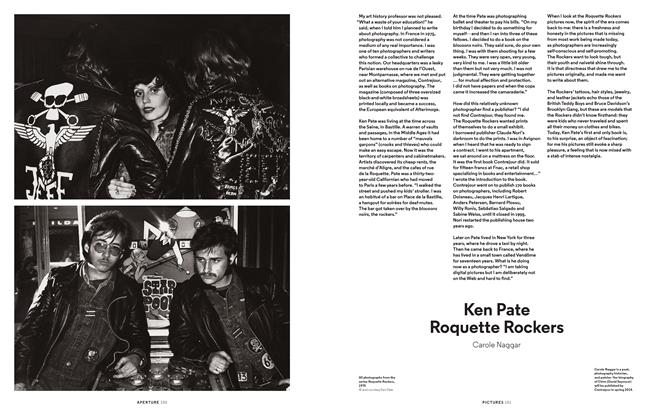

Pictures

PicturesKen Pate Roquette Rockers

Winter 2013 By Carole Naggar

Dialogue

-

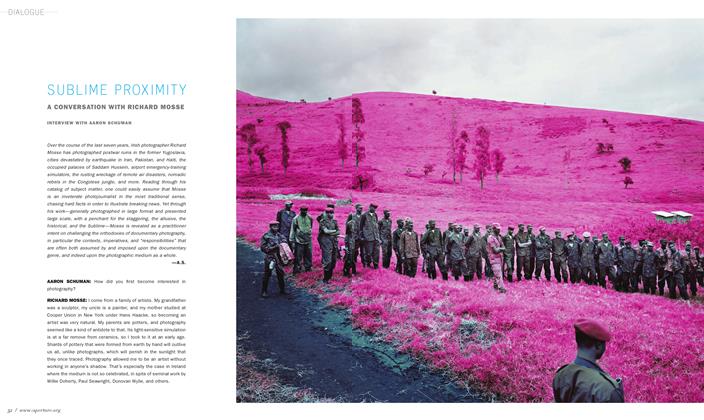

Dialogue

DialogueSublime Proximity

Summer 2011 By Aaron Schuman -

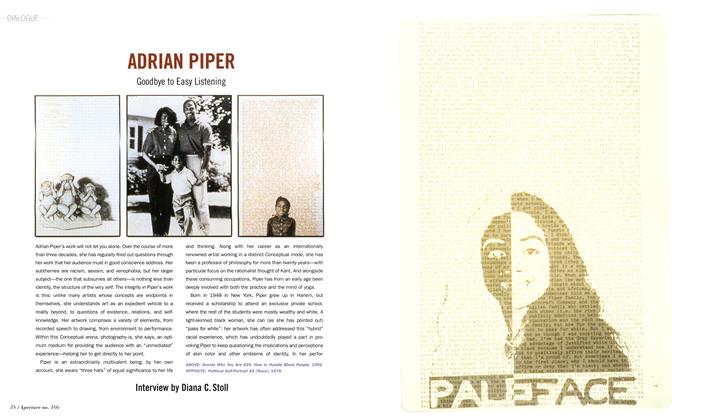

Dialogue

DialogueAdrian Piper

Spring 2002 By Diana C. Stoll -

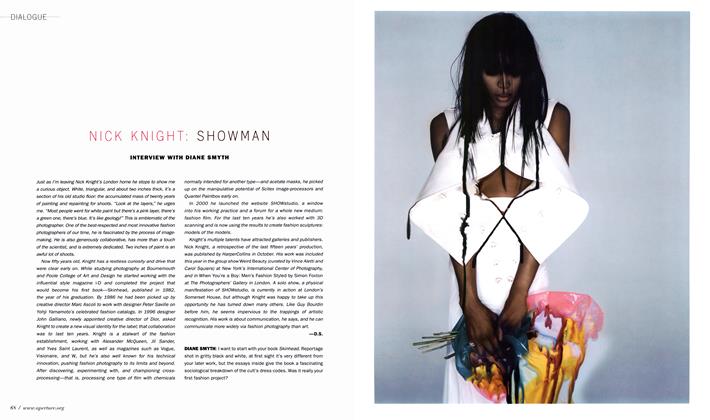

Dialogue

DialogueNick Knight: Showman

Winter 2009 By Diane Smyth -

Dialogue

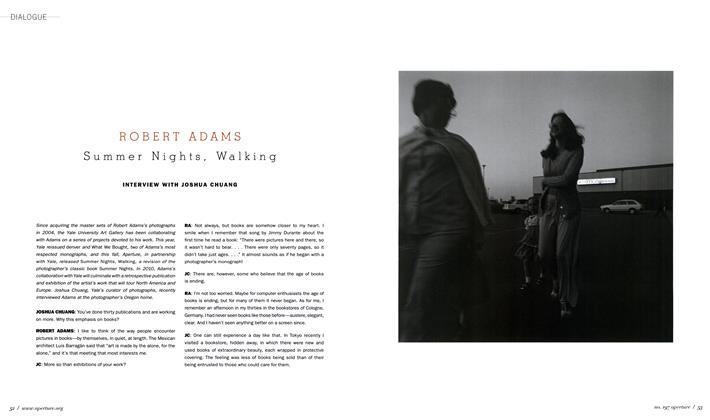

DialogueRobert Adams Summer Nights, Walking

Winter 2009 By Joshua Chuang -

Dialogue

DialogueInvasion 68: Prague

Fall 2008 By Melissa Harris -

Dialogue

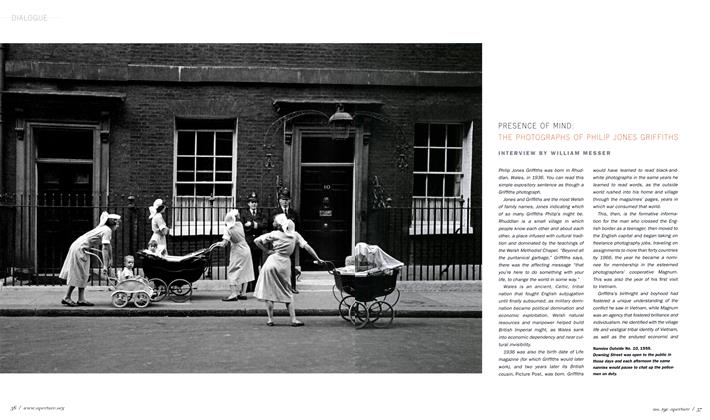

DialoguePresence Of Mind: The Photographs Of Philip Jones Griffiths

Spring 2008 By William Messer