Page under construction!

This page is a work in progress for me that I have been slowly creating over the last few years. It is a labor of love that I try to work on when I can between projects and paintings. I am excited to see it grow, and hope that is of interest to you as well!

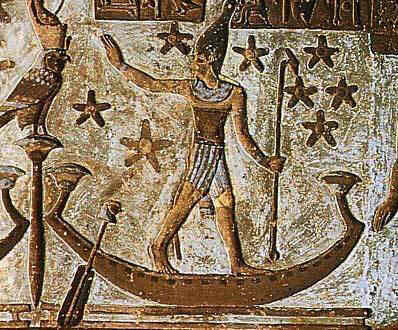

A’ah

A’ah was an early Egyptian moon god who created and controlled the calendar of the ancient lunar year - 12 months of 30 days each. The heavens were meticulously and comprehensively charted by the Egyptians, including the stars, planets, sun, and moon - but it was the phases of the moon that they used specifically to measure time. Since the priests used the lunar calendar to help inform the planning of agriculture that constituted a large amount of Egypt’s wealth, this led to him being considered a fertility god. Even though they were unable to anticipate the Nile's flooding with any degree of accuracy using the lunar calendar, the flooding was so significant that they arranged the months according to it. The period of the flood was Akhet (June–September). Peret (October-January) was the time of planting, and Shemu (February-May) was the time of harvest. This system did leave an extra five days in the year though.

A’ah is said to have won a wager with Thoth over a game of dice that ended up in him winning enough lunar light to create 5 extra days. He is credited with adding 5 extra days to the year thus allowing Nuit, who had been cursed by Ra against having children any day of the year, to give birth to her children with Geb: Isis, Osiris, Nephthys and Set.

A’ah evolved into Iah (sometimes spelled Yah) and eventually, Khonsu and Osiris - but his original name, A’ah was the Egyptian word for moon. The Egyptians eventually understood that Sirius, also known as the 'dog star', rose with the sun every day of the year and could be used to predict the Nile's flooding accurately. The lunar calendar was then replaced with a solar calendar. This could explain why A’ah is often shown with both a crescent moon and a solar disk on his crown.

A’ah was represented as a young student, and pupil of Thoth, and as such was regarded as a patron of students. His symbols were the crescent and full moon, as well as the ibis and falcon.

The Aai

3 guardian deities in the ninth division of Duat; they are Ab-ta, Anhefta, and Ermen-ta

Aani

Aani was a protector, dog-headed ape, a creature sacred to the god Thoth.

Abaset

Abaset is depicted as a woman in a red dress wearing a vulture headdress with uraeus cobra at the forehead and a distinctive hedgehog element on top.

Abtu

Abtu (Abdu or Abdju) is the name of a sacred fish who swam with Anet (Ant or Int or Inet) before the barge of Ra, the Atet. The pilot fish, Abtu and his companion and sister Anet were worshipped for protecting Ra - swimming on either side of the front of the prow of the sun barge as Ra sailed through the dark waters of Nun to sunrise, protecting it from any dangers of the underworld. Abtu was said to be a golden fish who would loudly proclaim the arrival and threat of Apep, while Anet was said to be a red fish who would physically defend the boat with the great gods.

Abtu, the golden fish was said to have, ‘a screaming voice… in the house of Neith’. The stela further reads - “a loud voice is in the Mouth of the Cat. Gods and Goddesses say: ‘Look, look at the Abtu fish and at its birth. Turn your steps away from me, wicked one. Look, Ra is furious and raging because of it. He has commanded your execution to be carried out. Turn back, wicked one!” (The wicked one being Apep)

As for the fish itself, we don’t know for certain what species it was meant to be, but at times is considered to be tilapia - which is also said to be a manifestation of Ra. Abtu was an edible species of fish as it is an ingredient in medical recipes and magical spells to protect spaces.

The goddess Isis was said to have transformed into the Abtu, the Great Fish of the Abyss, and within the city of Oxyrhynchus, was said to have been the fish that swallowed Osiris’s penis when he was dismembered by Set. The fish cult spread to many parts of Egypt.

Abtu was also the Egyptian word for the west which was the place where the sun’s passage of day across the sky ended - so for ancient Egypt where the sun dies each day and passes into the dark underworld.

A hymn said to have been sung by the Ogdoad to Amun-Ra makes reference to both fishes:

“…You navigate over your two heavens without an opponent,

your flaming breath has burned the evil one.

The red fishes are controlled by your boat,

the abdu fish has announced to you the wenti-snake,

the Ombite (Horus) has fixed his spear in his body. …“

See also - Anet

Abu

Abu was an early Egyptian God of Light that was likely worshiped in the city of Elephantine.

Ahti

A malevolent hippopotamus goddess

Aken was a ferryman in the afterlife and custodian of the boat that ferried souls across Lily Lake to the Field of Reeds. Comically, he had to be woken by Mahaf (or Hraf-Hef), a surly ferryman, to do his job.

aKEN

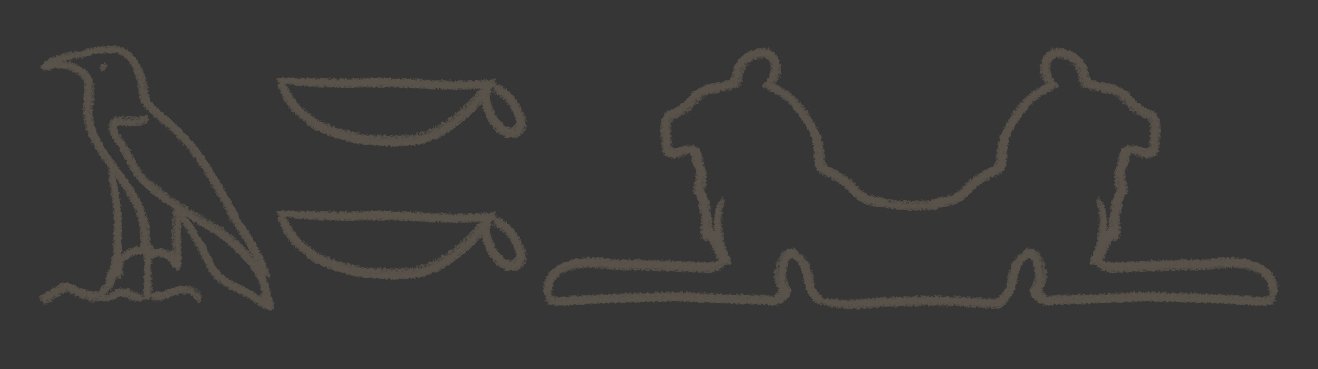

Akeru (Aker/Akheru) was the horizon - deified; an earth god who was guardian of the Eastern and Western horizons and gates to the afterlife. He was a protective deity that guarded the gates of day and night. In later theology, Akeru’s two halves are called Sef (Yesterday) & Tuau/Dua (Today). Conjoined, they symbolize not just the guardians of two different times, but also the continuity of time, merging yesterday and tomorrow in the depths of the netherworld,

Originally, Aker was the oldest lion god and earth god, older even than Gebb. Aker guarded the gate of dawn through which the sun god passed each morning. He was originally depicted as the torso of a recumbent lion with a widely opened mouth.

As Egyptian mythology evolved to describe Ra’s journey through the night as through a dark tunnel, Aker became the pluralized, Akeru - two lions, guardians at each end of the tunnel through the Duat (underworld) through which Ra’s sun barge perilously traveled each night. In this dual form, he was instead depicted as two lions, seated back to back, supporting between them, the horizon and on it, the disk of the sun. And even, as two conjoined lion torsos, or sphinxes looking in opposite directions.

In some texts, Akeru also appears to embody the dark passageway itself - the earth from dusk to dawn, the Duat itself, through which the sun barge and Ra traveled. In the Book of the Earth, Akeru was said even to imprison within himself the coils of the great demon Apep when it was cut to pieces.

In the 5th hour of the sun’s nightly journey through the underworld, Akeru was depicted on either side of the cavern of Sokar. In this cavern, it was said that the ‘secret flesh’ of the sun god’s sacred corpse was guarded by Sokar within the protective body of Akeru. This lifeless, subterranean form of the sun god (Osiris-Soker) was the form in which the morning renewal would begin, and the sun god could rise anew for the new day. As the double-headed sphinx on either side of Sokar’s cavern, Akeru represented the netherworld itself, tasked with guarding the ‘secret flesh’, the sacred corpse of the sun.

As such, Akeru was a symbol of regeneration and potency - as his maw devours in the west, so too does it open and release new life in the east. Through him, all vitality and life force regenerates, both human and god. Akeru more than any other god, guards the mystery of regeneration, for within him lies not just the secret flesh of the sun god, but the corpse of every deceased human and their passage to an afterlife as the blessed living. In the most profound darkness of the earth, Aker guards the mystery of life’s potency - the Ka, and its renewal to conscious life.

In Egyptian texts, it was said that Akeru would not seize upon the Pharaohs as they passed to the afterlife, suggesting that Akeru was, in fact, a threat to other mortals. Naturally, priests devised spells that were said to protect other mortals from Akeru. Despite this, Akeru was seen as a benevolent god and it was said that he could absorb the venom from snake bites and scorpion stings, even protecting the passage of the pharaoh to the underworld by restraining the various serpent demons which threatened him.

Sphinxes - Because the gates of morning and evening itself were guarded by the lion god Akeru, Egyptians placed protective statues of lions at the entrances of palaces, temples, and tombs to guard against evil. These statues served as terrifying guardians, animated against the enemies of Egypt and the divine order. These statues were often given human heads - which are recognizable to us by the name given to them by the Greeks - Sphinxes. These statues were, like Akeru, meant to guard the entrances against evil, either of flesh or spirit, that would harm those inside. Unlike the Greek sphinx, these were not winged or exclusively female; nor did they represent enigmatic wisdom - but rather served as guards to the enigmatic space beyond. These Sphinx guardians most often wore the face of a reigning King or Queen, embodying the power and duty of Egypt’s ruler and defender. The sphinxes could also have the heads of rams, hawks, or even the Seth monster. There were many sphinxes (including Tutu - the sun of Neith), but Akeru seems to have been singular in his role as the two-headed guardian of the dual horizon.

Lions - It is thought that Akeru was represented by a now-extinct (except for a few Zoo specimens) lion - the massive Barbary lion. But some pictures of Akeru show him as two lions, covered with spots, which while not common has been documented as a natural occurrence in some lions. Usually, any markings fade as the lion becomes an adult, but rarely they persist. There are also rare instances of crossbreeding between lions and leopards which does result in offspring that appear to be lions with spots. The lion was sacred to the Egyptians though, and there are even carvings showing that some pharaohs (Ramses 2 and Ramses 3) had pet lions that accompanied them to battle and attacked the enemy - but their value seemed to exceed just their effectiveness in combat. They were valued more as symbols of the sun-god and his protective power.

Akhty

Akhty was believed to reside at the evening horizon, guiding the setting sun and carrying the souls of the deceased safely into the night. He was associated with the bald ibis (Akh bird) which was believed by the Egyptians to represent the human spirit (known as Akh). They compared the shimmering iridescence of the ibis’s feathers to the shimmering stars in the night sky. Similarity, the Persian bedouins worshiped the northern bald ibis as a bearer of the deceased’s soul.

Amathaunta

An ocean goddess

Am-heh

Am-heh was a dangerous god from the underworld whose name can be translated as ‘devourer of millions’, or eater of eternity. He lived in a lake of fire and was represented as a man with the head of a hunting dog. It was said he could only be repelled by the god Atum himself.

Amenhotep

Amenhotep (son of Hapu), along with Hardedef and Imhotep, was one of the few humans defied by the Egyptians. Amenhotep was the royal architect of Amunhotep III and was considered so wise that after his death he was deified. After his death, he acquired a cult as a healer and intermediary to the god Amun. He was worshiped alongside his fellow deified architect and healer, Imhotep. In a hymn, it is said of Amenhotep and Imhotep that they have a single ‘body’ and a single ‘ba’ (soul) - implying Amenhotep was a reincarnation of his deified colleague who lived a thousand years prior.

Amenhotep I

The second king of the eighteenth dynasty, deified.

Ammit

Ammit (Ammut) was a malevolent, demon goddess known as the ‘Devourer of Souls’. She was said to have a crocodile head, torso of a leopard, and hindquarters of a hippo - a combination of the most ferocious, terrifying animals to the Egyptians. She was also represented at times by an owl. In the hieroglyphs of her name, the first owl is phonetic for the ‘m’ sound and the second owl symbolizes death and the soul - showing her as the killer of the soul. She was also known as ‘Dweller in Amenty’ and ‘Devourer of Amenty’ - the place where the sun sets - the west. All of the Egyptian tombs were on the west side of the Nile. This sunset in the west was sometimes shown as a lake of fire that she lay beside.

Ammit was the supernatural demoness who attended the judgement of the soul, as the mortals actions in their earthly life were judged by Osiris, and 42 other deity judges, including Anubis. She waited in the Judgement Hall of the Two Truths while the heart was weighed. The physical heart was called the ‘ib’ and was the source of their good or evil. The physical heart was called the ‘haty’. When the heart was weighed against Ma’at’s feather of truth, she sat beneath the scales in the Hall of Truth in the afterlife. If the heart was found to be heavier than the feather, she devoured it, resulting in a true death of the soul rather than letting the soul pass to the next life. As such, she was the executioner of the afterlife. Once Ammit swallowed the 'Ib', the remaining parts of the soul were believed to become restless forever - this was called "to die a second time". The ancient Egyptians feared the "second-death" even more than the first death.

The soul was extremely important to the Egyptians and they had two variations - the Ka and the Ba. The Ka was the life force, the spiritual essence of the soul. The Ba was a physical essence of the soul that roamed as a bird, usually a hawk, with a human head. The Ba was used to symbolize the soul of the dead. When the two, Ka and Ba, were united they became the Akhu, the divine spark of the soul. Then the dead could enter the world of immortality. However, if they were deemed to have led a sinful life, their Ba would be given to Ammit and destroyed, denying them ever-lasting life.

Ammit was never worshipped and mortals were said to only ever encounter her once, upon their death.

The Book of the Dead was a guide to help ensure that the dead knew how to address the gods properly and convince them of their goodliness in life, as wrong answers to their questions or failure to answer properly would be sign of guilt. Only after passing this judgement without guilt would they be able to enter the ‘House of Reeds’, the Egyptian’s idea of heaven.

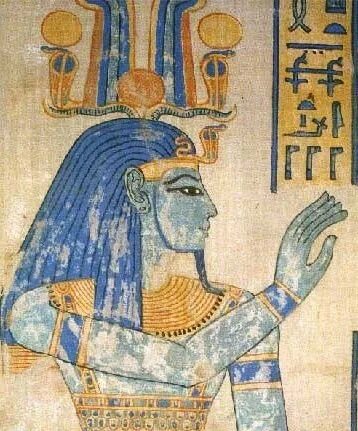

Amentet

Amentet was a goddess who lived in a tree near the gates of the underworld and she welcomed the dead with food and drink to the afterlife. She was a consort of the Divine Ferryman, daughter of Hathor and Horus, and was known as, ‘She of the West’.

Amn

A goddess who welcomed souls of the dead in the Underworld

Amu-Aa

*entry under construction

From Wikipedia - Amu-Aa (eater of the ass) or (eater of the phallus), is one of the gods that goes with Osiris during the second hour of the night. Amu-Aa would eat the bread made for the boat and use the perfume.

From Reddit - This is quite probably something Budge got wrong, and unfortunately whoever wrote that Wikipedia article is not aware that there has been a lot written on Egyptian religion since the beginning of the 20th century.

Although am can indeed mean "to devour," it also means "to know." Likewise, "donkey" is one of the translations of aA, but it also means "gate, door."

While "the one who devours the donkey" is an amusing translation, "the one who knows the gate/door" is the standard translation and makes a great deal more sense within the context of the sun god's nightly journey through the gates of the Duat.

Amun

Amun was one of the main manifestations of the creator sun god, the first of the gods. He, along with Ra and Ptah, were each in various myths, credited with creating the universe and being the divine light of creation. In one text they are defined as the same spirit - with Ra the face, Amun the spirit, and Ptah the body. To further support this, the Egyptians paired their gods together often and Amun is often commonly referred to as Amun-Ra. While he was originally painted with reddish skin, this was later changed after the revolution of Aten’s monotheism and its repudiation to blue skin, showing his connection to the air and being a primordial creation god. He was a god of air, the sky, the sun, as well as all things hidden.

Amun also is credited as being one of the Ogdoad (8 primordial beings - 4 pairs of male and female manifestations of abstract ideas). Sometimes he is referred to by the name Qerh or Nenu. As part of the Ogdoad he was a frog-headed god of air, said to represent invisibility, repose - but also quintessence, or the secret powers of creation. Amun, like the other creator gods, was said to have been self-created, rising from the chaotic waters of the Nun through his own willpower.

He was often symbolized as a man with the Amun crown which consisted of a flat-topped cylindrical crown base (called a modius) that was topped by tall, double ostrich feathers. The ostrich was a symbol of creation and light. He was also represented as the ram-headed sphinx, which was a potent symbol of fertility. Amun was sometimes referred to as "Lord of the Two Horns". In Thebes, there were 900 statues of the ram-headed sphinx. They were depicted with the body of a lion (never winged), the hooves of a ram or a goat, and the head of a ram. The ram-headed sphinx is called a criosphinx whereas the human-headed sphinx is called the androsphinx. Though, he was originally a minor fertility god, by the time of the New Kingdom, he was considered the most powerful, supreme god of Egypt and his worship bordered on monotheism. Other gods were considered merely aspects of him and his priesthood was the most powerful in Egypt. He was also called, “King of gods" and "Mysterious of form". He was the husband of Mut and father of Khonsu, the moon god.

Amun’s status changed drastically due to a religious revolution caused by the Pharaoh Akhenaten who decreed that the sun god Aten, was the only god of Egypt and forced the Egyptians to switch from a polytheistic religion to monotheism. He used the Egyptian military to destroy the old religion, targeting Amun particularly as he was nationally worshipped, throwing priests out of his temples and closing them, destroying them, or converting them to temples for Aten. Aten was worshipped for 16 years until Akhenaten’s death. His son, a boy-king, was forced by the influential priests of Amun to abandon his father’s home and change his name from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun. There followed under his rule a purge, an attempt to obliterate all traces of Aten and his father. The people returned to their old gods. During the New Kingdom, Thebes became the capital of unified Egypt and became known as “Niwt-imn" meaning "The City of Amun." Amun became the national god of Egypt and head of the state pantheon. Records show that during the New Kingdom, temples dedicated to Amun had over 80,000 people working for them and owned enormous amounts of land, cattle, and hundreds of ships. The Amun priests owned two-thirds of all the temple lands in Egypt and 90 percent of her ships plus many other resources.

Amunet (Amaunet) was one of the snake headed primordial goddesses of air who existed before creation. As a member of the Ogdoad (8 primordial beings that were 4 pairs of male and female manifestations) she was the female counterpart of Amun and as such was considered the mother of creation, mother, grandmother to the gods. She was the goddess of invisibility, known as ‘She who is hidden‘. The pair were also known as Quer and Queret / Nenu and Nenuit. In addition to invisibility, their names also imply they represented inactivity or repose.

Amunet was represented as a cobra snake, or a woman with the head of a cobra and was said to own the Tree of Life. She was later associated with the moon and occasionally in tombs, represented as a funerary goddess. Eventually she was absorbed into the myths of Mut, the mother goddess.

Amunet

Anat

Anat was a foreign goddess, adopted as the Hyksos immigrated into Egypt, and she remained after the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt. She was originally from Syria or Canaan. Anat was a warrior goddess of fertility, sexuality, love and war. She is sometimes called ‘Queen of Heaven’ and associated with the Egyptian native goddess, Neith. She is usually shown carrying weapons. In the battle between Horus and Set, Anat and the goddess Ashtart were given as allies to Set. In another telling, she was given as a consort to Set at the suggestion of Neith. In some texts she is a virgin goddess, while in others she is sensuous and erotic, and in yet others, she is called the mother of the gods. In some texts she is called ‘Bin-Ptah’, Daughter of Ptah. In some she is the daughter of Ra and as such, sister to Astarte. She is associated with Aphrodite of Greece, Astarte of Phoenicia, Inanna of Mesopotamia, and Sauska of the Hittites.

(Anedjti) Andjety was a prehistoric Egyptian god associated with fertility and the city of Busiris (Andjet) - a god of the ninth nome of Upper Egypt. His name, quite literally, means, ‘He who is from Andjet’. He was a god of the dead, possibly an early precursor to Usir or Osiris. He is associated with the djed symbol and was eventually absorbed into Osiris, so that his name became associated with Osiris.

Andjety

Anet

Anet (Ant, Int or Inet) is the name of the sacred fish, sister and companion to Abtu who swam with the solar barge of Ra. The two pilot fish were worshipped for protecting Ra - swimming on either side of the front of the prow of the sun barge as Ra sailed through the dark waters of Nun to sunrise, protecting it from any dangers of the underworld.

Anet was said to be a red fish, a tilapia, who would physically defend the boat with the gods accompanying Ra, after her brother Abtu loudly alerted them to the arrival and threat of Apep.

The tilapia fish was sacred to Ra and was one of his manifestations, its red color hinting at its solar association. The color red was also considered an aggressive protection against the dangers of traveling at night (much the way red ochre was used to protect shrines, and a red bull protected Osiris). The tilapia was also sacred to Hathor, the eye of Ra, and as such was important in funerary rites leading to resurrection.

In some cases, Horus and Ra (sometimes one sometimes the other) were said to themselves become the tilapia to defend the barge against Apep. This made the tilapia even more vitally important for the deceased who were traveling through the Duat.

A hymn said to have been sung by the Ogdoad to Amun-Ra makes reference to both fishes:

“…You navigate over your two heavens without an opponent,

your flaming breath has burned the evil one.

The red fishes are controlled by your boat,

the abdu fish has announced to you the wenti-snake,

the Ombite (Horus) has fixed his spear in his body. …“

See Abtu

Anhefta

A protective spirit who guards one end of the ninth division of Duat

Anhur

(Han-her / Inhert) Anhur was a warrior and sky god of Abydos who was believed to have originated in Nubia, on the far south of the Egyptian border, also known as Kush, now Sudan. He was usually shown as a man, sometimes painted with dark blue skin (like Amun) who wore a tall crown of four ostrich feathers. The ostrich was symbol of creation and light as worn by the Gods Shu and Amun. He was an Egyptian god of war, patron of the Egyptian army and royal warriors. Anhur was the model warrior to the armies of the Pharaohs and believed to be the "saviour" of those in battle. Also, he was known as a protector of travelers.

Anhur was know as Onuris to the Greeks and as a god of war, was associated with Ares. He was said to hunt and slay the enemies of his father, the sun god.

His name, which literally means ‘He who leads back the distant one’ (but also could be interpreted as ‘Sky Bearer’) appears to refer to the myth in which he is said to have journeyed to Nubia for the sake of bringing back the ‘eye of Ra’ - the lioness goddess who became his consort Mekhit. While this myth is strikingly similar to another, in which the god Shu brought back the fearsome ‘eye of Ra’ as his consort (this time as Tefnut) the literal translation of Anhur’s name suggests that the myth may have originated with him. Nevertheless, this did lead to Anhur being equated with Shu, as well as Shu’s connection to Ra under the epithet, ‘Son of Amun-Ra’.

Ani

A god of festivals

Anit

Wife of Andjety

Anpuit was a female counterpart to Anubis.

Anpuit

Anqet

Anqet (Anukit or Anuket) was known as the Embracing Lady, an epitaph for her role as a fertility goddess. She was also associated with hunting and childbirth and was thought to be a virgin goddess. A symbol associated with Anqet as the goddess of the hunt was the gazelle which was reflected in her title "Lady of the Gazelle", an animal that could be found grazing on the southernmost parts of the River Nile. Anqet was depicted in ancient Egyptian art with a crown of tall ostrich feathers which were the symbol of creation and light. The distinctive and unusual headdress is tied to her title as “Mistress of Nubia” as the style is very distinctive to African countries south of Egypt, worn by chiefs and male and female gods. The dwarf god Bes was also believed to be of African origin was also depicted wearing a similar crown.

Anqet was the goddess of the Nile cataracts and cultivated lands and fields. A cataract is a stretch of rocky islets, waterfalls, whirlpools, or white water rapids. There were six Nile cataracts, only one was in Egypt (Aswan) the others were in Nubia, now Sudan (aka Kush or Ethiopia). Anqet was a water goddess of the island Elephantine, and the cataract of the Nile River at Aswan. The cataracts were so dangerous that they were impassable except in seasons of high flood. The northernmost cataract of the Nile was on the border between Egypt and Nubia. Anqet was the goddess of all lands south of the Egyptian border and widely worshipped in Nubia, and given the title "Mistress of Nubia". There were no cataracts north of these to disrupt travel on the Nile in Egypt.

As the River Nile flowed towards the north, the annual flood waters entered Egypt by passing Elephantine and by the 18th Dynasty it became the cult center for the three gods: Anqet, the goddess of the cataracts, her mother Satet the war goddess of the flood or inundation and her father Khnum the water god who guarded and controlled the waters of the Nile. These three gods were the protectors of the River Nile and known collectively as the Elephantine Triad. As the Egyptian goddess of the treacherous Nile cataracts Anqet was particularly worshipped by the ancient Egyptian traders and sailors who left inscriptions on the rocks as a form of prayers to Anqet for their safe passage along the hazardous waters to Nubia or for their safe return to Egypt.

Elephantine was the capital of the state and for many years was the military stronghold of the Ancient Egyptian empire and a center of commerce and trade with the Nubians. The trading link with Nubia probably accounts for the name 'Elephantine' as there was a brisk trade in ivory at the island. The Nile god Hapi was believed to bring the silt to the banks of the Nile, making farming possible in the middle of the desert. It was believed that Anuket and the other two gods of the Elephantine Triad decided how much of Hapi's silt would be delivered during each year's flood.

The beginning of the harvest season, Shemu, was celebrated with the Festival of Anqet in which thanks were given for the harvesting of food crops such as wheat and barley, and industrial crops, such as flax and papyrus. Celebrations during the Festival of Anqet included a magnificent river procession, in which the other members of the Elephantine Triad, Khnum and Satet, were also honored. Statues of the gods were removed from the temple and ceremoniously placed on gilded ceremonial barques, equipped with long poles that were carried on the shoulders of their priests to the bigger river boats. The massive processions consisted of standard bearing Egyptian soldiers, priests, musicians, singers and dancers. Festivals were extremely noisy with shouting people, the chants of the temple choir, the blowing of trumpets, the beating of drums, the rattling of the sistra. The air would have been full of the smell of burning incense. Statues of other gods were added to the procession as different temples were passed. The people would enjoy the spectacle of the procession and celebrate with feasting. The people also gave offerings to the gods by throwing such items as jewelry and coins into the Nile to honor and appease the river gods.”

Anta

Anta was an aspect of the Mother Goddess Mut, worshipped at Tanis as the consort of Amun.

Anti

Anti was a Hawk god of Upper Egypt sometimes associated with Anat.

Antiwy

Antiwy, local god of the 10th nome of Upper Egypt has a name that is easily confused with Anty, the local god of the 12th nome of Upper Egypt. The main difference is that Antiwy is a duality of Anty. So if we were to read Anty as ‘having claws’ then we would read Antiwy as ‘the two having claws’.

The duality of Aniwy is sometimes represented as his name being written with two hawks in sacred boats. Sometimes, Antiwy is said to be the combined form of Horus and Set - embodying the bond created by their conflict.

Click for more!

Anubis was best known as a god of death, but it would be more accurate to say he was a judge of the soul. He would weigh the heart of the deceased against the feather of truth (Ma’at) and if it was as light as the feather, they could travel to the next life. If it was not, the heart would be fed to Ammit, a monstrous being, and the soul would be destroyed. He was almost always associated with a black hound or jackal and was one of the gods who aided Ra in battling off Apep each night.

*under construction*

“Anubis was depicted with the black head of the jackal even though real jackals are typically brown. The black jackal head of this jackal-god was characterized by its long, alert ears and a pointed muzzle. The color black was highly significant as it was a symbol of death, the color of rotting flesh, and symbolized the Underworld and the night. Black was also associated with the black soil of the Nile valley and as such also symbolized rebirth. There are many theories as to why the jackal was associated with Anubis. Some say it is because jackals were known to frequent the edges of the desert, near the cemeteries where the dead were buried. The first tombs were built to keep wild animals, like jackals, from desecrating the dead. Many statues representing Anubis were simply of a jackal upon a pedestal as seen in the beautiful examples from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Anubis was said to be the son of Nephthys and Osiris. According to Egyptian mythology Nephthys had made Osiris drunk, drawn him to her arms without his knowledge, and gave birth to a son, the jackal god Anubis.

His mother, Nephthys, left her son exposed to the elements. Instead of dying, he was found by Isis, who then raised him. He became the faithful attendant of Isis. He was credited with the invention of embalming, an art he first practiced on the corpse of Osiris. After Set had killed Osiris and scattered his remains, Anubis helped Isis and Nephthys to rebuild his body and presided over the first mummification He was associated with with the process of embalming and mummification. He conducted and guided the dead through the Underworld to judgment in the Hall of Truths. During the embalming process, the head priest-embalmers (the "Higher Mysteries") wore a jackal mask bearing the image of Anubis.

Apuat was another form of Anubis. In other instances, Apuat was another name for Anubis or Wepwawet, another

jackal-headed god.”

Anuke

Anuke, one of the oldest deities of Egypt, was an ancient goddess of war and was represented as a woman in battle dress, carrying a bow and arrows. She was at times shown as a consort to Onuris, god of war. Later, she became associated with Nephthys, goddess of death and to a lesser degree, Nephthys’s sister Isis. In some texts, Anuke is referred to as their younger sister. Eventually, she evolved into a nurturing, mother goddess who the Greeks associated with Hestia.

Apedemak

Apedemak was a war god of Southern Nubia. While he was unknown and not worshipped in Egypt, in Nubia he was depicted in an Egyptianized style - shown as a lion headed man, sometimes winged, holding a sceptre that usually depicted a lion or lion headed serpent. He was almost always shown wearing an elaborate hemhem crown, also known as the ‘triple crown’, the name of which means, ‘war cry’. It consisted of three atef crowns (or bundles) mounted on ram’s horns, with a uraeus cobra on either side. Additionally, the three bundles sometimes were depicted with three falcons surmounted by a solar disk perched atop them.

Apep (Apophis / Apothis / Apepi) was an immortal, cosmic, star-devouring being that the Egyptian gods battled each night to preserve our world. He was a giant serpent, said to have the body of a serpent and a head made of flint. Apep embodied chaos, darkness and nothingness - everything opposite of the ordered universe that the gods cared for and preserved. The monstrous Apep, was described occasionally as a huge crocodile but usually as a highly dangerous, gigantic snake who swam in the eternally dark waters in the “Secret Cavern” of the Underworld (Duat). He was known as the “Serpent of the Nile", the "Evil Lizard", "He who spits", "The Destroyer" and the "Eater-up of Souls".

Apep constantly threatened divine order and was the mortal enemy of Ra, the Sun God. It was said he had a pointed head which was shaped like a dart with fangs sank into the flesh of Ra, and the fire of their poison entered into the god. Ra, the sun god, represented light, warmth, and growth which made Ra the Sun god supremely important and Apep a deadly enemy of mankind.

Apep represented a demonic obstacle to the daily resurrection of the sun. Ra was believed to traverse the sky each day in a sun boat and pass through the realms of the underworld each night on another solar barge. During his nightly travels in the terrifying Underworld, Ra was attacked by the serpent god Apep. According to mythology the monstrous Apep, the god of evil, chaos and destruction, could swallow the waters of the river with his wide-open mouth so that the Sun Boat might be wrecked. Apep was believed to have supernatural powers and was able to use a magical gaze to hypnotize Ra and his companion gods.

Occasionally he would be victorious in his battles with Ra and his entourage of gods, and the world would be plunged into darkness. The ancient Egyptians believed that these victories allowed storms, darkness, rain and the terrifying eclipse of the sun to occur. They were afraid of cloudy days believing this forewarned them of a victory of Apep. The Egyptians believed that prayers, incantations and magic spell would help Ra and the gods in their endless nightly fight on their Sun Boat against Apep.

The ancient Egyptians were highly superstitious and feared that even the mention of his name would bring the unwanted attention of this evil god. This fear extended to creating images of Apep. Fearing that even an image of the god Apep could give power to the evil spirit, paintings and other depictions of Apep would always include another deity fighting to subdue the monster, or a scene in which the god had already been vanquished.

The terrible serpent god was also seen as a potential barrier to the souls of the dead succeeding in their journey through the Underworld to the Afterlife. The priests therefore created various spells and provided protective amulets and talismans to defend the souls of the dead against Apep on their perilous journeys.

Apep the evil destroyer was never worshipped, quite the reverse. Most temple rituals of ancient Egypt were aimed correcting chaos and restoring order to the world. Because Apep was immortal he was able to emerge unscathed from any defeats by the gods. It was therefore important to the Egyptians to offer prayers and spells to help the gods overcome Apep the evil serpent. The "Book of the Overthrowing of Apep" provided temple visitors with a spell for repelling negativity, which was symbolized by the solar god Ra defeating Apep. These rituals and incantations were enacted nightly by the priests and Egyptians and were thought to help ensure the victory of Ra in his life-and-death struggle with darkness.

In ancient Egyptian mythology there are legends concerning the defeat of Apep by a great cat. The cat goddess Bastet represented both the home and the domestic cat but was also represented in the war-like aspect of a lioness, lynx or cheetah. Cat Goddesses were revered for both their powers of protection and their skills as fierce combatants. Mau and Bastet, both cat goddesses, were credited with killing the evil snake god Apep.

Apesh

A turtle god

Apet

A solar disc wearing goddess worshipped at Thebes

Apis

Apis was the divine bull and was worshiped in Memphis as an incarnation of the god Ptah. The bull-god was believed to be the manifestation or living image of Ptah.

“The bull-god was also revered as the 'Herald' of Ptah, acting as an intermediary between the bull-god and the Egyptian people. He was believed to possess the powers of prophecy and considered to be an oracle. Food was offered to the bull and if it took the offering this was deemed to be a good omen.

A black bull calf with a white flash diamond shape on its forehead was considered to be the personification of Apis. This special bull was believed to have been conceived through a divine flash of lightening. The mother of the bull-god was known as 'Isis' in reference to the ancient Egyptian 'mother goddess'. They were kept in a sacred sanctuary called the Apieion. The palatial Apieion was built in close proximity to the temple of Ptah and consisted of two huge chambers, one for the bull and the other for his mother. The roof of the chambers were supported with massive statues of bulls. Both the bull-god and its mother were given the greatest care and fed with the finest food. Only the most honored guests were allowed inside the Apieion sanctuary.

The bull-god left the Apieion for special festivals and would form part of a great procession of priests, dancers musicians and standard bearers. There were jubilee festivals and rituals that involved the bull-god and the Pharaoh. At such festivals religious rituals were conducted in relation to the rejuvenation of the powers of the Pharaoh and the king accompanied the bull-god in the parade and is referred to as the "Race of the Apis bull".

The average lifespan of the bull was 14 years. There was only ever one bull-god. When the bull-god died the whole of Egypt went into mourning. The body of the bull-god was embalmed by priests and ceremoniously entombed in the Serapeum, the name of the vast underground necropolis where the Apis bulls were buried.”

Aqen

Aqen was a deity of the underworld, where it was said he guided the sun god, Ra. He was described as the mouth of time, from which the gods and demons pulled the rope of time.

Arensnuphis

Arensnuphis was a benevolent Nubian deity who was depicted as a lion companion to the goddess Isis or a man with a feathered headdress.

Asclepius

Asclepius (Aesculapius) was a Greek god of healing but was also worshiped in Egypt and identified with the deified Imhotep. His symbol, possibly derived from the god Heka, was a staff with a serpent entwined about it, associated in the modern day with healing and the medical profession, known as the Rod of Asclepius.

Ash - (As)

Ash was a Libyan god who was associated with Set and the Libyan desert, as well as oases west of Egypt. Depicted as a man with the head of a hawk, he was known as the ‘Lord of Libya’ and ‘God of Sahara’. Ash was a benevolent deity who provided the oasis to help travelers.

Astarte

Astarte was a goddess of the battlefield who wore bull horns as a symbol of power and was associated with horses and chariots. Like Anat, she was from Canaan and Syria, and was given by the goddess Neith to Set as a wife or companion. She was also said to have a relationship with Yamm, the god of the sea.

In one fragmented papyrus it tells of Yamm demanding tribute from the gods, Renenutet in particular, whose place is taken by Astarte. Of interest though, is that in the text Astarte was called, ‘daughter of Ptah’, associating her as Egyptian rather than Canaan, Syrian or Phoenician, where she was a a goddess of fertility and sexuality. The writing is destroyed on the rest of the papyrus, but the assumption is that their liaison tempered the arrogance of Yamm. Like Anat, she was sometimes called the Queen of Heaven. She was closely associated with Aphrodite by the Greeks, with Inanna/Ishtar by the Mesopotamian, and Sauska of the Hittites.

*under construction*

This goddess of Egypt was 'adopted' during the New Kingdom period of ancient Egyptian history from the war goddess Ishtar who was worshipped in Mesopotamia, Canaan and Syria. / During the rise of the Egyptian Empire the ancient Egyptians were influenced by the cultures of many other countries / She became one of the recognized goddesses of ancient Egypt during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period. / She was the Egyptian goddess of Horses and Chariots and venerated as a powerful and violent war goddess. / The Hyksos, meaning "foreign rulers", introduced the horse and the chariot to ancient Egypt during the 13th dynasty of Egyptian kings and by the 18th dynasty the expert use of the horse and chariot Egyptians had enabled them to rise to the peak of the Egyptian Empire. / The worship of Astarte the goddess of war, horses and chariots is understandable during this time and she was revered by Egyptian soldiers. / The aggressive nature of the goddess was represented by the bull horns that were associated with her in Egyptian iconography. / The priests of Egypt 'modified' the creation myth to include the war goddess and she was named as a daughter of Ra and the wife of Set. In certain areas of Egypt she was named as the daughter of Ptah. / Depictions of the goddess were similar to that of Hathor, in her war-like manifestation of Sekhmet, the lioness goddess who was said to breathe fire at the enemies of the pharaoh. Sekhmet was seen as the protector of the pharaohs and led them in warfare. / Her symbols were the lion, the horse, the chariot, the sphinx, and a star within a circle indicating the planet Venus which was also closely associated with Hathor.

The Egyptians practice of merging gods is called 'syncretism' which means the fusion of religious beliefs and practices to form a new system or to create a new god. / The goddess was also connected with fertility and sexuality, and many images of the goddess portrayed her as naked, especially in the Post Empire period of Egyptian history. /This goddess takes her place in history as the original of all figureheads depicted on sailing ships. / Like her counterpart Ishtar she was depicted wearing a headdress consisting of four pairs of horns topped by a disc. / She was associated with sexuality as she was said to have taken many lovers. The bawdy aspect of her attributes strongly appealed to the ancient Egyptian military.

Astennu

A baboon god associated with Thoth.

As the cause for one of the greatest religious and social revolutions to ever raze through Egypt, Aton is one of the most complex and controversial figures in Egyptian Mythology. Aton was a manifestation of the literal disk of the sun - before the pharaoh, Akhenaton decreed him as the one and only god of Egypt where he reigned as the monotheistic sun god until the pharaoh’s death, whereupon he fell back to his humble place alongside the pantheon of Egyptian gods before being eradicated completely.

Aton, the physical body of the sun, was represented as the circular disk of the sun with rays of light emitting downwards that ended in human hands. Aton embodied absolute power and was the source of all life. Aton was eternal, hymns proclaimed. He was beautiful and glorious and had created not only himself and his path across the heavens, but the heavens, the earth and every living thing as well. He maintained all life and determined its duration. All things came from Aton and all beings depended on him.

Originally, he was an aspect of the sun gods such as Ra and Amun - namely the disk of the sun where they resided. The term ‘aton’ refers to the literal circle of the sun and traditionally, the word was used as a noun which meant ‘disc’ referring to anything circular, and even the term ‘silver aton’ was used to refer to the moon and even the surface of a mirror. Eventually, though, the word evolved from meaning a literal disk to being an aspect of other solar gods. That, in turn, evolved into him becoming an equal creator god alongside them and then quickly into Aton meaning the one and only god.

Though Aton’s origins are obscure, traces show he was an obscure part of the worship of sun gods dating back to the Old Kingdom. Near Heliopolis, he was considered a form of the sun god and possibly had his own temple. Prior to Akhenaton, Aton was most often a symbol in which sun gods appeared. In a book of the dead based on Heliopolitan, Aton was mentioned in passages that show he was regarded as the physical body of the sun where Ra dwelt. It is a small step though, for the disk or the gods to become a god unto himself.

During the reign of Amenhotep III, Aton grew significantly in importance. Amenhotep III shared his father’s alarm at the power of the priests of Amun and shared his reverence towards alternate sun gods. This was encouraged by his wife Thi, a foreign woman said to have come from a town near Heliopolis who also may have been a votary of Aton before marriage. Together, they encouraged the worship of Aton, and alternate forms of solar worship were evident in their building projects, much to the chagrin of the priests of Amun-Ra. It was during his reign that Aton began to be worshipped extensively as a god, depicted as a falcon-headed man much like Ra. Their strong religious connection to Aton was passed at an early age to their son Amenhotep IV. It is believed that the intensity of his love for Aton and hatred of Amun-Ra was due to his mother’s influence.

*

Akhenaton (still named Amenhotep IV when he ascended the throne) succeeded his father without difficulty and for the first few years adhered to traditions, living in Thebes, offering sacrifices to Amun-Ra and appearing outwardly as a loyal servant to his namesake, Amun-Ra. Privately though, he worshipped Aton.

Akhenaton renamed Aton and the new designation upturned everything theologically in Egypt. As he elevated Aton above all other gods, the strain grew between Akhenaton and the priests of Thebes who declared Amun-Ra the king of gods. The mass of the population in Thebes sympathized with the priests. At growing odds with the priests and population of Thebes, Akhenaton began to build a new capital, Khut-Aton (Horizon of Aton) which included a palace for himself and homes for those who worshipped Aton and were prepared to follow their pharaoh there.

In the 6th year of his reign, he left Thebes and took up residence in his new capital. To further signify his severance of ties to Amun-Ra, he discarded his birth name “Amenhotep IV” (Amun is content) and became Akhenaton (Glory of Aton).

In the 9th year of Akhenaton’s reign, he changed Aton’s name once more, eliminating all mentions of Shu and Horakhty. The hawk-headed figure was no longer acceptable and replaced with the iconography of the solar disk with a uraeus and rays of light. Though this symbolism predated Akhenaton, it was now the sole manner in which Aton could be represented.

Upon changing Aton’s name, Akhenaton ordered the closure of temples dedicated to the worship of any other gods in Egypt. Persecution of the worship of other gods began and armies of stonemasons spread across the lands, scouring away the names, symbols, and images of other gods, most especially those of Amun. Even the plural form of the word ‘god’ was eliminated.

Aton was now lord of all, without the need of a goddess for companionship and without enemies who could threaten him. In the new capital, Khut-Aton, Akhenaton aggressively promoted Aton, proclaiming him the sole god. Akhenaton built his new theology on the bones of pre-existing solar-god theology which granted supremacy to the sun, ascribing it the symbolism of order, unity, and totality. Akhenaton’s worship of Aton was quite different from past worship of Aton though, which had been tolerant of other gods. Akhenaton’s worship of Aton was not.

In this new form, the nature of Aton became intrinsically monotheistic and incompatible with the idea of there being any other gods. He was ascribed the quality of oneness whose very nature refuted the existence of others. This new theology could only absorb or be absorbed by the pantheon of Egyptian gods as their existences were mutually exclusive. Atonism began as a henotheistic religion (religion devoted to one god while accepting the existence of others) but evolved into a monotheistic system.

Much of what we know of Aton is learned from Hymns to the god. They describe the wonders of nature and hail Aton as the absolute lord of all. When compared to the hymns of Ra we see aspects missing - most notably other deities. There is no mention of enemies such as Apep, Sebau, or Nak; no mention of Khepra rising or Thoth or Ma’at’s services. The hymns also contained none of the beautiful visions of life beyond death that are found in hymns to Ra. No longer were night and death the realms of Osiris and other gods, but rather simply the absence of Aton. They taught that night was a time to fear and that work is best done when the sun, Aton, is present. Aton did not have a creation myth, nor a family.

In Akhenaton’s hymn to Aton, Aton’s mannerisms are depicted, showing a love for his creations: “Aton bends low, near the earth to watch over his creation. He takes his place in the sky for the same purpose. He wearies himself in the service of the creatures. He shines for them all. He gives them sun and sends them rain. The unborn child and the baby chick are cared for. Akhenaton asks his divine father to lift up the creatures for his sake, so that they might aspire to the condition of perfection of his father, Aton.”

Inscriptions on temple walls regale the majesty and beneficence of Aton and representations of the visible emblem of the god were everywhere. He was depicted as the solar disk, from which rays of light stretch down, ending in hands that held the emblems of life. In these, the human-handed rays shone upon the king, queen, and their family. Despite a priesthood being devoted to Aton, it was only Akhenaton who could directly interact with the god; only he could know the will and commands of Aton. The god remained distant and incomprehensible to the general populace. It's quite possible the priesthood didn’t serve Aton so much as they did Akhenaton. The high-priest was even called the ‘Priest of Akhenaton’ indicating the supremacy of Akhenaton in his own theology and the effective barrier he formed between his priests and the god Aton. When one considers the conflict between the priests of Amun in Thebes with his family, it is possible this was as much a political strategy as it was theological. In carvings, Aton’s rays of light hold out eternal life in the form of ankhs to the royal family alone. Everyone else receives life from Akhenaton and his wife Nefertiti in exchange for loyalty to Aton.

During Akhenaton’s reign temples were also built to Aton across Egypt. His temples were unique in their design that left them uncovered open to the sky and sun, rather than the dark enclosures of traditional Egyptian shrines. Aton was worshipped in open sunlight. We don’t have precise information on the nature of the worship of Aton, but we know the practice was sensuous and materialistic. Incense burned frequently and hymns sung to Aton were accompanied by harps and instruments. People vied to bring gifts - fruits and flowers - to the altars, which were never stained with the blood of animal sacrifice as in other temples. Aton’s worship was joyous and practiced in bright cheerful spaces, painted in lively colors.

Artists employed by Akhenaton broke from old styles and indulged in new forms, colors, and treatments of the subjects they illustrated. The art in Khut-Aten advanced in a great leap forward - introducing shading and volumetric forms in their paintings, as well as an exploration into realism rather than symbols. These advancements in art styles did not last past Akhenaton’s reign however and it was only during this time that Egyptian artists worked with the effects of light and shadow in their work.

In the ninth year of his reign, iconoclasm was enforced when he banned the use of all idols, excluding only a solar disk with rays. He also made it clear that the image of Aton was but a crude representation; that the god transcended creation. Aton, by nature, was everywhere and intangible, therefore he did not have a physical form; as such, he could never be fully understood or represented. He was beyond creation. Later, even sun disk depictions of Aton were prohibited by Akhenaton. In an edict, he commanded that Aton could only be represented by phonetically spelling out his name.

For the last half of his reign, Akhenaton seems to have devoted himself to building his capital and cult, leading a prosperous life in his new capital, spending most of his time adorning it with beautiful buildings, sculptures and large gardens filled with every manner of tree and plant. It’s not known how old Akhenaton was when he died, though he was still a relatively young man. His rule did not last more than 20 years.

*

During his rule though, conditions worsened throughout Egypt. The furious priesthood of Amun-Ra fought to restore their god and themselves to rightful supremacy. Akhenaton’s death came as the opportunity they needed and they married one of his daughters to Tutankamun who immediately lifted the ban on worshipping the gods of Egypt. They began rebuilding what Akhenaton destroyed in Thebes, making peace with the priests and in proper time, returned the court to the capital of Thebes. Their reign was one of religious tolerance and Aton became but one of many gods among the reinstated pantheon. The return to the old ways was a popular one as most of the populace had not converted to Atonism and believed Egypt’s woes stemmed from abandoning the gods, who had abandoned them in turn.

Their successor, Ai, though he had been a follower of Aton, forsook all connection to Aton when he took the throne. After his death, anarchy followed and not much is known of this time. The XVIII Dynasty was broken and Khut-Aton declined rapidly after Akhenaton’s death. By this time its population left and the deserted city was pillaged for its beautiful white limestone.

When Horemheb came to power under the hand of the priests of Amun-Ra, he used his power to eradicate every trace of worship to Aton. Amun-Ra had conquered Aton. Thebes was once again the capital of Egypt. The priests of Amun-Ra had reclaimed their power. Less than twenty-five years after the death of Akhenaton his city was empty, his temples desecrated, his followers scattered and his enemies ruled the country. Aton fell into obscurity.

*Atum

Atum (Atem or Atmu / Tem or Temu) was another manifestation of the creator sun god. Unlike Ra, Amun and Ptah who were usually associated with the sun at the height of it’s zenith and power, or Khepra who was associated with the rising sun - Atum was associated with the setting sun. Atum was considered the first god, self-created from the waters of Nun. His name means the complete one, and he was said to also be a woman, known as the great he-she and as such, was able to create the universe by making love with his shadow. He was said to have created the first pair of gods - Shu and Tefnut. But Shu and Tefnut left him to explore the universe, and Atum was lost in despair with loneliness and fear of being alone forever. When Shu and Tefnut returned, he was so overjoyed, he wept tears of joy that turned into the first human beings.

Though he was a creator god, who helped battle off Apep each night, he also told Osiris in the book of the dead that eventually he would destroy and submerge the world back into the darkness of the waters of Nun - and only he and Osiris would survive in the form of serpents.

*under construction*

Atum, the Egyptian solar god of creation, the first of all the gods and the 'father of the Pharaohs. Atum emerged from the primeval ocean of chaos called Nun as the sun god at the beginning of time and was the creator of the world. According to ancient Egyptian mythology and their creation myth Atum spat out the elements of moisture and air that became the Goddess Tefnut and the God Shu. The sun was thought to have been a primary factor in the process of creation and so Atum was worshipped as a solar deity. Atum was later subsumed as the Ra, the Supreme Solar God is also closely associated with other ancient gods.

Atum was the first god, the Egyptian solar god of creation, god of the setting sun and 'father' of the Pharaohs. The Pharaohs of Egypt claimed descent from him and this connection is reflected in images of Atum in which he is depicted wearing the crowns or the headdresses worn by the Pharaohs.

As the culture of the Egyptians developed some of their older gods were subsumed (meaning absorbed) into newer gods. This practice is called 'syncretism' which means the fusion of religious beliefs and practices to form a new system. The Egyptians combined different deities into the identity of a single entity. The names of these composite gods were linked, creating names such as gods such as:

Atum-Ra - the sun god

Atum-Khepri - connected with the rising sun, the scarab beetle and the mythical creation of the world

Atum-Horus - the solar god and protector of the monarchy

The name of Atum was eventually dropped and these gods were known by their new single names. The practice of syncretism, where an old god combines with a new god, causes significant confusion as the attributes and symbols associated with the older god merge into those of the new god. This results in Atum being closely associated with Ra, Khepri and Horus and his symbols change and expand according to the beliefs of the time. He is therefore referred to as embodiments of the newer gods

Each of these gods were solar deities, or sun gods:

Atum was the setting sun which travelled through the underworld every night

Khepri was the rising sun

Horus the solar god of god of the east and the sunrise

Ra was the midday sun

Ra-Harakhte was the winged solar disk

He was therefore identified with the setting sun who had to be regenerated during the night, to appear as Khepri at dawn and as Ra at the sun’s high point.

Auf-(Efu Ra)

Auf was the night aspect of the sun god Ra. He was a ram headed god who wore the solar disk and traveled at night through the Underworld waterways in the solar barge, traveling to reach the east in time for the new day. Through the night, he had to fight off the creatures of the underworld, while gods and demons pulled his boat. Auf stood in a deck house, while the serpent Mehen coiled above, warding off Apep who sought to devour the sun each night. The boat of the night was guarded also, by Hu, Saa, and Wepwawet.

Ba

A god of fertility

Ba’al

Ba’al was a Semetic sky god of storms and thunder, originally from Phoenicia, whose name means ‘Lord’. He was a major deity in Canaan, and only in the later period of the New Kingdom, was he worshiped in Egypt.

Ba’alet

(Ba'alat Gebal) Ba’alet was a Phoenician goddess and patroness of the city Byblos whose name meant Lady or Mistress. She was a protecting deity who became incorporated into Egyptian mythology due to her being associated with papyrus, which was imported into Egypt from Byblos.

Babi

He was an ancient deity, older even than most of the Egyptian pantheon, dating back to the Old Kingdom. His name translates as ‘bull of the baboons’ or ‘chief of the baboons’ - the dominant male. The Ancient Egyptians had strong opinions regarding baboons. Baboons are extremely aggressive and they were a symbol of high libido, violence, and frenzy. Accordingly, Babi was seen as a bloodthirsty being, living on entrails. Babi was a fierce, bloodthirsty god of virility who was depicted as a hamadryas baboon and symbolized male sexuality. His supernatural aggression was said to be a trait monarchs aspired towards. Unlike most other Egyptian deities, he stood out for his violence and his fury. He represented destruction.

Baboons were also believed to represent the dead, and in some cases, they were said to be the reincarnation of ancestors. Because of that, baboons were associated with death and with the affairs of the underworld. As such, Babi was a deity of the underworld, the Duat, and an executioner. Some sources say that he devoured humans to satiate his bloodlust. In other accounts, he was said to devour the souls of the unrighteous after they had been weighed against Ma’at - thus was said to reside by a lake of fire, representing destruction. This judgment was an important part of the underworld and as such, Babi was said to be the first-born son of Usir - who was the god of the dead in the regions that also worshipped Babi. In other areas, he was said to be the son of Osiris, in Osiris’s role as god of the dead.

His phallus is represented as, not only the mast of the underworld ferryboat, but also the bolt on the doors of heaven - crediting Babi with control of the darkness, opening the sky for the king. Not only was he credited with being able to control the dark waters, but also to ward off snakes. His symbol of virility is included in a spell where a man wanting to ensure his ability to have successful intercourse in the afterlife, identifies his sexuality with Babi. The Egyptians worshipped him not only to appease the violence he represented, but to have sexual virility in both life and death.

Banebdjedet

(Banebdjetet) Banebdjedet was a horned, fertility god of lower Egypt who appeared either as a ram or most notably - a man with four ram heads to represent the four Ba's (souls) of the first four gods to rule over Egypt: Atum, Shu, Geb, and Usir. In Egyptian, the words for soul and ram sounded identical, and ram deities were often regarded as the appearance or soul of other deities. He was the consort of the fish goddess Hatmehit and was associated with the city Mendes, which eventually became another name for Osiris.

One myth tells of when Horus and Set battled for the throne of the gods and Egypt, Banebdjedet leapt between them in the final battle and demanded a peaceful conclusion, arguing that if the god's abandoned Ma’at, it would result in universal disaster. He argued that the gods should consult with Neith and rely on her wisdom. Neith ruled that Horus was the rightly ruler, being the son of Osiris and that Set’s attempt to take the throne through violence and treachery invalidated his claim.

Ba’Pef

A little-known underworld deity; ram-headed god of the eighth hour, Ba’Pef was a god of terror, specifically spiritual terror. ‘Ba’ translates as soul and his name means, ‘that soul’. This obscure, malevolent deity was said to reside in the House of Woe in the afterlife and cause afflictions to the pharaoh. Though there existed a cult to help appease Ba’Pef and protect the pharaoh, he was never worshiped or had a temple.

Bastet was a particularly beloved goddess, and families would invite cats into their home, inviting the spirit of her with them. The cats would protect the family from snakes and rodents, as Bastet protected them from evil spirits and contagious diseases (especially those related to women and children). So revered were cats because of her, that they would be mummified and families would be buried with their cats. She also represented fertility and sexuality - women would buy amulets and statues of her with kittens to assure their own fertility. She was a protector of hearth and home from both misfortune and evil.

Originally she was Bast, a fierce lioness closely paralleling the myths of Sekhmet, but when Egypt unified, she added the diminutive ‘et’ to her name and became the tame house-cat. She was also closely associated with Hathor, who like Sekhmet and Bastet was referred to as the daughter of Ra and the ‘eye of Ra’. So adored by the Egyptians was Bastet, that the Persians used that devotion to win the Battle of Pelusium by painting images of Bastet on their shields and driving cats in front of their army, knowing the Egyptians would rather surrender than offend their goddess Bastet.

Bat

Bat was an ancient, celestial, cow goddess associated with fertility and success, particularly in Upper Egypt. She was one of the oldest Egyptian goddesses, dating back to the early Predynastic Period (6000-3150 BC) and was eventually absorbed by Hathor who took on her characteristics, so that Bat became considered a permanent aspect of Hathor. Bat is usually depicted as a cow or woman with cow ears and horns. She is rarely depicted in Egyptian art, though she is likely the image at the top of the Narmer Palette as she was credited with the King’s success. Bat is found more often though in jewelry and amulets where the head is human, but bovine ears and horns grow from her temples. Her body is shaped in a way that suggests the sacred rattle, or sistrum. This is particularly fitting, since her cult center was in a district of Upper Egypt known as the ‘Mansion of the Sistrum’. It was said she blessed people, using her ability to see both the past and future.

Bata

Bata was an Egyptian god associated with the 17th Nome of Upper Egypt, along with his older brother Anubis. Originally, he was represented as a ram, but following the 18th dynasty, he was represented as a bull. One myth tells the story of how he and Anubis worked the fields together until Anubis’s wife tried to seduce Batu who refused her. Scorned she tried to turn Anubis on his brother, saying he had tried to seduce and beat her. Anubis set out to kill Batu, who escapes over a crocodile infested river where he is able to plead his innocence to his brother Anubis by cutting off his own genitals. He tells his brother he is leaving, but that his heart will be hidden in the highest blossom of a ceder tree. If ever Anubis should see his beer froth, he will know to come find his heart and return Bata to life. Anubis returns home and kills his wife.

Bata leaves and begins life anew, when the gods of the Ennead take pity on him and fashion him a godly wife. But his wife is seduced by the pharaoh and she has the ceder tree cut down, leaving Bata dead as she marries the Pharaoh. Anubis sees the froth in his beer and searches for years to find his brothers heart. He follows Batu’s instructions and returns his brother to life in the form of a bull. Batu travels to his wife, who recognizes him and his him killed yet again. Two drops of his blood fall to the ground and sprout as Persea trees. His wife cuts those down, and makes furniture and utensils with them, but manages to get a liver in her mouth and becomes impregnated with Bata’s child. She gives birth to a son who is a resurrected Bata, who becomes crown prince and eventually pharaoh. He appoints his brother Anubis as his crown prince and the rule Egypt together.

*Bennu

**entry under construction**

The Bennu bird was said to be a self-created being that was said to have flown over the primeval waters of chaos, the Nun, before creation. Where the waters receded at the beginning of time, it was believed that the Bennu had sacred pillars known as Ben-Ben stone where the blessed bird rested. The same primeval mound where creation began was said to have also been the birth place of the Bennu, and where it’s cry broke the primeval silence, marking the beginning of creation and time, making it the god of time. It’s cry was said to have determined what could and could not exist in creation.

The Bennu bird was depicted as a heron and was the myth that inspired the Phoenix.

The Bennu phoenix was also linked with the inundation of the Nile and the creation of all.

Bes

Bes was a fat, bearded dwarf god of music, play, and warfare - ugly to the point of being comical, with bow legs, an oversized head, goggle eyes, bushy tail, and large feathered headdress. He is often shown sticking out his tongue and holding a rattle. He was a god of humor, song, and dance, but also infants and childbirth.

As an apotropaic household protector, his statue was commonly put up in the home, often shown wearing a soldier’s tunic, appearing ready to launch an attack on any evil. He was responsible for many tasks, such as scaring away demons and evil spirits, killing snakes, guarding children - and even aiding women in labor by fighting off spirits - thus he was present with Tawaret at births.

The images of him, that were kept in homes, were quite different from those of the other gods. When carved or painted on a wall, he is never shown in profile, but always full-face, almost unique in Egyptian art. Normally Egyptian gods were shown in profile, but instead, Bes appeared in full-face portrait. There are also depictions of Bes with feline or leonine features.

Representations of an almost identical dwarf-god became widespread across the Near East during the first millennium BC and are common in Syria, Palestine, and Arabia. This god's name in Assyrian and Babylonian may have been Pessû. Bes seems to have been the only Egyptian god who became widely worshipped throughout Mesopotamia.

Besa

The spirit of corn

Beset

Beset was the female aspect of Bes. As Bas was a protective god, his female aspect was called on in ceremonial magic to ward off dark magic, ghosts, spirits, and demons.

Besna

Goddess of home security

Buchis

Buchis was the deification of the Ka (life force) of the war god Montu in the form of a living bull. Buchis was depicted as a running bull.

Cavern Deities

The Cavern Deities are a group of nameless deities who are usually represented as serpent-like beings who lived in caverns in the underworld. They would punish the wicked souls by beheading and devouring them, but they would also aid the justified dead. In the “Spell of the Twelve Caves” (the 168th spell in the book of the dead), it is told which offerings should be left for them. In honor of them, the Egyptians would leave offerings near caves for them.

Dedun

(Dedwen) Dedun was an anthropomorphic god of Nubia, who was at times worshiped in Egypt. He presided over Nubia and their access to resources such as incense. The royal aroma, in the Pyramid Texts, is of incense brough by Dedun for the gods, and Dedun was said to burn incense at royal births.

Denwen

(Denwin) Denwen was a fiery ancient serpent deity represented in the form of a dragon surrounded in flames. He held power over fire and was said to be so powerful that he would have caused a conflagration destroying all the gods with his breath of fire - but he was overpowered by the spirit of a dead king who saves all of creation.

Djebuty

A tutelary god of Djeba. (A tutelary is a minor-deity or spirit who is a guardian or patron of a particular place, person, lineage, nation, or occupation.)

Djefa

God of abundance

Dua

God of toiletry and sanitation

Duamutef

Duamutef was one of the Four Sons of Horus and was a protector god of the canopic jar containing the stomach. He presided over the east, had the form of a jackal, and was watched over by the goddess Neith.

The jackal is linked to Anubis and the act of embalming and also Wepwawet the "opener of the ways" who seeks out the paths of the dead. Duamutef’s role seems to have been to worship the dead person, and his name means literally "he who worships/adores his mother". The most common cause of death in war, was from injuries to the torso and stomach. Duamutef, who guards these organs, was associated with death by war and his name could also mean, ‘adoring his motherland’.

In the Coffin Texts, Horus calls upon him, "Come and worship my father N* for me, just as you went that you might worship my mother Isis in your name Duamutef." Not only was Isis the wife of Osiris and mother of Horus, but she was also the consort of Horus the Elder and thus the mother of the sons of Horus.

This ambiguity is added to when Duamutef calls Osiris, rather than Horus his father, although kinship terms were used very loosely and could mean descendant or ancestor rather than son or father. In the Book of the Dead Duamutef says, "I have come to rescue my father Osiris from his assailant ." Though the text does not specify who might assail Osiris, there are two main candidates: Set, the murderer of Osiris or the other possibility is Apophis, the serpent demon who prevents the Sun's passage and thus the resurrection of Osiris. Either way, Duamutef through his worship of Isis has the power to protect the deceased from harm.

Dunanwy

Dunanwy was said to have been the deity associated with the East, and was usually depicted as a hawk and refereed to as - He of the outstretched ‘wing’/’claw'. In the Pyramid Texts, the four cardinal points are represented by different gods - Thoth with the West, Seth with the South, Horus with the North and Dunanwy with the East. There has been some speculation that Dunanwy was not originally conceived of as a hawk, but rather a cheetah, possibly shown with wings to convey the idea of speed, or even representing a griffin.

This idea may have contributed to the symbolism of the Eye of Horus, the Wadjet, in that the eye is said to have incorporated elements of a human eye, a hawk eye, and a cheetah eye - elements that all have been fused together in Dunanwy.

Edjet

Edjet was a minor goddess, sometimes treated as a less common form of Hathor or Bast. She was depicted in the form of an ichneumon, an Egyptian mongoose. Her name specifically means female mongoose - though it also has connotations with ‘to be safe’ ‘to be whole’ as well as ‘to perceive’. As such, she was the savior, as well as the perceiver.

In several texts, she is credited, as Hathor, with killing Apophis. One Hymn of Hathor acclaims, “Edjet (who) killed Apophis in her form of a young predator.” and elsewhere, a caption states of Hathor, “You are ‘The Great One’ {Edjet} having killed Apophis in your form of a young predator” {The name placed here appears to be a byname of Edjet.}

Edjet could also be the consort of Herishef and as such, ‘Mistress of Herakleopolis’. In addition to her victories against Apophis, she was also entrusted according to Herakleopolitan tradition, with protecting a plant (possibly the caster oil plant) that was associated with the resurrection of Osiris. There is also evidence of the importance of worship of the mongoose at Herakleopolis.

Edjet may also have shared a festival with Bast and there, she appears interchangeable with Bast in the rite of sacrificing the oryx.

The Ennead

**entry under construction

An extended family of nine deities produced by Atum during the creation of the world. The Ennead usually consisted of Atum, his children Shu and Tefnut, their children Geb and Nut, and their children Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys

*

After Atum, the four deities (Shu, Tefnut, Geb, and Nut) established the Cosmos, whereas the second set of deities (Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys) mediated between humans and the cosmos.

The Ennead were the nine gods said to have

The nine gods worshipped at Heliopolis who formed the tribunal in the Osiris Myth: Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, and Set. These nine gods decide whether Set or Horus should rule in the story The Contendings of Horus and Set. They were known as The Great Ennead. There was also a Little Ennead venerated at Heliopolis of minor deities.

According to the Heliopolis doctrine, Geb came from a line of important gods. His parents were Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture, who were in turn the children of Atum. Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys were the children of Geb and Nut, and together these gods made up the Heliopolitan Ennad. After Atum, the four deities (Shu, Tefnut, Geb, and Nut) established the Cosmos, whereas the second set of deities (Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys) mediated between humans and the cosmos.

Esna

A divine perch

Fa

A god of destiny

Fetket

Fetket was an Egyptian deity who cared for the inhabitants of the hereafter, responsible mainly for providing for the needs of the sun god, Ra, and the deceased pharaoh - though he also cared for the less prestigious dead. In the ‘Texts of the Pyramids,’ he would pour their drinks and hold the function of the cupbearer, serving as a butler to Ra, providing him with their drinks. A such, Fetket is the patron god of bartenders.

An interesting variation puts him as head of the divine household, “O you, Kitchen Masters and Drinking Attendants, recommend Téti [the deceased] to Fetket, the cupbearer of Re, whom Re recommends Téti to the Masters of Supply. When he bites, that he gives to Téti, when he sips, that he gives to Téti.”

Forty-two Judges

The judgement of the soul in the afterlife took place in the Hall of Truth (or the Hall of Two Maats - The double or twin Maat means the presence of extremes. In this context, the term sometimes used is the ‘Hall of Two Truths’. Two Truths refer to the dual construction of all things. For instance, there cannot be a poor man unless there is also a rich man.)