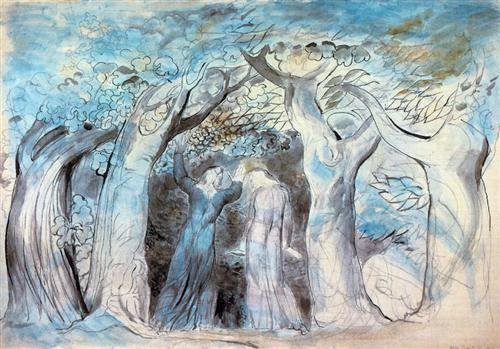

Illustration to Dante's Divine Comedy, Hell, by William Blake.

William Blake (1757-1827) lived most of his life in London, with a short spell on the Sussex coast, during which he was charged with sedition because of what he said to a soldier and for which he was put on trial. His life spanned the turbulent years that saw the independence of the American colonies and the French Revolution, both of which inform his prophetic understanding of history.

Blake’s two prophecies, America and Europe, were ‘prophetic’ not because Blake sought to predict what was going on—indeed they were written following these events. Rather, he sought to plumb the depths of the historical and social dynamics which were at work in them. He was part of a tradition of radical non-conformity in English religion, with different ways of reading the Bible.

In many ways Blake is an obvious choice of someone whose life’s work was to link ‘the personal and the political,’ but his work for justice and equality in the world was less through political activism or a practice which seeks to bring about societal transformation, and more about the intellectual task of changing hearts and minds. His Descriptive Catalogue of 1809 indicates that he wanted to make a pitch for a role as a public artist. But his exhibition met with the derision of the only reviewer of the exhibition (Robert Hunt), who disdainfully dismissed it as a “farrago of nonsense ... the wild effusions of a distempered brain,” and Blake as “an unfortunate lunatic.”

This initiative on Blake’s part not only shows his sense of vocation but also the difficulties which attended the reception of his work. His illuminated books are as challenging today for the reader or viewer as they were when they were first published, and there will be many who continue to react like Hunt. But this complexity only underlines the difficulty of the interpretative tasks Blake undertook as he explored relationships to the past, and the cul-de-sacs which can so easily attend the journey of personal and political transformation.

Throughout his work he remained committed to the following task as expressed in the Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is: infinite.” Arguably, all of Blake’s works are designed to facilitate the process of change in the individual and in society. Transformation is key to everything he undertook.

This takes many forms. In his early works Blake sought to prioritise the “Poetic Genius, the Spirit of Prophecy,” in order to ensure that people don’t end up repeating the “same dull round over again.” He challenged the pervasiveness of ways of thinking in culture and society which separate and condemn. As far as Blake was concerned, “Without Contraries is no progression.” Any neat separation into sacred and secular, for example, is questioned, as is the perennial tendency to negate difference rather than accept it.

“I pretend not to holiness! yet I pretend to love,” Blake wrote in Jerusalem. It comes as no surprise therefore that he came to see the forgiveness of sins as fundamental to a life in which difference and ‘the Other’ are sources of creativity rather than reasons for rejection, aloofness or suppression. In Blake’s later work, the complex effects of the “two contrary states of the human soul” are teased out in a quest for personal and social integration.

This quest reaches its climax in Jerusalem. Blake believed that he wasn’t writing “Poetry Fetter'd” in this masterwork. Instead he offered words and images which addressed the national torpor, thereby initiating a necessary and long drawn out process of awakening, with all its false starts and attendant difficulties—an arduous journey towards the fulfilment of the hope that “Heaven, Earth & Hell, henceforth shall live in harmony.”

If the balance in Jerusalem tilts more towards text rather than images, the later Illustrations of the Book of Job prioritise images over text. Blake reads this biblical book in terms of the transformation of an individual who is locked into the habits of received wisdom by the disturbing experiences of life and vision. These experiences enable people to see the divine within, and to demonstrate their redemption through the practice of love for their enemies.

According to Blake, that meant the “annihilation of Selfhood”—by which he didn’t mean self-denial but recognising that true human flourishing is possible when we realise that “every kindness to another is a little death In the Divine Image nor can Man exist but by Brotherhood.” It also means allowing “the Poetic Genius, the Spirit of Prophecy,” full rein to do its work, rather than co-opting it into promoting a self-centred ego trip. The promotion of a cause, however worthy, can lead to its betrayal when the ego attaches itself and becomes the very opposite of poverty of spirit, fuelled by self-righteousness and self-promotion.

Blake stressed the importance of the imaginative engagement of the reader or viewer—meaning anyone, not just the academic elite. All could allow the “Poetic Genius” within to stir them into an imaginative engagement with life through human relationships as well as self-understanding. His attempts to expedite human transformation in this way anticipate many modern movements such as Latin American liberation theology.

This movement was a central part of the resistance to military dictatorship in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s, especially in Brazil. It played a key role in preparing a wide-ranging pastoral programme of support and accompaniment to those living in favelas on the margins of large conurbations like São Paulo. The starting point of liberation theology was the centrality of human experience: the reality of life was key to the interpretation of the Bible and church tradition. Popular education materials embraced the importance of images as well as texts, and formed important components of pastoral programmes in many Brazilian dioceses.

Liberation theology was inspired in part by the work of the distinguished educator Paulo Freire (1921-1997), who stressed the links between learning and action, experience and reflection. He criticised a view of education in which students become mere accumulators of information or depositories of knowledge. Ordinary people were encouraged to allow their experience to inform their reading of the Bible, and to draw on their insights and experiences.

As Carlos Mesters puts it (a theologian based in Brazil), “the emphasis is placed not on the text itself but rather on the meaning the text has for the people reading it...Life takes first place!…ordinary people are showing us the enormous importance of the Bible; and at the same time its relative value—relative to life.”

Similarly, Blake’s concern throughout his work was the interaction of all aspects of human experience, exploring how they were connected and showing that working with one required working with all the others. To this end he drew on many resources, including the Bible, though he was very much aware of its weaknesses as well as its strengths.

In words that lead up to what has become England’s unofficial national anthem, the so-called Jerusalem (in fact the Preface of Milton: A Poem), Blake advocates the “proper rank” of “the Sublime of the Bible,” where “Inspiration” gains priority over “Memory.” His aim was to restore the balance of power, whether in society or in one’s personal life.

Justice and love, the personal and the political, need to be in a dialectical relationship if they are to ensure transformation rather than stagnation or oppression.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.