2002 - The millennial Mac: iBook G4 "Snow"

Previous article:

You might be wondering at this point why I opted for the iBook G4 and not the instantly recognisable and iconic iBook G3 "clamshell" in finding a turn of the century machine to test. Well, it's simple - I own two of the translucent multi-coloured plastic iMacs and I use them in contempt as the stands for my coffee-table. I simply can't think of something artistic to do with the iBook G3, and certainly couldn't see any way I'd ever actually use it after my research. This is, after all, a quest for the perfect Apple laptop, and frankly, the clamshell G3 was at most ever a toy. While the rich-kids at school all had PowerBook G3s, the rich-kids at uni had PowerBook or iBook G4s (their younger siblings, especially the pre-teen ones might, admittedly, have been clamshell G3 users). I may yet buy a clamshell one day to complete my collection, but I'd have to find a bargain as on eBay they now fetch far more than they are surely worth. That, and, it's almost impossible to find one in mint condition. Even the ones that look like they've been looked after are badly cracked. These were of an age of laptops that were not particularly well-designed nor well-made. Be forever warned buying technology as a fashion accessory!

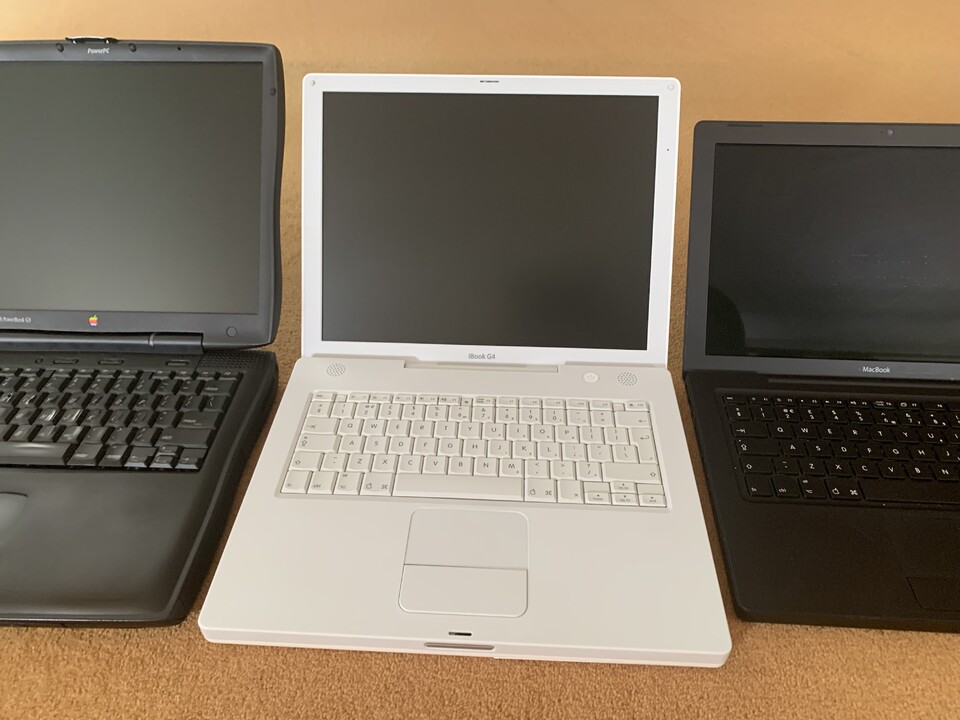

My iBook G4 is also neither well-designed nor well-made, but has one redeeming quality which we'll come on to later. What's most surprising about it though is how little it's aged in 20 years. While all modern Apple laptops are variations of silver, the black and white laptops of the early 21st century certainly stand out, but are not out of place. You can see clearly in the design of the iBook that Apple was really wrestling with the format for the modern laptop, and they very nearly get it right. So much so in fact that the iBook has so many recognisable features that carry through to their range of today.

While not as powerful as the contemporaneous PowerBook G4 range, the redeeming quality of the iBook is found in its weakness turned into its strength. While I was praise-ful of the G3 that if well looked after it would work just as well today as new, this would not be true of the iBook if commercial software companies are given their way. The problem is less at this stage with Apple rendering the device obsolete, and more about those who supplied applications which were increasingly getting tethered to internet services to run. The challenge with the iBook is that it shipped with MacOS 10.3 and was only compatible up to MacOS 10.5. Later operating systems won't work on it, and given its PowerPC architecture, rather than the Intel chips that Apple later went on to base their computers around; made it unattractive for software companies to support. Thus, you have to look harder to find software that will run on the iBook, and not just that there is a limited range of applications - but most of them have been withdrawn from internet repositories making it very difficult in getting such a machine up, running, and productive.

I was about to write off the iBook, when I made a discovery in a small corner of the web that has kept me very interested the last few months, and I suspect a few years to come as well!

That corner of the internet is the community of people who are fans of the Amiga platform from the mid-1980s. Amiga started out as a spin-out project from some engineers at Atari which was a famous computer game, arcade machine, and home computer manufacturer that peaked in the late '70s and early '80s. Computer graphics of this era were very primitive compared to what we are familiar with today, but progress was rapid, and machines were vying for primacy in their ability to display and manipulate graphics. The Amiga engineers knew this and realised that if they could create a machine which leap-frogged the competition in this regard, they would have a big commercial success. While they had an agreement in principle with Atari that Atari would base their next-gen machine on the Amiga design, Atari was not a particularly well-run company and, to make things worse, were about to import a CEO from their closest rival, Commodore, which would result in a shift in strategy and focus.

Commodore's story is a fascinating one: Jack Tramiel (Trzmiel) was a holocaust survivor and emigrant to the United States. After the war he served in the US Army, and on demobilising started an electronic equipment company that specialised in repairing, and subsequently, manufacturing office equipment, most notably, calculators. In search for a name for his enterprise, he settled on 'Commodore' - the name resonating trust, dependability, and authority from his military experience. By the early 1980s, Commodore also had a successful home and commercial computer business also, and the 1978 Commodore PET is one of the most iconic designs of that era (and if you look closely if you're ever on a Zoom call with me, you might just see one in the background)! Things would have been going well for Jack other than he had a difficult relationship with one of his financial backers, and there was a disagreement over that investor running personal expenses through the Commodore business. Jack ended up leaving and joining arch-rival Atari, and the new guard at Commodore knew they needed a bold move if they were to compete against Jack's genius and Atari's strong heritage.

It was therefore a major coup that they seduced the Amiga team across to Commodore and away from Atari. There are some great accounts of the detail in books like Tim Danton's Computers that Made Britain which go into a level of detail beyond the scope for this article, but in short - Commodore pulled a fast one, and then worked their socks off to release the Amiga, betting the ranch that the machine would live up to its promise and the superior graphics lead to the commercial success they desired.

While the first machine, the A1000 was an incredible achievement for its day, they didn't quite get the formula right until the next version (the A500 for home users and A3000 for business). If you grew up in the 1980s or early 1990s the chances are the A500 might have been your first computer. It was a massive commercial success all over the world and led to follow-up machines such as the iconic CDTV, A600, A1200 and A4000. Sadly, at this point things started to go wrong again for Commodore. Commercial missteps, combined with reliability problems, and slipped deadlines all conspired to leave the company faced with bankruptcy in the mid-1990s. And just like the hundreds of other flash-in-the-pan companies of the early microcomputer era, Commodore and the Amiga platform would have remained a historical curiosity if it were not for the efforts of their user base and, I'd argue - an unintended consequence of a design choice by Apple.

The second pillar of the story that leads us to the iBook's redeeming quality stems from the evolution of processors that Apple ran in the 1980s to 1990s. As I described in the third instalment of this series, there were five main choices presented to computer buyers in the mid-1980s, but by the mid-1990s only two remained: the Apple ecosystem, or the 'Wintel' one dominated by IBM PC-compatible machines with Intel processors running Microsoft Windows. And the problem for Apple was that they were falling behind.

While the 68000 chip from Motorola in the original Macintosh was a great choice that led to some real differentiation in the platform in the early days, by the 3rd and 4th generation of that processor, it was really starting to show its limitations especially when compared against the raw power offered by Intel. Motorola was heavily reliant on Apple's business by this point as many of its other customers had taken each other out during the frenzy of the 1980s home computer bubble. Realising that they needed a way of securing Apple's business, on learning that Apple and IBM were in partnership to design a next-generation processor, Motorola spotted an opportunity to bring not just their experience with chip fabrication to the party, but also in giving Apple the opportunity to migrate to a modern platform with minimum compatibility issues with their previous product line. The PowerPC chip architecture was born, a three-way alliance between Apple, IBM, and Motorola and importantly, a credible alternative to Intel's dominant x86 line and the new 'Pentium' processor that was to mark the step-change for that ecosystem.

I've long forgotten what happened with the first two generations of PowerPC (PPC) chips and this not being a scholarly piece, I'm not going to concern myself or you with researching it; but for context, it was the 3rd generation PPC that was in the PowerBook from yesterday’s article, and the 4th gen one is that in the iBook in front of us now. There was even a 5th generation chip which Apple only included in its desktop range as it simply ran too hot and used to much power to ever put into their laptops. In fact, PPC designs exist even to this very day, although used for only very niche applications. What was great about PPC was that they were powerful for their era, energy efficient, and offered backwards compatibility with the 68000 architecture that the original Macs were based on.

Oh, and it just so happens that the Amiga platform was based on the 68000 also. Not just this, but the Amiga user community continued to develop the Amiga Operating System (originally Workbench, later AmigaOS) and took the source code far beyond that which Commodore left them with when they went bust, and right into the 21st Century. And it didn't stop there - the code that was running on your 1985 Amiga might well be running somewhere in the world today, as the Amiga platform is, an albeit niche, but fully modern platform to rival other community-driven low-energy systems such as the Raspberry-Pi. While I didn't own an Amiga when they were still new, I had plenty of friends who did, and I'm to this day grateful to them for letting me study their machines and the manuals that came with them. I don't know what became of Kieran Denny, but if you're reading this - then you can consider this entire article dedicated to you.

Before we get back on track and back to the business of discussing Apple's best laptops, I just want to add one more aspect of praise on the Amiga platform and its community. The Amiga was always designed as a very expandable machine. What drew me to it particularly when it was new was the fact that Commodore had designed the machine with the ability to add components that would let it run IBM-PC software. While it was a bit of a joke at the time that it was cheaper and faster to buy two separate machines, you couldn't but marvel at the engineering genius that made all this possible. Such design principles mean that if you have an original Amiga you can expand it to being a fully-modern computer today. A company called Vampire makes boards which fit into the Amiga case (in fact, another company makes special modern cases for you to fit your original Amiga's guts into alongside the new board) and this makes it a fully-modern and powerful machine. It's a little like taking a classic Volkswagen Beetle and converting it to an electric Porsche 911. Incredible!

But what's all this got to do with the iBook G4 I hear you ask? Well, if you take your original Amiga, upgrade it to a modern computer - you'll need not just some modern software to run on it, but a modern operating system also. Such an operating system exists in the form of MorphOS, which, since version 3 also runs... on PowerPC-based Apple hardware - and in particular this iBook G4.

In fact, I chose the iBook G4 specifically because it seemed like a good candidate to run MorphOS on. As I was researching this project, and the more I read about MorphOS, the more I saw it to be an alternative platform for everyday productivity computing to the mainstream Operating Systems from Microsoft, Apple and the Linux-based community.

MorphOS has (at least) four great strengths:

The first is that it's a community driven project, and one that is small enough to feel quite tight-knit, unlike the Linux communities which are vast, sprawling and unwieldy. While progress with MorphOS isn't as rapid as the mainstream platforms, you are certainly using an operating system (OS) that is itself used by its creators. It's efficient, but not minimalist; powerful, but not bloated.

This actually brings us to its second strength; it's power-efficient. My 20 year old iBook G4 is not a fast machine by modern standards - in fact I estimate it's about a quarter the power of my 2007 generation Macbook which is itself about 25 times less powerful than Apple's new M2 based machines. But the fact that my 20- year old iBook can browse the modern web on a browser that's been developed by some developers in their spare time is quite something. Let's just stop and pause at the magnitude of this. If you bought an iBook G4 and kept it in a box for 20 years and then opened it today and tried to use the software that it came with - it would be almost totally useless. Even running the software updates to get it to the latest versions that Apple created wouldn't help you being able to browse many modern websites. Even using third-party browsers wouldn't get you much further. This is why there are so many of these machines for sale on eBay as junk, and even more of them are in tiny pieces at the bottom of our oceans, buried in landfill, or burned up in the air we breathe. Except they are not junk, they are perfectly good little computers - even today, in 2022, and these past few months I've been on a mission to prove this point.

So, what of the third strength of MorphOS? Well, it has a software library to die for. The Amiga platform ran from about 1985 to the mid-1990s, but the Amiga community has been writing software to this present day. By contrast, Apple removed support for the classic MacOS from version 10.5 in 2007, and 32-bit apps from version 10.15 in 2019. Microsoft Windows first came out the same year that Commodore released the original Amiga, but good-luck finding a 16-bit Windows app that will run on your 64-bit Windows 11 machine. Even much of the 32-bit Windows back-catalogue is pretty useless today. So, with the Amiga format you've got perhaps the longest anthology of software of any platform, and if you've still got an original machine from the late 1980s, you'll be able to exchange software and data with MorphOS today with relative ease.

Finally, the fourth strength. The boot time is blisteringly fast. After installing MorphOS for the first time, the installer did the customary 'all complete, let's reboot', routine, and while I momentarily glanced away from the screen the laptop had completed a power cycle and rebooted back to the OS. Actually, it was so quick that I was confused at first and thought that the installer must have failed. It then took me a bit of Googling to work out how to 'right' mouse-click in MorphOS and therefore find the reboot option myself – and this time around, glued to the screen, I first saw for myself how quick it is. My daily-driver MacBook takes about a minute to boot, which is quick compared to the Windows workstation that I use for video streaming which faffs about for nearly 4x this long before getting me to the login prompt. MorphOS, by contrast, boots in about 15 seconds. That's faster than any modern phone or tablet I've seen, and aside from some truly ancient machines with their OS on ROM – it's the fastest starting machine I own. Surely, this is how all computers should be?

So, OK - MorphOS runs on a 20- year-old laptop – and has some party tricks, but is it any good? Well, I'm not going to lie to you and pretend this will be as simple as macOS, slick as Windows or as sophisticated as Linux - but in the last few months I'm yet to find a use for a computer that I can't achieve on the iBook running MorphOS. It's not always easy, but it is always fun - and when I've got stuck, the community have been there to help me. Whether you'll be able to replicate my success is really a question of two things; what you use a computer for, and how much patience you have for it sometimes being a little fiddly. I'm guessing on the latter that you've got an above average tolerance, as if you've read this far into my guide to finding the perfect Apple laptop, then you're surely more than just a notch on the geeky-scale. As for the former, well - my confession is that 85% of my computer use is email and web use, with 10% working with spreadsheets, and the remainder writing language - either the human or the machine kind. I haven't found a decent modern spreadsheet yet (Ignition, which seems to be the most well recommended I haven't got to work), and I haven't found a decent modern word processor (the community don't seem particularly interested in this, after all - why wouldn't you just use the Wordsworth programme from the original Amiga-era? and the only one in development looks like the project has been abandoned). As for programming, well - I confess I'm unlikely to be writing software for MorphOS (although never say never), but the system does have VNC, RDP, and remote shell support out of the box, and given that it has Synergy included (an app that lets you 'extend' your computer display by moving your mouse cursor seamlessly from one machine to another next to it), as well as iPad/ iPhone mouse support via it's package manager Grinch, this means I can use my iBook to direct all my computer usage either through a remote connection, second device, or through the command line. So as a dumb-terminal it ticks all the boxes, but what of email and the web?

Well, while the PowerBook G3 was showing signs of struggling with modern email, the iBook G4 with MorphOS has no such limitations. Out of the box is included a package called Iris which is broadly equivalent to Thunderbird. Microsoft Outlook this is not, but once again remember this is a tiny community even compared with the development team behind Thunderbird. Iris is perfectly usable, and I now keep the iBook at home as a device to quickly check email and get back to people that need urgent response - much as I would have used an iPad before (good luck using an original iPad for email if you've made the mistake of performing the one-way software 'updates').

As for the web? Well, it's able to browse 99% of websites - but not without some performance issues. That's not the fault of the MorphOS team, rather more a symptom that the modern web has become enormously bloated and the PPC G4 chip in the iBook is simply not able to keep up. Such as small number of websites cater for low-power devices and older browsers, which is a shame. What's most impressive is that you can actually watch YouTube on the device, and I'd imagine if you had a faster G4 or G5 chip in your machine you'd have no difficulty at all. Of course, if you had a Vampire, either one of their new all-in-one boards, or as an upgrade to a classic Amiga then my performance problems would pale away. As would too the fact that the screen on the iBook is really too small compared to what most of us are used to: it's a 1024x768 panel - or 768p – just under half the vertical resolution of a modern MacBook.

Turning to the screen, my iBook screen feels a little fragile, and somewhere inside there is a loose connection that makes it flash if pressed in the wrong place. Build quality issues I suspect, as Apple hadn't quite perfected the art of laptop screens with the iBook judging from the wobbly screen hinge and rather ugly screw holes in the side of the lid. It's also the last laptop in this series of reviews that has the classic 4:3 aspect ratio rather than the widescreen approach that is more common today. Widescreen laptops became all the rage as DVD drives were fitted as standard and the idea of watching movies on the move really took off. While today, no-one is watching DVDs (and I suspect my younger readers will be off to Wikipedia by now to learn what they were – don’t worry, I’ve hyperlinked the reference for you), the truth is that laptop design is still more biased towards media consumption than productivity. With the exception of big spreadsheets, where wide screens are preferable (and that's why I have ultra-wide screens on my main office workstation), for all other uses the squarer 4:3 ratio is more comfortable and useful to use. I think from reading PC Pro reviews, Huawei has started to make 4:3 ratio laptops again for this very reason - but maybe there are other manufacturers that have also? I know this much though, Apple isn't one of them.

If you do want to watch a DVD on a 4:3 screen to enjoy an authentic turn-of-the-century movie experience, then the iBook will do this for you quite happily with its built-in slot-loading DVD player. Which is handy, as I wasn't able to get Amazon Prime Video to stream via the browser. However, I suspect if I had harassed the community forum hard enough someone would have talked me into how to coax even that into action. As for other multimedia, the iBook has no trouble with music or pictures. Sadly though, no-one has ported Spotify to the platform yet and I think this is a big oversight as I see no reason why it shouldn't work. As for the physical ports, the charger socket is rather irritatingly slightly smaller than the one from my PowerBooks (you see, Apple were already getting into their bad habits as early as 2002), and the connectivity ports on the left include a generous helping of headphones, external monitor, 2x USB, Firewire, ethernet, and a modem. In fact, that is mostly the same combination of ports that will grace Apple laptops for the next 10 years, all the way to the arrival of the Thunderbolt, which, together with the removal of optical drives and ethernet ports, enabled Apple to make their laptops even slimmer again.

Compared to the PowerBook G3, the iBook is a very slim device, but when looking at it next to the latest models one can see how much progress has indeed been made in the last 20 years. A new MacBook is the same thickness as the screen of the iBook. Incredible. But all this thinness has come at a cost, and not just to your wallet; as surely the engineering, design and technology required to make laptops today has resulted in them becoming so expensive also for the planet. The iBook is upgradable and serviceable, and just like the 2007-era MacBook, its battery is removable with just a simple turn of a slot-screw on its base. My own iBook still holds a solid 3-hours charge, which given its age is a small miracle. Good luck though in finding replacement batteries, but well done to Apple engineers of this generation that they recognised that battery life was likely to be the limiting factor for machine longevity and thus users would appreciate a quick and simple replacement. Having the battery replaceable without having to open the case is also a major plus point, as in the situation where mobile use is required for an extended period, one could simply carry multiple batteries and swap them out on the move. Not quite as good as the PowerBook G3 which could take two batteries and therefore operate without interruption in case of a battery swap, but a heck of a lot better than modern machines which require specialists, if not Apple themselves to swap batteries, that is, to the extent it's even possible.

On the subject of expandability and repairability however, the iBook is a bit of a failure. While the hard drive on my machine still seems to have plenty of life left in it, at 60 GB capacity, it's going to be a squeeze to use and explore everything the rich world of Amiga that MorphOS makes possible. This is quite aside from the fact that I would like to have the ability to dual-boot into MacOS, despite not really having any actual purpose for needing to do so. To upgrade the hard drive requires almost fully disassembling the iBook. While on the PowerBook G3 the hard drive could be removed in just a few minutes, it's likely an hour or two of time investment in the iBook, and with so many components to remove - the risk of breaking something in the process is corncerningly high. I'd say this was part of the reason why I've since bought a second iBook - one listed on eBay with a broken hard-drive. While my original is a tidier model, I wouldn't mind a dry-run on something more throwaway in case it transpires to be a bigger job than I had budgeted for. But secretly, the appeal of having two of these machines was very strong also. I can honestly see MorphOS becoming my daily-driver. It'll need a bit more investment in time from me into the community to see what the software archive throws out, and it will also probably require me to have a more powerful MorphOS machine to act as a companion device to the laptop, much how as my Mac Pro is well paired to my favourite Apple laptop (hah, I nearly revealed which one… you’ll still need to wait for the great reveal in the 12th article of this series)! This is an avenue that I think will be rich to explore in the year ahead, and look forward greatly to doing so.

Would I recommend the iBook? It's not entirely Apple's fault that it's not a very useful machine today. But as the last generation machine of a legacy platform, it's no surprise that there is more limited software support for it than for the earlier classic MacOS or later intel-based Macs. I don't think it's a particularly well-engineered machine, yet the design is the inspiration for literally everything that's come after it. And given the existence of MorphOS, it truly has the ability to be a fully useful device still in the 2020s. Which is why I've bought a second. Given what a small community of developers have achieved with MorphOS in their spare time, could you imagine what the folk at Cupertino could produce if they put their minds to keeping some of their old hardware in service? If we could all adopt a slightly more minimalist approach to web-design, discouraged the email giants of Microsoft and Google from cutting off old platforms, and more of us were to dip our toes into a more esoteric niche of the tech world - then perhaps in time the Amiga community could develop into a fourth mainstream computer platform alongside Apple, Microsoft, and the Linux world.

But if it were to become more mainstream, then perhaps it would also lose its charm? For charm and sparkle is exactly what running MorphOS on the iBook simply oozes.

Next article:

Epic read and so much fun to see a trusty PET in the middle. The iBook G4 is close to my first Apple purchase, a PowerBook G4 in sultry aluminium - with over 10 years of use I miss its flexibility in handling anything & never succumbing to a virus or a bsod 🤣