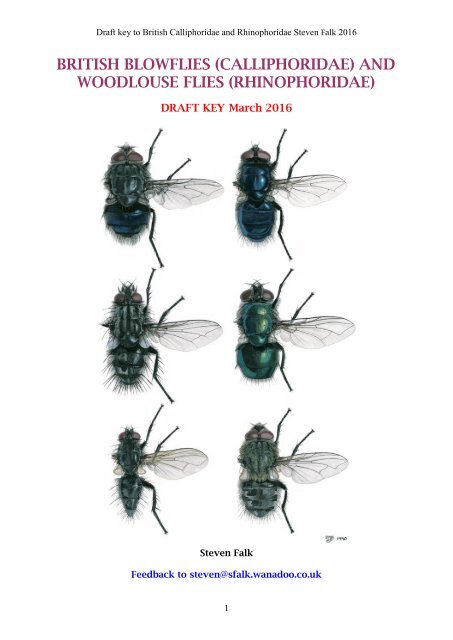

BRITISH BLOWFLIES (CALLIPHORIDAE) AND WOODLOUSE FLIES (RHINOPHORIDAE)

4cmTmdCuA

4cmTmdCuA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

<strong>BRITISH</strong> <strong>BLOW<strong>FLIES</strong></strong> (<strong>CALLIPHORIDAE</strong>) <strong>AND</strong><br />

<strong>WOODLOUSE</strong> <strong>FLIES</strong> (<strong>RHINOPHORIDAE</strong>)<br />

DRAFT KEY March 2016<br />

Steven Falk<br />

Feedback to steven@sfalk.wanadoo.co.uk<br />

1

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

PREFACE<br />

This informal publication attempts to update the resources currently available for<br />

identifying the families Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae. Prior to this, British<br />

dipterists have struggled because unless you have a copy of the Fauna Ent. Scand.<br />

volume for blowflies (Rognes, 1991), you will have been largely reliant on Van<br />

Emden's 1954 RES Handbook, which does not include all the British species (notably<br />

the common Pollenia pediculata), has very outdated nomenclature, and very outdated<br />

classification - with several calliphorids and tachinids placed within the<br />

Rhinophoridae and Eurychaeta palpalis placed in the Sarcophagidae.<br />

As well as updating keys, I have also taken the opportunity to produce new species<br />

accounts which summarise what I know of each species and act as an invitation and<br />

challenge to others to update, correct or clarify what I have written. As a result of my<br />

recent experience of producing an attractive and fairly user-friendly new guide to<br />

British bees, I have tried to replicate that approach here, incorporating lots of photos<br />

and clear, conveniently positioned diagrams. Presentation of identification literature<br />

can have a big impact on the popularity of an insect group and the accuracy of the<br />

records that result. Calliphorids and rhinophorids are fascinating flies, sometimes of<br />

considerable economic and medicinal value and deserve to be well recorded. What is<br />

more, many gaps still remain in our knowledge. We still do not know the biology of<br />

the common Melanomya nana, and biological information for our common Pollenia<br />

species is a mess due to unreliable past identification (with much information being<br />

uncritically assigned to 'P. rudis'). Other species may be increasing or declining, and<br />

we (the entomological and conservation communities) need to keep an eye on this,<br />

particularly in the light of climate change and the impact that this could have on some<br />

of our boreal species in particular e.g. Calliphora uralensis and Bellardia pubicornis.<br />

In addition to this publication, there is a wealth of useful information on Calliphoridae<br />

and Rhinophoridae available freely on the web and this has been listed in the<br />

References & further reading sections further on. This includes my own Flickr site,<br />

which furnishes many more photos of living calliphorids and rhinophorids plus<br />

carefully taken microscope shots designed to show key features. In essence it provides<br />

a virtual field experience plus a virtual museum collection covering almost every<br />

British species.<br />

2

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Classification<br />

The classification within individual families is discussed under those families, but at<br />

the highest level, calliphorids and rhinophorids sit within the the following hierarchy:<br />

Order: Diptera<br />

Suborder: Brachycera<br />

Infraorder: Muscomorpha<br />

Subsection: Calyptratae<br />

Superfamily: Oestroidea<br />

The most closely related familes (i.e. the other families of the superfamily Oestroidea)<br />

are:<br />

Mystacinobiidae - represented by a single species, the New Zealand Bat Fly<br />

Mystacinobia zelandica, a wingless species associated with bats which is<br />

endemic to New Zealand.<br />

Oestridae - bot flies, warble flies and their relatives - winged and strongflying<br />

species with vestigial mouthparts, their larvae developing as internal<br />

parasites of mammals. More closely related to some calliphorids than the<br />

family status would imply and with some life cycles that resemble those of<br />

calliphorid 'screwworms'.<br />

Sarcophagidae - a large and diverse family that includes fleshflies (with<br />

larvae that develop variously in carrion, excrement, living invertebrate hosts<br />

etc.) plus the satellite flies that are cleptoparasites and parasitoids of bees and<br />

wasps.<br />

Tachinidae - a huge and diverse family of parasitic flies, some closely<br />

resembling calliphorids. The larvae developing internally within other insect<br />

larvae e.g. caterpillars, or even adult bugs and beetles, depending on the<br />

species.<br />

However, it should be noted that this is a disputed classification because the<br />

Calliphoridae does not appear to be monophyletic, and its evolutionary relationship is<br />

entwined with some of the above families, notably Oestridae (Rognes, 1997).<br />

Collecting and recording<br />

Collecting calliphorids and rhinophorids<br />

There are essentially three approaches to recording flies such as calliphorids and<br />

rhinophords:<br />

Active collecting/recording - which can involve netting or visual<br />

identification in the field, the latter being possible for many species once<br />

experience has been gained.<br />

Passive collecting/trapping - using devices such as water traps (pan traps),<br />

malaise traps and bait traps to attract and automatically catch adults.<br />

Rearing - by taking items potentially containinng larval stages e.g. hosts such<br />

as snails, earthworms and woodlice, or carrion, and seeing what species<br />

3

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

emerge. This technique can also be extended to get species to oviposit on bait<br />

traps or deliberately supplied hosts.<br />

All three can be highly active and have attributes. Active collecting can be 'freeform',<br />

allowing you to interrogate all parts of a site and observe adult behaviour and<br />

distribution within a site. Trapping can provide hard numerical data and is a more<br />

standardised and replicable approach that can also save time. Rearing can elucidate<br />

larval requirements and relationships with host taxa.<br />

The best type of net to use is a long-handled insect net with a 40cm diameter net<br />

frame bearing a white, nylon net bag. The best handles are fishing landing net poles<br />

which can be extended from 1.5 metres to perhaps 2.5-3 metres depending on the<br />

model. This type of net arrangement can be used both to spot-capture an individual fly<br />

or to sweep flowers, foliage and herbage to obtain specimens. Because many<br />

blowflies are skittish and fast-flying, a long handled net that keeps your body further<br />

away can be a lot more productive than a short-handled kite net, though kite nets can<br />

be useful in more confined settings, gardens etc.<br />

Sweeping with a long-handled insect net<br />

Because many blowflies are in regular contact with carrion or excrement, it is not<br />

advisable to pooter them up, unless you use a mechanical pooter. Netted flies are best<br />

transferred to glass tubes or to a killing jar. I generally grab them with my fingers and<br />

put them in a killing jar, because they can damage their wings or become damp (and<br />

discoloured) if kept in a small glass tube for any amount of time. But remember that<br />

your hand is then a potential health hazard, so keep it away from your face and any<br />

food or drink you have. If you have some water and antiseptic wipes, it is easy to<br />

clean your hands in the field following handling of blowflies.<br />

4

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

The best killing agent is ethyl acetate but you can also employ the old-fashioned<br />

technique of using crushed Cherry-laurel leaves in a killing jar, or freezing your catch<br />

overnight.<br />

Where and when to look<br />

Some calliphorid and rhinophorid species are fairly habitat specific or geographically<br />

restricted, so you need to be in the right place before you can even contemplate<br />

searching for them e.g. submontane parts of the Scottish Highlands for species such as<br />

Calliphora stelviana or a coastal areas of NW Scotland for C. uralensis. But the vast<br />

majority of species are much more widespread and catholic in their habitat choice and<br />

can be encountered in many places.<br />

Many calliphorids and rhinophorids like to sunbathe on foliage in sheltered spots, so<br />

scrutinising bramble foliage and the foliage of sunny woodland rides and hedges can<br />

be rewarding. Sunlit walls, tree trunks and rocks can be good too. Many species like<br />

to visit flowers, and umbellifers such as Hogweed, Angelica, Wild Carrot and Wild<br />

Parsnip can be particularly good, also composites such as Fleabane, ragworts, thistles,<br />

mayweeds and Oxeye Daisy. Autumn-flowering Ivy can be exceptionally good for<br />

Calliphora and Pollenia species where it is in warm sheltered spots. In spring,<br />

blossoming willows, Blackthorn, cherries, plums, apples and hawthorns are much<br />

used.<br />

Ivy flowers in sheltered and sunny locations are one of the best places to see concentrations of<br />

blowflies representing a variety of species<br />

Adult females usually require a proteinaceous meal to mature their eggs, and will visit<br />

fresh excrement and carrion specifically for this purpose. Carrion is also where you<br />

will find egg-laying females of Calliphora, Cynomya, Lucilia and Protophormia<br />

species.<br />

Wetlands are the preferred habitat of species such as Lucilia bufonivora, L. silvarum,<br />

Angioneura species and several Pollenia species. Calliphora subalpina, Lucilia<br />

ampullacea and Paykullia maculata prefer woodland and denser scrub. Synanthropic<br />

species that can be regularly found indoors include Calliphora vicina, Lucilia caesar<br />

and Melanophora roralis.<br />

5

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

The best period to find and record blowflies is between early spring (when the first<br />

blossoms appear) and autumn (when the Ivy is flowering). But blowflies can still be<br />

evident in winter, especially hibernating clusterflies or the occasional winter-active<br />

Calliphora vicina.<br />

Remember that you can records blowflies in the field in other ways too. A toad<br />

parasitised by Lucilia bufonivora has fairly distinctive symptons. If you are an<br />

ornthologist licenced to study nesting birds, you may spot the maggots of<br />

Protocalliphora azurea attached to a nestling. But do not record it on the basis of<br />

pupae in a nest, because these could just as easily belong to a Calliphora species that<br />

has used a dead nestling.<br />

Pinning specimens<br />

There are several ways of doing this. The one I prefer is to side pin them onto<br />

Plastazote using a single micropin (which come in assorted sizes) through the side of<br />

the thorax. In this orientation it is easier to pull out the male genitalia, female<br />

ovipositor and mouthparts and ensure that they dry in an exposed position to allow<br />

easy checking. When the specimens are dry and 'set' (usually within a week), they can<br />

be staged. To do this, you take a short strip of Plastazote (perhaps 10mm x 3mm x<br />

3mm depending on the size of the specimen) and place a long, headed pin (ideally<br />

40mm) though one end and place your pinned specimen at the other end. A locality<br />

label can then be placed on the long pin. This approach is better than placing the main<br />

long pin directly through a specimen because once a specimen is brittle, any flex in<br />

the pin could damage it. It is also difficult to use long pins for tiny species such as<br />

Angioneura and Melanomya species or the smaller rhinophorids.<br />

A staged Lucilia male (left). Part of the authors calliphorid collection, which is kept in storeboxes<br />

(right)<br />

A variation upon the above theme is to pin specimen butterfly-style by placing the<br />

micropin through the top of the thorax to one side of the midline so that the bristles on<br />

at least one side of the thorax remain undamaged. The wings and legs can then be<br />

made to dry in the desired fashion using further micropins to hold them in place until<br />

they are set. This can create a very neat and nice-looking specimen, though it is<br />

almost impossible to get the genitalia to dry in an exposed position using this<br />

technique. The specimen is then staged as above, though a longer strip of Plastazote<br />

may be required.<br />

6

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Abroad, long pins are often used directly and inserted through the top of the thorax. If<br />

this approach is chosen, it is important that the storage container is lined with soft<br />

Plastazote rather than cork, because the pin is more likely to flex with the latter.<br />

Storing specimens<br />

Perhaps because of their size and odour, blowfly specimens are quite vulnerable to<br />

attack from pests such as Anthrenus carpet beetles (museum beetles), booklice and<br />

dust mites. It is therefore important that specimens are kept in tight-fitting containers.<br />

Wooden cabinets with good quality drawers or tight-fitting entomological storeboxes<br />

are best. It is important that these are kept away from direct contact with the floor<br />

(especially woollen carpets) and walls, because this will make it much more difficult<br />

for pests to gain access. Specimens should also be kept in fairly warm and dry<br />

locations, because damp will encourage mould, and this can quickly ruin a specimen.<br />

Body parts and glossary<br />

The body is divided into three main sections, the head, thorax and abdomen. The<br />

thorax gives rise to a pair of wings, a pair of halteres, and three pairs of legs.<br />

Head<br />

This has a pair of large compound eyes on each side which are usually much more<br />

widely separated on top in females than males. They are separated at the top by the<br />

frons, which extends from the rear of the ocellar triangle (containing three small<br />

ocelli) to the lunule immediately above the antennal insertions. The frons comprises a<br />

pair of parafrontalia (orbits) immediately beside the eyes (usually silver-dusted) and a<br />

darker interfrontalia (frontal vitta) inbetween. The width of the frons and relative<br />

width of the parafrontalia and interfrontalia can be important in identification. Frontal<br />

bristles line the edges of the interfrontalia and several pairs of orbital bristles can be<br />

present along the parafrontalia. A pair of ocellar bristles arise from the ocellar triangle<br />

and an inner and outer vertical bristle is present close to the inner hind corner of each<br />

compound eye.<br />

The back of the head is called the occiput and has a row of postocular bristles at the<br />

top and sides running parallel to the hind margin of the eye. The occiput merges into<br />

the genae (cheeks) below each compound eye, which contain a densely haired area<br />

called the genal (or occipital) dilation. The depth and colour of the genae can be<br />

important in identification. The sides of the face between the eyes and the facial<br />

ridges are called the parafacialia and are often heavily dusted. They can be bare, hairy<br />

or bristly. The oral opening at the bottom of the face has a pair of strong bristles<br />

called the vibrissae on either side at the front.<br />

A pair of antennae arise from the top of the face immediately below the crescentshaped<br />

lunule. Three major antennal segments are present, segment 1 (often termed<br />

the scape), segment 2 (often called the pedicel) and the long segment 3 (often called<br />

the first flagellomere). I have stuck to the most user-friendly terms here. The third<br />

segment bears a long arista which may be plumose (i.e. bearing long ray hairs),<br />

7

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Main body parts of a blowfly<br />

pubescent (bearing short hairs) or virtually bear. The mouthparts bare a pair of palpi,<br />

the colour of which can be important for identification.<br />

Thorax<br />

This is a complex part of the body, but it is mostly the upper side that is used for<br />

identification, especially the arrangement of bristles here. The mesonotum dominates<br />

the top of the thorax and has a ridge (mesonotal suture) running across the middle that<br />

divides it into a presutural and postsutural area. Several bristle rows run down the<br />

mesonotum. The central two rows are called the acrostichals. A row of dorsocentrals<br />

is located on each side of the acrostichals and a row of intra-alars towards the sides of<br />

the mesonotum. Several supra-alars are present immediately above the wing bases,<br />

the front of which is called the prelalar. A swollen humerus (also known as a humeral<br />

callus) occurs at each front corner of the thorax and has three large humeral bristles<br />

and often several subsidiary anterior humeral bristles in front of these. On each side of<br />

8

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

the mesonotal suture is another lobe called the notopleuron with a pair of large<br />

notopleural bristles. At each hind corner of the mesonotum is a narrow swollen lobe<br />

called the postalar callus which bears a pair of strong postalar bristles. The<br />

semicircular section of the thorax immediately behind the mesonotum is called the<br />

scutellum and has a pair of apical bristles and a variable number of strong marginal<br />

bristles around the edges, the number of which can be important in identification. The<br />

relative length of these can also be important in identification.<br />

Abdomen<br />

This is clearly segmented with tergites forming the top and wrapping themselves<br />

around the sides. The ventral sternites are located down the middle of the underside<br />

between the edges of those tergites. It is important be be aware that the first apparent<br />

tergite is actually a pair of fused tergites and is called tergite 1+2. This means that the<br />

apparent second, third and fourth tergites are actually tergites 3, 4 and 5. I have stuck<br />

with convention here to avoid conflict and confusion with other literature. Tergite 6<br />

and sternite 6 onwards represents the genitalia. In the male this takes the form of a<br />

capsule that is retracted into the end of the abdomen and only unfolded during<br />

copulation. It contains a pair of cerci on either side of the anal opening and lateral<br />

claspers called the surstyli on either side of the cerci, the shape of both of which can<br />

be very important in species identification (see the diagrams for genera such as<br />

Bellardia, Calliphora and Lucilia). A single aedeagus is present (the equivalent of a<br />

penis), the shape of which is also useful for critical identification and taxonomy,<br />

though it has not been used in this work). It is important to ensure that the male<br />

genitalia dries in an exposed position when pinning and setting a male.<br />

The female ovipositor takes the forms of a telescopic tube. It can be important in<br />

critical identifications and taxononic work but is only used for the separation of<br />

Lucilia caesar from L. illustris here. It is most easily examined in material stored in<br />

preservative.<br />

Wings<br />

The wings of calliphorids and rhinophorids follow a standard oestroid pattern, with<br />

the final section of vein M (the section after cross vein dm-cu tending to be sharply<br />

upturned towards the wing tip. Exceptions occur in assorted rhinophords (and some<br />

tachinids) where vein M meets vein R4+5 before the wing tip to create a petiolate or<br />

stalked condition (see wing diagrams of species such as Melanophoria and Stevenenia<br />

later on). Some foreign rhinophorids (plus a number of British tachinids) have vein M<br />

straight which can invite confusion with flies of the family Muscidae and<br />

Anthomyiidae or even acalypterate flies). Various features of identification value can<br />

be present on the wings, including wing vein details, certain hairs, bristles and spines,<br />

plus patterns on the wing membrane. The shape of the lower calypter and its colour<br />

and presence of any hairs on its upper surface can also be valuable.<br />

Legs<br />

These comprise the usual components of fly legs i.e. a coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia<br />

and 5 tarsal segments terminating in a pair of claws. Features of value include the<br />

presence of certain bristles, leg coloration and the length and relative proportions of<br />

individual segments. Bristle orientation is named following a strict convention. If a<br />

leg was theoretically stetched to the side of the body, a dorsal bristle would face up, a<br />

ventral one down, an anterior one to the front and a posterior one to the rear. A<br />

9

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

'posteroventral' bristle (e.g. those on the front tibiae of Bellardia pandia) is one that<br />

falls between a ventral and posterior orientation, and this rule can also be applied to<br />

posterodorsal, anterodorsal or anteroventral bristles.<br />

Main features of a typical oestroid fly wing<br />

Identifying oestroid families<br />

1 Mouthparts vestigial, any oral opening less than one-tenth the head<br />

width.…………………………………………………........................….Oestridae<br />

- Mouthparts obvious and oral opening at least one-fifth the head width............…..2<br />

2 Hypopleural bristles either absent or with hairs/weak bristles immediately below<br />

the hind spiracle.......................................Muscoidea (Anthomyiidae, Fanniidae,<br />

Muscidae & Scathophagidae)<br />

- Hypopleural bristles strong and arranged as a neat row (Fig 1)...….........…...……3<br />

3 Subscutellum (a convex pad below the scutellum) well formed (Fig<br />

2)..........................................................................Tachinidae (except Lithophasia)<br />

- Subscutellum not well differentiated…….…….............………….……………….4<br />

4 Inner edge of lower calypter diverging away from the sides of the scutellum when<br />

viewed from above (Fig 4)………......................................………...…….....….....5<br />

- Lower calypter with inner edge hugging the sides of the scutellum when viewed<br />

from above (Fig 3)..………………....................................…………..…….......….9<br />

5 Upper side of stem vein hairy along hind margin (p18, Fig 1). Species either<br />

metallic or with a strongly protruding lower face (p18, Fig, 2). Cell R4+5 always<br />

open........................................................................................Calliphoridae in part<br />

- Upper side of stem vein bare. Species never metallic. Lower face never protruding<br />

except for Rhinophora lepida which has R4+5 stalked...........................................6<br />

6 Cell R4+5 never open, vein R4+5 either stalked or meeting vein M at the wing<br />

margin (p 73, Figs 2-4).............................................................................................7<br />

- Cell R4+5 at least narrowly open (p 18, Figs 6-8)...................................................8<br />

7 A small, stout, shiny black species without any bristles on the tergites. R4+5 longstalked.<br />

Wings clear....................................Litophasia hyalinipennis (Tachinidae)<br />

10

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

- Slimmer species with obvious bristles on the tergites, at least marginals on tergites<br />

3-5. R4+5 either short or long-stalked. Wings clouded or marked in some<br />

species...............................................................................................Rhinophoridae<br />

8 Scutellum yellowish apically. Tibiae, genae and at least tip of antennal segment 2<br />

reddish.............................................................................some Tricogena rubricosa<br />

- Scutellum never yellowish apically. Tibiae, genae and antennae<br />

black.......................................................................................Calliphoridae in part<br />

9 Thorax with wavy golden or straw-coloured hairs somewhere on its surface, often<br />

rubbed off the dorsal surface but in this instance visible somewhere on the<br />

pleurae……...........................................................…..….Pollenia (Calliphoridae)<br />

- No such hairs present anywhere on the thorax…….……………….................…..8<br />

10 Proepisternal depression setulose (Fig 5). Prosternum (the small chitinous plate<br />

between the base of the front coxae) hairy in most species (like p19, Fig 1). Vein<br />

M without a fold or appendix at the point of its upturn, the bend obtuse in some<br />

species and the upturned section either curved or straight (Figs 6 & 7). Some<br />

species metallic blue or green, at least on tergites.................Calliphoridae in part<br />

- Proepisternal depression bare. Prosternum usually bare. Vein M sharply upturned<br />

and usually with a fold or small appendix at the bend, the uptuned section nearly<br />

always distinctly curved at the bottom (Fig 8). Never metallic...….Sarcophagidae<br />

The flies most likely to be confused with blowflies in the field are other metallicgreen<br />

or metallic-blue members of the families Muscidae and Tachinidae. Our two<br />

Neomyia species (Muscidae) are strikingly similar to Lucilia greenbottles and very<br />

common in pastoral habitats. Look out for the shiny green frons and the straighter<br />

upturned section of vein M. Another common muscid, the metallic-green<br />

Eudasyphora cyanella is somewhat less convincing due to the stripes on the<br />

mesonotum and the gently curved vein M. Our other Eudasyphora, E. cyanicolor is<br />

deep metallic blue and resembles a Melinda species in the field but has the same<br />

gently curved vein M as E. cyanella and a characteristic stripe of white dusting at the<br />

front of the mesonotum. The metallic-green tachinid Gymnocheta viridis is much<br />

more bristly than a Lucilia, and a rather different shape, with a smaller head and<br />

longer legs. It can be common sunbathing on tree trunks in spring.<br />

11

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Greenbottle look-alikes<br />

The muscid Neomyia viridescens male (left and female (right) look very Lucilia-like but have a<br />

metallic-green frons that is especially obvious in the female.<br />

The muscid Eudasyphora cyanella (left) has stripes at the front of the thorax unlike any Lucilia and<br />

vein M is more gently curved. The tachinid Gymnocheta viridis (right) is an altogether bristlier fly with<br />

longer legs than a Lucilia, and vein M more strongly curved.<br />

Bluebottle look-alikes<br />

The muscid Eudayphora cyanicolor male (left) and female (right) resembles a Melinda species but has<br />

a whitish median dust stripe at the front of the thorax and vein M gently curved.<br />

12

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

<strong>CALLIPHORIDAE</strong> – <strong>BLOW<strong>FLIES</strong></strong><br />

An extremely diverse family of flies that in Britain includes familiar bluebottles,<br />

greenbottles and cluster-flies plus some very different forms such as the rhinophoridlike<br />

genera Angioneura, Eggisops and Melanomya and the Sarcophaga-like<br />

Eurychaeta. Appearances can become even more striking abroad and it worth<br />

comparing our British fauna with that found in Australia, where Calliphora<br />

'bluebottles' become non-metallic 'goldbottles' and some stunning metallic and<br />

patterned species can be found (see the Brisbane Insects website cited in the<br />

References).<br />

In fact, there is general agreement that current concept of Calliphoridae is not a<br />

natural grouping with a single (monophyletic) origin, but is polyphyletic with several<br />

potentially good families e.g. Polleniidae, Helicoboscidae and Bengaliidae within a<br />

classification entwined with what remains of a monophyletic Calliphoridae plus the<br />

bot fly and warble fly family, Oestridae. Oestrids are are essentially specilaised<br />

calliphorids adapted to a parasitic lifestyle (Knut Rognes, 1997 and Systema<br />

Dipterorum). Concensus is currently lacking on how to resolve this conundrum. One<br />

option would be to be place the current concept of Calliphoridae within the Oestridae<br />

(an older family name), but this would have major nomenclatural implications for<br />

many economically and medically important species.<br />

In the current polyphyletic arrangement recognised by the Global Biodiversity<br />

Information Facility (GBIF) the family contains nearly 1900 species in almost 200<br />

genera with a distribtion that stretches from the arctic to various subantarctic islands.<br />

Diversity is highest in the Old World and a significant proportion of the New World<br />

fauna comprises introduced Old World species of genera such as Chrysomya and<br />

Pollenia. The British and Irish list currently comprises 38 species in 14 genera and 7<br />

subfamilies (see Checklist at end). There has been considerable instability in British<br />

calliphorid nomenclature historically and this is untangled in the Name Change<br />

Navigator at the end.<br />

Calliphoridae biology<br />

Within the British fauna, life cycles fall mostly into one of three categories:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Carrion feeders and facultative myiasis agents: Calliphora, Cynomya,<br />

Lucilia and Protophormia. These typically use carrion but will exploit wounds<br />

in living mammals (a phenomenon known as myiasis). Some of these species<br />

are a serious source of sheep fly-strike (myiasis of sheep). Others are<br />

important species in forensic entomology and medicinal maggot therapy.<br />

Snail predators and parasites: Angioneura, Eggisops, Eurychaeta, Melinda<br />

and possibly Melanomyia<br />

Earthworm predators and parasites: Bellardia and Pollenia<br />

In addition to these, Lucilia bufonivora is an obligate internal parasite of amphibians<br />

(typically toads), Protocalliphora azurea has larvae that suck blood from bird<br />

nestlings and Stomorhina lunata has larvae that develop in locust egg pods. Most<br />

13

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

species are oviparous but Bellardia, Eggisops and Eurychaeta are larviparous<br />

(viviparous). Much more information on the biology of British blowflies is provided<br />

by Erzinçlioglu (1996).<br />

Many extra life cycles occur in foreign species, including species associated with ant<br />

nests and termite nests. Screwworms are the blowflies that cause subcutaneous<br />

myiasis of mammals including humans in warmer climes and use living rather than<br />

necrotic tissue. They include the Old World Screwworm Chrysomya bezziana in<br />

tropical and subtropical parts of Asia and Africa and the New World 'Primary'<br />

Screwworm Cochliomyia hominivorax of the New World tropics.<br />

Erzinçlioglu (1989) discusses the origins of vertebrate parasitism (myiasis) in<br />

blowflies, arguing that it arose from saprophagous origins but has been much<br />

influenced by stock-farming and animal husbandry, with calliphorid myiasis being<br />

much rarer in truly wild mammal populations, but relatively frequent in domesticated<br />

stock and zoo animals, and involving facultatively parasitic calliphorid species that<br />

rarely attempt myiasis in more natural ecosystems.<br />

Sheep fly-strike<br />

Sheep fly-strike (also known as sheep-strike or blowfly strike) is the infection of live<br />

sheep by blowfly maggots. It can take place in an existing wound or can result from<br />

larvae burrowing into non-infected skin, especially where wool is badly soiled and<br />

contains skin flakes. Considerable loss of condition and even death can result and<br />

financial loss to sheep farmers can be considerable, so sheep fly-strike has been<br />

subject to considerable research. The main blowfly species involved in Britain are (in<br />

order of importance) Lucilia sericata, L. caesar and Calliphora vomitoria. Treatment<br />

is through the use of registered chemicals such as synthetic pyrethroids. As well as<br />

sheep, blowflies can occasionally infect other stock species plus pet species.<br />

Lucilia species ovipositing on wool (Photo: Chris Raper)<br />

14

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Blowflies and forensic entomology<br />

Human corpses can start to attract blowflies within hours of death. The process of<br />

maggot-assisted composition that then ensues can act as a biological clock, providing<br />

vital clues as to when a death occurred (the postmortem interval) plus other<br />

information that can assist an investigation. Analysis is not straightforward as<br />

variables such as temperature, weather and location all need to be accounted for.<br />

There is a huge amount of literature on the forensic use of blowflies.<br />

Greenbottles, bluebottles and muscids on a fresh Wild Boar corpse (Photo: Olga Retka)<br />

Maggot therapy using blowflies<br />

The majority of blowflies that cause myiasis in mammals use necrotic rather than<br />

living tissue and it had been common practice in some cultures such as Australian<br />

Aborigines and Mayan Indians to dress septic wounds with such maggots to prevent<br />

the spread of gangrene. The maggots not only eat and remove the necrotic tissue but<br />

also produce anti-bacterial secretions that can reduce or eliminate the infection. In<br />

World War 1, maggot therapy was used in a deliberate fashion as a quick and costeffective<br />

technique for treating infected wounds. But maggot therapy remains<br />

important today (including within Britain where it is available through the NHS),<br />

especially as some antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria are difficult or expensive to<br />

treat in any other way. Maggot therapy is especially useful for pressure ulcers,<br />

diabetes-related foot ulcers and infected burns. The main blowfly species used are<br />

Lucilia sericata and Protophormia terraenovae. The maggots are disinfected before<br />

use and are usually kept in the wound using a bag that prevents escape of the maggots<br />

whilst still allowing oxygen to reach them. Treatment typically lasts a few days, is<br />

relatively cheap and can often be undertaken at home rather than in a hospital.<br />

15

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Calliphoridae identification<br />

The keys presented here only cover the British species. However, it is useful to be<br />

aware of species that occur in Europe or synanthropic species in other parts of the<br />

world. There is a good chance that some of these species will arrive and maybe even<br />

establish in Britain. A number of widespread North American blowflies appear to be<br />

European imports, and there is no reason why some of theirs (e.g. Calliphora livida)<br />

might not end up here establishing populations around airports. Maybe they have<br />

arrived already. How often are the blowfly populations of ports and airports screened?<br />

Useful foreign accounts include:<br />

Fennoscandia and Denmark: Rognes (1991)<br />

Netherlands, Belgium and Germany: Huijbregts (2002) - a useful list but no<br />

keys<br />

Norway: Rognes online account<br />

European species of forensic importance: Szpila online (undated)<br />

Middle East: Akbarzadeh et. al. (2015)<br />

North America generally: Whitworth (2006)<br />

Eastern Canada specifically: Marshall et.al. (2011)<br />

Key to calliphorid genera<br />

1 Stem vein with long hairs above along rear edge (hairs pale in Stomorhina so<br />

easily overlooked) (Fig 1). Lower calypters with inner edge diverging away from<br />

the sides of the scutellum (Figs 3 & 4)….................................................................2<br />

- Stem vein bare above. Lower calypters with inner edge usually hugging the sides<br />

of the scutellum (Fig 5)……...........................................………………...………..5<br />

2 A non-metallic species with lower face strongly produced (Fig 2) and mesonotum<br />

strongly striped with grey and black. Male second and third tergites with large<br />

orange patches laterally...………..............……………………..Stomorhina lunata<br />

- Metallic blue or green species without a strongly produced lower face.<br />

Mesonotum not dusted as above….......................…………..……………….……3<br />

3 Acrostichals barely differentiated from the hairs of the mesonotum. Calypters<br />

smoky grey-brown with darker brown rims. Body dark metallic blue in both sexes<br />

without any obvious dusting..……………………….…Protophormia terraenovae<br />

- Acrostichals well differentiated. Calypters whitish or yellowish-grey, usually<br />

without much darker rims (though the hair fringe these give rise to may be<br />

darker). Mesonotum usually with obvious pale dusting, at least at the front when<br />

viewed from behind, the body either dark metallic blue or with green-turquoise<br />

reflections…………………………………………....…………………………….4<br />

4 Inner edge of lower calypters diverging strongly from scutellum when viewed<br />

from above (Fig 3). Acrostichals longer, mostly equal to the length of the<br />

scutellum. Antennae, basicostae and anterior thoracic spiracles blackish or<br />

brownish. Male eyes separated by about 1.5 times the width of a third antennal<br />

segment…….….............................................................…..Protocalliphora azurea<br />

- Inner edge of lower calypter not diverging so strongly from the scutellum when<br />

viewed from above (Fig 4). Acrostichals shorter, mostly about half the length of<br />

the scutellum. Basicostae and anterior thoracic spiracles pale brown or orange, the<br />

16

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

antennae also partly reddish. Male eyes separated by about half the width of a<br />

third antennal segment.……………………........….…………..….Phormia regina<br />

5 Final section of vein M with a conspicuous sharp bend of about 70-110 degrees<br />

within the basal third of its length, the final section either straight, or curved so as<br />

to create a concavity within cell R4+5 (Figs 6 & 7). Species robustly built, some<br />

with tergites metallic green, blue or bronze….........................................................6<br />

- Final section of vein M with a more gently curved or obtuse bend of about 130<br />

degrees, which is near the middle (Fig 8). Slim, non-metallic, small or very small<br />

species.…......................................................................................................….....13<br />

6 Tergites obviously metallic green or blue...……...............………...……………...7<br />

- Tergites not obviously metallic but always strongly patterned by dusting............11<br />

7 Both thorax and abdomen strongly metallic green, bronze or turquoise with any<br />

dusting weak and barely obscuring the underlying coloration. Suprasaquamal<br />

ridge with a sclerite bearing a tuft of setae (Fig 9, best seen when wings are<br />

open)…................……………………………….........……………………..Lucilia<br />

- At least thorax with some obvious dusting and never strongly reflective. Tergites<br />

either undusted (Cynomya) or with shifting areas of dusting. Suprasquamal ridge<br />

without such a tuft of setae..............................................................................….....8<br />

8 Lower calypters bare above. Depth of genae no more than one-third the height of<br />

an eye (Fig 10). Face, frons, genae and antennae (excluding any dusting) always<br />

dark. Tergites metallic blue…………............…..............…………..……..Melinda<br />

- Lower calypters with long hairs on upper surface (Figs 5 & 16). Depth of genae<br />

usually at least two-fifths the height of an eye (Figs 11 & 12). Antennae, face,<br />

frons and genae often extensively yellow, orange or reddish. Tergites metallic<br />

blue or green............................................................................................….....……9<br />

9 Only one pair of postsutural acrostichals, the prescutellar pair (Fig 13). Tergites<br />

entirely undusted and brightly shining blue or turquoise. Face, genae and much of<br />

frons yellow or orange. Male genitalia large with long curved surstyli (Fig 15).<br />

Female with hind margin of tergite 4 and entire surface of tergite 5 bearing very<br />

strong bristles.…………………………….…..............……..Cynomya mortuorum<br />

- Three pairs of postsutural acrostichals (Fig 14). Tergites in most species with<br />

obvious dusting (in Calliphora stelviana best seen when viewing abdomen from<br />

behind)…………………………….............................................................….…..10<br />

10 Tergites metallic-blue. Parafacialia only hairy on upper part (hairs not extending<br />

much lower than a level equivalent to the aristal insertion point, Fig 11). Lower<br />

calypters often hairy over most of their upper surface (Fig 5). Third antennal<br />

segment 3-5 times as long as wide and often extensively red or orange. Face, frons<br />

and genae often extensively yellow, orange or reddish…..................…..Calliphora<br />

- Tergites metallic-green, turquoise or bronze. Parafacialia hairy over much of<br />

length (hairs extending down to a level equivalent to the mid point of the third<br />

antennal segment or beyond (Fig 12). Lower calypters only hairy over about onethird<br />

of their upper surface, broadly bare around their margins (Fig 16). Third<br />

antennal segment 2-2.5 times as long as wide, at most red at extreme base. Face,<br />

frons and genae entirely or mainly dark.......................Bellardia (ex B. pubicornis)<br />

11 Thorax with wavy golden or straw-coloured hairs somewhere on its surface, often<br />

rubbed off the dorsal surface but in this instance visible somewhere on the<br />

sides.....…………..……….........................................................…...……...Pollenia<br />

- Thorax never with such hairs……………………………...........………………..12<br />

17

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

12 Lower part of parafacialia with some very long and strong bristles (Fig 17).<br />

Mesonotum and tergites with exceptionally long and strong bristles. Costal bristle<br />

barely differentiated. Closely resembling a Sarcophaga<br />

species….............................................................................…..Eurychaeta palpalis<br />

- Lower part of parafacialia without long and strong bristles. Bristles of mesonotum<br />

and tergites not exceptionally long or strong. Costal bristle much longer than cross<br />

vein r-m…......................................................................……..Bellardia pubicornis<br />

13 Two pairs of strong scutellar marginal bristles in addition to the apicals (Fig 18).<br />

Propleural depression and lunula setulose. Notopleuron with fine hairs in addition<br />

to the two bristles. Larger (wing length 4.5-6mm)………...…..Eggisops pecchiolii<br />

- Only one pair of scutellar marginals in addition to the apicals, these being much<br />

longer than the apicals (Fig 19). Propleural depression and lunula without setae.<br />

Notopleuron bare apart from the two bristles. Smaller species (wing length up to<br />

4mm)……...........................................………………………………..............….14<br />

14 Arista plumose. Parafacialia finely setulose. Prealar bristle much stronger than the<br />

hind notopleural. Halteres dark…….........................……………Melanomya nana<br />

- Arista pubescent. Parafacialia bare. Prealar no longer than the hind notopleural.<br />

Halteres yellow……................……..................................……………Angioneura<br />

18

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Angioneura – least blowflies<br />

Small, non-metallic, somewhat muscid-like blowflies with an obtuse bend about half<br />

way along vein M (as in Melanomya and Eggisops). The aristae are pubescent rather<br />

than plumose and the parafacialia bare. The scutellum has a pair of rather short<br />

apicals flanked by a pair of much longer marginals. This is a holarctic genus with<br />

perhaps 8 species worldwide depending on how the limits of the genus are defined.<br />

Some are known to be oviparous snail parasitoids. Represented in Britain by two very<br />

rare species, with a third species, A. fimbriata, known from the near continent.<br />

Key to species<br />

- Prosternum (the narrow chitinous plate between the base of the front coxae)<br />

usually setulose (Fig 1). Lower calypters viewed from above broadening<br />

posteriorly with their inner edges hugging the sides of the scutellum (Fig 2).<br />

Parafacialia with a few setulae in upper half. Tergites completely dusted. Anal<br />

vein only extending about half way to the wing margin. Male eyes separated by<br />

about the width of a third antennal segment (Fig 4). A grey species with<br />

completely dusted tergites................................................................……..….acerba<br />

- Prosternum bare. Lower calypters viewed from above with their inner edge<br />

diverging away from the scutellum (Fig 3). Parafacialia bare. Anal vein almost<br />

extending to the wing margin. Male frons about one-quarter the width of the head<br />

(Fig 5). A darker species with tergites mostly (male) or entirely (female)<br />

blackish….............................................................................................cyrtoneurina<br />

Angioneura acerba (Meigen, 1838)<br />

Pale Least Blowfly<br />

Description & similar species WL 3-3.5mm. A tiny greyish species that could easily<br />

be overlooked as a small anthomyiid or muscid until the upturned vein M is spotted.<br />

The mesonotum and tergites have inconspicuous shifting markings with the humeri a<br />

little paler. The lower calypters broaden posteriorly, their inner edge hugging the side<br />

of the scutellum. The male frons is about the width of a third antennal segment. That<br />

of the female is about one-third the width of the head.<br />

Variation The prosternum can occasionally lack bristles.<br />

Flight season May to October in Fennoscandia, with British records for June, July<br />

and August.<br />

19

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Habitat & biology Clearly associated with wetlands, perhaps especially spring- or<br />

seepage-fed marsh with shallow calcareous water. Presumed to be a parasitoid of<br />

snails.<br />

Status & distribution Rare, with records confined to Oxford, Oxfordshire (1966),<br />

Kennet Floodplain, Berkshire (2003), Godmanchester, Cambridgeshire (2007) and<br />

Stoney Moors, New Forest (2008). Quite numerous at the last-mentioned site.<br />

Male Angioneura acerba (left, Photo: Hedy Van Pratternburg) and pinned female (right). Notice the<br />

narrow frons of the male.<br />

Angioneura cyrtoneurina (Zetterstedt, 1859)<br />

Dark Least Blowfly<br />

Description & similar species WL 3-3.5mm. The blackish thorax and abdomen and<br />

smaller, strongly divergent lower calypters allow easy separation from A. acerba and<br />

it could be confused with Melanomya nana though the pubescent rather than plumose<br />

aristae, clearer wings and less elongate build should allow ready distinction. Males<br />

have grey dust patches on the sides of tergites 3-5 and the frons is about one-quarter<br />

the width of the head. That of the female is about one-third the width of the head.<br />

Pinned male Angioneura cyrtoneurina (left) with detail of head and thorax (right). Photos: Ian<br />

Andrews. Notice the broad frons of the male.<br />

20

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Variation None noted.<br />

Flight season June to August.<br />

Habitat & biology A species of marshy areas such as water meadows and seepagefed<br />

marsh, usually whewre base-rich waters are present. Reared from the snail<br />

Oxyloma sarsii (= Succinea elegans of older literature).<br />

Status & distribution Rare, with records from Wick, Hampshire (1945), Westbere,<br />

Kent (1966), Horning Ferry, Norfolk (1928-1952), Chippenham Fen, Cambridgeshire<br />

(1983), Minsmere RSPB Reserve, Suffolk (2001), Kennet Floodplain, Berkshire<br />

(2003) and a site in the Yorkshire Wolds (2015). Also rare in Europe.<br />

21

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Bellardia – emerald-bottles<br />

Medium-sized, rather robustly-built blowflies, usually with the tergites glossy<br />

greenish (sometimes bronze or turquoise-blue) but with a shifting dust pattern that<br />

mutes the colour. The thorax is more heavily grey-dusted with shifting stripes on the<br />

mesonotum but usually retains a trace of metallic colour. The lower calypters of most<br />

species have long upright hairs on basal section of the upper surface. The head<br />

capsule and antennae typically have an entirely dark ground colour (a little red can be<br />

present on the antennae) and never exhibit the extensive reddish or orange areas of<br />

many Calliphora species, and the antennae are much shorter. B. pubicornis (formerly<br />

Pseudonesia puberula) is aberrant in various respects, lacking metallic reflections,<br />

lacking hairs on the top of the lower calypters and having a rather protruding<br />

mouthedge.<br />

The biology is only known for a few species. Females are viviparous and the larvae<br />

develop as internal parasitoids of earthworms. B. bayeri appears to specifically select<br />

earthworms under loose bark of fallen trees and other dead wood. Most other species<br />

occur in a variety of habitats but B. pubicornis is strongly boreal and only found in the<br />

north and west of Scotland. Adults are occasional flower-visitors but are more likely<br />

to be seen on foliage.<br />

This is a Palaearctic genus with over 50 described species. A number of further<br />

species occur on the near continent (see Rognes, 1991 and Huijbregts, 2002) and B.<br />

bayeri is a fairly recent discovery in Britain. In addition to the potential for further<br />

Bellardia species to turn up, attention should also be drawn to Onesia floralis (also<br />

found on the near continent). It looks almost identical to a Bellardia in the field but<br />

has a no presutural intra-alar bristle but three postsutural ones (Bellardia species have<br />

a presutural one and two postsutural ones) and broader parafacialia.<br />

Male Bellardia are relatively easy to identify using genitalia (safer than using<br />

chaetotaxy) and checking genitalia is the best way to spot any extra species, including<br />

O. floralis.<br />

Key to species<br />

1 Tergites not obviously metallic-green, turquoise or bronze (at most a hint of<br />

bronze). Lower calypters usually without erect hairs on upper surface. Viewed<br />

from side, mouth edge clearly protruding further than the frons (Fig 1). Upcurved<br />

section of vein M relatively straight. Male genitalia Fig 6.......................pubicornis<br />

- Tergites obviously metallic-green, turquoise or bronze. Lower calypter with erect<br />

dark hairs on upper surface, at least basally. Viewed from side, mouth edge not,<br />

or barely, protruding further the frons (Fig 2). Upcurved section of vein M usually<br />

distinctly curved................. …………………………………………………….....2<br />

2 Front tibiae with two strong posteroventral bristles. Section of costa between the<br />

end of the subcosta and R1 with some ventral-facing hairs on lower surface (best<br />

seen by viewing the wing directly from the front). Male genitalia Fig 7…...pandia<br />

- Front tibiae with one posteroventral bristle. Section of costa between the end of<br />

the subcosta and R1 without anyventral-facing hairs on lower surface.…………..3<br />

22

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

3 Upper part of parafacialia with a dark spot that does not disappear when viewed<br />

tangentially from above (Fig 5). Calypters brownish-grey. Male genitalia Fig<br />

8….................................................……………………………………...……bayeri<br />

- Any dark mark on the upper part of parafacialia disappears with angle of view.<br />

Calypters yellowish-white………………..……….....................................……….4<br />

4 Tergite 4 viewed from the side with numerous upright or semi-upright bristly hairs<br />

most of which are almost as long as the marginals of tergite 3 and 4 (males) or<br />

clearly longer than the normal hairs of tergite 4 (females) (Fig 3). Basal wing<br />

veins usually blackish or dark brown, including on underside. Male genitalia Fig<br />

9……….......…..................................................................................…….…viarum<br />

- Tergite 4 viewed from side with shorter hairs, those of the male mostly only about<br />

half as long as the marginals of tergite 3 and 4 (Fig 4), those of the female of<br />

uniform length, inclined and normally without any longer outstanding hairs. Basal<br />

wing veins usually yellowish-brown on underside (especially in females). Male<br />

genitalia Fig 10............………………………………...........................…..vulgaris<br />

Bellardia bayeri (Jacentkowský, 1937)<br />

Bayer’s Emerald-bottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 4.5-7mm (check). A small Bellardia with<br />

metallic-turquoise tergites, resembling small specimens of B. viarum and B. vulgaris.<br />

The top of the parafacialia have a dark spot that remains visible, even when the head<br />

is viewed tangentially from above, and the calypters are brownish-grey. In the limited<br />

material seen the upturned section of vein M is relatively straight as in B. pubicornis.<br />

The male has very small genitalia.<br />

Variation Substantial size variation.<br />

Flight season On the continent it is recorded mainly in July and August but has been<br />

found in winter months. British records (some from malaise traps) suggest it flies here<br />

from spring until at least late summer.<br />

23

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Bellardia bayeri male (right, Photo: Andreas Haselböck) and female head (right). Notice the brownish<br />

lower calypter of the male and the dark mark at the top of the parafrontalia of the female.<br />

Habitat & biology Several British records are from woods featuring mature and<br />

fallen Beech trees. The Coventry female was found in a suburban kitchen at night,<br />

seemingly attracted by artificial lighting. In Russia it has been reared from the<br />

earthworm Eisenia foetida. In Britain it has been reared from puparia found under the<br />

bark of Beech whilst in Denmark it has been reared from a puparium found under elm<br />

bark.<br />

Status & distribution Known in Britain from Mark Ash Wood in the New Forest,<br />

Hampshire (1984), Newbattle Abbey, Midlothian (1994, pupa found under loose bark<br />

of a fallen Beech), Buckingham Palace Garden, London (several specimens from<br />

malaise trap samples in 1995), Burnham Beeches, Buckinghamshire (one male from a<br />

malaise trap in 1995 and another reared from a puparium found under bark of a Beech<br />

log), and Coventry, West Midlands (one female found indoors in a suburban house in<br />

2000). John Bowden (pers. comm.) also flagged a possible female specimen taken in<br />

Colchester in 1995, noting the brownish calypters and persistent spot on the face, but<br />

the location of the specimen is not known.<br />

Bellardia pandia (Walker, 1849)<br />

Bisetose Emerald-bottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 4.5-8.5mm. A typical-looking Bellardia with<br />

metallic-green tergites that have a shifting pattern of dusting, and a dark-grey thorax<br />

with shifting stripes and very slight metallic reflections. The pair of strong<br />

Bellardia pandia male (left) and pinned female (right). You can just see the two posteroventral bristles<br />

on the front tibia if you zoom into the male photo.<br />

24

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

posteroventral bristles on the front tibiae, and the male genitalia allow easy separation<br />

from B. viarum and B. vulgaris under magnification, but separating them in the field<br />

should not be attempted. The hairy underside to the costa between the end of the<br />

subcosta and R1 is another useful feature, especially where the front tibiae have been<br />

damaged or lost.<br />

Variation Considerable size variation. The metallic reflections of the tergites vary<br />

from greenish to bluish-turquoise.<br />

Flight season Late April to early September.<br />

Habitat & biology Found in a wide variety of habitats, especially damper ones,<br />

including coastal grazing, fens, damp woods and upland mires. Records from chalk<br />

downland may represent stragglers from damper habitats nearby. The biology is<br />

unconfirmed, though it is presumed to be an earthworm parasite.<br />

Status & distribution Found locally throughout Britain as far north as Ross &<br />

Cromarty and the Outer Hebrides.<br />

Bellardia pubicornis (Zetterstedt, 1838)<br />

Northern Bellardia<br />

Description & similar species WL 4.5-7mm. A small and rather aberrant Bellardia<br />

due to the lack of metallic coloration, the strongly produced mouthedge and<br />

(typically) the lack of any long hairs on the upper surface of the lower calypters. The<br />

mesonotum and tergites have a shifting pattern of grey and black, and the tergites can<br />

have a very slight hint of bronze. In the field, it could easily be overlooked as a<br />

tachinid.<br />

Variation Moderate size variation. The lower calypters occasionally have 1-2 hairs<br />

above.<br />

Flight season May to September.<br />

Habitat & biology Known from a range of upland habitats, especially moorland with<br />

exposed boulders among heather between 250-890 metres; also coastal dunes with<br />

dune heath. The biology is unknown. Adults characteristically rest on boulders and<br />

stones.<br />

Status & distribution A scarce species with records confined to the north and west of<br />

Scotland from Arran in the south to Elgin and Sutherland, also St Kilda.<br />

Bellardia pubicornis pinned female (left) and close up of abdomen (right)<br />

25

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Bellardia viarum (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830)<br />

Dark-veined Emerald-bottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 4.5-8.5mm. Superficially resembling B. pandia<br />

and B. vulgaris. Separation, especially from B. vulgaris, is best based on male<br />

genitalia (the outwardly-splayed surstyli of B.viarum are very different to the surstyli<br />

of B. vulgaris) as the hairs and bristles of the tergite 4 can become damaged, though<br />

in good material the hairs of tergite 4 are clearly longer than in B. vulgaris. The basal<br />

wing veins are usually blackish or dark brown both above and below.<br />

Variation Much as for B. pandia.<br />

Flight season Late April September.<br />

Habitat & biology Found in a similar range of habitats to B. pandia. The biology is<br />

unconfirmed, though it is presumed to be an earthworm parasite.<br />

Status & distribution Widespread and fairly frequent over much of Britain as far<br />

north as Easter Ross.<br />

Bellardia viarum male (left) and female (right). Notice the black rather than brown basal wing veins.<br />

Bellardia vulgaris (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830)<br />

Pale-veined Emerald-bottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 4.5-8.5mm. Closely resembling B. viarum and<br />

best distinguished using the male genitalia, though the basal wing veins are usually<br />

paler and the hairs on the disc of tergite 4 much shorter.<br />

Variation Much as for B. pandia.<br />

Flight season late April to October.<br />

Bellardia vulgaris pinned male (left) and female (right). Notice the brown rather than black basal wing<br />

veins.<br />

26

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Habitat & biology Found in a similar range of habitats to B. pandia and B. viarum<br />

and often flying alongside it. The biology is unconfirmed, though it is presumed to be<br />

an earthworm parasite.<br />

Status & distribution Widespread and fairly frequent over much of Britain as far<br />

north as the Inverness area and the Western Isles.<br />

27

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Calliphora – true bluebottles<br />

In a British context, these are the familiar bluebottles that often enter buildings and<br />

buzz about noisily. All of our species have metallic-blue tergites with a shifting dust<br />

pattern and a non-metallic, grey-dusted thorax, sometimes with shifting stripes. The<br />

upper surface of the lower calypters has long upright hairs which can cover most of<br />

the surface in species like C. vicina, C. vomitoria and C. uralensis, but rather less in<br />

the other three species. The face and antennae can be extensively reddish or orange.<br />

The antennae are longer than other metallic species except Cynomya and the aristae<br />

plumose. Non-metallic species occur abroad, notably in Australasia where some<br />

species are partially orange, reddish or golden-furred (some are termed ‘golden<br />

bottles’). The British species are relatively easily identified on external morphology<br />

alone but male genitalia can be useful when dealing with wet samples. Very small<br />

Calliphora individuals can be confused with Melinda species in the field but have<br />

longer antennae, usually an extensively orange face and, in species such as C. vicina<br />

and C. vomitoria, dark calypters.<br />

All species lay eggs on carrion and several species are important in forensic<br />

entomology. Different Calliphora species show subtly different preferences in the<br />

carrion they use and this has been studied in northern Britain (Davies 1990, 1999).<br />

Climate and temperature regimes also affect Calliphora assemblages, and diversity is<br />

higher in the north, notably in areas like the Cairngorms and Pennines where 5 of the<br />

6 British species can coexist. The only species unrecorded here, C. uralensis, is<br />

strongly associated with northern seabird colonies. All Calliphora species seem to be<br />

avid flower visitors and are also attracted to fresh excrement and Stinkhorn fungus.<br />

The synanthropic species such as C. vicina and to a lesser extent C. vomitoria and C.<br />

uralensis will also attempt to land on food and can be a nuisance and health hazard.<br />

They can also breed in garbage and poorly stored food containing meat and dairy<br />

products.<br />

This is one of the largest blowfly genera (about 150 species) with an occurrence<br />

centred on the Holarctic plus Australasian regions. C. genarum seems to be the only<br />

further species found on the near continent and resembles C. stelviana but has shorter<br />

aristal hairs, a dark face and a non-enlarged male postabdomen (see Marshall et. al.<br />

2011, which is available online, for images). However, synanthropic North American<br />

species such as C. livida (which resembles C. uralensis but has 3 postsutural intraalars)<br />

could easily be bought over and would be easy to overlook. See Marshall et. al.<br />

(loc. cit.) for a full account of the Calliphora species of Eastern Canada.<br />

Key to species<br />

1 Basicostae mostly pale brown, at least on apical half. Anterior thoracic spiracle<br />

orange. Genal dilation pale brown on anterior two-thirds, dark grey on posterior<br />

third, and entirely covered with black hairs. Male genitalia Fig 11.................vicina<br />

- Basicostae blackish and anterior thoracic spiracle brownish or blackish. Genal<br />

dilation usually entirely darkened (except some C. uralensis)............................…2<br />

2 Calypters white or very pale grey, the upper calypter with a whitish or pale grey<br />

rim. Build relatively slim, the abdomen clearly longer than wide in males, as long<br />

28

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

as wide in females. Tip of male abdomen bulbous in side view with sternite 5<br />

produced into two large projecting lobes (Fig 1)…….............................................3<br />

- Calypters infuscated grey or brownish, the upper calypter with a dark grey or<br />

blackish rim. Build more robust, the abdomen as wide as long, or wider (except<br />

male loewi where it can be a little longer then wide). Male genitalia not noticeably<br />

enlarged, the lobes of sternite 5 small (Fig 2)…………….................................….4<br />

3 Scutellum with 4-5 pairs of strong marginals in addition to the apicals (Fig 7).<br />

Mesonotum with distinct stripes (very obvious when viewed from behind). Male<br />

mid tibiae without a ventral bristle; the eyes separated by about the width of a<br />

third antennal segment, the interfrontalia narrower than the parafrontalia (Fig 3).<br />

Averaging larger (wing length to 10mm) and without an orbital bristle on each<br />

side of the ocellar triangle. Male genitalia Fig 9…....................…...…….subalpina<br />

- Scutellum with only 2-3 pairs of strong marginals in addition to the apicals (Fig<br />

8). Mesonotum without distinct stripes (only weak ones appearing when viewed<br />

from behind). Male mid tibiae with a ventral bristle; the eyes separated by about<br />

29

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

1.5 times the width of a third antennal segment, the interfrontalia wider than the<br />

parafrontalia and with an orbital bristle on each side of the ocellar triangle (Fig 4).<br />

Averaging smaller (wing length to 9mm). Male genitalia Fig 10…......….stelviana<br />

4 Genae extensively orange-haired. Male genitalia Fig 12...........…..……..vomitoria<br />

- Genae black-haired..………………………......…………………………………..5<br />

5 Mesonotum with a dark median stripe running between the acrostichals and<br />

weaker shifting dark stripes running down the dorsocentral and intra-alar rows.<br />

Top of parafacialia with a black and silvery-white spot when viewed from certain<br />

angles, the genae blackish with light dusting and shining from some angles.<br />

Female tergite 5 deeply notched apically (Fig 5). Male genitalia Fig 13... …..loewi<br />

- Mesonotum without distinct stripes. Top of parafacialia never producing a silvery,<br />

reflective spot, the genae brown or blackish but dulled by thick dusting. Female<br />

tergite 5 not deeply notched apically (Fig 6). Male genitalia Fig 14……..uralensis<br />

Calliphora loewi Enderlein, 1903<br />

Long-horned Bluebottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 6-10 mm. The stripy mesonotum means that this<br />

species could be overlooked in the field as C. subalpina, so care should be taken to<br />

check for the darker squamae and less swollen male genitalia. Males of C. loewi also<br />

have a narrower frons (about 0.75 the width of a third antennal segment). Their build<br />

is slimmer than species such as C. vicina and C. vomitoria but a little stouter than C.<br />

subalpina. Females are readily identified under the microscope by the deep cleft along<br />

the hind margin of tergite 5 (much deeper than any other Calliphora). They have the<br />

longest third antennal segment of any Calliphora, about five times as long as wide<br />

and only ending a little short of the mouth edge. Both sexes have a shifting silverywhite<br />

mark at the top of the parafacialia and the genal dilations are entirely dark with<br />

rather light dusting that allows them to shine from some angles.<br />

Variation The ground colour of the face and frons varies from entirely dark to having<br />

the front of the frons, much of the parafacialia and the parts of genae surrounding the<br />

dark genal dilation orange a female - check if this applies to both sexes.<br />

Flight season May to September.<br />

Calliphora loewi male (left) and female (right) showing the striped thorax combined with dark<br />

calypters. Notice the silvery mark at the top of the female's parafacialia and her particularly long<br />

antennae.<br />

30

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Habitat & biology Typically moorland and upland woods, between 455 and 740<br />

metres in Wales but some lowland sites further north (e.g. Davies & Laurence, 1992).<br />

The larvae develop in assorted carrion. It is not particularly synanthropic.<br />

Status & distribution A northern and western species with records concentrated in<br />

the Scottish Highlands (where fairly frequent and occuring north to Orkney) but<br />

extending south to the Peak District and the Black Mountains of Breconshire.<br />

Calliphora stelviana (Brauer & von Bergenstamm, 1891)<br />

Little Bluebottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 5-9mm. A relatively small, slimly-built<br />

Calliphora without conspicuous striping on the mesonotum and with white calypters.<br />

The genal dilations are mostly dark but the face extensively yellow. The scutellum<br />

only has 2-3 strong marginals (4-5 in all other Calliphora). Males resemble C.<br />

subalpina in having an enlarged abdominal tip with expanded lobes arising from<br />

sternite 5, though these lobes are not quite as large as in C. subalpina. The male eyes<br />

are separated by about twice the width of a third antennal segment, resulting in a<br />

wider frons than other male Calliphora.<br />

Variation Check more material<br />

Flight season British records extend from early June to late September.<br />

Habitat & biology Upland and montane areas mostly between 530 to 1070 metres,<br />

including tall Calluna heath, Racomitrium moss-heath and the subalpine zone where<br />

scattered trees are present (Horsfield, 2002). Larvae mostly develop in the carcasses<br />

of small mammals such as shrews, voles and mice. Horsfield (loc. cit.) had<br />

considerable success in recording adults throughout the Scottish Highlands using<br />

water bowl traps.<br />

Status & distribution A scarce species with records confined to the Scottish<br />

Highlands and a few sites in the northern Pennines. Even in areas where it occurs with<br />

the related C. subalpina, C. stelviana clearly prefers higher altitudes (Davies &<br />

Laurence, loc. cit.).<br />

Calliphora stelviana pinned males showing the widely separated eyes (left) and swollen tip to the<br />

abdomen (right image: Knut Rognes)<br />

31

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016<br />

Calliphora subalpina (Ringdahl, 1931)<br />

Woodland Bluebottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 7-10mm. A rather slimly-built Calliphora,<br />

especially males, and one of two species with a distinctly striped mesonotum.<br />

Distinguished from the other, C. loewi (alongside which it can occur), by the whitish<br />

calypters, predominantly orange ground colour to the face, much expanded tip to the<br />

male abdomen (with greatly enlarged lobes arising from sternite 5), and lack of a deep<br />

cleft on the hind margin of the female’s tergite 5. The male eyes are separated by<br />

about the width of a third antennal segment.<br />

Variation Substantial size variation. The interfrontalia and third antennal segments of<br />

both sexes can vary from mostly reddish to mostly dark.<br />

Flight season May to October.<br />

Habitat & biology Strongly attached to woods over much of its range, especially<br />

damp/humid ones but recorded from moorland as high as 500 metres in area such as<br />

the Derbyshire Peaks and North Wales (Davies & Laurence, loc. cit.). It visits flowers<br />

such as Hogweed, Angelica and brambles, also Stinkhorn fungus. It also sunbathes on<br />

foliage along the edges of rides and clearings. The larvae develop in assorted carrion.<br />

It has been recorded in gardens and urban greenspace of various sorts but is not<br />

particularly synanthropic.<br />

Status & distribution Widespread in the north and west but extending to lowland<br />

areas as far south as Herefordshire and Warwickshire. Fairly frequent in the Scottish<br />

Highlands. Almost completely absent from SE England (there is a single Colchester<br />

record from John Bowden).<br />

Calliphora subalpina male (left) and female (right) showing the striped thorax combined with whitish<br />

calypters<br />

Calliphora uralensis Villeneuve, 1922<br />

Seabird Bluebottle<br />

Description & similar species WL 6-10mm. Resembling C. vicina in the field<br />

(alongside which it usually flies) but the dark basicostae and dark anterior thoracic<br />

spiracles allow ready separation under a microscope or a strong hand lens, and the<br />

genae are more extensively darkened. The male eyes are separated by the width of a<br />

third antennal segment.<br />