201106

201106

201106

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

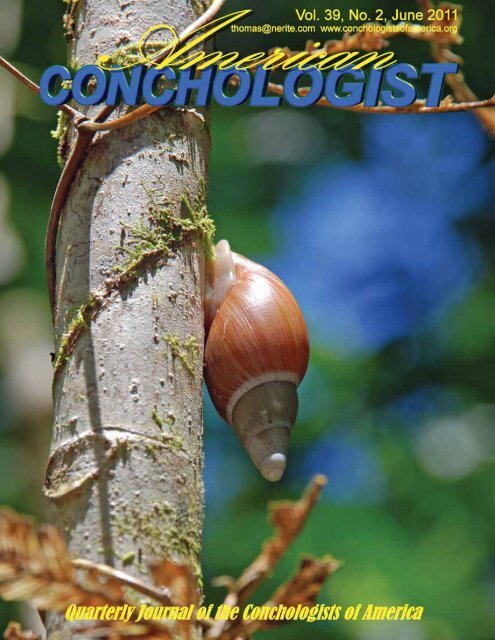

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 3In This IssueLetters and Comments ----------------------------------------------- 3In the thick of it: the jungles of the Solomon Islandsby Simon Aiken -------------------------------------------------------- 4Threetooth ID ruminations open a centuries-oldamphi-Atlantic Pandora’s Box by Harry G. Lee --------------- 13Dealer Directory ----------------------------------------------------- 18Mid-Atlantic Malacologists Meeting by Elizabeth Shea,Leslie Skibinski, & Aydin Örstan ----------------------------------202011 Sarasota Shell Club Shell Show by Ron Bopp ----------- 222011 Broward Shell Club Shell Show by Nancy Galdo ------- 24St. Petersburg Shell Club Shell Show ---------------------------- 25Editor’s Comments: This is the first 40-page issue ofAmerican Conchologist; thanks to Johnson Press of America,Inc., of Pontiac, IL, and to the many folks who submitted articles.My thanks to all who submitted articles and apologiesto those who I had to bump back to the next issue. Hang inthere, I will get to everybody.After the last issue, I received a couple of interestingletters from Tom Rice. Some of what he had to say issummarized below and some resulted in the article on page27, “What is a shell worth,” by Tom. One of the expensiveshells he mentions is a rare cowrie, Austrasiatica alexhuberti(Lorenz & Hubert, 2000). The other shell he mentions is asinistral Turbinella pyrum (Linnaeus, 1758). The Turbinellaor sacred chank, is discussed in Tom’s article and in a greatfollow-on article by Harry Lee, one of the very few peoplewho actually owns a sinistral sacred chank (page 28). Forthose who may wonder what one of the most expensive shellsin the world looks like, you can see a left-handed Turbinellapyrum on page 28 and the Austrasiatica alexhuberti below,courtesy of Felix Lorenz, who has probably handled more ofthese than anyone else in the world.October 2010 British Shell Collectors’ ClubShell Show ------------------------------------------------------------- 26Oregon Society of Conchologists Shell Show ------------------- 27What is a shell worth? by Tom Rice ------------------------------ 27Historical notes on a sinistral sacred chank: Turbinellapyrum by Harry G. Lee --------------------------------------------- 28SCUM XV: Southern California Unified Malacologistsby Lindsey T. Groves ------------------------------------------------ 30Interesting boring by He Jing -------------------------------------- 32Book Review: “Mattheus Marinus Schepman (1847-1919)and His Contributions to Malacology” -------------------------- 37Book Review: Compendium of Florida Fossil Shells,Volume 1, Middle Miocene to Late PleistoceneMarine Gastropods -------------------------------------------------- 38Book Review: Shells of the Hawaiian Islands, Vol. 1,The Sea Shells; Vol. 2, The Land Shells -------------------------- 39Front Cover: Placostylus strangei (Pfeiffer, 1855) a ratherhandsome tree snail in the family Bulimulidae on a treein the Solomon Islands. For more about these islands andthe land snails and other wildlife that abound there, seeSimon Aiken’s article on page 4.Back Cover: The Shell Collectors, acrylic on canvas, 36”x 60,” painted by COA member David Herman of EastMeadow, New York. Regretfully, it had to be cropped abit to fit the back cover, but I think it still conveys a senseof the expanse of a seashore.Dear Tom,Just received the March American Conchologist andhave enjoyed all the articles. Especially George Metz’s onparasitic mollusks. I would like to draw attention to anothergroup, referred to as kleptoparasitic mollusks in the familyTrichotropidae. Erika Lyengar has studied these and we havean article and video on our web site concerning them: www.ofseaandshore.com/news/kleptopaper/kleptopaper.phpRe: “Conch shells on coins” by Jesse Todd inAmerican Conchologist 39(1). A previous article might beof interest to Amer. Conch. readers, “Mollusks on Coins” byWolfgang Fischer. Originally it appeared in Club ConchyliaInformationen 31(1-2) 1999, and was reprinted in Of Sea andShore 23(1): 37-42 (2000). That issue of OS&S (as well asVol. 1 #1 through Vol. 23 #3) can be accessed on our web site(better, clearer images of all issues Vol. 1 #1 through Vol. 27#4 available on DVD as well - info on web site).Tom Rice -- Rawai Beach, Phuket, Thailand

Page 4 Vol. 39, No. 2In the thick of it:The jungles of the Solomon IslandsSimon Aiken“But we have nobody to cook!” exclaimedthe owner of the town’s only restaurant, excusingwhy they were closed at dinner time. No doubt thisdelicious ambiguity was unintentional, in a countrynotorious for cannibalism well into the 20th Century,but it shows what the modern traveler in theSolomon Islands must expect. And I was in the thirdlargest town in the country.In a previous American Conchologist(March 2011, vol. 39, no. 1) I wrote of my questfor seashells in the Solomon Islands, a huge archipelagoalmost untouched by tourism. Flying overthe larger islands reveals steep mountains coveredin dense jungle with no roads and almost no inlandsettlements. Except in a few areas, there has beenlittle deforestation, so 90% of the country is rainforest.It is challenging terrain, to be sure, but very promising for thelandsnail collector. A good machete is essential; a relaxed attitudeto hygiene is helpful. Swampy areas in the jungle are popular withleeches; innocuous looking plants such as the nalato and hailasiwill cause serious blisters if touched. The jungle is divided byfast-flowing streams and rivers, and trails are prone to flashflooding.The ‘roads’ (apart from in Honiara) are still made from deadcoral – they were constructed by US Navy Seabees in the 1940sand there has been no reason to upgrade them.The Marau area of Guadalcanal holds the dubious title ofthe second wettest place on earth. A year’s rainfall here can be 500inches – ten times the annual drenching of Florida. The soil is richand volcanic, with some limestone areas. Promising habitats forsnails, certainly, and one must wonder how many exotic speciesawait discovery in these almost impenetrable rainforests. I couldsay that my most successful landsnail collecting was in the rain,but it was almost always raining!The range of molluscan fauna in the Solomons bears similaritiesto New Guinea and the Bougainville Islands, but there isa high proportion of endemic species. The colorful Papuina andMegalacron are varied and conspicuous and many are endemicto just one island. The migration of species has generally beeneastwards – from Malaysia, through New Guinea, and then downthrough the Solomons.There are relatively few mammals in these islands. Thereare several species of rat, but the larger tree-climbing ones (biggerthan domestic cats!) are endangered or extinct. The main predatorsof snails are presumably birds, and the Solomons certainlyhas a rich ornithological fauna. The 3-foot-long Blyth’s hornbill(Aceros plicatus Forst, 1781) is common in the forest canopy,especially in New Georgia province. This noisy omnivorous birdis the most easterly of the world’s hornbills.Most Solomon Islanders live in small villages on thecoast. The rainforest is so dense that travel between villages is bydug-out canoe. The median size of a settlement is just 41 peopleand perhaps it is this emphasis on small close-knit communitiesthat has helped preserve many traditional aspects of their life.Society is matrilineal, with land inherited through the femaleline, a tradition stemming from head-hunting days when so manyyoung men died violent deaths. There is no electricity outside ofa handful of towns, and no running water. Houses are still builtof raw materials from the jungle. A few years ago there was alittle migration from coastal villages to inland sites in response toPrinted RedA century ago, the author Jack London warned of the dangers:“The Solomons ought to be printed red on the charts – andyellow, too, for the diseases.” (Adventure, 1911)Head-hunting and cannibalism were real dangers then, particularlyin New Georgia – but, thankfully, not any more. Tropicaldiseases certainly remain a concern for the modern travelerthough. The Solomonsis one of the worst countriesin the world for malaria,with drug-resistantstrains abounding. Evenwith hospital treatment,malaria is often fatalhere. For any visitor,preventative treatmentwith atovaquone andproguanil is stronglyrecommended. Typhoid,hepatitis A, and denguefever are also widespread.

Page 6 Vol. 39, No. 2(Above) Most references describe this species as Papuina vexillaris, but the true name is P. fringilla (Pfeiffer, 1855) – a longstandingconfusion that has been perpetuated by shell dealers. Two contrasting forms are well known, shown here with thelive animals in the jungle several miles from Munda, New Georgia. The best-known form has a prominent purple/rose lip anda similarly colored apex. Alternatively, the whole shell is cream with a white lip, often with a less-rounded body whorl. I was,however, able to find other important variations. Some purple-lipped specimens do indeed have a white apex (top row, secondspecimen), and I found two specimens with a purple apex but white lip (top row, fifth specimen). Multi-banded forms (bottomrow) or shells with brown or pink body whorls are also rare. The variations shown here range from 19mm to 25mm.“The War Is Over!”The Solomons…this is the country where it took until 1965 to convince Japanese soldiers that WWII was over. There were reportsof aged Japanese soldiers ‘holding out’ in the jungle as late as 1989. Such are the difficulties with linguistics, transport, and impenetrablejungle that communicating across this island nation has always been problematic. Nowadays, phones are rare outside Honiara;internet access is difficult in Honiara and impossible elsewhere; there are only a handful of post offices spread across half-a-millionsquare miles of Oceania; and there are 63 official languages. It is perhaps because of the communication problems that traditionalvillage life survives in the Solomons.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 7(Above) This is the ‘real’ Papuina vexillaris (Pfeiffer, 1855),also from Munda (24–25mm). Although the shells familiar tocollectors are pure white, in life the shell is covered in a layerof algae – which presumably aids camouflage. Very carefulcleaning can preserve much of this green algae (top right).(Above) Chloritis eustoma Pfeiffer, 1842 (18.7mm) has a flakybrown periostracum, covered in tiny hairs. The few live specimensI found in Guadalcanal and New Georgia proved difficultto clean without damaging the periostracum.(Below) In the Roviana language of Munda, a snail is ‘suloco.’The most conspicuous suloco to the townspeople of Munda isDendrotrochus helicinoides cleryi (Récluz, 1851), which lives ontrees and bushes in the town itself. The specimens here (13.7–19.2mm) show the range of colors, patterns, and size. In Guadalcanal,I collected the relatively unpatterned nominate form.(Above) These are three of the rarer Papuina I collected in NewGeorgia: (1) Papuina lienardiana Cross, 1864, 18.5mm; (2) P.eros Angas, 1867, 18.5mm; (3) P. eddystonensis (Reeve, 1854),19.9mm. Each is remarkably similar in shape.(Above) A highlight of the trip was finding this Papuina indense jungle a few miles from Munda. It appears to be anundescribed species. Unfortunately I found only two adultspecimens, but the species will be described this year byAndré Delsaerdt. The specimen shown here (24.4mm) will bea paratype. Finding a new land species just a few miles inlandmakes one wonder how many new species await discovery inthese islands.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 9(Above) Trochomorpha xiphias rubianaensis Clapp, 1923 is oneof the most beautiful of its genus. These shells (17.7–18.9mm)were collected around the town of Munda.(Above) The operculate family Cyclophoridae is well representedin the Solomons. This easily overlooked species is one ofthe smallest: Pseudocyclotus levis (Pfeiffer, 1855). The cleanedshell is only 7.3mm and was collected in the jungles of NewGeorgia.This widespread butinconspicuous snail isOmphalotropis nebulosa(Pease, 1872), in theprosobranch family Assimineidae.I collectedspecimens on bushes inMunda town. At 9.1mm,this specimen is a veritablegiant!(Above) The widely distributed Palaeohelicina moquiniana(Récluz, 1851) is found in three distinct color forms in the Solomons.These specimens (8.6–8.9mm) are from the Munda areain New Georgia.(Above) “If you go down to the woods today,” even after 68years have passed, you may well come across one of these. Thisparticular ‘specimen’ was found in thick jungle while huntingPapuina. Controlled detonations of WWII bombs are analmost weekly occurrence around Munda. Coke bottles fromthe 1940s are still strewn throughout the jungle and relics suchas ‘dog tags’ are often found.(Above) Palaeohelicina spinifera (Pfeiffer, 1855) is a muchmore secretive species, inhabiting dark and damp corners inthe jungle. There are several contrasting color forms. Thethree specimens here (13.6–15.0mm) were collected in Marau;the live animal is slightly sub-adult.

Page 10 Vol. 39, No. 2(Above) The author examines Leptopoma woodfordi Sowerby,1889 on a leaf in the jungle of Marau. At right: (1) L. woodfordi,16.9mm; (2) L. dohrni (Adams & Angas, 1864), 16.4mm,also from Marau; and (3) L. perlucida (Grateloup, 1840),13.4mm, from New Georgia. The animal of L. perlucida is astriking yellow color.(Above) In Suhu village, Marau, a boy shins up a coconutpalm, an essential skill for Solomon Islanders. Coconuts aregrown in most coastal regions. There are, however, very few‘plantations,’ except on the plains region of northern Guadalcanal.The coconut palm is integral to the islanders’ way oflife. The ‘milk’ is a readily available and cooling drink. Aswell as eating the flesh, it is dried into ‘copra’ in each village,which is the principal cash crop. The fronds become buildingmaterials and the ‘coir’ (husk fiber) is made into rope.(Above-left) A typical Marau house in Vutu village. Traditionalbuilding materials and methods are still the standard.The tropical rain is so heavy that flash floods are commonthroughout the year, hence all houses are built on ‘stilts.’ Thefrequent flooding means there are rather few ground-dwellingmolluscan species in the Solomons. One exception is Subulinaoctona (Bruguière, 1792), shown on the right. In this 20.9mmspecimen, two eggs are clearly visible.(Above) The Solomons is a delight for arachnophiles. Argiopekeyserlingi Karsch, 1878, is often known as the “St Andrew’sCross spider.” Spiders of this genus typically hold their legsin pairs so as to form an ‘X’ shape, with their head pointeddownwards.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 11(Above) Variation in Neritodryas cornea (1–6; 21–25mm) fromthe Marau jungle. It is likely that the variety with a yellowaperture (6) will be described as a separate species in the future.Neritodryas subsulcata (Sowerby, 1836) (7, 8; 24mm) is arelated species that can easily be confused with N. cornea. Theblack mottling on the parietal shelf of N. subsulcata is characteristic.Both of these species are primarily arboreal, yet thereare plenty of data slips in existence that incorrectly list “freshwaterstream” or “lake” as the habitat. On the other hand,little is known of the reproductive traits of this genus and it isprobable that they return to water to lay eggs.(Above) George from Suhu village collects in the Marau jungle.The shell he is reaching – at 8ft off the ground – is the ‘freshwater’snail Neritodryas cornea (Linnaeus, 1758). A completesurprise in this habitat was that a supposed freshwater speciesexploited such a niche; live Neritodryas were common amongthis vegetation, a considerable distance from flowing water.(Above) This bizarre spiny-backed orb-weaver (Gasteracanthasp.) was widespread and common. The islanders believe it isvenomous.(Above) Thiara cancellata Röding, 1798, is neither rare nor endemicto the Solomons. Finding specimens with their spinesintact was truly satisfying, however. This 30.7mm specimen isfrom the Vilavila River in Guadalcanal. As the river flows outinto Marau Sound it joins the Vainihaka River and several interestingfreshwater species are found: Thiara winteri von demBusch, 1842; Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1822); Melanoidesaspirans (Hinds, 1847); the ubiquitous Faunus ater (Linnaeus,1758); Neripteron dilatatum (Broderip, 1833); Neritina variegata(Lesson, 1831); long-spined Clithon donovani Récluz, 1843;Septaria porcellana (Linnaeus, 1758); and the endemic bivalveHyridella guppyi (Smith, 1885).

Page 12 Vol. 39, No. 2(Above) The giant helmeted katydid (Phyllophorella woodfordiKirby, 1899) is an expert at camouflage. This individual wasspotted in a thickly-forested swamp in Marau.(Above) A green-bellied tree skink, Emoia cyanogaster (Lesson,1826), in the jungle on New Georgia. A much larger cousin ofthis small lizard is the endemic Solomon Islands skink Coruciazebrata Gray, 1856, a nocturnal herbivore with a prehensiletail. At 31 inches it is the largest skink in the world.Throughout my travels in the Solomons I found the villagers friendly, very hospitable, and more than willing to help collectshells – especially the children. This photo shows the people of Suhu village, gathered on the beach after a day of collectingoe. My sincere thanks to the people of Suhu, Vutu, and Hautahe in Marau, especially Morris, Priscilla, George, and Joe, andall the villagers of Kiapatu in New Georgia, especially Sycamore and his family. For assistance with this article I thank TomEichhorst, Mike McCoy, and G. Thomas Watters. In particular, I thank André Delsaerdt for his expert help with the identificationof Solomon Island landsnails.All photographs appear courtesy of Simon’s Specimen Shells Ltd (www.simons-specimen-shells.com)Simon Aikensimonaiken@btinternet.com

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 13Threetooth ID ruminations open a centuries-oldamphi-Atlantic Pandora’s BoxHarry G. LeeTriodopsis messana Hubricht, 1952, pinhole three-tooth, Georgia, Upsom Co., Thomaston, Roland Rd., ca. 7 miles W town, underfallen limb resting on cleared area immediately adjacent to lawn. Collected by Billie Brown, 30 October 2010.The genus Triodopsis Rafinesque, 1819: 425, as currentlyinterpreted (Emberton, 1988), is widely distributed in easternNorth America, particularly the southeastern US. The type speciesof the genus, T. lunula Rafinesque, 1831 (= Helix tridentata Say,1817), is a story in itself. (See the note on the type of Triodopsisbeginning on p. 14.) The conchological identification of theslightly fewer than 30 species of these so-called “threetooths” isbased on apertural dentition, tightness of coil, umbilical diameter,axial sculpture, pigmentation of fresh material, and zoogeography(see ). That may seemsimple enough, but other factors add a degree of difficulty possiblyunique to this genus. There is convincing evidence of hybridizationamong species and, consequent in part to the ability ofsome taxa to prosper in human-altered environments, numerousanthropogenic introductions have confused what was certainly amore orderly zoogeographic mosaic before the European immigration.Furthermore, significant intraspecific variation, evident evenwithin a single population, may add complexity.On the other hand, last year Bill Frank and I created asimple compendium of single images of each of the 28 generallyrecognizedspecies of threetooths (cited above), so I thought identificationof four living threetooths taken by Jacksonville Shell Club(JSC) member Billie Brown in Thomaston, Georgia, would begreatly facilitated. Hours later, I realized that “greatly” was a bit agenerous for a description of the ultimate campaign. For openers,these snails didn’t quite match anything in the website portfolio!After ransacking my library, I found a much better match - es-sentially perfect: paratypes of T. affinis Hubricht, 1954, figured byGrimm (1975: fig 2D). T. affinis is regarded by certain authoritiesas a stable hybrid between T. fallax (Say, 1825) and T. alabamensis(Pilsbry, 1902) and not recognized by Turgeon, Quinn,et al. (1998: 153). Almost satisfied, I then delved a little deeperand found that Hubricht (1954: 28-30) stated “the only differencebetween T. messana Hubricht and T. f. affinis is in the color.” Asunusual as this dependence on shell coloration struck me, Grimm(1975) seemed to have been in agreement. Next, the original descriptionswere consulted. Hubricht (1952: 80-81) characterizedT. messana as “reddish brown” [later “dark red-brown to walnutbrown” by Grimm (1975)]. The largest in his cited type series(five) was 15.0mm in maximum diameter, and he remarked on thevariability of the outer lip tooth, in some “pointed and little if anyinflected; in others broadly rounded and deep-seated.” He citedPilsbry (1940: 810: fig. 480 C), but did not otherwise figure thisspecies. In his description of T. fallax affinis (Hubricht, 1954), heused “deep olive buff to wood brown” to describe the shell, thelargest of his cited type series (five) was 13.3mm, and no figurewas provided.Both the latter taxa are anthropochorous, meaning able tolive in human-altered environments (Hubricht, 1952, 1954, 1971,1984, 1985; Grimm, 1975), which is consistent with the habitat inwhich Billie collected her snails. Both species potentially occurin Upson Co., GA (Hubricht, 1985), where the topical specimenswere found, and neither seems to have an authentic figure otherthan those cited, all graytones. On the one hand, her shells match

Page 16 Vol. 39, No. 21. Triodopsis alabamensis (Pilsbry, 1902), Alabama Threetooth (PutnamCo., GA) [S VA to SE TN & SE AL].2. Triodopsis anteridon Pilsbry, 1940, Carter Threetooth (WyomingCo., WV - Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH) 264768) [E KY,SW WV & VA to NE TN].3. Triodopsis burchi Hubricht, 1950, Pittsylvania Threetooth (RoanokeCo., VA - FMNH 266240) [VA & NC].4. Triodopsis claibornensis Lutz, 1950, Claiborne Threetooth (CampbellCo., TN - FLMNH 264399) [NE TN].5. Triodopsis cragini Call, 1886, Post Oak Threetooth (Claiborne Parish,LA - FMNH 266248) [SW MO & SE MO to E TX & W LA].6. Triodopsis complanata (Pilsbry, 1898), Glossy Threetooth (PulaskiCo., KY - FMNH 266277) [SC KY & NC TN].7. Triodopsis discoidea (Pilsbry, 1904), Rivercliff Threetooth (CrawfordCo., IN) [SW OH to SE MO].8. Triodopsis fallax (Say, 1825), Mimic Threetooth (Camden Co., NJ)[PA to TN & NC].9. Triodopsis fulciden Hubricht, 1952, Dwarf Threetooth (CatawbaCo., NC - [PARATYPE] FMNH 266316) [SW NC].10. Triodopsis fraudulenta (Pilsbry, 1894), Baffled Threetooth (RockbridgeCo., VA) [PA, WV, & VA].11. Triodopsis henriettae (Mazÿck, 1877), Pineywoods Threetooth(Brazos Co., TX - FMNH 266325) [NE TX].12. Triodopsis hopetonensis (Shuttleworth, 1852), Magnolia Threetooth(Davidson Co., TN) [most of the SE].13. Triodopsis juxtidens (Pilsbry, 1894), Atlantic Threetooth (DurhamCo., NC) [NJ to WV & GA].14. Triodopsis messana Hubricht, 1952, Pinhole Threetooth (HorryCo., SC) [VA to FL].15. Triodopsis neglecta (Pilsbry, 1899), Ozark Threetooth (Barry Co.,MO) [MO, KS, OK, & AR].16. Triodopsis obsoleta (Pilsbry, 1894), Nubbin Threetooth (Dare Co.,NC) [MD to E NC].

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 1717. Triodopsis palustris Hubricht, 1958, Santee Threetooth, (LongCo., GA) [E SC to NE FL].18. Triodopsis pendula Hubricht, 1952, Hanging Rock Threetooth(Iredell Co., NC - FMNH 266352) [WC NC].19. Triodopsis picea Hubricht, 1958, Spruce Knob Threetooth (PocahontasCo., WV - FMNH 266426) [SW PA & WV].20. Triodopsis platysayoides (Brooks, 1933), Cheat Threetooth(Monongalia Co., WV - FMNH 266693) [N WV].21. Triodopsis rugosa Brooks and MacMillan, 1940, ButtressedThreetooth (Logan Co., WV - FMNH 264690) [SW WV].22. Triodopsis soelneri (Henderson, 1907), Cape Fear Threetooth (ColumbusCo., NC) [SE NC];23. Triodopsis tennesseensis (Walker and Pilsbry, 1902), BuddedThreetooth (Cleburne Co., AL) [SW VA & SE TN to E AL].24. Triodopsis tridentata (Say, 1816), Northern Threetooth (MitchellCo., NC) [NH & MI to GA & MS].25. Triodopsis tridentata (Say, 1817), form edentilabris Pilsbry, 1894,Northern Threetooth [toothless morph] (Haywood Co., NC) [sporadicNH & MI to GA & MS].26. Triodopsis vannostrandi (Bland, 1875), Coiled Threetooth (OkaloosaCo., FL) [SC to FL & AL].27. Triodopsis vulgata Pilsbry, 1940, Dished Threetooth (Nelson Co.,KY) [W NY & WI to GA & MS].28. Triodopsis vultuosa (Gould, 1848), Texas Threetooth (Marion Co.,AR) [E TX & SW LA].I thank Drs. Jochen Gerber and Stephanie Clark of the Field Museumof Natural History (Chicago) for curatorial and technical assistancein the production of this plate. Bill Frank and Tom Eichhorstprovided further editorial services. The geographic ranges [in brackets]are based on Hubricht (1985) with minor modifications based onunpublished data. Harry G. Lee

Page 18 Vol. 39, No. 2

Page 20 Vol. 39, No. 2Mid-Atlantic Malacologists MeetingElizabeth K. Shea 1 , Leslie Skibinski 1 and Aydin Örstan 21Department of Mollusks, Delaware Museum of Natural History, Wilmington, DE 190102Research Associate, Section of Mollusks, Carnegie Museum of Natural HistoryPittsburgh, PA, U.S.AFig. 1 Mid-Atlantic Malacologists participants photographed outside the Delaware Museum of Natural History. Picture courtesyof Happy and Robert Robertson.Back row: Bill Fenzan, Charlie Sturm, Phil Fallon, Colleen Sinclair Winters, Tim Pearce, Tom Grace, Makiri Sei, Paul Callomon,John Kucker, John Wolff, Kevin Ripka, Matt Blaine, Clem CountsMiddle row: Francisco Borrero, Robert Robertson, Al Spoo, Adam Baldinger, Leslie Skibinski, Paula Mikkelsen, Amanda Lawless,Elaina McDonald, Judy Goldberg, Lois Kucker, Happy Robertson, Dona BlaineFront row: Megan Paustian, Laura Zeller, Liz Shea, Marla Coppolino, Aydin Örstan, Beysun ÖrstanThe Mid-Atlantic Malacologists (MAM) Meeting washeld on March 19, 2011, at the Delaware Museum of Natural Historyin Wilmington, DE. Thirty-four professional, amateur, novice,and experienced malacologists were in attendance (Fig. 1). Asusual, we drew from a large geographical range, with participantsfrom Norfolk, VA, Cambridge, MA, and Cincinnati, OH, includedin our definition of Mid-Atlantic.This informal meeting, and its sister-meetings: SouthernCalifornia Unified Malacologists (SCUM), Bay Area Malacologists(BAM), Ohio Valley Unified Malacologists (OVUM), andnow the Florida United Malacologists (FUM), serve as a mixingbowl of molluscan people and topics. Emeritus curators mix withartists and university faculty meet shell club members. The talksare always an eclectic mix of What’s Happening Now in malacology.This year was no exception – we heard an audio recording ofland snails eating carrots, learned about designing snail identificationsoftware for an iPhone (there’s an app for that!), and how theAcademy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia is using “Wall-E,” acomputer with voice recognition software lashed to a hospital cartto inventory their collection for the first time in 200 years. All inall, 16 full talks and 1 poster were presented, and 10 people usedthe Mollusk collection and library.The following list of speakers and brief summaries oftheir presentations, known as the “Bootleg Transactions,” can befound on Aydin’s blog: http://snailstales.blogspot.com/2011/03/bootleg-transactions-of-13th-mam.htmlAdditional comments are welcome!• Marla Coppolino (New York): Marla played the raspingsounds of her pet snails’ radulae recorded while they were eatinga carrot. The snails were Mesodon zaletus.• Charlie Sturm (Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh):Charlie, the current President of the American MalacologicalSociety, is organizing the 77th meeting of the societyto take place 23-38 July 2011 in Pittsburgh, PA. Be there!• Paul Callomon (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia):The mollusk collection of the ANSP is being recataloged withthe help of voice-recognizing software.• Paula Mikkelsen (Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca):Paula presented an overview of the history of publish-

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 21ing in malacology. In 1959, 485 papers containing the word“mollus*” were published, while in 2009 their number hadgone up to 2058.• Tim Pearce (Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh):Tim presented his ideas on the evolution of slugs fromsnails. He is trying to answer the question, “Why is it good tobe a semi-slug?”• Lynn Dorwaldt (Wagner Free Institute of Science, Philadelphia):History of the Wagner Free Institute of Science and alsothe bivalves from Isaac Lea’s collection that are kept at theInstitute. Some 19th century malacology books from the Institute’slibrary were passed around (Fig. 2).• Robert Robertson (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia):According to Gunner Thorson’s (1950) shell apextheory, protoconch morphologies reflect modes of larval development.Robert’s research shows that the theory doesn’tapply to the Pyramidellidae.• Tom Grace (Pennsylvania): New records of freshwater musselMargaritifera in the headwaters of the Schuylkill River.• Aydin Örstan (Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh):Aydin presented his developing ideas on the breathinganatomy of semi-terrestrial snails in the superfamily Rissooidea.• Bill Fenzan (Virginia): The 1 st International Cone Meetingwas in Stuttgart, Germany in October 2010. The next meetingwill be in La Rochelle, France in September 2012 (formore info see The Cone Collector: http://www.theconecollector.com/).• Makiri Sei (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia):Makiri talked about her ongoing project with Gary Rosenbergon the phylogeny of Jamaican Annulariidae based on DNAsequences.• Kevin Ripka: Kevin, a birder who recently got interested insnails, is developing an iPhone application for Northeast U.S.land snails.• Adam Baldinger (Museum of Comparative Zoology, HarvardUniversity): Adam talked about the various molluskmodels at MCZ among which are a large number of glass mollusksand other invertebrates made by Leopold and RudolfBlaschka (Fig. 3).• Megan Paustian (Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh):Megan talked about the ecology and species of theslugs in the genus Meghimatium in Japan. She also showedslides from her trip there.• Francisco Borrero (Cincinnati Museum Center):Francisco and his colleague Abraham Breure arestudying the taxonomy and biogeography of theOrthalicoidea from Colombia and adjacent areas.Fig. 2 William Wagner founded the Wagner Free Institute ofScience in Philadelphia, PA. His strong interest in conchology,along with a commitment to public lectures and free educationform a lasting legacy of the Wagner. Photo by Tom Crane.Fig. 3 Adam Baldinger described the restoration of the glassBlaschka models at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Thepelagic Argonauta argo Linnaeus, 1758, and her egg case areone of many spectacular cephalopod displays. Courtesy ofMuseum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.MAM was originally intended to travel from venue to venue, extendingthe reach and the mix of participants. If you have beenlurking and would like to consider hosting the meeting, pleaseget in touch with Liz (eshea@delmnh.org) or Leslie (lskibinski@delmnh.org) to discuss the planning process.See you next year for another Molluscan March Madness!

Page 22 Vol. 39, No. 22011 Sarasota Shell Club Award WinnersThe Sarasota Shell Club Shell Show movedto a new venue for 2011. This meant moreroom, more displays, more vendors, and ingeneral, an excellent show. Attached aresome photos of some of the winners and displays.The Sarasota Shell Club meets on thesecond Thursday of each month from Septemberthrough April. The agenda includes a programof interest to shell collectors and a shortbusiness meeting. Meetings start at 7:00 p.m.and are held at the Mote Marine Laboratory.Contact: info@sarasotashellclub.comRon Bopp, President and Awards ChairmanSarasota Shell ClubSandy Pillow presents the COA Award to Jeanette Tyson andEd Schuller for their presentation, “Mystery of the MigratingMollusk.”Mote Gold Trophy: Martin Tremor & Conrad Forlor, “Helmetsand the Bonnets of it all”COA Trophy: Jeannette Tyson & Ed Schuller, “Mystery of theMigrating Mollusk.”DuPont Trophy: Martin Tremor & Conrad Forlor, “Beholdthe Lovely Abalone.”The Hertweck Fossil Trophy went to Ron Bopp (SSC member)for “Sagittal Sections of Fossil Shells.”

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 23Best Self-collected Exhibit Trophy: James & Bobby Cordy,“Shells of Eleuthera.”Fossil Shell of the Show: Dale Stream, Siphocypraea griffini.Best of Art with Shell Motif Trophy: Charles Barr, “Big Eye”photograph.Fran Schlusemann Best of Member’s Art Trophy: CarolynMadden, “Single Valentine.”Images not available for Sarasota Shell Club Members Trophy:Lynn Gaulin, “North & South American Epitoniums”and Best Small Scientific Exhibit Trophy: Lynn Gaulin (SSCMember), “North & South American Epitoniums.”June Bailey Best of Shell Art Trophy presented by Sandy Pillowto Carl Hichman (SSC Member) for “Bridal Bouquet.”

Page 24 Vol. 39, No. 22011 Broward Shell ShowNancy GaldoThe 2011 Broward ShellShow was one of the BrowardShell Club’s best ever... a recordbreaking show! Our membershipincreased by 1/3 and attendancewas up this year with regularsand South Florida residents alike.There were many new newcomerswho discovered the wonder ofshells for the first time. Theshow’s success can be credited tothe incredible effort put forth by the entire Broward Shell Clubmembership. Thanks to each person who contributed their time,effort, and donations. The exhibitors, dealers in attendance,Broward club members, and volunteers make this event possible.SHELL SHOW AWARDS--Scientific--AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY: Sheila L.Nugent, “Gulf of Maine/Bay of Fundy EcoRegion”CONCHOLOGISTS OF AMERICA: Norman Terry, “It’s A SmallSmall World”THE DUPONT TROPHY: Harry Berryman, “FamilyCostellariidae”BEST FLORIDA/CARIBBEAN EXHIBIT: Bob Pace, “29 Speciesof Marine & Land Shells Found In About 45 Minutes”NEIL HEPLER MEMORIAL TROPHY FOR EDUCATIONALEXCELLENCE: Carole Marshall, “Gods, Goddesses,Shells and Money”BETTY HAMANN FOSSIL AWARD: Valentino Leidi, “SouthFlorida Fossils”LEN HILL MEMORIAL AWARD FOR MOST BEAUTIFULEXHIBIT: Norman Terry, “It’s A Small Small World”BEST OF THE BEST: Gene Everson, “Seashells of the NewMillennium 2000-2009 - Self-Collected”SHELL OF SHOW (self-collected): Bob Pace, Bursa grayanaSHELL OF SHOW (any manner): Sonny Ogden, Tridacna gigasBEST STUDENT EXHIBITOR: Valentino Leidi, “South FloridaFossils”PEOPLE’S CHOICE AWARD – SCIENTIFIC: Jonathan Galka,“Fossil Mollusks of South Florida”BEST BEGINNING EXHIBITOR – SCIENTIFIC: Sonny Ogden,Tridacna gigasSTUDENT (grades K through 6, any manner): Katherine Albert,“Fossilized Turban Shell”STUDENT (grades 7 through 12, any manner): Valentino Leidi,“South Florida Fossils”ONE REGION (self-collected): Bob Pace, “29 Species of Marine& Land Shells Found In About 45 Minutes”ONE REGION (any manner): Sheila L. Nugent, “Gulf of Maine/Bay of Fundy EcoRegion”ONE FAMILY (MAJOR, any manner): Kenneth Brown, “Samplingof Family Cypraeidae”The 46th annual Broward Shell Club Shell Show was held at theEmma Lou Olson Center, in Pompano Beach, Florida. This is alsowhere the club holds its monthly meetings on the second Wednesdayof each month at 6:45 p.m. Annual dues are $18 for an individualor family, $5 for a student (up to high school), and $20international.ONE FAMILY (MINOR, any manner): Harry Berryman, “FamilyCostellariidae”ONE SPECIES (any manner): Blue - Sheila L. Nugent, NucellalapillusRed - Ken Curry, Sr., “See the many faces of Scaphellajunonia”SINGLE SHELL WORLDWIDE (self-collected): Blue - SonnyOgden, Tridacna gigasRed – Gene Everson, Conus gauguiniSINGLE SHELL WORLDWIDE (any manner): Blue - GeneEverson, Eupleura volkesorumRed - James Cordy - NodipectenSINGLE SHELL - FLORIDA CARIBBEAN (self-collected):Blue - James CordyRed – Bob Pace, Bursa grayanaWhite – Amy Tripp, Arcinella cornutaJudge’s Special Merit Ribbon & White: Hugh Andison,albino horse conchFOSSILS (any manner): Blue – Harry Berryman, Placanticersaplacenta (fossil ammonoid)Red – Jonathan Galka – Fossil Mollusks of South FloridaLAND or FRESH WATER SHELLS (any manner): Judge’sSpecial Merit Ribbon & Blue - Harry G. Lee, “TerrestrialPulmonata”EDUCATIONAL: Blue – Carole Marshall, “Gods, Goddesses,Shells & Money”--Artistic--BEST BEGINNING EXHIBITOR (artistic): Jo-Ann Connolly,mirror wreath

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 25--Hobbyist--STUDENT (Grades K – 6): Blue - Katherine Albert, “SimplyParadise”MIRROR: Blue - Jo-Ann ConnollyRed - Jo-Ann ConnollyDÉCOR – TABLETOP ONLY: Red - “Shell Encrusted Head”PHOTOGRAPHY: Judge’s Special Merit Ribbon & Blue - KevanSunderland, “Willet with Melongena”Red - Sheila L. NugentWhite - Anne DupontJEWELRY and PERSONAL ACCESSORIES: Blue - Sue Burns& Mario PirasRed - Elaine AlvoNOVELTIES: Blue - Bob Pace, “Animal Caricatures”Red - Elaine Alvo, “The Collector”SPECIAL: Blue - Sue Burns & Mario PirasNorman Terry won the COA Award as well as the Len HillMemorial Award (for most beautiful exhibit) for his exhibit,“It’s a Small Small World.”BEST STUDENT EXHIBITOR (artistic, made by exhibitor):Katherine Albert, “Simply Paradise”BEST IN SHOW – HOBBYIST (made by exhibitor): Bob Pace(novelties category), “Animal Caricatures”BEST IN SHOW – PROFESSIONAL (made by exhibitor): JaeKellogg, flower arrangement on driftwoodBEST IN SHOW – SAILOR’S VALENTINE (any manner):Brandy LlewellynFAY MUCHA MEMORIAL TROPHY BEST COLLECTIBLES(any manner): Linda Zylman Holzinger, hand carvedantique pearl oyster in olivewood frame from JerusalemPEOPLE’S CHOICE AWARD - ARTISTIC DIVISION: BrandyLlewellyn, “Sailor’s Valentine”--Professional--FLOWER ARRANGEMENT (6” or less, tabletop): Blue -Brandy LlewellynFLOWER ARRANGEMENTS (greater than 6,” tabletop):Judge’s Special Merit Ribbon & Blue - Jae KelloggSAILOR’S VALENTINE (single, tabletop): Blue - BrandyLlewellynMIRROR (wall hung): Blue - Heather StrawbridgeSHELL TABLES or TRAYS: Blue - Jon OgdenDÉCOR (wall hung): Red -Heather StrawbridgeDÉCOR (tabletop): Blue - Heather Strawbridge--Collectibles--Blue – Linda Zylman Holzinger, hand carved antique pearl oysterin olivewood frame from JerusalemRed – Heather Strawbridge, Princess Charming purse collectionRed – Richard Sedlak & Michael Hickman, NautilusrepresentationsSt. Petersburg Shell Club Shell ShowThe 64th Annual Shell Show of the St.Petersburg Shell Club was held in Seminole,Florida, on 26-27 February 2011.As usual there were a great numberof crowd-pleasing shell displays. TheSt. Pete Shell Club was formed over70 years ago and meets on the secondFriday of each month (except Marchwhen it is the third Friday) at 7:00p.m. at the Seminole Rec Center, 9100113th Street, North Seminole, FL. The meetings provide a venueto share knowledge and keep updated on the latest in the worldof malaclogy. Throughout the year the club sponsores field trips,picnics, and an annual dinner. The club newsletter Tidelines ispublished quarterly and is available online. For more information: www.stpeteshellclub.org.Martin Tremor Jr. (left) and Conrad Forler (right) won theCOA Award for their exhibit “Behold the Lovely Abalone: Abaloneof the West Coast of North America and Mexico.”

Page 26 Vol. 39, No. 2October 2010 British Shell Collectors’ Club Shell ShowThe British Shell Collectors’ Club wasfounded in 1972 and held its first exhibition in1976. The 2010 show was a rousing successwith lots of great shells in both scientific andartistic displays. A listing of award winnersincludes:One Species1st Koen Fraussen: Neobuccinum eatoni (won Peter Oliver Cup)2nd Kevin Brown: Trachycardium isocardiaOne Genus/Family1st Mick Davies: British Buccinidae (won the Scotia Shield)British1st Graham Saunders: “Nomad Gene Pool”2nd Dave Rolfe: “Variation in the Common Limpet”Foreign2nd Graham Saunders: “Signature Species”Self-Made Shell Art1st Selina Wilkins: Shell Flowers (won the COA award)2nd Lucy Pitts/Loretta Spridgeon: Shell MontagesShell Photography (member ballot)1st Paul Wilkins: Ensis americanus2nd Sara Cannizzaro: “Shellfish”Shellomania1st Dave Rolfe: “A Mystery”2nd Carl and Craig Ruscoe: “Back to Front Shells” (included WalterKaro Award winning sinistral Trichia hispida)3rd Angela Marsland: Self-collected Florida FossilsJunior: age 12 - 161st Theo Tamblyn: Unionid mussels (won John Fisher Trophy)Junior: 11 & under1st Christopher Wilkins: Moving MolluscsDealer Shell of the Day (member ballot)1st Fernand de Donder & Rika Goethaels: Nodipecten magnificusShell of the Show1st Carl & Craig Ruscoe: sinistral Trichia hispida (Linnaeus, 1758)British Shell Collectors’ Club President Derek Howlett presentsthe COA Award to Selina Wilkins for her shell art exhibittitled “Shell Flowers.”Above: Carl Ruscoe holds the Walter Karo Award for Shell ofthe Show, a sinistral Trochulus hispidus (Linnaeus, 1758) thehairy helicellid. This small land snail (7.9mm) was collected inflood debris by the River Ribble, at Samlesbury, near Preston,Lancashire, England, by Carl and Craig Ruscoe. Often listedas Trichia hispida, a junior generic homonym that was disallowedby the ICZN (see H. Lee comments and an image of thisshell at: http://www.jaxshells.org/dr29s.htmLeft: These shell montages by Lucy Pitts and Loretta Spridgeontook second place in the ‘Self-Made Shell Art’ category.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 27Oregon Society of ConchologistsShell ShowThe Oregon Society ofConchologists Shell Showwas held 26-30 April 2011in the main viewing areaof the Oregon Museum ofScience and Industry inPortland. Total attendanceat the museum over thesedates was 17,168 and estimates by museum staff are that at least90% visited the shell exhibit. John Mellott was show chair, and itwas a most successful shell show. The COA Award was won byJudy Barrick with an exhibit titled “Latiaxis Shells.” Judy had35 species of Coralliophilinae on display in six feet of cabinets.She also took “Best Single Shell” of the show with a specimen ofBabelomurex yumimarumai Kosuge, 1985. Other major awardswere: the DuPont Award to Jonathan Reid for his exhibit “Cowriesof the World,” and the Jean McCluskey Award (most educationaldisplay) to Judy Barrick (she really had quite a display) for “LatiaxisShells.”The Oregon Society of Conchologists is a non-profitorganization founded in 1965. Monthly meetings are held at variouslocalities throughout northwestern Oregon. Membership isover 70 and varies from beginners to professionals. Club Presidentis Joyce Matthys; information at: www.oregonshellclub.com.What is a shell worth?Hi Tom,As editor, for many years (23 editions), of A Catalog of Dealers’Prices for Shells, I have often been asked, “What is thehighest price ever paid for a single shell?” I have never beenable to feel confident in a reply to this question, however, Ihave reliable information that a Bangkok collector recently(December 2010) paid $45,000 (U.S.) for a sinistral specimenof Turbinella pyrum (Linnaeus, 1758).I also heard of an offer of 30,000 Euros (made this year) for aspecimen of a very rare Cypraeidae, Nesiocypraea alexhubertiLorenz & Hubert, 2000 (now placed in the genus Austrasiatica).The offer was apparently rejected by the owner of thespecimen.Tom RiceRawai Beach, Phuket, ThailandJudy Barrick wins the COA Award with “Latiaxis Shells.” Herdisplay featured 35 species of these often intricately sculpturedshells, now considered a subfamily of Muricidae.Three Turbinella pyrum or sacred chank shells that havebeen intricately carved for possible use in religious ceremonies(image courtesy of Wikipedia.com). These are commonright-handed or dextral specimens and are not nearlyas rare as left-handed or sinistral specimens. The sacredchank was discussed by Jesse Todd in his article “Conchshells on coins,” American Conchologist, vol. 39, no. 1(March 2011). For more information about a rare sinistralspecimen, see Harry Lee’s article “Historical notes ona sinistral sacred chank: Turbinella pyrum,” in this issue.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 29How and when Maxwell Smith obtained his Calvert materialis unknown to me, but labels (possibly other archival materials)in the FLMNH may hold some clues. Smith’s collection wentto the University of Alabama, which institution was so grateful itrewarded its benefactor with a D. Sci. (Abbott, 1973)! Regrettablythe university later felt it was unable to maintain the collection andit was ceded to the FLMNH in the mid-1980’s and placed in FredG. Thompson’s stewardship.Hindu priest blowing a “trumpet” made out of a large chankshell - Turbinella pyrum. Shells used in this manner are oftenintricately carved and heavily decorated with brass and silver.Image from Wikipedia.com.There is a long and well-studied relationship betweenHindu scripture (and folklore) related to Turbinella pyrum and, inparticular, the sinistral mutant. This unique chapter in “ethnoconchology”is nicely summarized by Rose (1974). It is written thatVishnu, or one of his avatars, hid sacred liturgical scrolls insidea sinistral chank. While there are great numbers of shell collectors(and postage stamp printers) who cannot distinguish a sinistralfrom a dextral snail shell, a good Hindu knows the difference! Aconsequence of this unusual familiarity and affinity is a demandfor ownership which amplifies the market value beyond Westernconchological benchmarks. Thus, there are probably hundredsof these specimens in Indian households and, to the best of myknowledge, only three in American shell collections!Beyond the scriptural chronicle above, I believe that theoften-trivialized act of (a human) decanting the liquid contentsof a sinistral shell (seldom available in T. pyrum; characteristicin Busycon perversum sinistrum Hollister, 1958) using his righthand (vs. the opposite set-up) reinforces the virtue of the sinistralchank and may be intertwined with the scriptural and liturgicalHinduism. This simple act is ceremonial in many religions andimplications of right and left hand usage are even more widelyappreciated, conspicuously in India. Demand for B. perversumshells in that country is astoundingly high vs. the conchologicalvalue we Westerners attach to this common species.Rarely do we get a numerical handle on the frequency ofreversal of gastropod coil, but owing to the economic importanceof the chank fishery in southern India, the British Colonial Governmentkept scrupulous records. It turned out that only 1 shell in600,000 was left-handed (Hornell, 1916). Compare that with 1:283(Busycotypus canaliculatus embryos: Lee, ), 1:440 (Prunum apicinum: Lee, 1979), 1:760(Hyalina philippinarum: Coovert and Lee, 1989), and ~1:100,000(Cerion species: Lee, 2011).The infrequency of sinistral sacred chanks alone warrantsa certain status in the pantheon of rare natural history objects, butthe added mystique may be what is needed to make this the mostsought after of all shells.Priceless, however, is holding such an object, howevertemporarily, and knowing it has a chain of ownership reachingback to at least Victorian Era (ig)Nobility and reflecting on theassortment of characters who shepherded it to its ultimate repose,intended to be the FLMNH.Abbott, R.T. [ed.], 1973. American Malacologists: A national register ofprofessional and amateur malacologists and private shell collectors andbiographies of early American mollusk workers born between 1618 and1900. American Malacologists, Falls Church, VA. 1-494 + iv.Coovert, G.A. and H.G. Lee, 1989. A review of sinistrality in the familyMarginellidae. Marginella Marginalia 6(1-2): 1-15. Jan.-Feb.D’Attilio, A., 1950. Some notes on the great Calvert shell collection.New York Shell Club Notes 2: 2-3 [reprinted in 1974 in New York ShellClub Notes 200: 5-6].Dance, S.P., 1986. “A history of shell collecting.” E.J. Brill - Dr. W.Backhuys, Leiden. Pp. 1-265 + xv + 32 pls.Hornell, J. 1916. The Indian varieties and races of the genus Turbinella.Memoirs of the Indian Museum. 6:109-125, 3 pls.Lee, H.G., 1979. Letters to the editor [on sinistral marginellids]. TheMollusk 17:(1): 2. Jan.Lee, H.G., “2010” [2011]. Gettleman key to probe of majorreversals. American Conchologist 38(4): 6-11. “Dec.” [Jan.].Rose, K. 1974. The religious use of Turbinella pyrum (Linnaeus), theIndian Chank. The Nautilus 88(1):1-5. Jan.Harry G. Lee - shells@hglee.com

Page 30 Vol. 39, No. 2SCUM XV: Southern California Unified MalacologistsLindsey T. GrovesStanding (l to r): Lindsey Groves, Ananda Ranasinghe, Scott Rugh, James Jacob, James McLean, Kelvin Barwick, Ángel Valdés,Shawn Weidrick, Bill Tatham, Jessica Goodhart, Rich Nye, Dieta Hanson, Bob Dees, John Ljubenkov, Jillian Walker, DonCadien.Kneeling (l to r): Joanne Linnenbrink, Zoe Allen, Lance Gilbertson, Jackson Lam, Pat LaFollette, Bob Moore.Present at SCUM XV but not in photo: James Preston Allen, Doug Eernisse, Suzanne Matsumiya. (Image by Doug Eernissewith the author’s camera)The 15 th annual gathering of Southern CaliforniaUnified Malacologists (SCUM) was held at the headquartersof the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project(SCCWRP), Costa Mesa, CA. Twenty-five professional, amateur,and student malacologists and paleontologists attended the eventon Saturday, March 5 th , 2011. An unanticipated local poweroutage at scheduling time forced a later than usual gatheringthis year. This informal group continues to meet on an annualbasis to facilitate contact and keep members informed of researchactivities and opportunities. In keeping these gatherings informal,there are no dues, officers, or publications. It is hoped that thecontinuing success of informal groups such as SCUM, Bay AreaMalacologists (BAM), Mid-Atlantic Malacologists (MAM),Ohio Valley Unified Malacologists (OVUM), and FUM (FloridaUnified Malacologists) will encourage more regional groups ofmalacologists and paleontologists to meet in a likewise manner.SCUM XV host Kelvin Barwick welcomed the groupand in SCUM tradition all present were given the opportunity tointroduce themselves and give a short update about current molluskrelated activities and interests. Most presentations were informalbut several were more detailed. John Ljubenkov presented aninteresting program on hydroids that attach to mollusk shells,many of which are deep water species (ie., Halitholus cirratus onthe deep water bivalve Acila castrensis). Most hydroids seem toprefer appear attachment to dead mollusk shells rather than livingshells. Jessica Goodhart, Jillian Walker, Jackson Lam, and DietaHanson, who work with Ángel Valdés at Cal Poly Pomona, madepresentations on their research. As always, in addition to his busyteaching schedule, Doug Eernisse (Calif. St. Univ. Fullerton)updated everyone on his extensive research projects with hiscolleagues and grad students. Pat LaFollette presented an updateon pyramidellid literature acquisitions via internet resources. ScottRugh presented research on comparisons of modern environmentsto those of the late Pliocene San Diego Formation environments.Numerous discussions and comments resulted from thesepresentations. SCUM XVI will be hosted by John Ljubenkov atthe Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, San Pedro, CA, in January of 2012.SCUM XV participants and their respective interests and/oractivities:James Preston Allen (San Pedro, CA): Attending SCUM XVwith daughter Zoe Allen and publisher of Random Lengths, anindependent newspaper in San Pedro, CA.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 31Zoe Allen: High school student and volunteer at the CabrilloMarine Aquarium, San Pedro, CA.Kelvin Barwick (Orange Co. Sanitation District): Continuesresearch on mollusk and polychaete faunas of the SouthernCalifornia Bight and current Treasurer of the Western Society ofMalacologists.Don Cadien (L.A. Co. Sanitation District): Currently researchingenvironmental biology of bathyal and abyssal invertebrates ofsouthern California.Bob Dees (San Diego Shell Club): Former President of OrangeCoast College but continues to collect shells and is current Vice-President of the SDSC.Doug Eernisse (Calif. St. Univ. Fullerton): In addition to teachingduties Doug has a myriad of research projects with professionaland grad student colleagues including: Phylogenetics and affinitiesof Fissurella volcano; Ostrea phylogeny and phylogeographyin the Gulf of California; new species of brooding chitons fromSanta Catalina Id., California Channel Islands; DNA bar-coding ofIndonesian chitons; research on new species of the sea star genusHenricia; and shield limpet habitat analysis.Lance Gilbertson (Newport Beach, CA): Research Associate atthe Nat. His. Mus. L.A. Co. continues with research on terrestrialmollusks of the southwest.Jessica Goodhart (Cal. Poly. Pomona): Researching life cycleand development of Haminoea vesicula and comparison to theinvasive species H. japonica in California.Lindsey Groves (Nat. Hist. Mus L.A. Co.): Continues asCollection Manager at NHMLAC. Has recently published a paperwith descriptions of 11 new cypraeid species from the CantaureFormation of northern Venezuela and has a paper in press on newcypraeoideans from the Paleogene of Washington, California, andBaja California Sur, Mexico.Dieta Hanson (Cal. Poly. Pomona): Researching Haminoeajaponica and its affects on the native cephalaspidean species inSan Francisco Bay and its phylogeny.James Jacobs (College of Borrego, Borrego Springs, CA):Interested in fossil faunas of the area.Pat LaFollette (Nat. Hist. Mus. L.A. Co.): Continues rearrangingthe Pyramidellidae in the NHMLAC malacology collection andcontinues to acquire pertinent pyramidellid literature via theinternet. More recently has collected numerous micro-gastropodsfrom Miocene deposits in the San Gregorio Pass area, RiversideCounty, many of which may be undescribed species.Jackson Lam (Cal. Poly. Pomona): Researching deep-sea Arminanudibranchs many from expeditions to New Caledonia by theParis Museum, particularly their reproductive systems, jaws, andradulae. Presented a short video exhibiting a strange feedingbehavior in Armina.Joanne Linnenbrink (Cal. St. Univ., Long Beach): Currentlyan undergraduate student preparing to attend Calif. St. Univ.,Fullerton, and work with Doug Eernisse.John Ljubenkov (Pauma Valley, CA): Self proclaimed “industrialtaxonomist.” Currently studying hydroids that grow on living anddead mollusk shells in deep and shallow water.James McLean (Nat. Hist. Mus. L.A. Co.): Jim continues workon his eagerly anticipated volumes on North Pacific shelledgastropods. His monograph of worldwide Liotiidae is nearlycomplete.Suzanne Matsumiya (San Pedro, CA): Attending SCUM XVwith daughter Zoe Allen.Bob Moore (Nat. Hist. Mus. L.A. Co.): Volunteer at NHMLACand avid shell collector who is currently curating material collectedby urator Emeritus James McLean in South Africa.Rick Nye (Calif. St. Univ., Fullerton): Researching the limpetLottia scabra and its distribution in northern California versusthat in southern California, particularly near Pt. Conception, SantaBarbara County, a natural faunal barrier.Ananda Ranasinghe (SCCWRP): Because he volunteered toallow access to the meeting facility on a day off, Ananda was madean honorary SCUM member.Scott Rugh (Escondido, CA): Currently doing contract work withthe US Geological Survey making a comparison of modern offshorefaunas to those of the late Pliocene San Diego Formation.Bill Tatham (Pacific Conchological Club): First-time SCUMattendee with an interest in Conidae.Ángel Valdés (Cal. Poly. Pomona): Teaches Evolutionary Biologyand continues phylogenetic research on opisthobranch gastropodsof the Caribbean and Panamic provinces.Jillian Walker (Cal. Poly. Pomona): Researching Aplysia insouthern California and its reproductive strategies.Shawn Wiedrick (Pacific Conchological Club): Current Presidentof the PCC and interested in all areas of shell collecting. Volunteersat the Nat. Hist. Mus. of L.A. Co. identifying micro-turrids of theIndo-Pacific.Lindsey T. GrovesNatural History Museum of Los Angeles CountyMalacology Section900 Exposition Blvd.Los Angeles, CA 90007lgroves@nhm.org

Page 32 Vol. 39, No. 2Interesting boringHe Jingspecimens. I am unable to present any scientific conclusion inthis short article, but I hope to offer some interesting examples ofshells that have suffered boring attacks.Struggle for lifeWhen I observe shells with indications of boring, theyseem to provide a capsule documentary that vividly presents thebrutal struggle for survival by our colorful creatures of the sea.Many shells have incomplete borings and many have multiple borings.I found a cone with four borings, none of them completed.Fig. 1 A bivalve shell with a bored hole.IntroductionI often recall the days when I started shell collecting, overtwo decades ago. One of the scenes that often plays back in mymemory is the first time I picked up a bivalve shell on the seashoreand found a hole on it. My curiosity drove me to find its cause.Fortunately there was an easy answer; the hole is left after a predatordrilled into the shell. The boring differs a lot from the smallerpinholes caused by an octopus or the chipping caused by fish andcrabs. The hole bored into a shell is a regular circle. It is neat andbeveled, with chamfered edges.After I started working as a professional shell dealer Ihad the chance to visually inspect and handle a great number ofunsorted shells. I began setting aside shells with boring marksand quickly had a great many such shells. I thought other collectorsmight be interested, as many collectors do not get to examineshells before a dealer has sorted them and culled the “unsightly”Fig. 3 A cone with four borings.Fig. 2 A Turbo chrysostomus showing several boring attempts.Why so many borings in a single shell? Apparently thecone was doing its best to escape while at the same time the predatorrefused to give up easily. The repeated attacking and defenseresulted in the multi-borings.Is there any chance that more than one predator drilled inthe same time? I believe the answer is yes. I had an olive specimenthat had two completed holes bored into the shell. If thesewere bored by the same predator, why would it drill the secondhole after succeeding with the first? One assumption could be thatthe olive escaped just after the predator completed the first hole,leaving it no time to enjoy the result of its labor. The predator thenhad to do it again. This assumption leads to another question. Ifboth borings were from the same attacker, why not search out anduse the finished hole for the second attack - unless it was placedincorrectly. Or the predator may not remember where it drilled for

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 33its first attempt. It is certain that no conclusion can be reached byjust looking at the end result on a shell - as interesting as it mightbe.Fig.4 An olive specimen with 2 completed borings.Nevertheless, the specimens I have gathered clearly showthat life in the sea is tough. The drilled shells either lose their livesor fight tenaciously and live with scars. As for the predators, theycertainly do not seem assured of victory with each attack.How to drill?A number of books discuss the mechanics involved indrilling into a shell. First, the predator gets control of the prey,then secretes a variety of chemicals called carbonic anhydrases.The drilling lasts a few hours to several days. I have not done astudy of the chemicals involved or the duration of the boring process.From the specimens I have collected, however, it seems thatthe predator does not always have a good control of its intendedprey. Some of the prey are quite large in comparison to smallerpredators. It would seem there is no control by the predator insuch situations, but rather a smaller Murex or Natica just “hangson” while boring through the victim’s shell. Another interestingphenomenon is the position of the boring. It seems the position isnot decided by the predator, instead, it is more likely determinedby the shape of the prey’s shell.Fig 5 b A large fasciolarid specimen with borings on the spire.The drilling position among certain prey species is almost identical.This may indicate a vulnerable spot on the shell or just themost available area for an attack.Fig. 6 A group of olives showing that in all but one case, thesame point of attack was used.Fig.7 A group of turbans with drill attempts.Fig 5 a A large turban specimens with borings. Note the serationsaround the perimeter of the boring.The boring position of gastropod shells is typically justbehind the aperture on the ventral surface of the shell, about onewhorl in from the outer lip. This position is probably where theanimal inside the shell is accessible and thus vulnerable. A holedrilled on the dorsal surface would likely find an empty shell as theinhabitant can withdraw deeper into the shell. This ventral drillingposition is quite close to the aperture of the victim, indicating

Page 34 Vol. 39, No. 2little threat from the prey animal (biting or other self-defense actions).In contrast, I found that bivalve shells are usually attackedand drilled at the rear portion of the shell near the hinge, but eventhis is variable and the images I have provided show borings intobivalve shells in many different areas.Fig.8 Borings near the hinge on bivalves.Fig.10 A boring worksite amidst barnacles on a murex.easily broken. They are drilled into in much the same way as theirthicker-shelled neighbors.Some tiny shells also show signs of being bored into,maybe indicating even smaller attackers.Fig.9 Borings on the thick spire section of strombids.Not all drill holes are found in the same area of a givenspecies. Architectonicid shells seem to be attacked on both thedorsal (most often) and ventral surfaces. It looks like the predatormay not know where it should attack. The illustrated example(Fig. 12) shows a shell with the drill hole in the apex.The thickness of the shell area portion does not seem tobe a deterrent to drilling as predators seem to focus more on theaccessibility of the prey’s flesh after the shell is bored open. Thismay explain why cones and strombs frequently show boreholes atthe thickened shoulder area.I have a murex specimen which is densely covered bybarnacles (Balanidae). Apparently the barnacles around the boringposition were cleared by the predator to enable it to have enoughroom to start its bore hole. I have no idea how the predator clearedthe barnacles or why it prepared such a spacious site, an area seeminglymuch larger than needed to bore into the shell.With shells like turbans with their thick shells and opercula,it is quite understandable that attackers dominate them bydrilling. They seem well protected against others avenues of attack.Yet many victims with bore holes have thin shells, seeminglyFig.11 Micro shells (size between 1mm to 4mm) also showsigns of boring attacks.Boring attacks also happen in the deep sea. I have collectedmany shells from the East China Sea at 100+ meters withindications of boring attacks.Most literature lists muricids and naticids as predators,but in fact they are often victims and often show evidence of boringattacks. I have collected many other shells with evidence ofboring attacks, but have yet to find a specimen of cephalopod

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 35Fig.12 Borings on various specimens from deep water.Fig. 15 Borings on Scaphopoda shells.Fig.13 Naticidae shells with borings.Fig. 16 Borings at Bivalvia shellsFig.14 Muricidae shells with borings.or chiton with evidence of bore-holes. It is certain that gastropods,bivalves, and scaphopods are vulnerable.The thing that puzzles me most is that I have never founda single cowrie with a bore-hole. I have handled thousands of Cypraeamiliaris and Cypraea hungerfordi, and inspected them oneby one. In 2007 during my journey to Hainan Island I asked workersof a shellcraft workshop to check a batch of Cypraea moneta,the weight of which approached one ton. None was found withany evidence of a boring attack. I also asked fishermen to collectcowries with bore holes for me, but what eventually turned upwere small pinholes, not borings. My search will continue.He Jingwww.shellsfromchina.com

Page 36 Vol. 39, No. 2Fig.17 Various gastropods with evidence of boring attacks.

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 37Mattheus Marinus Schepman (1847-1919)and His Contributions to Malacologyby A.N. Van Der Bijl, R.G. Moolenbeek,and J. Gould2010, Netherlands Malacological Society,Leiden, 200 pages, ISBN 978-90-815230-11, $50 at anvdbijl@xs4all.nlAs early as the 1500s, shell collectors inthe Netherlands were at the vanguard of a growinginterest in natural history fueled by the wondersbrought back from expeditions around the world.Dutch interest in conchology continues today, asevidenced by shell publications and the NederlandseMalacologische Vereniging [NetherlandsMalacological Society]. This society was begunin 1934 and in celebration of its 75th anniversary,a special book was published in honor of andabout Mattheus Marinus Schepman, one of, if notthe most, important shell collectors of his countryand certainly one of the top collectors in Europe.M. Schepman combined the fascination andwonder of shells as objects of natural history witha scientific approach that made his collection ofgreat value to the entire malacological community.Schepman amassed an extensive shell collectionby self-collecting, trade, and purchase. Moreimportantly, he was selected by M.W.C. Weber,Director of the Zoölogisch Museum Amsterdam(ZMA), to identify and describe the malacologicalspecimens collected during the Siboga Expedition(1899-1900). This expedition collected flora andfauna samples from 322 sites among islands in theIndo-Malaysian Archipelago. Mollusks from a previous similarexpedition had been identified by K.E. Von Martens, who probablyrecommended Schepman for the work on the second expedition.From 1908 to 1913, Schepman published descriptions in sevenvolumes of some 1,235 species of shelled mollusk, many new toscience. All totaled, he identified over 2,500 mollusk specimens.This work established Schepman’s credentials as a conchologist.He continued to aggressively build his private collection and afterhis death the Schepman collection was purchased in 1920 by theZoölogisch Museum Amsterdam (University of Amsterdm, Amsterdam,the Netherlands). For ƒ6,205, the museum obtained acollection of shelled marine, freshwater, and land mollusks totalingapproximately 9,000 species in 1250 genera. Also includedwere 10 large oak cabinets and an extensive library.This present work provides a quick review of Schepman’slife, and then adds texture, color, and interest, by including:transcripts and images of letters to and from dealers and otherwell-known shell collectors, images of his collection and dataslips, images of his contemporary malacologists, and a completebibliography (he wrote over 60 malacological publications). Thisis followed by a lengthy section on “New Taxa Introduced by MattheusMarinus Schepman.” Here the authors have provided descriptionsand superbly detailed illustrations (many published forthe first time) of some 450 taxa introduced by Schepman. Whenthere is no illustration, it is because the described specimen is fromthe Siboga Expedition, and all 32 plates from this expedition areincluded in a later chapter. Thus every taxon is illustrated. Justhaving available this treasure trove of type illustrations is of greatvalue, but the authors have gone further by listing type localitiesand by providing a detailed analysis of questionable type status.The authors also provide a listing of taxa named after Schepman,taxa he named after other persons (including etymologies), andseparate listings of the Schepman taxa sorted alphabetically byfamily (and then species), by genus (and then species), and bycomplete name (family, genus, species, subspecies).This is a well-researched, well-written, and richly illustratedaddition to conchological literature. It is not intended forthe casual shell collector, but it provides a needed window into animportant part of conchological (or malacological) history as wellas a needed reference tool. For anyone who aspires to a more detailedknowledge of shelled mollusks, this book is a most welcomeaddition.Tom Eichhorstthomas@nerite.com

Page 38 Vol. 39, No. 2Compendium of Florida FossilShells Volume 1Middle Miocene to Late PleistoceneMarine Gastropodsby Edward J. Petuch & Mardie Drolshagen2011, MdM Publishing, Wellington, FL, DVD inslim plastic “jewel case” - $19.95 from Mal de MerBooks, MDMSHELLBOOKS.COMThis is an intriguing concept of a DVD combined witha hard copy book version to be published at a later date. Thereare pluses and minus to both media, so hopefully this combinationwill allow readers to benefit from the pluses of each. Thisis a planned series of six volumes on fossil shells of Florida byEdward J. Petuch and Mardie Drolshagen, who earlier combinedtheir talents on “Molluscan Paleontology of the Chesapeake Miocene.”Dr. Edward Petuch of Florida Atlantic University providesthe fossil expertise while Mardie Drolshagen of Black DiamondPhotography provides meticulous and detailed photographs of thetaxa being discussed as well as some interesting Florida scenery.The planned six volumes are divided by ‘stratigraphicimportance,’ with volumes one to four covering the more important(stratigraphically characteristic) and abundant marine gastropodfossils, while the last two volumes cover marine and freshwatergastropod fossils more rarely encountered as well as bivalvefossils. Over the course of the planned publications, more than400 gastropod and bivalve genera will be described and illustrated.This includes more than 300 new species and 20 new genera.Florida has become rather well known for its rich fossilassemblages with over 1,500 molluscan fossil species (over 5mmin length) having been discovered to date. The 1994 publicationof the “Atlas of Florida Fossils Shells” by Edward Petuch has beensomewhat overcome by the discovery of hundreds of new species.The planned six volume publication should do much to resolvethis issue. This first volume reviews seven gastropod families:Strombidae, Cypraeidae, Ovulidae, Eocypraeidae, Triviidae, Conidae,and Conilithidae. Also provided in some detail is a review ofFlorida geology with discussions of regional stratigraphic formations,coastal paleoceanography, and the paleoecology of NeogeneSouthern Florida.The “book” (I have not yet seen the hard copy version,but I assume it will be substantially the same as the DVD version)begins with a short general history of fossil collecting in southernFlorida and then covers specific collecting areas. Many of theseareas are now closed to public collecting, but interested fossilhunters can often work through local shell clubs to obtain access.While I am not personally familiar with these names, I am suremany fossil hunters in COA will recognize names such as: MulePen Quarry, Brantley and Cochran Pits, Rucks Pit, Griffin BrothersPit, etc. Each is analyzed for its fossil origins, richness, diversity,and originating geological formation. This introduction to the collectingareas of southern Florida is followed by a listing of the 119new species named in this volume. These and an additional 172related species are all illustrated in volume 1.All of the above is introduction. Chapter one is a detailedcoverage of the “Geologic Framework of Southern Florida,” includingspecific details about some dozen major Florida geologicformations. This is followed in chapter two by a step back in timeto the now long-gone Okeechobean Sea, the Paleocene formationthat is now the Everglades. Most recognize the defining natureof Florida’s Everglades, but here is a fascinating journey back tothe Eocene to review the geology of the area and how it came toprovide such a rich molluscan environment during the Paleocene.All of this, from the introduction onward is accompanied by photographsthat bring additional life to the text.The remaining chapters are dedicated, one or two familiesper chapter (grouped by genus), to the molluscan familiescovered in this volume. Each species is thoroughly described, illustrated,and details provided as to type measurements, location,stratigraphic range, and name etymology. The species descriptionsend with a general discussion where additional details areprovided, such as comparisons to similar species. Almost all of thephotographs are black and white, but considering the lack of colorin most fossils and the added sharpness of a B&W photograph, thisis certainly not a detracting aspect.Now back to the nature of such a publication on DVD. Athorough index is provided, but it can still take some time scrollingto the page desired. Here a book would be much handier. Onthe other hand, the images can be enlarged to show an incredibleamount of detail. Because of this, I believe amateur collectorsinterested in Florida fossils as well as professionals will undoubtedlywant both hard copy and electronic versions. Those unsure oftheir interest in this area can purchase the DVD for the relativelyinexpensive price of $19.95. If the DVD suits your needs, thenyou are done (until the next volume). If you decide you would alsolike the hard copy (there is something after all inherently “right”about a book - at least to those of us born in the previous century),the purchase of the DVD includes a coupon that entitles you to adiscount off the book price ($89.95), dropping the price to $60. Ido not know if this will be true for later volumes.Tom Eichhorstthomas@nerite.com

June 2011 American Conchologist Page 39Shells of the Hawaiian IslandsVol. 1, The Sea Shells; Vol. 2, TheLand Shellsby Mike Severns2011, Conchbooks, Hackenheim, Germany, pp. 564,pl. 225 (sea shells) & pp. 460, pl. 186, 363 maps (landshells), ISBN 978-3-939767-35-0, for both volumesin slip case: ISBN 978-3-939767-33-0; Vol. 1 approx.,$297, Vol. 2 approx., $235, both vol. in slipcase, approx., $431.Allison Kay published “Hawaiian Marine Shells” in 1979and listed 966 valid species of shelled marine mollusks in Hawaii.A lot has happened since then. The present work by Mike Severnslists 1,333 valid species of shelled mollusks in the islands and asPhilippe Bouchet states in the introduction to Severn’s work (p.31), “…there is still a long way to go to a ‘complete’ inventory ofHawaiian marine molluscs.” In the meantime, we have a superblywritten and lavishly illustrated work that is much more than an updateon Kay’s work. The color plates are 8.5 x 11.5 inches, whichmeans many of the shells are illustrated at much greater than lifesize. An 11mm specimen of Triphora earlei Kay, 1979, is shownat better than 100mm! A 4mm specimen of the Hawaiian endemicSmaragdia bryanae (Pilsbry, 1917) is shown at 55mm. These aresharp, definitive images with details of sculpture and protoconch,as well as subtleties of color pattern evident as never before. Speciesfrom streams, shallow intertidal waters, coral reef habitats,and deep water are all represented with the name, size, a quickcomment about where the specimen was collected, and a crystalclear color image. Vol. 1 also includes an introduction to the Hawaiianbiota by Philippe Bouchet. He discusses endemism and thedifficulty of any mollusk arriving at and settling in Hawaii.Vol. 2 completes this marvelous set with more detailsabout the development of the Hawaiian Islands and a history ofland snail collecting and research on the islands (by BernhardHausdorf). Recorded land snail species climbed steadily fromthe initial descriptions by Captain Cook and Captain Dixon in theearly 1800s to a known 750 species (most endemic) by the late1940s. Sadly more than 75% of the land snail species on Hawaiiare now extinct. The causes are many and fairly well-known (e.g.habitat destruction and introduction of alien species), but that doesnot bring back any of those lost species. Interestingly, the authoralmost accomplished this feat. The land snail genus Partulina wasthought by many authorities to have become extinct on Hawaii.Our author proved that not only was it not extinct, but that therewere a number of thriving populations on the different islands. Itwas literally a case of endless searches through thick rain forest,only to find the quarry in the tree under which he had been parkinghis jeep. Since then he has spent several decades documenting thisgenus and other rare land snails in Hawaii. Another interestingaspect of Hawaiian land snails: of the voucher specimens in islandmuseums, perhaps 20% are as yet undescribed!With both volumes, Mike Severns contacted authoritiesaround the world to ensure his data were correct and up-to-date.For example, the Cypraeidae section was reviewed and commentsprovided by Felix Lorenz; Mitridae by Richard Salisbury, Muricidaeby Roland Houart, etc. Our knowledge of the molluscanworld is growing daily, with hundreds of new species named eachyear and new research methods providing a better insight into thestatus of different species. Because of his meticulous preparationand research, as well as illustrations second to none, these booksare well worth the price. Yes, they are a bit expensive, but oncein hand you will realize that the excellence of the work drove theprice and that no better references can be found for Hawaiian Islandsea and land snails.Tom Eichhorst -- thomas@nerite.com