Angels - PageSuite

Angels - PageSuite

Angels - PageSuite

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

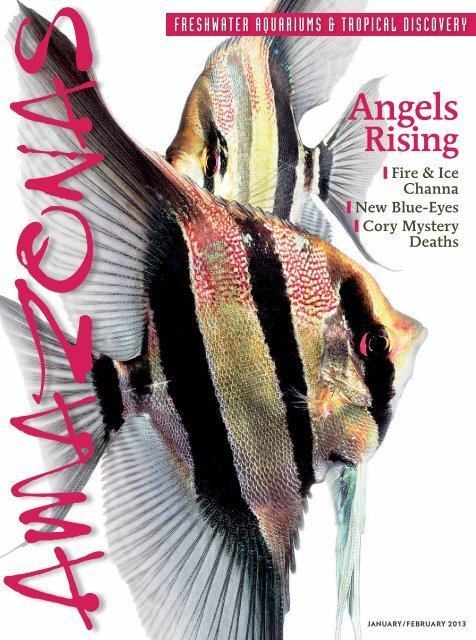

FRESHWATER AQUARIUMS & TROPICAL DISCOVERY<br />

<strong>Angels</strong><br />

Rising<br />

❙ Fire & Ice<br />

Channa<br />

❙ New Blue-Eyes<br />

❙ Cory Mystery<br />

Deaths<br />

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2013

EDITOR & PUBLISHER | James M. Lawrence<br />

INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHER | Matthias Schmidt<br />

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | Hans-Georg Evers<br />

CHIEF DESIGNER | Nick Nadolny<br />

SENIOR ADVISORY BOARD |<br />

Dr. Gerald Allen, Christopher Brightwell, Svein A.<br />

Fosså, Raymond Lucas, Dr. Paul Loiselle, Dr. John<br />

E. Randall, Julian Sprung, Jeffrey A. Turner<br />

SENIOR EDITORS |<br />

Matthew Pedersen, Mary E. Sweeney<br />

CONTRIBUTORS |<br />

Juan Miguel Artigas Azas, Dick Au, Heiko Bleher,<br />

Eric Bodrock, Jeffrey Christian, Morrell Devlin,<br />

Ian Fuller, Jay Hemdal, Neil Hepworth, Maike<br />

Wilstermann-Hildebrand, Ad Konings, Marco<br />

Tulio C. Lacerda, Michael Lo, Neale Monks, Rachel<br />

O’Leary, Martin Thaler Morte, Christian & Marie-<br />

Paulette Piednoir, Karen Randall, Mark Sabaj Perez,<br />

Ben Tan, Stephan Tanner<br />

TRANSLATOR | Mary Bailey<br />

ART DIRECTOR | Linda Provost<br />

DESIGNER | Anne Linton Elston<br />

ASSOCIATE EDITORS |<br />

Louise Watson, John Sweeney, Eamonn Sweeney<br />

EDITORIAL & BUSINESS OFFICES |<br />

Reef to Rainforest Media, LLC<br />

140 Webster Road | PO Box 490<br />

Shelburne, VT 05482<br />

Tel: 802.985.9977 | Fax: 802.497.0768<br />

BUSINESS & MARKETING DIRECTOR |<br />

Judith Billard | 802.985.9977 Ext. 3<br />

ADVERTISING SALES |<br />

James Lawrence | 802.985.9977 Ext. 7<br />

james.lawrence@reef2rainforest.com<br />

ACCOUNTS | Linda Bursell<br />

NEWSSTAND | Howard White & Associates<br />

PRINTING | Dartmouth Printing | Hanover, NH<br />

CUSTOMER SERVICE |<br />

service@amazonascustomerservice.com<br />

570.567.0424<br />

SUBSCRIPTIONS | www.amazonasmagazine.com<br />

WEB CONTENT | www.reef2rainforest.com<br />

AMAZONAS, Freshwater Aquariums & Tropical Discovery<br />

is published bimonthly in December, February, April,<br />

June, August, and October by Reef to Rainforest Media,<br />

LLC, 140 Webster Road, PO Box 490, Shelburne, VT<br />

05482. Application to mail at periodicals prices pending at<br />

Shelburne, VT and additional mailing offices. Subscription<br />

rates: U.S. $29 for one year. Canada, $41 for one year.<br />

Outside U.S. and Canada, $49 for one year.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: AMAZONAS,<br />

PO Box 361, Williamsport, PA 17703-0361<br />

ISSN 2166-3106 (Print) | ISSN 2166-3122 (Digital)<br />

AMAZONAS is a licensed edition of<br />

AMAZONAS Germany, Natur und Tier Verlag GmbH,<br />

Muenster, Germany.<br />

All rights reserved. Reproduction of any material from this<br />

issue in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.<br />

COVER:<br />

Pterophyllum altum: Wild pair<br />

from the Rio Atabapo.<br />

Photos: B. Kahl<br />

<br />

4 EDITORIAL by Hans-Georg Evers<br />

6 AQUATIC NOTEBOOK<br />

COVER STORY<br />

24 THE LATEST ON PTEROPHYLLUM:<br />

Species and forms of angelfishes<br />

by Heiko Bleher<br />

32 A LIFE WITH ANGELS<br />

by Bernd Schmitt<br />

42 PTEROPHYLLUM ALTUM:<br />

The King of the Río Orinoco<br />

by Simon Forkel<br />

48 ANGELFISH: GENETIC TRANSPARENCY<br />

CHANGES EVERYTHING<br />

by Matt Pedersen<br />

FEATURE ARTICLES<br />

58 FISHKEEPING BASICS:<br />

Common health problems in Corydoradine catfishes<br />

by Ian Fuller<br />

66 FISH ROOM:<br />

Serious fishrooms: breeding aquarium fishes<br />

for the wholesale trade<br />

by Walter Hilgner<br />

74 HUSBANDRY & BREEDING:<br />

With flashes of brilliant color, a new blue-eye is here!<br />

by Hans-Georg Evers<br />

78 HUSBANDRY & BREEDING:<br />

Chilatherina sentaniensis: long sought, finally found<br />

by Thomas Hörning<br />

82 REPORTAGE:<br />

From Thailand: new snakeheads<br />

by Dominik Niemeier and Pascal Antler<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

88 RETAIL SOURCES<br />

90 SPECIES SNAPSHOTS<br />

94 SOCIETY CONNECTIONS<br />

98 UNDERWATER EYE<br />

AMAZONAS 3

EDITORIAL<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

4<br />

Dear Reader,<br />

AMAZONAS founding editor Hans-Georg Evers<br />

It has actually taken a lot of work to reach a point where we could present a classic genus<br />

to a public that is interested in more than just colorful pictures accompanied by the same<br />

old stale verbiage. Unfortunately, many classic aquarium fishes suffer from being considered<br />

“common” beginners’ fishes and, hence, beneath the interest of advanced aquarists.<br />

But the freshwater angelfishes in the genus Pterophyllum are quite a special genus of cichlids.<br />

With just three recognized species, the group is easy to summarize, but also includes<br />

both easy-to-keep “bread and butter” fishes, with numerous exotic strains and cultivated<br />

forms, and rare wild forms that are often very difficult and time-consuming to keep and<br />

breed.<br />

We want to use this issue to spread the word among aquarists who have been working<br />

extensively with angelfishes for many years and know what they are doing. That may<br />

sound highly contradictory, but it won’t deter us from our goal of introducing these<br />

majestic fishes to our readers. We have deliberately placed the emphasis on the wild forms,<br />

in order to increase awareness of these beautiful fishes. In the past there have been real<br />

battles of opinion in certain circles, especially regarding the majestic Altum. So don’t be<br />

surprised if some statements in the individual articles appear somewhat contradictory.<br />

One thing is crystal clear, however. <strong>Angels</strong> are gorgeous fishes for beginners and experts<br />

alike. I am quite sure that after reading our cover feature you will pay more attention the<br />

next time you find yourself standing in front of a tank of angelfishes.<br />

We also have a couple of real stunners in this issue. The very attractive Paska’s Blue-<br />

Eye has been tracked down and is being bred—and a new star in the mini-fish heavens has<br />

found its way into the aquarium. We take you with us for a look inside the fishrooms of<br />

Walter Hilgner, a truly passionate breeder of many desirable fish species and a former hobbyist<br />

who admits to losing the battle with one of his aquarium “addictions.” And readers<br />

of our English edition will find an enlightening piece by Ian Fuller on the mystery of sudden<br />

death and the treatment of other maladies peculiar to Corydoradinae catfishes.<br />

I wish you happy reading and continued enjoyment of the aquarium hobby!

The world is yours.<br />

The earth is composed of water—71.1% to be exact. But when it comes to<br />

tropical fi sh, we’ve really got it covered. Not only with exotic varieties from<br />

around the globe, but with the highest level of quality, selection and vitality.<br />

Ask your local fi sh supplier for the best, ask for Segrest.<br />

Say Segrest. See the best. <br />

QUALITY, SERVICE & DEPENDABILITY<br />

<br />

AMAZONAS 5

AQUATIC<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

6<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

by Dr. Mark Sabaj Pérez—Special Report to AMAZONAS<br />

Damming the Río Xingu: field update<br />

With the specter of an ecosystem-killing hydroelectric<br />

dam project moving ahead in Brazil, the eyes of many<br />

concerned observers, especially those interested in the<br />

fate of native fish species, are on the Lower Xingu River.<br />

For two weeks, from October 3–17, I joined Brazilian<br />

colleagues on a fishing expedition to the Lower<br />

Xingu near Altamira, Brazil. (I am Collection Manager<br />

of Fishes at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.)<br />

During this time of year, the Xingu is at its lowest<br />

seasonal point, and many species of fish become crowded<br />

together, making them easier to find and catch.<br />

The collecting group included Dr. Leandro Sousa, a<br />

professor at the Universidade Federal do Pará, Altamira<br />

campus, who is part of a team of Brazilian scientists<br />

conducting aquatic surveys of the Lower Xingu in the<br />

stretches that will be affected by the construction of the<br />

Belo Monte Dam. Dr. Mariangeles Arce, an expert on the<br />

molecular evolution of thorny catfishes (Doradidae), is<br />

also on the team; she recently completed<br />

her doctoral degree at the Pontifícia Universidade<br />

Católica do Río Grande do Sul<br />

in Porto Alegre, Brazil.<br />

Expedition team (left to right): Edson,<br />

Zezinho, Dani, Dr. Mariangeles Arce,<br />

Dr. Mark Sabaj Pérez, Dr. Leandro Sousa.<br />

Damming and diversion of the Río Xingu,<br />

below, will displace tens of thousands<br />

of indigenous people in the heart of the<br />

Amazon basin and threaten native stocks<br />

of fishes caught for food and export<br />

to aquarists.

The expedition consisted of four separate trips. The<br />

first was a day trip by car to a tributary of the Río Penatecaua,<br />

a small, isolated tributary of the Amazon about<br />

50 miles (80 km) west-southwest of Altamira on Route<br />

230. The second was another day trip, this time by boat<br />

(voadeira in Portuguese), to a<br />

shoal made up of sand, gravel,<br />

and platelike conglomerates and<br />

a rocky outcrop in the Río Xingu<br />

about 9 miles (15 km) upstream<br />

from Altamira.<br />

The third and fourth trips<br />

were also by voadeira. On the<br />

third we ventured upstream on<br />

the Xingu to its major left-bank<br />

tributary, the Río Iriri, and then<br />

proceeded about 9 miles (15 km)<br />

up the Iriri to a large waterfall,<br />

Cachoeira Grande. The fourth<br />

trip took us downstream of Altamira,<br />

into the large, bell-shaped<br />

curve in the Lower Xingu called<br />

Volta Grande (Big Bend) and as<br />

far as Cachoeira do Jericoá, about<br />

34 miles (55 km) east-southeast<br />

of Altamira, where the Xingu<br />

suddenly drops through a series<br />

of powerful waterfalls. We also<br />

made a stop at the Río Bacajá, a<br />

small right-bank tributary of the<br />

Xingu. Two of the most skilled<br />

and respected pleco fishermen<br />

in Altamira, Dani and Edson, as<br />

well as our skipper, Zezinho, and<br />

our cook, Rai, accompanied us on<br />

the last two trips.<br />

The expedition netted and<br />

preserved about 2,500 specimens,<br />

including tissue samples of about<br />

350 individuals for molecular<br />

analysis, from a total of 11<br />

Scobinancistrus aureatus, described<br />

by Burgess in 1994 from the Lower<br />

Xingu. Known as the Sunshine<br />

Pleco or Goldie Pleco, it is one<br />

of the species threatened with<br />

extinction by the Belo Monte<br />

project.<br />

sites. The pleco hunting was<br />

extremely good, with about 25<br />

species recorded, most caught<br />

by Dani and Edson. Highlights<br />

included two species of Scobinancistrus<br />

(S. aureatus and S.<br />

paRíolispos), three species of<br />

Baryancistrus (B. chrysolomus,<br />

B. niveatus, and B. xanthellus), the rare Leporacanthicus<br />

heterodon, two species of Hypancistrus, H. zebra and<br />

one undescribed (L174), two or three Spectracanthicus,<br />

including one undescribed (L020), and a beautiful specimen<br />

of an undescribed Pseudacanthicus (L025).<br />

The specimens were divided between and vouchered<br />

at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and<br />

Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia in Manaus,<br />

capital of the Brazilian state of Amazonas. The purposes<br />

of the expedition were 1) to collect additional specimens<br />

and tissue samples of undescribed species under study<br />

by Mark, Leandro, Mariangeles, and colleagues; 2) to<br />

take photographs of live fishes, their habitats, and the<br />

conditions of the river; 3) to test logistics and collecting<br />

gear for future expeditions to the Lower Xingu; and<br />

4) to contribute to baseline estimates of fish diversity in<br />

vaRíous stretches of the Lower Xingu pRíor to its modification<br />

by the Belo Monte Dam complex. The expedition<br />

was funded in part by a generous donation from Julian<br />

Dignall and PlanetCatfish.<br />

Dam construction in progress<br />

Construction on the Belo Monte Dam complex appears<br />

to be progressing swiftly, despite legal challenges and the<br />

protests of indigenous tribes whose lands and livelihoods<br />

are threatened.<br />

We did not visit the construction site, but caught<br />

a glimpse of the temporary low dam of rocks, sand,<br />

and mud being built across the entire channel in the<br />

upstream portion of Volta Grande (a site known as Pimental).<br />

Here the river channel is divided into a number<br />

of streams by islands and small shoals. The low dam<br />

has been creeping across the Xingu all year, and now<br />

only the largest section of the river, along the western<br />

bank, remains unimpeded. Leandro said that early in the<br />

construction, the Xingu overpowered the low dam in<br />

what was locally regarded as a big victory for nature. But<br />

since then, the dam builders have been the victors. From<br />

time to time, groups of indigenous peoples gather at the<br />

construction site to protest the dam. Their protests are<br />

largely peaceful and largely ignored.<br />

AMAZONAS 7

AMAZONAS<br />

8<br />

TM<br />

Top: Xingu version of Peckoltia sabaji,<br />

a species described by Armbruster in<br />

2003 based on Essequibo specimens.<br />

Bottom: New species of Hypancistrus<br />

(L174) to be described by Leandro<br />

Sousa, found along rocky ledges over<br />

52 feet (16 m) deep. Deep water habitat<br />

may become scarce for such species<br />

after water is diverted from Volta Grande.<br />

Toward the end of our expedition,<br />

the rainy season began and the Xingu<br />

started to rise. Presumably, construction<br />

of the dam will be suspended,<br />

given the increased flow of the river.<br />

Once the river subsides again next<br />

year, the low dam (assuming it<br />

remains intact) will not take long to<br />

complete. Eventually, a more permanent<br />

dam will be built at Pimental,<br />

impounding the Lower Xingu to form the Calha do Xingu Reservoir, which<br />

will extend upstream to about half the distance between Altamira and the<br />

mouth of the Río Iriri. From the reservoir, the Xingu’s water will be diverted<br />

through two large canals being dug toward Belo Monte near the downstream<br />

limit of Volta Grande.<br />

Some have estimated that more earth is being displaced for these diversion<br />

canals than was removed during the construction of the Panama Canal. The<br />

portion of Volta Grande that is not inundated by the reservoir will be effectively<br />

“short-circuited” by the canals. No one knows exactly how much water will be<br />

diverted through the canals to generate electricity via Belo Monte. Therefore, no<br />

one knows exactly how much water will remain to fill the complex labyrinth of<br />

narrow channels that make up the downstream portion of Volta Grande.<br />

Experts estimate that Volta Grande will retain only one-third of the water<br />

it normally contains at flood level. In the low-water season, many of the shallow<br />

channels could become isolated and go completely dry, resulting in heavy<br />

losses for resident fishes and other aquatic organisms. One thing is for sure:<br />

much of the Belo Monte Dam complex will be completed soon…perhaps by<br />

the end of the next dry season.

The Wait Is Over<br />

Once upon a time the way to start an<br />

aquarium involved introducing a few<br />

hardy fishes and waiting one to two<br />

months until the tank “cycled.”<br />

Nowadays the startup of aquariums<br />

is so much simpler, and faster too!<br />

BioPronto TM FW contains cultured<br />

naturally occuring microbes that<br />

rapidly start the biological filtration<br />

process. Use it to start the<br />

nitrification cycle in new aquariums<br />

or to enhance nitrification and<br />

denitrification in heavily stocked<br />

aquariums. What are you waiting for?<br />

It’s time to make a fresh start.<br />

Two Little Fishies Inc. 1007 Park Centre Blvd.<br />

Miami Gardens, FL 33169 USA www.twolittlefishies.com<br />

Fritz Complete Full-Spectrum Water Conditioner - Eliminates Ammonia, Nitrite, Nitrate, Chlorine, Chloramine<br />

FritzZyme® 7 The Original Live Nitrifying Bacteria - Establishes a healthy biofilter with proven freshwater-specific bacteria<br />

MADE IN THE USA : Available at aquarium specialty stores. To find a dealer near you, visit www.FritzAquatics.com<br />

AMAZONAS 9

AQUATIC<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

10<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

A new mailed catfish<br />

of the Corydoras aeneus group<br />

Above: Male<br />

Corydoras sp.<br />

CW 68<br />

by Erik Schiller In September 2009 my friend Ingo Seidel told me that he had<br />

obtained a new mailed catfish with attractive yellow fins, which was slightly reminiscent<br />

of Corydoras zygatus. The good news was that the collecting locality for this “new<br />

species” was known. Jens Gottwald had caught the fishes at the Río Aripuaná in Brazil.<br />

This fish has received the code number CW 68 on Ian Fuller’s CorydorasWorld site.<br />

Corydoras zygatus, the Blackband Cory, comes from Peru, from the Río Huallaga system in the Río<br />

Santiago. However, locations are also known from the Río Pindo in Ecuador. Because the distances<br />

between these locations in Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil (Río Aripuaná) are extremely large, I originally<br />

called this new mailed catfish from the Río Aripuaná Corydoras sp. “Río Aripuaná”. But because the<br />

species has now been classified as CW 68, this code number should be used instead.<br />

Corydoras sp. CW 7 is another similar species. The precise location for this species is not<br />

known, but it is a bycatch with Corydoras zygatus. So these catfishes definitely don’t come from<br />

Brazil!<br />

Naturally, I was very interested, but my space is limited, with 25 aquariums. So for the time<br />

being, Ingo kept the small group of specimens. But because he had also acquired a large number of<br />

other new catfishes, there was no question of breeding the Corydoras from the Río Aripuaná right<br />

away. Two years passed before I picked up three Corydoras from Ingo in September 2011. Unfortunately,<br />

there was no longer any sign of the yellow fins, but in both sexes the dark stripe above the<br />

midline was readily visible. I received a trio of one female and two males—a good starting point for<br />

successful breeding.<br />

SEIDEL I.

I. SEIDEL<br />

Spawning at low pressure<br />

The Corydoras sp. CW 68 were given a 60-L (15-gallon) aquarium with fine sand and a large<br />

piece of bogwood as shelter. After good feeding with live food, the female rapidly developed<br />

eggs. These catfish were extremely retiring in their habits. I only rarely saw them at feeding<br />

time. That changed a little when I introduced eight Nannostomus beckfordi.<br />

While many mailed catfishes change color during courtship and the spawning process,<br />

with the coloration of male specimens becoming bolder and that of females a little paler, this<br />

pattern is completely reversed in Corydoras sp. CW 68. After several water changes with cooler<br />

water, the base color of the males lightened up. The catfish were iridescent greenish below<br />

Above: When they are<br />

about six weeks old and<br />

.75 inch (2 cm) long, a<br />

bluish iridescent spot<br />

appears on the young<br />

fishes’ sides.<br />

Below: The females of<br />

CW 68, with their plump<br />

body form, are particularly<br />

reminiscent of Corydoras<br />

zygatus from Peru.<br />

AMAZONAS 11

AQUATIC<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

12<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

the midline. Under lateral lighting this makes a nice<br />

color combination with the post-occipital scute, which<br />

changes color to yellowish. The dark stripe becomes even<br />

more prominent in females. Excited swimming around in<br />

the evening during a period of falling barometric pressure<br />

made me hopeful. But early the next day, all the fish were<br />

once again resting quietly beneath the bogwood. After<br />

feeding them with live Artemia I went to work. Great was<br />

my jubilation when I came back to my fish room and saw<br />

that the corners of the aquarium were full of eggs. After<br />

collecting and transferring them to a separate container I<br />

counted around 80 eggs.<br />

Manage Your Own<br />

Subscription<br />

It’s quick and user friendly<br />

Go to www.AmazonasMagazine.com<br />

Click on the SUBSCRIBE tab.<br />

Here you can:<br />

● Change your address<br />

● Renew your subscription<br />

● Give a gift<br />

● Subscribe<br />

● Buy a back issue<br />

● Report a damaged or missing issue<br />

Other options:<br />

EMAIL us at:<br />

service@amazonascustomerservice.com<br />

CALL: 570-567-0424<br />

Or WRITE:<br />

Amazonas Magazine<br />

1000 Commerce Park Drive, Suite 300<br />

Williamsport, PA 17701<br />

Problem-free rearing<br />

The first larvae hatched after five days at 23°C (73°F).<br />

All the fertilized eggs (around 90 percent) hatched into<br />

catfish larvae. Another four days later the fry were managing<br />

freshly hatched Artemia nauplii without problems.<br />

Just a day after they started feeding the fry began to show<br />

color. A dark band developed, starting in the head region<br />

and running to the pectoral fin insertion. As a result the<br />

head appeared to be separated from the rest of the body.<br />

After around five more days, several dark dots appeared<br />

along the back. After 14 days the head region,<br />

set off by the black band, looked more yellowish and<br />

created a contrast with the rest of<br />

the finely dotted body. There were<br />

four large, dark dots along the line<br />

of the dorsum, and a further row<br />

of smaller dots marked the midline,<br />

below which occasional additional<br />

dots could be seen. The size of the<br />

little catfishes was now around .5<br />

inch (1.3 cm).<br />

After a further 10 days, when the<br />

fish were almost five weeks old, the<br />

transparent base color was replaced<br />

by a yellowish shade. At this age the<br />

catfish averaged about .7 inch (1.8<br />

cm) long. At a length of around .75<br />

inch (2 cm) a dark, bluish, iridescent<br />

spot developed beneath the<br />

dorsal fin. This spot grew longer with<br />

increasing age. In this way the broad,<br />

dark band typical of Corydoras sp.<br />

CW 68 developed. And the yellowish-looking<br />

post-occipital scute also<br />

became apparent at this time.<br />

Next time, I caught the Golden<br />

Pencilfish out of the tank and added<br />

an airstone to circulate the water vigorously<br />

in one corner of the aquarium.<br />

Two days later I was able to<br />

watch the Corydoras trio spawning.<br />

The eggs were distributed at random<br />

around the aquarium. Each time four<br />

to eight eggs were transported by the<br />

female in her pelvic-fin pouch and<br />

attached to a substrate. A day later<br />

the eggs looked milky. Again, there<br />

were around 80 of them.<br />

Even though Corydoras sp. CW<br />

68 isn’t a miracle of color, it is still a<br />

further new species that we haven’t<br />

ever been able to keep in our aquariums<br />

before.<br />

ON THE INTERNET<br />

www.corydorasworld.com

Advanced aquarists choose from a proven leader in<br />

product innovation, performance and satisfaction.<br />

INTELLI-FEED<br />

Aquarium Fish Feeder<br />

Can digitally feed up to 12 times daily<br />

if needed and keeps fish food dry.<br />

QUIET ONE® PUMPS<br />

A size and style for every need... quiet... reliable<br />

and energy efficient. 53 gph up to 4000 gph.<br />

MODULAR<br />

FILTRATION<br />

SYSTEMS<br />

Add Mechanical,<br />

Chemical, Heater<br />

Module and UV<br />

Sterilizer as your<br />

needs dictate.<br />

AIRLINE<br />

BULKHEAD KIT<br />

Hides tubing for any<br />

Airstone or toy.<br />

FLUIDIZED<br />

BED FILTER<br />

Completes the ultimate<br />

biological filtration system.<br />

BIO-MATE®<br />

FILTRATION MEDIA<br />

Available in Solid, or refillable<br />

with Carbon, Ceramic or Foam.<br />

BULKHEAD FITTINGS<br />

Slip or Threaded in all sizes.<br />

AQUASTEP<br />

PRO® UV<br />

Step up to<br />

new Lifegard<br />

technology to<br />

kill disease<br />

causing<br />

micro-organisims.<br />

LED DIGITAL THERMOMETER<br />

Submerge to display water temp.<br />

Use dry for air temp.<br />

Visit our web site at www.lifegardaquatics.com<br />

for those hard to find items... ADAPTERS, BUSHINGS, CLAMPS,<br />

ELBOWS, NIPPLES, SILICONE, TUBING and VALVES.<br />

Email: info@lifegardaquatics.com<br />

562-404-4129 Fax: 562-404-4159<br />

Lifegard® is a registered trademark of Lifegard Aquatics, Inc.<br />

13

AQUATIC<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

14<br />

Right: Preserved<br />

specimen of<br />

Panaqolus koko from<br />

the Maroni.<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

Above: Preserved<br />

specimen of Peckoltia otali<br />

from the Maroni River.<br />

Four new loricariid catfishes described<br />

from the Guiana Shield<br />

article and images by Ingo Seidel With the aid of a new molecular biological technique<br />

known as DNA barcoding, ichthyologists Fisch-Muller, Montoya-Burgos, Le Bail, and<br />

Covain have sought to clarify the phylogenetic relationships of a number of ancistrines<br />

of the Panaque assemblage from the Guiana Shield. In so doing they simultaneously<br />

described four loricariid catfish species so far unknown in the aquarium hobby and<br />

undertook a redescription of Hemiancistrus medians, the type species of its genus.<br />

As an important byproduct of their research results, Fisch-Muller, Montoya-Burgos, Le Bail, and Covain<br />

(2012) undertook the long overdue validation of the genus Panaqolus, which for years has been<br />

regarded as a synonym of Panaque by leading ichthyologists (e.g. Armbruster 2004). It seems, however,<br />

that despite their very similar dentition, there are no close phylogenetic links between the two

genera; instead, Panaqolus is thought to be very closely<br />

related to the genus Peckoltia, whose members are very<br />

similar in appearance and size.<br />

New Peckoltia species<br />

A total of three species of the genus Peckoltia and one<br />

Panaqolus species were newly described from French<br />

Guiana and Surinam. The new Peckoltia simulata from<br />

the River Oyapock, which forms the<br />

border between French Guiana and<br />

Brazil, is very similar to Peckoltia<br />

oligospila (also known as L 006)<br />

from the Brazilian federal state of<br />

Pará. The species is apparently not<br />

identical with the similar Peckoltia<br />

species L 055, which has purportedly<br />

been imported in the past from that<br />

river and has dark cross-bands on<br />

the caudal fin (which is dark-spotted<br />

in P. simulata and P. oligospila).<br />

I am unaware of there being<br />

any specimens of this species in the<br />

aquarium hobby to date, and the<br />

same applies to the species Peckoltia<br />

capitulata, which is native to the<br />

River Approuage. Unfortunately, for<br />

this reason I am unable to provide<br />

pictures of these species here. So far<br />

both Peckoltia species are known only<br />

from specimens with a maximum<br />

total length of some 3–4 inches<br />

(8–10 cm), but that may not be the<br />

absolute eventual size of these species.<br />

Peckoltia capitulata possesses a<br />

somewhat more elongate body than<br />

P. simulata and likewise exhibits<br />

black spots, but these are absent on<br />

the head region and elsewhere widen<br />

into broad crossbands.<br />

By chance I obtained a number<br />

Hemiancistrus<br />

medians is the only<br />

species of its genus.<br />

Below is a young<br />

specimen.<br />

Left: View of<br />

the unusual<br />

dentition of<br />

Panaqolus koko.<br />

Right: View of<br />

the dentition<br />

and papillae of<br />

Hemiancistrus<br />

medians.<br />

of specimens of the other two new species, Peckoltia otali<br />

and Panaqolus koko, from my friend Jens Gottwald, who<br />

had preserved them for scientific purposes during a collecting<br />

expedition by Panta Rhei GmbH from Hannover.<br />

Both species occur together in the Maroni, the river that<br />

forms the border between French Guyana and Surinam.<br />

So I am now in the fortunate position of being able to<br />

illustrate at least these two species here.<br />

AMAZONAS 15

AMAZONAS<br />

16<br />

AQUATIC<br />

Peckoltia otali is another 3–3.5-inch (8–9-cm) long brown Peckoltia species<br />

with black spots connecting to form irregular bands. It is one of the smaller<br />

Peckoltia species in which males are very heavily bristled, and may be fairly<br />

closely related to two species well known in the aquarium hobby, namely L<br />

038 and L 080. Hence it is not surprising that during the bar-coding, Fisch-<br />

Muller et al. established striking differences between this and the other two<br />

new Peckoltia species, which they classified as genetically fairly close to P.<br />

oligospila.<br />

The species Panaqolus koko is likely to be the subject of future major discussion<br />

among ichthyologists, as it is a very unusual fish. When I examined<br />

this species in detail before the publication of its description, I classified it as a<br />

member of an undetermined genus, as the combination of body form, odontode<br />

(dermal tooth) growth, and dentition distinguished it from all other<br />

genera known to me to date.<br />

I found its assignment to the genus Panaqolus very surprising, as all other<br />

members of the genus that I am aware of possess a broader body form and<br />

spatulate teeth with a single cusp. Only Panaqolus maccus purportedly (according<br />

to Schaefer & Stewart 1993) exhibits a certain variability in dentition<br />

when young, with a possible second cusp.<br />

The new Panaqolus koko is uniform black-brown in color, with an unusually<br />

pointed head and slender form. All the specimens I have examined are<br />

thought to be half-grown and already have unusually striking odontodes such<br />

as I have never previously seen in any other Panaqolus species at this age. And<br />

while the teeth were spatulate overall, they were unusually large and possessed<br />

a second large lateral cusp. The species may attain a total length of around<br />

4.3–4.7 inches (11–12 cm).<br />

Is Hemiancistrus monotypic?<br />

Ichthyologists have hitherto avoided differentiating the catch-all genus Hemiancistrus<br />

from Peckoltia; in the past it has been a depository mainly for assorted<br />

black-spotted armored catfishes that don’t fit well in other genera. But<br />

Fisch-Muller et al. have established that Hemiancistrus medians, type species of<br />

the genus Hemiancistrus, is not closely related to Peckoltia and Panaqolus.<br />

The authors believe the genus Hemiancistrus should be regarded as monotypic,<br />

as the other species currently assigned to this genus are probably not<br />

closely related to the type species.<br />

Hemiancistrus medians is a very unusual loricariid, which may now also<br />

have been imported alive to Europe, probably for the first time, by Panta Rhei<br />

GmbH. This armored catfish, which grows to around 9.8 inches (25 cm) long,<br />

is most closely reminiscent of the members of the genus Baryancistrus, but<br />

has unusually large eyes, heavily ridged scutes on the sides of the body, and<br />

truly extraordinary papillae in the mouth cavity. The smaller specimens have<br />

noticeably fewer, but extremely large black spots on the body, and these become<br />

smaller and more numerous with increasing age. These black spots look<br />

very attractive on the yellowish-brown background.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

Armbruster, J.W. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of the suckermouth armoured catfishes<br />

(Loricariidae) with emphasis on the Hypostominae and the Ancistrinae. Zool J Linn Soc 141: 1–80.<br />

Fisch-Muller, S., J.I. Montoya-Burgos, P.-Y. Le Bail, and R. Covain. 2012. Diversity of the Ancistrini<br />

(Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Guianas: the Panaque group, a molecular appraisal with<br />

descriptions of new species. Cybium 36 (1): 163–93.<br />

Schaefer, S.A. D.J. Stewart. 1993. Systematics of the Panaque dentex species group (Siluriformes:<br />

Loricariidae), wood-eating armored catfishes from tropical South America. Ichthyol Expl Freshw 4 (4):<br />

309–42.

AMAZONAS 17

AQUATIC<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

18<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

article and images by Hans-Georg Evers<br />

New Rams<br />

Above: The<br />

“Super Neon<br />

Blue Gold”<br />

ram’s behavior<br />

is similar to that<br />

of the wild form.<br />

The light falling<br />

from above<br />

accentuates the<br />

orange body<br />

color of the male<br />

in the middle.<br />

Right: Lovely<br />

male of the new<br />

“Super Neon<br />

Blue Gold”,<br />

bred by Peter<br />

Günnel.<br />

The breeding skill of the well-known breeder Peter<br />

Günnel, Sr., has recently produced a number<br />

of very attractive new cultivated forms of the<br />

popular Butterfly Dwarf Cichlid Mikrogeophagus<br />

ramirezi. It seems he has gotten hooked<br />

on rams, with the goal of breeding new, stable<br />

forms from the “Electric Blue” cultivated form<br />

by in-crossing particularly high-backed German<br />

strains. He has now achieved this goal, and<br />

he admitted to me that he is proud of<br />

what is probably his loveliest cultivated<br />

form so far.<br />

The “Super Neon Blue Gold” has been in<br />

the trade for some months now. I obtained a<br />

number of specimens of this lovely cultivated<br />

form, whose body base color is a brilliant<br />

orange-gold, from Peter via the firm Von Wussow<br />

Importe (Pinneberg). Adult males exhibit a<br />

powerful body form with iridescent turquoiseblue<br />

dots on the sides of the body and a gorgeous<br />

blue coloration on all the fins. The<br />

dorsal fin is edged with orange. Males<br />

also exhibit this orange on the<br />

head region, especially on the

“Wow!”<br />

Become a charter subscriber to AMAZONAS<br />

and don’t miss a single issue!<br />

Use the convenient reply card in this issue, or subscribe online:<br />

www.AmazonasMagazine.com<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

Volume 2, Number 1<br />

January/February 2013<br />

AMAZONAS 19

20<br />

Does size matter to you ?<br />

We bet it does. Trying to clean algae off the glass in a planted aquarium with your typical algae magnet is like running a bull<br />

through a china shop. That’s why we make NanoMag ® the patent-pending, unbelievably strong, thin, and flexible magnet for cleaning<br />

windows up to 1/2” thick. The NanoMag flexes on curved surfaces including corners, wiping off algal films with ease, and it’s so much fun to<br />

use you just might have to take turns. We didn’t stop there either- we thought, heck, why not try something smaller? So was born MagFox ® ,<br />

the ultra-tiny, flexible magnetically coupled scrubber for removing algae and biofilms from the inside of aquarium hoses.<br />

Have you got us in the palm of your hand yet?<br />

www.twolittlefishies.com

DANIEL CASTRANOVA (© NIH/NICHD)<br />

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

The females, too, are a brilliant blue.<br />

Male of the new “Perlmutt”<br />

cultivated form.<br />

Females of the “Perlmutt”<br />

cultivated form positively<br />

shimmer.<br />

forehead. Even the females of this lovely cultivated form are a brilliant light<br />

blue, but they don’t exhibit the orange quite as strongly.<br />

A second new form, also bred by Peter Günnel, is called Mikrogeophagus<br />

ramirezi “Perlmutt”. Particularly in females, the mother-of-pearl effect is accentuated<br />

by a large number of highly reflective metallic scales.<br />

We now have two more very attractive cultivated forms of the Butterfly<br />

Dwarf Cichlid to admire.<br />

Who knows what the future holds next for rams?<br />

TM

AMAZONAS<br />

22<br />

Revolutionary<br />

Lighting<br />

Technology<br />

Optimized Refl ector Design<br />

Channels 95% of emitted<br />

light to maximize energy<br />

effi ciency. LEDs manufactured<br />

by Cree and Osram.<br />

Broad Light Distribution<br />

One Radion will provide optimum<br />

lighting for around 40 gallons<br />

(150 liters) of tank volume.<br />

Simple Interface<br />

Super-easy three-button<br />

controllability on the fi xture.<br />

Graphic-driven PC interface<br />

after USB connect for<br />

advanced functionality.<br />

INTENSITY RadionTM<br />

Customizable Spectrum<br />

Full-spectrum output allows<br />

signifi cant PAR peaks to be<br />

targeted. Five-channel color<br />

adjustment enables custom<br />

spectrum choice based on<br />

aesthetic or photosynthetic<br />

requirements.<br />

EcoSmart TM Enabled<br />

RF wireless communication<br />

between Radion fi xtures<br />

and EcoSmart-equipped<br />

VorTech Pumps.<br />

XR30w<br />

www.ecotechmarine.com<br />

®<br />

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

Breeding Corydoradinae Catfish (Second Edition)<br />

by Ian Fuller<br />

<br />

Available from www.corydorasworld.com<br />

Book review by Hans-Georg Evers<br />

Ian Fuller, an expert on mailed catfishes whose fame extends far beyond his<br />

native England, has brought out an updated, greatly expanded and comprehensive<br />

edition of his 2001 book on breeding Corydoradine catfishes, which<br />

has long been out of print. The new self-published work can be ordered on the<br />

author’s website. Fuller has obtained help from a number of other breeders,<br />

and the new book details breeding success and fry development in more than<br />

150 species.<br />

After an introductory section encompassing more than 30 pages on his<br />

breeding set-up, with numerous detailed photos, tables, and loads of information<br />

on methods of breeding mailed catfishes, we come to the 330-page heart<br />

of the book, the “spawning logs,” where at least two pages are devoted to<br />

discussing each species using a clear and readable style.<br />

In Breeding Corydoradinae Catfish, Ian Fuller has published a wealth of<br />

information on the reproductive biology of one of the most popular of all<br />

catfish families. It is a reference volume that should be of interest to every expert<br />

aquarist, not just fans of corys and their kin. Trends come and go in the<br />

aquarium hobby, but Ian Fuller has dedicated his life to the study of mailed<br />

catfishes. This big new book will be welcomed by many aquarists.<br />

H.-G. EVERS

RadionTM<br />

Sleek. Sophisticated. High-tech. Beautiful.<br />

The new Radion Lighting features 34 energy-effi cient LEDs with fi ve color families.<br />

Improved growth. Wider coverage. Better energy effi ciency. Customizable spectral output.<br />

In short, a healthier, more beautiful ecosystem.<br />

EcoTech Marine. Revolutionizing the way people think about aquarium technology.<br />

www.ecotechmarine.com<br />

®<br />

AMAZONAS 23

AMAZONAS<br />

24<br />

COVER<br />

STORY<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 1 from<br />

the Río Nanay in Peru. The<br />

reddish brown spots on<br />

the flanks are typical. This<br />

species is also erroneously<br />

known as the “Peruvian<br />

Altum” because of its<br />

mouth form and<br />

body height.<br />

The latest on Pterophyllum:<br />

species and forms of angelfishes<br />

by Heiko Bleher For years there has been disagreement regarding the names of the<br />

various angelfishes we keep and the species to which they belong. Heiko Bleher<br />

shares his personal experiences and discusses the forms he has collected during<br />

his travels and imported for the aquarium hobby.<br />

I first made the acquaintance of an angelfish in the early 1950s, in my mother’s fish and plant hothouse<br />

in Frankfurt on Main, where, as a little lad, I had to keep out of the way of her free-roaming 6.5-foot (2-m)<br />

caiman. The daughter of Adolf Kiel, the “Father of Water Plants,” my mother had inherited his passion for<br />

adventure and collecting wild things, something she passed on to me. It was also she who told me about the nomenclatural<br />

confusion attaching to the angelfish: in 1758, Carl von Linné, the father of the binomial scientific<br />

nomenclature of all species, assigned a number of fish species to the genus Zeus.<br />

It was Schultze who first described the species Zeus scalaris in a work by Hinrich Lichtenstein (1823), from<br />

N. KHARDINA

TOP LEFT: N. KHARDINA; OTHERS: H. BLEHER<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 5, from the Río Apaporis in Colombia.<br />

a specimen from the Amazon River, purportedly from Barra, the<br />

mouth area of the Río Negro.<br />

Nomenclatural confusion<br />

But eight years later, Cuvier reassigned the angelfish to the marine<br />

genus Platax and called it Platax ? scalaris from “Bresil” (Cuvier<br />

& Valenciennes 1831). Next, Jakob Heckel erected the genus<br />

Pterophyllum (meaning “leaflike fins”) in 1840 and assigned the<br />

species the new name of Pterophyllum scalaris.<br />

Then, François de Castelnau, a French naturalist, described<br />

another angelfish, which he collected from “Pará, Bresil”<br />

during his Amazon expedition (1842–1847), as Plataxoides<br />

dumerilii Castelnau, in 1855, although Heckel<br />

had established Pterophyllum as the name of the<br />

genus some 15 years before.<br />

The confusion did not stop, as additional<br />

angelfishes were collected in the lower course of<br />

the Atabapo, an extreme blackwater tributary of the<br />

Río Guviare, which empties into the upper Orinoco.<br />

The Atabapo forms the border between Colombia and<br />

Venezuela for almost its entire length. In 1903 one of the<br />

best-known ichthyologists, Jacques Pellegrin, described the angelfishes<br />

caught there as a subspecies of Pterophyllum scalare and<br />

called them Pterophyllum scalare altum. The name related to the<br />

unusually high body form and size. To the present day this is the<br />

largest angelfish, the most majestic, elegant, and extraordinary of<br />

them all.<br />

My mother told me that the most recently described angelfish,<br />

Pterophyllum eimekei Ahl, 1928, may be the smallest, and<br />

supposedly originates from the Río Negro. But later on, just like<br />

P. dumerilii, it was regarded as a synonym of P. scalare. However,<br />

in my opinion, P. eimekei is definitely a valid species.<br />

Despite all the scientific attention, it wasn’t until 1907 that<br />

an importation of live specimens from the lower Amazon region<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 3<br />

is endemic to the Río<br />

Jutai in Brazil.<br />

Pterophyllum<br />

sp. 2 from the<br />

drainage of Lago<br />

Paricatuba, lower Purus<br />

basin, in Brazil. Note the threadlike<br />

extensions to the anal fin.<br />

Right: The striking coloration at the<br />

base of the dorsal fin is species-typical<br />

for Pterophyllum sp. 3 from<br />

the Río Jutai.<br />

I discovered this eight-banded<br />

species, Pterophyllum sp. 4, in the<br />

Brazilian Río Demini, a tributary<br />

of the middle Río Negro.<br />

AMAZONAS 25<br />

25

AMAZONAS<br />

26<br />

Pterophyllum altum<br />

from the Río Ventuari in<br />

Venezuela, a tributary of<br />

the upper Orinoco.<br />

Pterophyllum<br />

altum from the Río<br />

Atabapo, upper<br />

Orinoco basin, the<br />

type locality of the<br />

species.<br />

Right: Pterophyllum sp. 6 lives in<br />

Lago Aiapuá, lower Purus basin,<br />

Brazil.<br />

reached Germany. The first successful<br />

breeding took place in 1911, although<br />

the breakthrough in the breeding of the<br />

angelfish, then known as the “king of<br />

aquarium fishes,” didn’t take place until<br />

the 1920s. The first imports to the United<br />

States date to about 1915, with two<br />

unmated fish reportedly selling for $75,<br />

a princely sum at the time and roughly<br />

equivalent to almost $2,000 in current<br />

terms. Prices began to drop in the early<br />

1920s when breeders in the both Germany<br />

and the U.S. found success.<br />

New species descriptions<br />

Between 1953 and 1955, my three siblings<br />

and I traveled with Mother through<br />

what was then the most impenetrable<br />

jungle on Earth, covering a distance of<br />

more than 1,550 miles (2500 km) under<br />

the greatest of hardships, in order to collect<br />

almost countless plants and fishes.<br />

For months on end we lived among<br />

natives, and I got to see my first wild<br />

angelfishes. Nowadays there is nothing<br />

but soybean plantations in the area—not<br />

a single virgin tree remains.<br />

Ten years later I financed my studies in ichthyology at the University of<br />

South Florida by working at one of the largest aquarium-fish farms in the<br />

world. Because the people at Gulf Fish Farm were familiar with the work<br />

of my mother and the pioneering work of my grandfather, I was asked to<br />

set up a unit for propagating aquarium plants and breeding fishes. Two<br />

buildings were made available to me. Orders, particularly for angelfishes,<br />

poured in. After some deliberation, a number of alterations, and the<br />

establishing of large ponds for the breeding of Cyclops and Daphnia, I was<br />

producing more than 10,000 angels a week, and within a month<br />

they attained a body diameter of around 1.5 inches (35–40 mm), a<br />

saleable size.<br />

Ross Socolof, the owner, was the person who introduced me to the<br />

Altum Angelfish, but it was another five years before I saw these incredibly<br />

beautiful angelfishes, whose fins can grow up to 17 inches (45 cm)<br />

high, and catch some small specimens. Starting in 1970 I imported and<br />

sold this species worldwide and made Pterophyllum altum accessible to the<br />

aquarium hobby, zoos, and enthusiasts.<br />

In 1963, ichthyologist Jean-Pierre Gosse<br />

described Pterophyllum leopoldi from the<br />

Río Solimões. However, this angelfish<br />

also occurs in the Río Negro,<br />

and in 1965 I recorded it in the<br />

Manacapuru region, where I<br />

also collected the Red-Back<br />

Angelfish and the discus that<br />

later became known as the Royal<br />

Blue. In those days, most aquarists<br />

weren’t so interested in wild-caught<br />

angels; tank-breds predominated. In ad-<br />

TOP: AQUAPRESS/H.-J. MAYLAND; OTHERS: H. BLEHER

H. BLEHER<br />

dition, it turned out that the Red-Back Angel hardly ever displays<br />

its bright red color under less than optimal maintenance, and<br />

usually looks rather like Pterophyllum eimekei.<br />

My Manacapuru-Amazon adventure was the first of over 400<br />

collecting trips I have made to the Amazon region, where I have<br />

always kept an eye out for angelfishes. As recently as December<br />

2011 I recorded a variant in a lagoa a long way from the Río Yavari<br />

(which forms the boundary between Peru and Brazil).<br />

Forms and species<br />

Here I will list the forms of angelfishes that I have recorded over<br />

the course of many years. They include what are possibly new species,<br />

and they are certainly distinguishable from one another on<br />

the basis of external appearance.<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 1: This angelfish is found only in the Río<br />

Nanay drainage and is clearly recognizable by the black spot situated<br />

dorsally below the start of the long dorsal rays and extending<br />

vertically on the dorsum. In no other angel is this so distinctly<br />

expressed. In addition, this form is almost always characterized<br />

by its rust-brown spots, sometimes distributed all over the body;<br />

the slightly upturned mouth (which leads to its sometimes being<br />

confused with P. altum and known as the Peruvian Altum in the<br />

aquarium hobby); and the five or six reddish stripes on the dorsal<br />

and caudal fins.<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 2: So far, I have been able to find this angelfish<br />

only in the Lago Paricatuba drainage in the lower Purus<br />

basin. It is distinguished from all others by the veil-like prolongation<br />

of the anal fin (this is undoubtedly a good place to look for<br />

the origins of all veil-finned angels). It always has seven stripes on the dorsal<br />

fin and seven running irregularly across the caudal fin. As in the majority of<br />

angelfishes, the stripes on the anal fin are rarely expressed.<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 3: I first found this splendid angelfish many years ago<br />

(1997) in the Río Jutai (Amazonas State), and only there. It is readily recognizable<br />

by the two striking black spots (sometimes merging into one) on the<br />

Above: Pterophyllum altum from the Río<br />

Inirida in Colombia.<br />

Below: This Pterophyllum scalare from the<br />

Río Negro is often sold as tank-bred P.<br />

altum in the aquarium hobby.<br />

AMAZONAS AMAZONAS 27

AMAZONAS<br />

28<br />

base of the dorsal fin. These spots are almost always surrounded by bright blue. This angel<br />

always has a red eye and the mouth is turned slightly upward. There are six or seven stripes<br />

visible on the dorsal fin, while those on the caudal fin are only rarely apparent.<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 4: To date I have caught this form only once, and that was in the Río<br />

Demini drainage (a tributary of the Río Negro). It is the only angel I have found so far<br />

that exhibits eight striking bands.<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 5: This angel, which I found in the ichthyologically unexplored Río<br />

Apaporis (Colombia), is distinguished from all other angelfishes by its small number of<br />

dorsal-fin rays. Other differences include its large, silvery scales, the striking, large humeral<br />

spot immediately behind the eye, and the very irregular eight or nine stripes, often<br />

more like spots, on the dorsal fin. By contrast, the caudal fin has only three to four broad<br />

reddish stripes.<br />

Pterophyllum sp. 6: Like Pterophyllum sp. 5, the angel that I found in the Lago Aipauá<br />

(Río Purus basin) has larger scales. But a very striking feature is the extremely wide<br />

posterior black band extending from the extreme end of the dorsal<br />

to the last ray of the anal fin. In addition, there are five to six<br />

broad black stripes clearly visible on the dorsal, somewhat<br />

less striking on the caudal fin. The pectoral fins are the<br />

longest I have ever seen in any angelfish except Pterophyllum<br />

altum.<br />

Pterophyllum altum: This species was<br />

described by Pellegrin in 1903. Natasha<br />

Khardina and I have examined the<br />

specimens in the Paris Museum (the jar<br />

apparently hadn’t been opened since 1903).<br />

The three specimens originated from the lower<br />

Atabapo, Río Orinoco, Venezuela.<br />

Pterophyllum scalare: This species was described<br />

by Schultze in 1823 on the basis of a single specimen<br />

collected by M.H.C. Lichtenstein, zoologist and<br />

first director of the Berlin Zoo. Here I illustrate for the first<br />

time the variants that I assign to this species—all with precise<br />

collection site data. This species is often labeled as Pterophyllum<br />

altum (Río Negro Altum) in the aquarium hobby and sometimes in the<br />

Pterophyllum scalare from the Río Negro in Brazil.<br />

Pterophyllum scalare<br />

from French Guiana,<br />

possibly a distinct<br />

species?<br />

TOP: AQUAPRESS/PLANQUETTE; BOTTOM: H. BLEHER; OPPOSITE PAGE, BOTTOM RIGHT: N. KHARDINA; OTHERS: H. BLEHER

Pterophyllum cf. eimekei from Lago de Serpa<br />

in Brazil. The markings of this fish match the<br />

description in the work by Ahl (1928).<br />

The Red-Shoulder Angelfish from<br />

the Río Arapiuns, a tributary of<br />

the lower Tapajós, is classified as<br />

Pterophyllum cf. eimekei.<br />

Pterophyllum<br />

cf. eimekei<br />

from the Río<br />

Javari, Peru.<br />

The Red-Back Angelfish<br />

from Lago Manacapuru<br />

in Brazil is likewise<br />

to be assigned to<br />

Pterophyllum cf.<br />

eimekei.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

29

AMAZONAS<br />

30<br />

scientific literature. Most, if not all, of the so-called P.<br />

altum cultivated forms can be traced back to this scalare<br />

variant. Perhaps the real P. altum from the Río Atabapo<br />

is being bred for the first time as I write these words. The<br />

fishes I have seen worldwide to date under the name P.<br />

altum are not the same as the majestic fishes that I was<br />

the first to import.<br />

Pterophyllum eimekei: This angel was described by<br />

Ahl in 1928. It was described from the lower Río Negro<br />

and later declared a synonym of P. scalare. I am,<br />

however, of the opinion that this, the smallest<br />

of all the angelfishes, should be regarded<br />

as a valid species. Because this is not<br />

Pterophyllum cf. eimekei from the<br />

Río Cuiuini, often called the<br />

Santa Isabel Angelfish in the<br />

aquarium hobby, is<br />

notable for its<br />

red fins.<br />

the place to make the case for taxonomic changes (that<br />

should be reserved for a scientific publication), the form<br />

is presented here under the designation Pterophyllum cf.<br />

eimekei.<br />

I am sure that it has the largest distribution in the<br />

middle and lower Amazon basin. All the so-called Red-<br />

Shoulder and Red-Back Angelfishes from the Manacapuru,<br />

Cuiuni (aka Santa Isabel), and Tapajós should also<br />

be assigned to this form.<br />

Pterophyllum leopoldi: This angel was described by<br />

Gosse in 1963. The type locality is “Furo du village de<br />

Cuia, left bank of Ro Solimões, ca. 90 km upstreams [sic]<br />

of the Manacapuru, Brazil,” but I have also recorded it<br />

elsewhere in the Solimões and Río Negro. This angelfish,<br />

which doesn’t grow all that large, is immediately<br />

recognizable by its downturned mouth and broad, dark<br />

shoulder spot.<br />

I hope that I have managed to give a good summary<br />

and inspired further clarification of the different variants,<br />

species, and forms.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Freshly caught<br />

Pterophyllum leopoldi from<br />

the Río Negro, Brazil.<br />

Ahl, E. 1928. Übersicht über die Fischen der südamerikanischen Cichliden-<br />

Gattung Pterophyllum. Zoologischer Anzeiger v. 76 (nos 7/10) (art. 13):<br />

251–55.<br />

Cuvier, G. and A. Valenciennes. 1832. Histoire naturelle des poisons, vol. 8,<br />

book 9. Des Scombéroïdes. Pp. i–xix + 5 pp. + 1–509, pls. 209–45.<br />

Heckel, J.J. 1840. Johann Natterer’s neue Flussfische Brasilien’s nach<br />

den Beobachtungen und Mittheilungen des Entdeckers beschrieben<br />

(Erste Abtheilung, Die Labroiden). Annalen des Wiener Museums der<br />

Naturgeschichte 2: 325–471, pls. 29–30.<br />

Schultze, in Lichtenstein, M.H.C. 1823. Verzeichniss der Doubletten des<br />

zoologischen Museums der Königl. Universität zu Berlin, nebst Beschreibung<br />

... Berlin. Verzeichnis der Doubletten des zoologischen Museums der Königl.<br />

Universität zu Berlin, nebst Beschreibung: i–x, 1–118, Pl.<br />

Pellegrin, J. 1903. Description de Cichlidés nouveax de la collection du<br />

Muséum. Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Série 1), v. 9<br />

(no. 3): 120–125. TOP: N. KHARDINA; BOTTOM: H. BLEHER

H. KÖHLER<br />

AMAZONAS 31

AMAZONAS<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

32<br />

A life<br />

with<br />

angels<br />

This specimen of the Blue Angel<br />

demonstrates very nicely that it is<br />

probably a back-cross with a White<br />

Pearl Angel, as evidenced by the<br />

change in the scales on the flanks.<br />

A sight that has fascinated me all my life.<br />

My living-room tank is home to a group of<br />

Pterophyllum cf. altum from the Orinoco.

H.-G. EVERS<br />

by Bernd Schmitt Angelfishes are among the classics of the aquarium<br />

hobby, and a wide variety of cultivated forms are offered for sale. Unfortunately,<br />

many of the specimens being sold in the trade are mere<br />

shadows of the angelfishes of the past. There are, nevertheless, still wild<br />

strains that not only look attractive but also permit interesting observations.<br />

Bernd Schmitt relates his experiences, accumulated over several<br />

decades of maintaining angelfishes.<br />

As a 10-year-old boy, I made two pilgrimages every week from our town to a pond in the<br />

next village. The pond contained bright-red water fleas (Daphnia), and I quickly filled<br />

my little bucket with them. My curiosity was often aroused by a sunken greenhouse<br />

visible behind some bushes near the road, where, I learned, aquarium<br />

fishes were being bred.<br />

When I first descended the steps into this bubbling and gurgling<br />

paradise, my life changed, and the aquarium hobby’s pull has never let<br />

me go. At the rear of the greenhouse stood what was a huge aquarium<br />

in those days, with a stout steel frame. In this tank there was a pair<br />

of angelfishes, surrounded by a shoal of .75-inch (2-cm) fry. The<br />

aquarium I had then was too small to keep these splendid fishes,<br />

but that changed later on, and there have been only a few interruptions<br />

in my involvement with these fishes.<br />

Back then there were differing opinions regarding the scientific<br />

names of these fishes, and that is still the case—probably because<br />

Zebra <strong>Angels</strong>, one of the most<br />

popular cultivated forms, are bred<br />

in large numbers by professional<br />

breeders.<br />

COVER<br />

STORY<br />

Above: Ghost<br />

<strong>Angels</strong> are one<br />

of the cultivated<br />

forms that fans<br />

of wild forms find<br />

difficult to get<br />

used to.<br />

AMAZONAS AMAZONAS 33

AMAZONAS<br />

34<br />

Above, left to right:<br />

Over the<br />

generations, this<br />

strain of what used<br />

to be the Golden<br />

Angel has developed<br />

into more of a “Silver<br />

Angel” through lack<br />

of selection for color.<br />

I have been breeding<br />

this Blue Angel for a<br />

long time.<br />

A splendid Koi Angel<br />

male, bred by the<br />

Wilhelm family.<br />

Short and splayed<br />

ventral fins, short<br />

dorsal fins, and<br />

poor growth are,<br />

unfortunately,<br />

all too common.<br />

Poor-quality<br />

specimens like this<br />

one reduce the<br />

majestic angelfish to<br />

an almost circular<br />

form and shouldn’t<br />

be allowed into<br />

circulation.<br />

Right: True Black<br />

<strong>Angels</strong> are rarely<br />

seen nowadays, but<br />

the “Half-Black”<br />

cultivated form is<br />

very popular.<br />

of their vast distribution region. The discovery of more new local forms, coupled with a lack of<br />

any serious systematic study of this wealth of species (and not only in Pterophyllum), results in<br />

a rough but by no means definitive picture, so I will largely refrain from systematic arguments—<br />

they would be beyond the scope of this article and would contribute nothing new.<br />

When I was a young boy, it was enough to know that my angelfishes sailed through life with<br />

the scientific name Pterophyllum scalare. I was also immensely proud of being able to pronounce<br />

the name correctly (TAIR-oh-FY-lum skuh-LAR-ee). Even the discovery that there was another,<br />

smaller species, Pterophyllum eimekei, didn’t particularly bother me; very soon it<br />

was thought these two forms couldn’t be separated. They were merrily crossed<br />

with each other, even in the absence of imports.<br />

Veiltail, Smoke, and Ghost<br />

As it turns out, angels have a high potential for changes in<br />

finnage and coloration. The first Veiltail <strong>Angels</strong>, which<br />

came from a breeder in Gera (Thüringen),<br />

have probably passed into oblivion<br />

today—heaven be praised! Veiltail<br />

<strong>Angels</strong> brought their breeders a<br />

good price, since nobody cared<br />

about things like deformity in<br />

those days. Black <strong>Angels</strong> followed,<br />

but these soon showed not inconsiderable<br />

signs of degeneration. And the<br />

same was true of a series of black versions<br />

of other species. In Hoplosternum,<br />

for instance, black specimens were regularly<br />

blind. It was also not uncommon for<br />

pure black specimens to be infertile.<br />

Crosses between the Black Angel and the<br />

original form produced Smoke <strong>Angels</strong>. People<br />

repeatedly resorted to these Smoke <strong>Angels</strong> in<br />

order to avoid deformed specimens or completely<br />

unviable embryos.

H.-G. EVERS<br />

During a trip with Dr. Hans-Joachim Franke to what was then Czechoslovakia, at the end of<br />

the 1960s, we discovered the Marbled Angel at a friend’s house. Jochen brought some back, as<br />

he made his living from breeding fishes, and they sold well. I didn’t get involved—I didn’t think<br />

these cultivated forms could ever compare with the wild forms.<br />

Soon thereafter, Franke crossed the Marbled Angel into the Black Angel, so as to revitalize the<br />

Black strain in this way. That is the reason why, when you breed with Black <strong>Angels</strong> nowadays,<br />

there are always Golden <strong>Angels</strong> among the offspring. They probably all go back to this strain. In<br />

those days, homozygous strains—that is, fishes that breed true—were regarded as an expensive<br />

luxury, but that was the only way to obtain 100 percent black individuals.<br />

But the development of cultivated forms continued unabated. The potential was far from<br />

exhausted: Ghost <strong>Angels</strong>, Zebra <strong>Angels</strong>, Half-Moon <strong>Angels</strong>, White <strong>Angels</strong> (so-called “White<br />

Pearl”), Blue <strong>Angels</strong> (apparently a back-cross with White Pearl, as they sometimes exhibited<br />

the same changes in scalation), and Red <strong>Angels</strong>. The Red <strong>Angels</strong> came about<br />

through intensive breeding work by Frank Wilhelm in Kamsdorf (Thüringen),<br />

who used long-term selective breeding to produce Koi <strong>Angels</strong><br />

and “Red Devils” from the Marbled Angel. He even obtained pure<br />

red specimens, although he was only partially successful in fixing<br />

the red color on the belly region of the fishes.<br />

Mass production<br />

Ever since people started keeping fishes for aesthetic reasons, they have<br />

disagreed about what makes an attractive cultivated form. A “Red Devil”<br />

can be a real sight for sore eyes, but “can” is the operative word. Many<br />

of the fishes sold as angels in the pet trade today have had their wings<br />

severely clipped. Their form is only vaguely reminiscent of the unique<br />

original fish. Dorsal and anal fins are mere stumps, the ventral fins often<br />

often twisted like corkscrews. The colors and markings of these fishes<br />

are faded and washed out.<br />

The cause of this is usually rearing under cramped conditions and/<br />

or an unbalanced diet. Infrequent or insufficient water changing is usually<br />

involved as well. This type of “mass production” never produces optimal<br />

specimens. Many other fish species likewise fail to thrive under such inadequate<br />

rearing conditions, a few as badly as angels. It also takes several genera-<br />

Below: On the<br />

rear half of the<br />

body, this form still<br />

has the “Smoke”<br />

component, a<br />

formerly popular<br />

cultivated form.<br />

AMAZONAS 35

AMAZONAS<br />

36<br />

tions to produce good fishes from<br />

such degenerate stock. Deformity of the ventral fins almost always indicates artificial rearing<br />

and the use of Trypaflavine (Acriflavine). This fungicide, frequently used as a medication for<br />

certain diseases in our fishes, is a mitosis toxin—in other words, it prevents cell division and<br />

thus causes damage during development of the embryo. In addition, it is classed as a carcinogen<br />

because of this property and<br />

may not be used as a medication<br />

in the production of food fishes.<br />

If angelfishes are to be reared<br />

artificially—and a professional<br />

fish breeder quite simply has<br />

to do it that way—then methylene<br />

blue should be used. It is<br />

a relatively mild oxidant and<br />

causes no damage when used at<br />

light-blue levels.<br />

Of course, the crowning<br />

achievement is to have angels<br />

practice brood care. But that<br />

doesn’t always happen right<br />

from the start. The prerequisite<br />

is a fully compatible pair that<br />

has formed from a group. If the<br />

aquarium is large enough and<br />

well arranged, the rest of the<br />

group can generally remain in<br />

the tank. This will serve to stimulate<br />

the brood-care instinct of<br />

the pair. Naturally, such broods<br />

are blessed with far fewer fry, but<br />

the sight is more than adequate<br />

compensation.<br />

Peruvian Altums<br />

Over the decades, numerous,<br />

mostly wild-caught populations<br />

have passed through my tanks.<br />

I have had some strange experiences<br />

with the so-called Peruvian<br />

Altum from the Río Nanay. They<br />

Above, left: <strong>Angels</strong> are<br />

bred in the thousands<br />

by large breeding<br />

enterprises like this one<br />

in Asia.<br />

Above, right: This<br />

Half-Black Angel<br />

(upper corner of tank)<br />

at a breeding farm in<br />

Singapore is diligently<br />

tending its young,<br />

despite the low water<br />

level, and attacked<br />

the approaching<br />

photographer. This<br />

demonstrates that the<br />

brood-care instinct<br />

is generally retained,<br />

even in professional<br />

hatcheries.<br />

Left: Old male Peruvian<br />

Altum. Unfortunately,<br />

the red-brown dots on<br />

the body have been<br />

obliterated by the<br />

camera flash.<br />

TOP: H.-G. EVERS; BOTTOM: H.J. AUGUSTIN

MIDDLE: H.J. AUGUSTIN; OTHERS: H.-G. EVERS<br />

Tank-bred offspring<br />

of my Red-Back<br />

<strong>Angels</strong>. These fish<br />

need lots of space,<br />

plenty of food,<br />

and good water if<br />

they are to grow<br />

into such splendid<br />

specimens.<br />

Right: Red-Back<br />

<strong>Angels</strong> from the<br />

Manacapuru<br />

spawning on a<br />

suspended plastic<br />

tube.<br />

Below: Group of<br />

“Red Devils”, an<br />

intense red-orange<br />

cultivated form<br />

developed from the<br />

Koi Angel.<br />

are named for their steep upper head profile,<br />

although they have nothing to do with the<br />

Pterophyllum altum found in Venezuela and<br />

Colombia. I selected a number of specimens<br />

from an import consignment and soon had<br />

young. Then suddenly, in the second brood,<br />

four youngsters turned up with a fleshcolored<br />

to reddish base color, interrupted<br />

only by a few rather small black markings.<br />

The eyes were dark, so they weren’t albinos,<br />

but probably xanthic specimens. All four<br />

were females. They were hardly full-grown<br />

before the black speckles developed into very<br />

obvious tumors, and the fishes died within<br />

a short time. No other brood ever produced<br />

specimens like this.<br />

AMAZONAS 37

AMAZONAS<br />

38<br />

Unfortunately, the tank-breds became increasingly<br />

more aggressive, and specimens acquired from aquarists<br />

who had obtained them from me as youngsters brought<br />

no improvement. When the male killed the female even<br />

in a 6.5-foot (2-m) aquarium, I finally decided to give up.<br />

Red-Back <strong>Angels</strong><br />

I had high hopes of a new strain: Red-Back <strong>Angels</strong> from<br />

Manacapuru. It was incomprehensible that such a gorgeous<br />

fish could have remained unnoticed for so long<br />

by collectors so close to Manaus. The fish were not only<br />

gorgeous, but without doubt the most peaceful angels<br />

ever to swim in my tanks. I kept a group of 11 individuals<br />

in a 210-gallon (800-L) aquarium, with a few Ancistrus<br />

looking after the bottom region.<br />

It happened that three pairs spawned simultaneously<br />

on plastic tubes suspended in the tank no more than a<br />

foot (30 cm) apart. All the pairs were shepherding their<br />

broods, and I even observed fry leaving their own parents<br />

and swapping broods.<br />

I find it remarkable that these Manacapuru <strong>Angels</strong><br />

apparently don’t live to be as old as those from other<br />

strains. After just two or three years they already showed<br />

signs of aging, and the intervals between spawns became<br />

increasingly longer. Unfortunately this strain is also<br />

becoming less common. I had hoped that such splendid<br />

fish wouldn’t disappear through crossing into the general<br />

mish-mash, but I am already seeing “Manacapuru<br />

<strong>Angels</strong>” that are no such thing on sale in many places.<br />

The reason is probably the lack of patience common in<br />

breeders; these fish aren’t easy. They have a particular<br />

need for lots of rearing space, if you want to rear attractive,<br />

high-backed specimens.<br />

Surinam Altums<br />

Some years ago, a form of angelfish with red-brown spots<br />

arrived from Surinam. They were termed Surinam Altum<br />

“Red Spotted”. These splendid angels with blue-violet<br />

fins had nothing to do with Altums, although growing<br />

juveniles looked very similar. But how did they get to Surinam?<br />

Arend van den Nieuwenhuizen told me that once<br />

upon a time, a consignment of fishes was left stranded<br />

in the capital, Paramaribo, after a plane from Manaus<br />

stopped off there. Out of pity for the fishes, the entire<br />

consignment was tipped into a lake near the airport,<br />

where there are now said to be Cardinal Tetras and angelfishes.<br />

Could the fish in my aquariums be those?<br />

Wherever they came from, they are beautiful fish, although<br />

initially they presented huge problems. Individual<br />

wild specimens kept suffering dreadful breakouts on the<br />

head and below the dorsal fin. The best solution was to<br />

paint these areas with potassium permanganate, although<br />

the cure was only temporary. A number of juveniles from<br />

the first brood also died of this strange plague. But after<br />

that the disease appeared to have been conquered.<br />