Bog moss (Mayaca fluviatilis Aubl.) - Department of Primary Industries

Bog moss (Mayaca fluviatilis Aubl.) - Department of Primary Industries

Bog moss (Mayaca fluviatilis Aubl.) - Department of Primary Industries

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PR10_5089<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Employment, Economic Development and Innovation<br />

Biosecurity Queensland<br />

Steve Csurhes and Clare Hankamer—April 2010<br />

Note: Information is still being collected for this<br />

species. Technical comments on this document<br />

are most welcome.<br />

Tomorrow’s Queensland: strong, green, smart, healthy and fair<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t<br />

B o g m o s s<br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.

© The State <strong>of</strong> Queensland, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Employment, Economic Development and<br />

Innovation, 2010.<br />

Except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, no part <strong>of</strong> the work may in any form or by any<br />

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any other means be reproduced, stored<br />

in a retrieval system or be broadcast or transmitted without the prior written permission <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Employment, Economic Development and Innovation. The information<br />

contained herein is subject to change without notice. The copyright owner shall not be liable<br />

for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks<br />

and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or<br />

indirectly from using this information.<br />

Enquiries about reproduction, including downloading or printing the web version, should be<br />

directed to ipcu@deedi.qld.gov.au or telephone +61 7 3225 1398.<br />

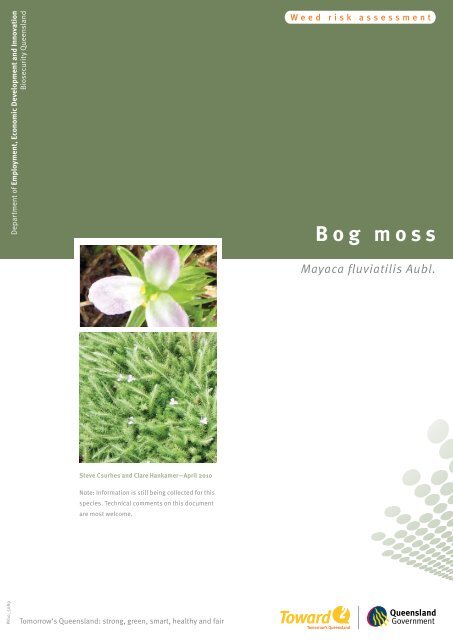

Front cover: <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> near Innisfail, North Queensland<br />

(Photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie Goodall, DERM - used with permission).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

2

Contents<br />

Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4<br />

Identity and taxonomy ........................................................................................................ 5<br />

Description ......................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Reproduction and dispersal ...............................................................................................10<br />

Native range and worldwide distribution ............................................................................ 11<br />

History <strong>of</strong> introduction and spread in Queensland .............................................................. 11<br />

Distribution in Australia .....................................................................................................12<br />

Ecology and preferred habitat ............................................................................................12<br />

History as a weed overseas ................................................................................................14<br />

Current impact in Queensland ............................................................................................14<br />

Potential impact in Queensland .........................................................................................15<br />

Uses ..................................................................................................................................17<br />

Control ..............................................................................................................................17<br />

References .........................................................................................................................18<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

3

Summary<br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>. (bog <strong>moss</strong>) is a tropical/subtropical aquatic plant native<br />

to Central and South America, the Caribbean and the United States. Under<br />

favourable conditions it can form dense mats that block freshwater ponds,<br />

streams and drainage ditches.<br />

The first naturalised population <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in Queensland was formally<br />

identified near Innisfail in 2008. Prior to this, the plant had been sold as an<br />

aquarium plant for many years.<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is a pest within parts <strong>of</strong> its native range, particularly in Puerto Rico,<br />

Florida and North Carolina.<br />

Dispersal is via broken stem fragments. Seed production has been recorded<br />

overseas. However, specimens grown in aquaria in Queensland are believed to<br />

be sterile.<br />

While the species’ potential impact is difficult to predict, it might smother<br />

and replace native aquatic plant species, block drainage/irrigation ditches on<br />

sugarcane farms, and impede recreational activities such as boating and fishing.<br />

This assessment concludes that M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> poses a high weed risk, based on<br />

the following evidence:<br />

(1) it has a history as a pest within its native range,<br />

(2) it is well adapted to subtropical and tropical climates <strong>of</strong> Queensland, and<br />

(3) experience in North Queensland confirms it can block drainage<br />

infrastructure on sugarcane farms.<br />

Important note:<br />

Please send any additional information, or advice on errors, to the authors.<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

4

Identity and taxonomy<br />

Species: <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

Synonyms:<br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> aubletii Michx.<br />

M. longipes Gand.<br />

M. michauxii Schott & Endl.<br />

M. caroliniana Gand.<br />

M. longipes Gand.<br />

M. vandellii Schott & Endl.<br />

M. wrightii Griseb.<br />

Syena <strong>fluviatilis</strong> Willd.<br />

S. mayaca J.F. Gmel.<br />

S. aubletii Michx in Schott & Endl.<br />

S. nuttaliana Schult.<br />

Common names:<br />

<strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> (US), stream bog <strong>moss</strong> (US), pine tree (New Zealand).<br />

Aquarium/pond trade names:<br />

Green mayaca (and mayaca green), green pine, silver foxtail.<br />

Family: <strong>Mayaca</strong>ceae<br />

The family <strong>Mayaca</strong>ceae comprises a single genus—<strong>Mayaca</strong>. The number <strong>of</strong> species in the genus<br />

is uncertain; some publications state that there are four species (Mabberley 2000; Lourteig<br />

1952), others state there are 10 (Heywood 1998; Thieret 1975) and the Missouri Botanical<br />

Garden’s Tropicos database (Tropicos 2010) lists 12 species. The <strong>Mayaca</strong>ceae are found mainly<br />

in the Americas, with one species, <strong>Mayaca</strong> baumii Gürke, in sub-Saharan Africa (Angola).<br />

Subordinate taxa:<br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> forma <strong>fluviatilis</strong><br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> forma kunthii (Seub.) Lourteig<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> var. wrightii (Griseb.) M. Gómez<br />

Related species:<br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> aubletii Michx.<br />

M. baumii Gürke<br />

M. brasillii Hoehne<br />

M. boliviana Rusby<br />

M. curtipes Poulsen, V.A.<br />

M. endlicheri Poepp. Ex Seub.<br />

M. lagoensis Warm.<br />

M. longipedicellata<br />

M. longipes Mart. Ex Seub.<br />

M. madida Vell. (Stellfeld)<br />

M. sellowiana Kunth<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

5

Taxonomic uncertainty:<br />

There is considerable uncertainty regarding the taxonomic relationship between species <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> and between various forms <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong>. Semi-aquatic plants <strong>of</strong>ten have the ability<br />

to produce different types <strong>of</strong> leaves above and below water (a feature known as heterophylly)<br />

(Wells and Pigliucci 2000). Such morphological plasticity is thought to be an adaptation to a<br />

dynamic environment (Wells & Pigliucci 2000; eFloras 2010). For example, M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> and<br />

M. aubletii display subtle differences in morphology, with shorter leaves, longer pedicels and<br />

ovoid to nearly globose capsules evident in M. aubletii and longer leaves, shorter pedicels<br />

and oblong-ellipsoid capsules in M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> (eFloras 2010). Such plasticity has confounded<br />

attempts to classify the species and makes identification difficult.<br />

Description<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is a perennial monocotyledonous plant that can grow either fully submerged,<br />

in the form <strong>of</strong> semi-floating mats, or as a semi-terrestrial plant on the margins <strong>of</strong> wetlands.<br />

It can form very dense mats <strong>of</strong> branching prostrate or erect stems, generally 40–60 cm long<br />

(eFloras 2010), but sometimes well over 1 m (CAIP 2009). Its morphology varies depending<br />

on prevailing conditions (Thieret 1975; eFloras 2010). Submerged specimens tend to have<br />

long trailing stems with spirally arranged leaves that are long-tapering and translucent<br />

(Figure 1); also see online video link (http://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/node/263). They also have a thicker<br />

endodermis and more aerenchyma than emersed forms. Emersed plants tend to have shorter<br />

stems with shorter, thicker closely imbricate leaves (Thieret, 1975); see Figures 2, 3 and 4.<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

6<br />

Figure 1. Submerged stems <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong><br />

<strong>fluviatilis</strong> showing spirally arranged,<br />

long tapering leaves and white stems.<br />

Note: Stem tips are pink in colour<br />

compared with pinkish-red for Rotala<br />

wallichii. The latter has pinkish-purple<br />

flowers arranged in a raceme<br />

(photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie<br />

Goodall, DERM).

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

7<br />

Figure 2. Leaves <strong>of</strong> floating M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong><br />

(photo: Vic Ramey, University <strong>of</strong> Florida/IFAS<br />

Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants).<br />

The leaves are sessile, without a sheath (Mabberley 2000), s<strong>of</strong>t, <strong>moss</strong>-like and thread-like,<br />

arranged densely in a spiral around the stem. Leaves are not divided like those <strong>of</strong> Egeria<br />

densa (CAIP 2009) or Myriophyllum aquaticum. Leaf blades are narrowly lanceolate to linear,<br />

2–30 mm × 0.5 mm, and the apex entire or notched (Heywood 1998; eFloras 2010).<br />

Flowers are up to 10 mm wide, bisexual, borne singly on pedicels 2–12 mm long and<br />

subtended by membranous bracts, which usually become reflexed after flowering (Heywood<br />

1998; eFloras 2010). Flowers are terminal, but appear to be axillary due to the sympodial<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> the stem (Mabberley 2000; Philipps 2010).<br />

Figure 3. <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in flower (photo: Tom Philipps, USDA Forest Service).

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

8<br />

Figure 4. Flower <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong>—Taree,<br />

New South Wales<br />

(photo: Peter Harper).<br />

The perianth is arranged in two whorls: the outer sepal-like with three elongate segments that<br />

persist in fruit, the inner petal-like with three whitish pink to violet or even maroon segments<br />

(Heywood 1998). The sepals are ovate to lanceolate-elliptic, 2–4.5 mm x 0.7–1.5 mm; petals,<br />

sometimes whitish basally, are also broadly ovate, 3.5–5 mm × 3–4.5 mm (eFloras 2010).<br />

The three stamens (1.5–3 mm in length) are alternate with petal-like segments; filaments<br />

are 1–2 mm; anthers are 0.5–1 mm, dehiscing by means <strong>of</strong> apical, pore-like slits (Heywood<br />

1998; eFloras 2010). The ovary is superior and composed <strong>of</strong> three fused carpels, forming<br />

a single locule containing numerous orthotropous ovules attached in two rows to three<br />

pariental placentas (Heywood 1998). The fruit is a three-valved capsule that is nearly globose<br />

to ellipsoid, <strong>of</strong>ten irregular because <strong>of</strong> abortion, to 4 mm × 3.4 mm (Heywood 1998; eFloras<br />

2010). There are 2–25 seeds per capsule. Seeds are nearly globose, 1.3 mm × 0.9 mm. The<br />

seed coat is ridged and pitted (eFloras 2010).

Figure 5. Solitary <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> flowers showing long pedicels<br />

(photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie Goodall, DERM).<br />

The seeds <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> species are characterised by the presence <strong>of</strong> an embryostegium or<br />

‘stopper’ at the micropylar end, which seems to develop from the inner integument. The<br />

disintegration <strong>of</strong> this ‘stopper’ is thought to provide a canal for the emergence <strong>of</strong> the seedling<br />

(Thieret 1975).<br />

Figure 6. Seeds <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> (photo: Jose Hernandez @ USDA–NRCS PLANTS Database).<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> can initially grow as a fully submerged plant, rapidly forming numerous stems.<br />

Once these stems reach the water surface, they spread out, forming a dense mat <strong>of</strong> shorter<br />

branches (Figure 7).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

9

Figure 7. Mats <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in a drainage channel near Innisfail<br />

(photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie Goodall, DERM).<br />

A helpful video on the identification <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong>, prepared by the Center for Aquatic and<br />

Invasive Plants, University <strong>of</strong> Florida, IFAS, is available at http://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/node/263<br />

Reproduction and dispersal<br />

In the southern United States, where M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is native, flowering occurs from March to<br />

November, but typically May to October (Philipps 2010).<br />

Seeds are probably dispersed by water (Thieret 1975). Ludwig (1886) found that seeds<br />

dried for six weeks germinated in water more rapidly than those that had been continuously<br />

submerged for the same period. This second group did not germinate even after 12 weeks<br />

submerged.<br />

Plants sold in the commercial aquarium plant trade are thought to be sterile due to selection<br />

<strong>of</strong> clonal stock over long periods <strong>of</strong> time (E Frazer, Pisces Aquarium Plants, pers. comm.,<br />

March 2010).<br />

Yakandawala (2009) found that stem fragments as small as 2 cm long could produce new<br />

roots and shoots. Hence, mechanical removal or other physical disturbance has the potential<br />

to dramatically increase rate <strong>of</strong> spread.<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

10

Native range and worldwide distribution<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is native to Central and South America, the Caribbean and the US.<br />

Tropicos (2010), USDA (2010) and GRIN (2010) list herbarium collections from the following<br />

countries:<br />

• Central and South America—Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica,<br />

Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama,<br />

Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay and Venezuela<br />

• Caribbean—Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago<br />

• US—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina,<br />

Texas and Virginia.<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> has naturalised in Sri Lanka (Yakandawala 2009) and Singapore (Aquatic<br />

Quotient 2005).<br />

History <strong>of</strong> introduction and spread in<br />

Queensland<br />

Naturalised M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> was first recorded in Queensland in shallow flowing water within a<br />

table drain at Silkwood, near Innisfail in 2008 (Figure 8) (A. Reilly, Qld DERM, pers. comm.,<br />

March 2010). The source <strong>of</strong> the infestation was an overflow drain from nearby aquaculture<br />

ponds. M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> was being sold as an aquarium plant. It has been speculated that the<br />

plant may have originally entered the watercourse some time in 2006.<br />

Figure 8. M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> growing immediately downstream <strong>of</strong> its suspected origin, near Innisfail<br />

(photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie Goodall, DERM).<br />

In April 2010, plant material tentatively identified as M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> was detected near Mareeba<br />

and near Mossman. Specimens were sent to the Queensland herbarium for identification but<br />

may be Myriophyllum spp. (K. Stephens, Qld herbarium, pers. comm., March 2010).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

11

Distribution in Australia<br />

Outside Queensland, naturalised M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> has only been detected at a single site near<br />

Taree (New South Wales) in 2008 (North Coast Weed Read 2008; Asia Pacific Weed Service<br />

Newsletter 2008); see Figure 9.<br />

Figure 9. <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in a pond near Taree, northern New South Wales<br />

(photo: Peter Harper).<br />

Ecology and preferred habitat<br />

Climatically, M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is well suited to tropical and subtropical areas. Within these climate<br />

zones it is best adapted to freshwater aquatic habitats, namely shallow wetlands, seepage<br />

areas and the margins <strong>of</strong> lakes, ponds and rivers (CAIP 2009; Heywood 1998; Philipps 2010).<br />

These sites experience fluctuations in water level, with periodic inundation during floods and<br />

short-term desiccation during the dry season (USDA 2010; FLUCCS n.d.).<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> can tolerate water 1–2 m deep (North Carolina <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Environment and<br />

Natural Resources, 2006). Some authors describe the plant as ‘amphibious’, since it can grow<br />

below and above water (Champion & Clayton 2000; de Carvalho et al. 2009), whereas others<br />

state that it is an obligate submerged plant (Champion & Clayton 2001; FLUCCS n.d.).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

12

This study was unable to find detailed information on environmental variables that define<br />

this species’ preferred habitats. In Florida, M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is typically found in lakes with a low<br />

pH and low levels <strong>of</strong> phosphorous and nitrogen. Philipps (2010) categorised its preferred<br />

habitat as waterways with high acidity and high levels <strong>of</strong> organic matter. Venero Camaripano<br />

and Castillo (2003) found M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in flooded forest at altitudes <strong>of</strong> 0–1200 m in Sipapo,<br />

Venezuela. Visual observation <strong>of</strong> the species in Queensland and New South Wales suggests it<br />

prefers open waterbodies (full sun) and perhaps disturbed sites.<br />

Experienced growers <strong>of</strong> aquarium plants comment that M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is ‘self-smothering’<br />

in aquaria, becoming brittle and dying <strong>of</strong>f after rapidly depleting soluble carbon dioxide,<br />

reducing water circulation and lowering pH (resulting in iron deficiency). Like many aquatic<br />

plants, M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> grows in phases or ‘flushes’, depending on the suitability <strong>of</strong> prevailing<br />

environmental conditions (E Frazer, pers. comm., March 2010). There is little information on<br />

its growth requirements in situ; however, temperature requirements ex situ in an aquarium<br />

environment are reported in the range <strong>of</strong> 20–30 ˚C.<br />

Figure 10. Areas <strong>of</strong> Australia where climate appears suitable for survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong>. This<br />

model was generated using ‘Climatch’ climate-matching computer program and was based on global<br />

distribution data for the species. Blue and green indicate areas where climate is considered unsuitable<br />

for this species, yellow and orange indicate areas where climate is marginally suitable and red<br />

indicates areas where climate is highly suitable (map by Martin Hannan-Jones).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

13

History as a weed overseas<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is listed as a noxious weed in Puerto Rico and is subject to control activity in<br />

Florida and North Carolina. These locations are all within the species’ native range. In Florida,<br />

it blocks freshwater lakes and is subject to periodic control action to allow recreational<br />

activities (fishing and boating) (GCW 2007; GRIN 2010; Hanlon et al. 2000; North Carolina<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Environment and Natural Resources 2006).<br />

Yakandawala (2009) expressed concern at the invasive potential <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in Sri Lanka,<br />

where it has naturalised in two waterbodies. An online forum for aquarium enthusiasts<br />

states that M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> has naturalised in Singapore (MacRitchie Reservoir) in 2005 (Aquatic<br />

Quotient 2005).<br />

This study was unable to find data on the species’ economic impacts elsewhere.<br />

Current impact in Queensland<br />

Currently, the impact <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> is negligible in Queensland, since it is restricted to a<br />

small infestation near Innisfail. At one point in time, this infestation had blocked 1.5 km <strong>of</strong><br />

table drain (Figure 11). Subsequent damage to a culvert and section <strong>of</strong> road during heavy rain<br />

was blamed on blockage by M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong>. The infestation was mechanically removed by a<br />

local drainage board (A Reilly pers. comm., March 2010). However, by December 2008 it had<br />

grown back to infest 2.5 km <strong>of</strong> the same drain. Soon after, flooding washed large amounts <strong>of</strong><br />

plant material downstream, possibly including the river catchments for Maria Creek National<br />

Park. There is concern that it may have spread into Liverpool Creek and the Kurrimine Beach<br />

Wetland Aggregation and National Park (Weed Spotters Queensland Network 2009).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

14<br />

Figure 11. Table drain blocked by <strong>Mayaca</strong><br />

<strong>fluviatilis</strong> alongside sugarcane near<br />

Innisfail<br />

(photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie Goodall,<br />

DERM).

Potential impact in Queensland<br />

Prolific growth <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> could block drains, irrigation infrastructure, freshwater lakes,<br />

ponds and streams, in much the same way as a range <strong>of</strong> other widespread aquatic weed<br />

species. Blocked drains increase waterlogging problems in adjacent crops and can cause<br />

greatly reduced yields. Large mats that break free during floods could cause significant damage<br />

to bridges and moored boats. Experience from New South Wales suggests that dense growth<br />

<strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> can pose a threat to human safety since swimmers are unable to break through<br />

the mats from underneath and could become entangled (P Harper pers. comm., March 2010);<br />

see Figures 12 and 13. As has occurred in the US, dense mats can impede recreational activities<br />

such as fishing and boating. Such growth needs to be removed on a regular basis, thereby<br />

generating ongoing costs for government and other water management agencies. Uncontrolled<br />

growth might have localised impacts on tourism, if recreation is hindered.<br />

Figure 12. Dense growth <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> can block waterways and impede recreational activity such as<br />

boating and fishing—photo taken near Taree, New South Wales (photo: Peter Harper).<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

15

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

16<br />

Figure 13. Dry mat <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong><br />

<strong>fluviatilis</strong><br />

(photo: Audrey Reilly and Kylie<br />

Goodall, DERM).<br />

The impact <strong>of</strong> M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> on native aquatic ecosystems is difficult to predict. However, it<br />

might compete with certain native aquatic plants, especially in disturbed sites. It seems<br />

reasonable to be concerned that, under favourable conditions, M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> could form dense<br />

mats that exclude most other plant life.<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> could potentially occupy the same niche as several species <strong>of</strong> native<br />

Myriophyllum. Two species <strong>of</strong> Myriophyllum are listed as threatened in Queensland: M.<br />

artesium (endangered) and M. coronatum (vulnerable), as defined by Queensland’s Nature<br />

Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006. M. artesium exists in spring wetlands in Barcaldine<br />

and Eulo and M. coronatum exists only in Lake Bronto, Cape York.

Uses<br />

M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> has been sold as an aquarium plant possibly since the early 1900s. It is valued<br />

for its attractive foliage and stems but can be difficult to maintain, requiring high light<br />

levels, additional carbon dioxide and fertiliser (‘The stemmed plants’ 2006). Current sales in<br />

Queensland are estimated to be less than 1% <strong>of</strong> the total market for aquarium plants (E Frazer,<br />

pers. comm., March 2010). Although, quite popular in Australia some years ago, its popularity<br />

has declined over the last few years.<br />

Control<br />

Mechanical control is <strong>of</strong>ten used to clear aquatic plant infestations. However, there is a high<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> spread associated with any method that causes fragmentation <strong>of</strong> stems (Gettys et al.<br />

2009).<br />

In Florida, sterile triploid grass carp have been used to control various aquatic macrophytes,<br />

including M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong>. Hanlon et al. (2000) reported successful control <strong>of</strong> aquatic<br />

macrophytes after stocking lakes with more than 25–30 grass carp per hectare <strong>of</strong> vegetation.<br />

Notably, control was ineffective if lakes were stocked with fewer fish. In a 55 ha lake, <strong>of</strong> which<br />

40% was covered by with M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong>, weed cover was reduced to zero after four years <strong>of</strong><br />

stocking with grass carp at a rate <strong>of</strong> 18 carp per hectare <strong>of</strong> vegetation (Hanlon et al. 2000).<br />

Herbicide control experiments have been undertaken on M. <strong>fluviatilis</strong> in New South Wales,<br />

but effective treatments have proved elusive.<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

17

References<br />

Aquatic Quotient, 2005, ‘<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> - a new alien in Singapore waters’, online<br />

forum article, viewed 25 June 2010, .<br />

Asian Pacific Weed Service Newsletter April 2008, ‘<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> (bog <strong>moss</strong>): a new<br />

aquatic species found in NSW’, Volume 1, Issue 2.<br />

CAIP 2009, ‘<strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong>’, Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, University <strong>of</strong> Florida, IFAS,<br />

viewed 29 March 2010, .<br />

Champion, PD and Clayton, JS 2000, ‘Border control for potential aquatic weeds: stage 1 –<br />

weed risk model’, Science for Conservation 141, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Conservation, Wellington, New<br />

Zealand.<br />

Champion, PD and Clayton, JS 2001, ‘Border control for potential aquatic weeds: stage 2 – weed<br />

risk assessment’, Science for Conservation 185, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Conservation, Wellington,<br />

New Zealand.<br />

Champion, P, Clayton, J, Burnett, D, Petroeschevsky, A and Newfield, M 2007, ‘Using the New<br />

Zealand Aquatic Weed Risk Assessment Model to manage potential weeds in the ornamental<br />

trade’, International Weed Risk Assessment Workshop (IWRAW), NIWA Taihoro Nukurangi,<br />

NSW <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Industries</strong> and Biosecurity New Zealand, viewed 25 June 2010,<br />

.<br />

de Carvalho, MLS, Nakamura, AT and Sajo, MG 2009, ‘Floral anatomy <strong>of</strong> neotropical species <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Mayaca</strong>ceae’, Flora 204(3): 220–27.<br />

eFloras 2010, ‘Flora <strong>of</strong> North America’, FNA 22, <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong>, viewed 13 April 2010,<br />

.<br />

FLUCCS, 645 Submergent Aquatic Vegetation, Florida Land Use, Land Cover and Forms<br />

Classification System (FLUCCS) Description, .<br />

GBIF 2010, Biodiversity occurrence data, viewed 29 March 2010, .<br />

GCW 2007, Global Compendium <strong>of</strong> Weeds, Hawai’an Ecosystems at Risk (HEAR), <strong>Department</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Forestry, USDA, viewed 29 March 2010, .<br />

Gettys, LA, Haller, WT and Bellaud, M (eds.) 2009, Biology and control <strong>of</strong> aquatic plants: a<br />

best management practices handbook. Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Foundation, Marietta,<br />

Georgia, US.<br />

Govaerts, R (ed.) 2009, ‘World checklist <strong>of</strong> selected plant families’, Royal Botanic Gardens<br />

Kew, UK, viewed 14 April 2010, http://apps.kew.org/wcsp/compilersReviewers.do<br />

GRIN 2010, USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program, Germplasm Resources<br />

Information Network (GRIN), National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland,<br />

viewed 29 March 2010, .<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

18

Hanlon, SG, Hoyer, MV, Cichra, CE and Canfield, DE 2000, ‘Evaluation <strong>of</strong> macrophyte control<br />

in 38 Florida lakes using triploid grass carp’, J. Aquatic Plant Management 38:48–54.<br />

Heywood, VH (ed.) 1998, Flowering plants <strong>of</strong> the world. BT Batsford, London.<br />

Lourteig, A 1952, ‘<strong>Mayaca</strong>eae’, Notulae Systematicae 14:234–248.<br />

Ludwig, F 1886, ‘Ueber durch Austrocknen bedingte Keimfähigkeit der Samen einiger<br />

Wasserpflanzen’, Biol. Centralb 6:299–300.<br />

Mabberley, DJ 2000, The plant book: a portable dictionary <strong>of</strong> the vascular plants, 2nd edition,<br />

Cambridge University Press, UK.<br />

Natural Aquariums, ‘The stemmed plants’, viewed 25 June 2010, .<br />

North Carolina <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Environment and Natural Resources 2006, Total maximum daily<br />

load for aquatic weeds for Rockingham City Lake, Roanoke Rapids Lake, Big Lake, Reedy Creek<br />

Lake and Lake Wakena in North Carolina. Yadkin-Pee-Dee River Basin, Roanoke River Basin and<br />

Neuse River Basin: final report, Division <strong>of</strong> Water Quality, Raleigh, North Carolina, viewed 28<br />

June 2010, .<br />

NSW North Coast Weeds Advisory Committee 2008, ‘New aquatic weed discovered near<br />

Taree’, North Coast Weed Read 16, Autumn, Grafton, NSW.<br />

Philipps, TC 2010, ‘Stream bog<strong>moss</strong> (<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.)’, Plant <strong>of</strong> the Week. USDA Forest<br />

Service Celebrating Wildflowers, viewed 31 March 2010, .<br />

Thieret, JW 1975, ‘The <strong>Mayaca</strong>ceae in the southeastern United States’, J Arnold Arboretum<br />

56:248–255.<br />

Tropicos 2010, Missouri Botanical Garden, viewed 31 March 2010, .<br />

USDA 2010, <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>. stream bog<strong>moss</strong>. Plants Pr<strong>of</strong>ile, Plants Database, Natural<br />

Resources Conservation Service, USDA, viewed 21 April 2010, .<br />

Venero Camaripano, B and Castillo, H 2003, ‘Catalogue <strong>of</strong> spermatophytes <strong>of</strong> the seasonally<br />

flooded forests <strong>of</strong> Sipapo River, Estado amazonas, Venezuela’, Acta Botánica. Venezuelica<br />

26(2), .<br />

Weed Spotters Queensland Network 2009, ‘A new aquatic weed in north Queensland: <strong>Mayaca</strong><br />

<strong>fluviatilis</strong>, bog <strong>moss</strong>’, Weed Spotters Queensland Network: protecting our future today,<br />

Autumn edition.<br />

Wells, CL and Pigliucci, M 2000, ‘Adaptive phenotypic plasticity: the case <strong>of</strong> heterophylly in<br />

aquatic plants’, Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 3(1):1–18.<br />

Yakandawala, K 2009, ‘<strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.: an ornamental aquatic plant with invasive<br />

species potential in Sri Lanka’. Aquatic weeds. Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the 12th European Weed<br />

Research Society Symposium, August 24–28 Jyväskylä, Finland, Reports <strong>of</strong> the Finnish<br />

Environment Institute 15:108.<br />

W e e d r i s k a s s e s s m e n t : <strong>Bog</strong> <strong>moss</strong> <strong>Mayaca</strong> <strong>fluviatilis</strong> <strong>Aubl</strong>.<br />

19