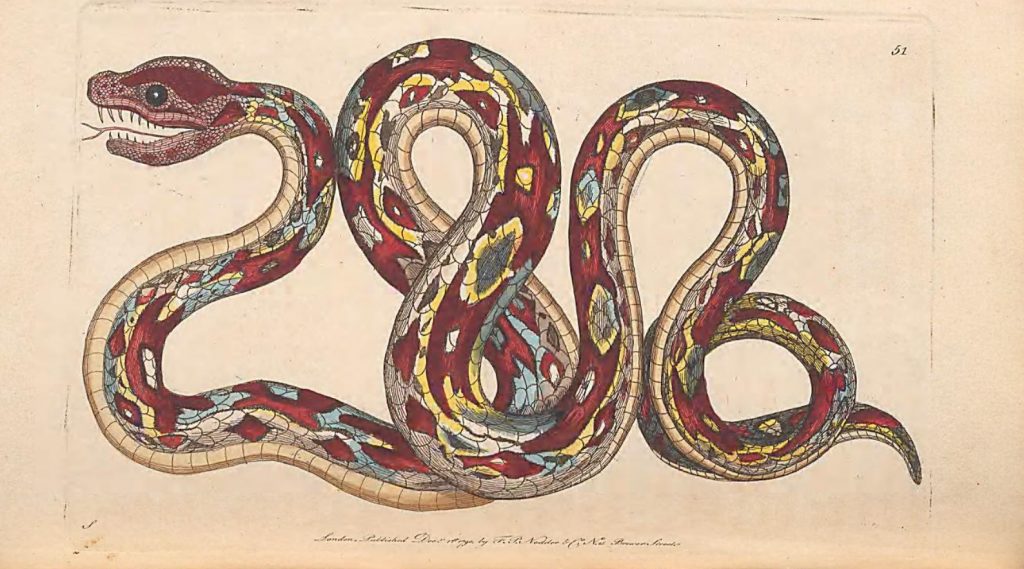

Scientific Name Boa constrictor Boa constrictor, Trinidad. Photo William Montgomery Boa constrictor by Shaw & Nodder, 1791. Described and named by Carl Linne (1707-1778). Better known as Linnaeus, he was responsible for inventing the system we use today to name, rank and classify living organisms. Holotype Hidden inventory / lost, two syntypes, NRM 10 and NRM 20001.

Type Locality ‘‘Indiis’’ in error

Synonyms Boiguacu 42 ]Boiguacu 240 ]Boiguacu 326 ]Vipera americana tab. 746 ]Serpens americana, maximo in honare, etc .tab. 36 ]Serpens americana, arborea, singulari artificio picta, magni aestimata tab. 53 ] (special artifice painted, highly regarded Serpens ammodites Surinamensis tab. 78 ]Cenchris scutis abdominalibus tab II ]Serpens americana arborea, singulari artificio picta, magni aestimata Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor 374 ]Boa contortrix Constrictor formosissimus Constrictor rex serpentum 108 ]Constrictor auspex Constrictor diviniloquus 109 ]Boa constrictor 147 ] [148 ]Boa contortrix 145 ]Boa constrictor Constrictor formosissimus Constrictor rex serpentum Constrictor auspex Boa contortrix Boa constrictor Boa divinatrix 129 ]Boa constrictor Boa constrictor 161 ] [162 ] [163 ]Boa constrictor 6 ] [pl. 5 ]Boa constrictor 38 ] [39 ] [40 ] [41 ] [tab I ]Boa contortrix Boa constrictor 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [pl. 51 ]Boa constrictrix 159 ]Boa divinatrix 181 ]Boa constrictor 52 ]Boa constrictrix 248 ] (unjustified emendation)Boa constrictor 338 ] [339 ] [340 ] [341 ] [342 ] [343 ] [Tab 92 ] [Tab 93 ]Boa constrictor 38 ] [39 ] [40 ] [41 ]Boa constrictor 212 ] [213 ] [214 ] [215 ] [216 ] [217 ] [218 ]Boa constrictor 374 ] [375 ] [376 ] [377 ] [378 ] [379 ] [380 ]Boa constrictor 238 ] [fig 51 ]Boa contortrix 233 ]Constrictor rex serpentum 239 ]Constrictor auspex Boa constrictor Boa constrictor 198 ] [199 ] [200 ] [201 ] [Tab ]Boa constrictor Boa constrictor 508 ] [509 ] [510 ] [511 ] [512 ] [513 ] [514 ] [515 ]Boa diviniloqua 516 ] [517 ] [518 ] [519 ]Boa constrictor Boa constrictor 326 ]Boa constrictor 403 ] [404 ] [405 ] [406 ] [407 ] [408 ]Boa constrictor Boa constrictor pl. III ]Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa diviniloqua Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor 104 ] [105 ] [106 ] [107 ] [108 ] [109 ] [360 ]Boa constrictor 27 ]Constrictor constrictor 320 ] [321 ]Constrictor constrictor Constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor Constrictor constrictor constrictor Constrictor constrictor constrictor Constrictor constrictor constrictor Constrictor constrictor constrictor 404 ]Constrictor constrictor constrictor 19 ] [pl. III ]Boa constrictor constrictor p199 ]Constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor constrictor 52 ]Boa constrictor constrictor 55 ] [56 ]Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor melanogaster Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Starace, 1998: 90Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Tipton, 2005: 39Boa constrictor Binder and Lamp, 2007:Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Boa constrictor Murphy & Crutchfield, 2019: 190 [191]Boa constrictor constrictor Boa constrictor Thorpe & Malhotra, 2023: 1-14The name Boa is derived from the Latin for "large snake", mentioned in Pliny the Elder's Natural History. Subspecies Common Name Common boa, Boa constrictor, the local name for this snake on Trinidad is Macajuel or Macaeouile and on Tobago it’s called Jumbo Jocko .

Description and taxonomic notes Boa constrictor is a heavy bodied, muscular snake. While unsubstantiated stories of extremely large individuals of Boa constrictor continue to be told, most of these are often based in approximations from encounters in the wild. Aside from the difficulties of approximating snakes lengths accurately, there might also be deliberate exaggerations by the story teller. Today and in the recent past, there are few cases where living specimens exceeding 3m in length have been seen or even collected in the wild.

According to Bonny, the largest specimen collected from Trinidad and Tobago had a total length of 335 cm The ordinary length is about eight or nine feet (2.43m-2.74m), but I have had in my cages two which were twelve feet (3.66m) long. Mr. E. L. Mirus, a Trinidad surveyor, assures me that he has seen one fourteen feet (4.27m) long. ” We have frequently seen them 6, 8, and 10 feet, and one in our possession now, which came from Chaguaramas, and the dimensions of which were taken the day after its purchase, measured from tip of nose to extremity of tail 10 feet 6 inches (3.2 meters), but it is probable that it is at least 6 inches longer (total = 3.35 m), as the difficulty of getting it to remain quiet was very great, and it could not be pulled out straight. It was 15 inches (38.1 cm) in circumference at the thickest part of the body. Its head measured 4 inches long ; the circumference of the head at the widest part was 5 inches ; the tail from anus to tip was 11.1 inches; and it weighed 50 lbs (=22.68 kg). exactly. It is probable that Boas (in Trinidad, at any rate) never exceed 12 feet ”

Note that twenty years later Mole contradicted his own statement that boas never exceed 12 feet. Considering literature and captive specimens, it appears conceivable that snakes of more than 3 meters can be found on the islands, even though, as stated about 100 years ago, these were even then the exception rather than the rule. The average size (8-9 feet) stated by Mole seems in line with today’s observations.

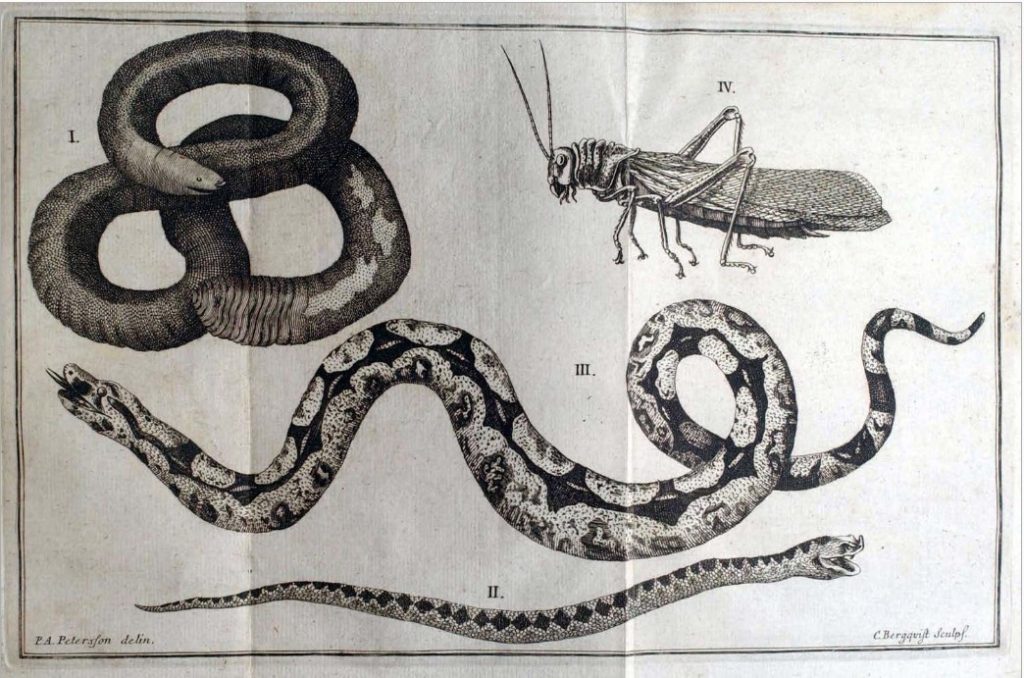

A collaboration between Sundius & Linnaeus produced this very early drawing of Boa constrictor

Boa constrictor, Surinam. Sundius & Linnaeus, 1748. Porras reported the most extreme sizes of Boa constrictor from specimens imported from Peru; he stated that he saw a Boa constrictor “well over 16 feet ” (4787 mm) at the facilities of Bill Chase, an importer from Miami

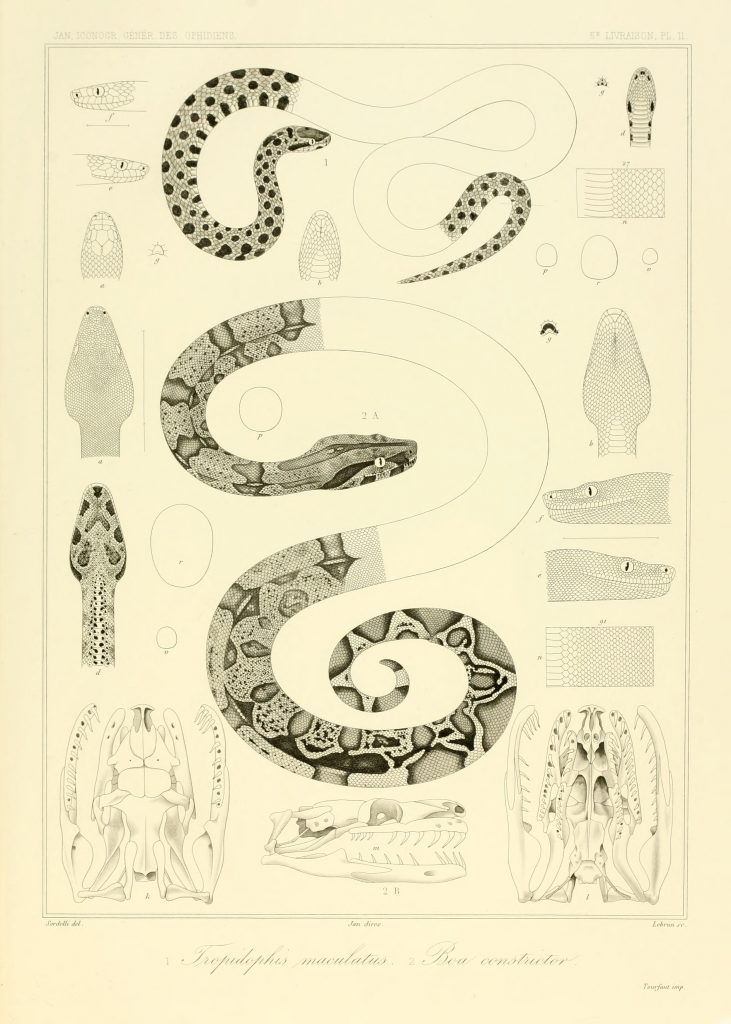

Boa constrictor by Jan, 1864. Distribution Boa constrictor constrictor has a wide distribution on the South American continent including the countries Bolivia, Brazil, Columbia, Ecuador, French Guyana, Guyana, Peru, Surinam and Venezuela. Within the region of the West Indies, this subspecies occurs naturally only on the Islands of Trinidad and Tobago, where Boa constrictor reaches its northernmost natural distribution. Mole as well as Boos recorded Boa constrictor from Trinidad as well as from Tobago

Surprisingly, Mertens did not mention Boa constrictor in his initial article about the Tobago herpetofauna Boa constrictor from Tobago in 1916 Boa constrictor in his Herpetofauna tobagana Boa constrictor only from the two islands: Monos and Gaspar Grande Boa constrictor have been found on Antigua, but no living specimens have been observed. Thus a population of Boa constrictor on Antigua might have existed, but is considered extinct. It is unclear whether this population was of natural origin or brought in by man from other Antillean islands

Trinidad Boa constrictor. Photo William Montgomery In the light of recent taxonomic changes (Boa nebulosa and B. orophias elevated to species level) Boa species which one is the closest living relative. Boa constrictor can survive also further north in the West Indies, as introduced populations of Boa constrictor as well as Boa imperator on several islands of the West Indies have shown. These introduced predators pose a severe threat to the indigenous fauna

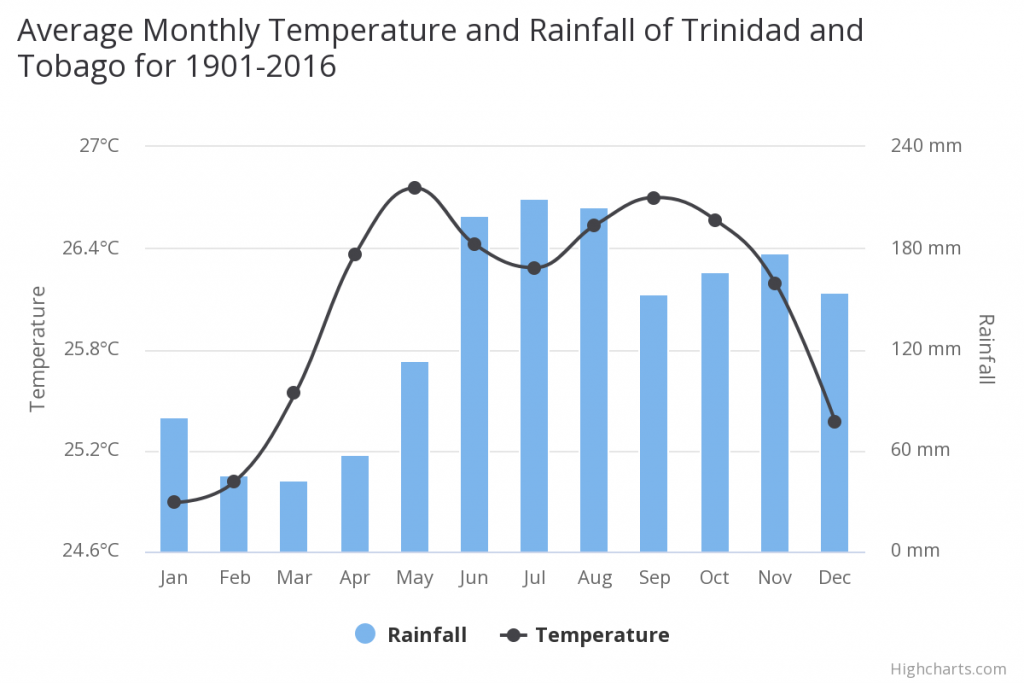

Habitat On Trinidad and Tobago the mean annual temperature is 26.05°C and the m ean annual precipitation is 1604.99 mm. Average rainfall in the north and northeast is 2880 mm and 1200 mm in the west and southwest. The Trinidad weather is tropical and there are only two seasons which can be observed throughout the year: those are the wet season and the dry season. The first six months each year are considered the dry season while the second half would be the wet season with a three week dry spell around September and October. Most of the winds to hit the island come from the northeast. Because of its location Trinidad is usually safe from hurricanes though some in the past have come really close to causing damage. The temperatures are usually very stable in Trinidad.

Trinidad is traversed by three distinct mountain ranges that are a continuation of the Venezuelan coastal cordillera. The Northern Range, an outlier of the Andes Mountains of Venezuela, consists of rugged hills that parallel the coast. This range rises into two peaks. The highest, EI Cerro del Aripo, is 940 meters high; the other, EI Tucuche, reaches 936 meters. The Central Range extends diagonally across the island and is a low-lying range with swampy areas rising to rolling hills; its maximum elevation is 325 meters. The Caroni Plain, composed of alluvial sediment, extends southward, separating the Northern Range and Central Range. The Southern Range consists of a broken line of hills with a maximum elevation of 305 meters.

Boa constrictor from the Northern Ranges, Trinidad. Photo William Montgomery There are numerous rivers and streams on the island of Trinidad; the most significant are the Ortoire River, fifty kilometers long, which extends eastward into the Atlantic, and the forty-kilometer long Caroni River, reaching westward into the Gulf of Paria. Most of the soils of Trinidad are fertile, with the exception of the sandy and unstable terrain found in the southern part of the island. The forest make-up of Trinidad can be classified as lowland moist, degraded lowland moist, submontaine, montane, degraded montane, swamp, mangrove and dry. There are approximately 17 areas consisting of mangroves ranging from 9 ha (Godineau Swamp) to 37.3 km² in the Caroni Swamp

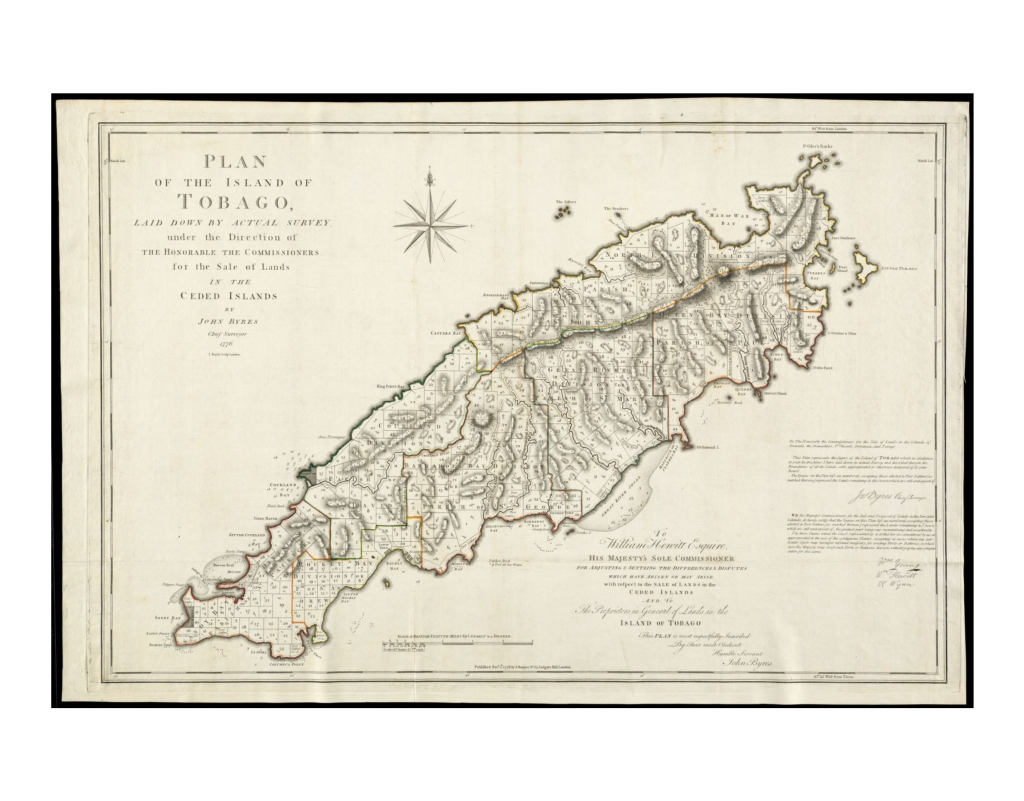

Tobago is mountainous and dominated by the Main Ridge, which is 29 kilometers long with elevations up to 640 meters. There are deep, fertile valleys running north and south of the Main Ridge. The southwestern tip of the island has a coral platform. Although Tobago is volcanic in origin, there are no active volcanoes. Forestation covers 43 percent of the island. There are numerous rivers and streams, but flooding and erosion are less severe than in Trinidad. The coastline is indented with numerous bays, beaches, and narrow coastal plains. Tobago has several small satellite islands. The largest of these, Little Tobago, is starfish shaped, hilly, and consists of 120 hectares of impenetrable vegetation.

We limit our focus to the habitats on Trinidad and Tobago. More general descriptions can be found in the literature. Mohammed and coworkers found Boa constrictor in two different habitat types at their study site in south east Trinidad. These were forest edge and littoral woodland et. al. It is common everywhere in Trinidad, though seldom seen ” Boa constrictor was to be found in woods and damp localities, but not in swamps

In a pilot study of six protected areas in Trinidad and Tobago (these are the Caroni and Nariva Swamps, Matura Forest, Trinity Hills, Main Ridge Forest Reserve and the (proposed) Northeast Tobago Marine Protected Area (NETMPA), Boa constrictor could be found only in two, the Trinity Hills on Trinidad and the Main Ridge Forest Reserve on Tobago

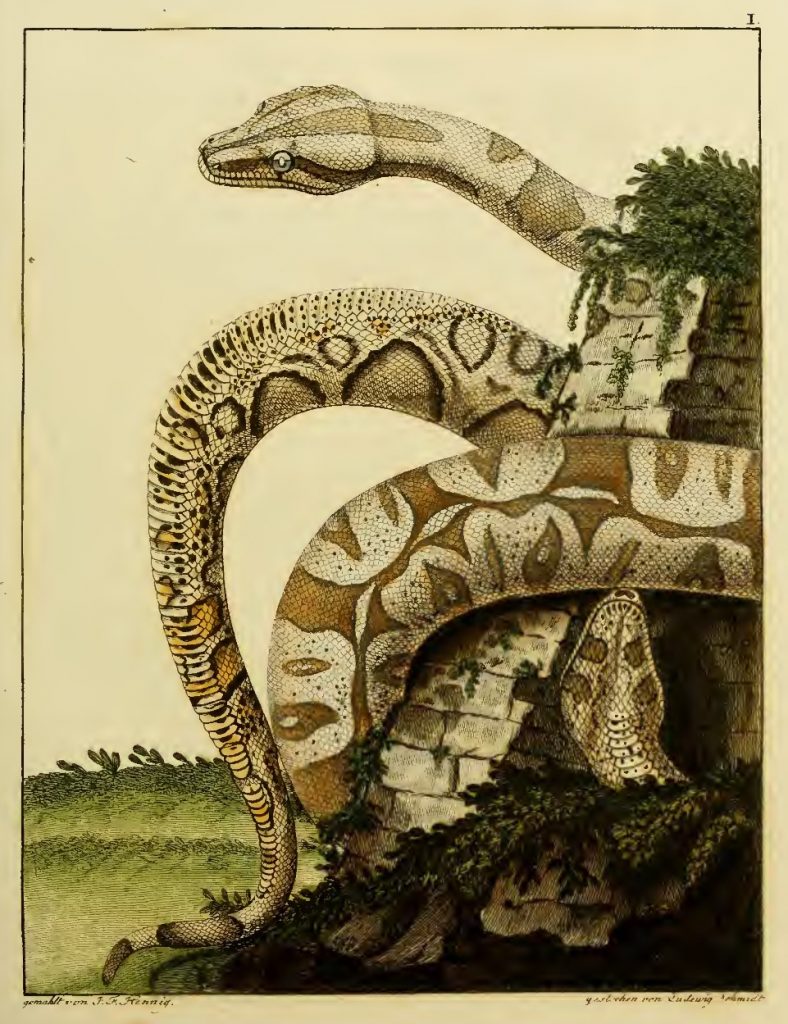

Boa constrictor, Merrem 1821 Longevity Boa constrictor can reach ages of more than 30 years as records from private and zoo collections indicate. The oldest Boa constrictor in captivity reached an age of more than 40 years

Reproduction The average litter size of Boa constrictor is about 20-30 young. Whereas large litters, containing 42 young have been observed in a captive breeding (T. Petzsch, pers. comm.). Mole and Urich report an observation from Trinidad made by “Mr. A. B. Carr of Caparo, a very careful observer, who has seen and caught many of these reptiles, says that the largest he has ever seen was a female 11 feet long. It contained 41 eggs “. According to them the mating season on Trinidad is in the months February and March (sometimes earlier). The authors made also the first observation of cloacal spurs being used in ritualized mating by the male to stimulate the female. They extended their observation from Boa constrictor to Epicrates cenchria, where they found the same function for the spurs. They refuted the false claim by others for the use of boid anal spurs in climbing

The largest litter we know of was reported by the Emperor Valley Zoo in Trinidad. A seven foot (2134 mm) Boa constrictor was captured as part of the zoo’s wildlife rescue program after she was discovered in a yard at a home in Diego Martin. When the snake’s pregnancy was observed, the Zoological Society of Trinidad and Tobago (ZSTT) decided to keep her at the zoo. The boa gave birth to a litter of 50 young and one stillborn

Another breeding of Boa c. constrictor was reported from the Emperor Valley Zoo in Port of Spain, Trinidad in 1969. This breeding produced a litter of 10 young

Boa Constrictor drawing by J. Wilkes, 1800. Behavior Boa constrictor is generally tractable when handled frequently and with care. This is one of the reasons why this species is popular among reptile keepers. Young and adult Boa constrictor are good climbers and will spend time above the ground on perches. Mole and Urich observed on Trinidad the highly arboreal habits of Boa constrictor , but mention also that they have never seen large boas climbing. The size of the boas they observed in trees averaged 6 or 7 feet (1829 mm or 2134 mm)

Diet The dietary list for Boa constrictors on the islands is sorely lacking. Because the boa is a generalist when it comes to prey items, it is assumed the diet consists of appropriately sized bats Boa constrictor on Trinidad capturing a Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus )

Mole and Urich state that on Trinidad Boa constrictor largely preys on Agoutis (Genus Dasyprocta ), based on fecal matter they investigated. In addition they also found young deer, Mazama americana carrikeri (the article stated Cariacus nemorivagas = synonym), and Ocelots Leopardus pardalis in stomach contents. They report that In the woods at Mayaro hunters frequently have had their dogs caught by the boas. Interestingly, they note that, while these boas in captivity readily prey on a variety of animals (mice, rats, guinea-pig, opossums, fowls and pigeons, snipes), they all seem to have an aversion to the domestic cat

Conservation Status and population in the wild CITES: Appendix II

Red List: Not listed

Catalogue of Life: (click here )

The National Center for Biotechnology Information: (click here )

CITES import/export data: (click here )

The islands Trinidad and Tobago are relatively large in size. Trinidad has a surface are of 4830 km2 and Tobago 300 km2 . Wildlife protection laws are enforced and in addition, Tobago has the oldest nature reserve in the New World. Boa fat and whole young Bothrops and Lachesis may be used in traditional medicine in Trinidad Boa constrictor on Trinidad and Tobago. The work of Auguste is intended to improve and renew datasets which are outdated, historical or incomplete Boa constrictor is not abundant nor distributed island wide as was previously reported

Tolson and Henderson list common threats for West Indian snakes

Predation by exotic mammals Alterations in the prey base Habitat destruction While Boa constrictor on Trinidad and Tobago might be subject to each of these threats, we consider it to be less threatened by introduced wildlife than smaller snake species. Alterations in prey base are relatively unlikely, since Boa constrictor is an opportunistic predator without a high degree of prey specialization. Commercial exploitation might occur illegally, however, given the pet industry’s obsession with “morphs” there is little to no interest in Trinidad boas since Boa constrictor is commonly bred and the market is saturated with captive bred specimens. In addition, Trinidad boas are not known to be of particular value to collectors, hence are not highly sought after. Habitat destruction and alteration are the major issues. Despite this lack of knowledge and the threats listed we are cautiously optimistic for the Boa constrictor populations on the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.

The CIA World Factbook lists the following environmental threats for Trinidad and Tobago: water pollution from agricultural chemicals, industrial wastes, and raw sewage; widespread pollution of waterways and coastal areas; illegal dumping; deforestation; soil erosion; fisheries and wildlife depletion

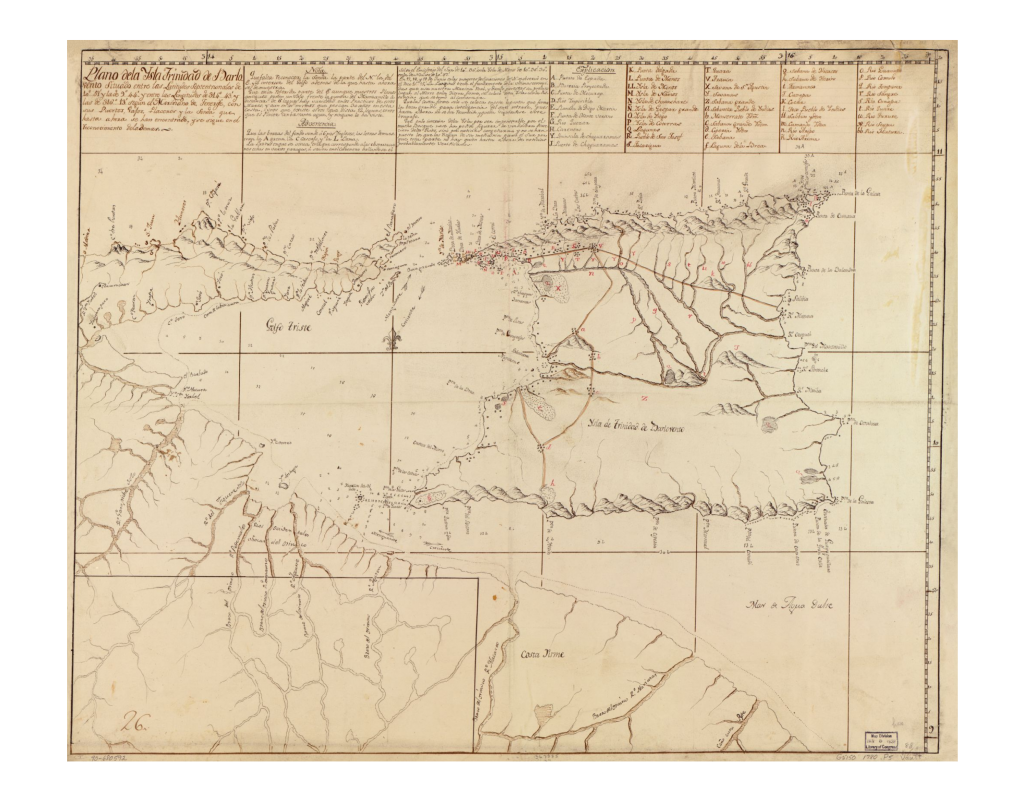

The maps illustrate the extent of habitat destruction and alteration due to development and agriculture.

Trinidad Tobago Early map of Trinidad, 1780. Early map of Tobago, 1776. Population ex-situ While common boas are kept in abundance in captivity, Boa constrictor constrictor with a confirmed origin of Trinidad or Tobago are rare guests in private, public or academic collections. A few glimpses about the importation history of Trinidad boas can be seen from former price lists like the ones here or analyzed comprehensively here

On display in these Zoos Common boas are on display in most zoos of the world.

Continue to Boa nebulosa

Citations

{2129430:R452E58D};{2129430:R452E58D};{2129430:42PMZG8L};{2129430:U4X2CEG2};{2129430:WK3KEMUL};{2129430:6C2G3SEZ};{2129430:4M2S3VRG};{2129430:B5KXQKJ6};{2129430:B5KXQKJ6};{2129430:KMLUG98W};{2129430:FKN8ZAUB};{2129430:I72FN4P2};{2129430:SFATR6IH};{2129430:CIEYLD8F};{2129430:ZABN4Y4X};{2129430:FTX7PLWT};{2129430:XIBSDFES};{2129430:AT6CPMFB};{2129430:FPPDZPML};{2129430:D3MAG6TN};{2129430:F9XC9DJD};{2129430:EE9GC9VZ};{2129430:QCZK7VE8};{2129430:AT8W4WR7};{2129430:PIYDEZ7L};{2129430:MWAJWBEI};{2129430:8JQN59AC};{2129430:6QFFGCRZ};{2129430:CWJEARHH};{2129430:6SCYJ9AY};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:LBFXPYAI};{2129430:TRWL9T99};{2129430:SWS6AK9A};{2129430:AMNVQLZB};{2129430:N5CTXHZL};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:YXETYAMN};{2129430:24XZEQ4B};{2129430:QLPHQ6ET};{2129430:QLPHQ6ET};{2129430:X4T97AYR};{2129430:24XZEQ4B};{2129430:CLZM3D4L},{2129430:YXETYAMN};{2129430:RBXII7B8};{2129430:I72FN4P2};{2129430:QCZK7VE8};{2129430:WQXDKUFP};{2129430:T4WFLTGY},{2129430:SZ5RJZQN};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:D662M6QL},{2129430:JGSWHCJF},{2129430:HBAWCUBU},{2129430:BFB8KQ43};{2129430:DDF8G6AQ};{2129430:Y2A4TJR8};{2129430:T5JQYMLG};{2129430:37RDY2N7};{2129430:YXETYAMN};{2129430:24XZEQ4B};{2129430:MYRI7AEY};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:24XZEQ4B};{2129430:E9KNHPRZ};{2129430:PHHY9L8K};{2129430:24XZEQ4B};{2129430:GIGKAEN7};{2129430:YXETYAMN};{2129430:FW9U5RTU};{2129430:24XZEQ4B};{2129430:YSSGA26J};{2129430:TE2NQLH9};{2129430:MYRI7AEY};{2129430:24XZEQ4B},{2129430:YXETYAMN};{2129430:VIMCTQSE};{2129430:CQY3KLAD};{2129430:LT9W8RJ3}

apa

author

asc

no