All but two of the vice presidents in the past 50 years have either run for president or become president when their predecessor died.

Dick Cheney, unlike almost all his recent vice-presidential predecessors, will not run for president. This allows him to sail above the normal rules of political behavior, not doing the things vice presidents do as they angle for the presidency. Cheney's accidental shooting of Harry Whittington last weekend is another example — an especially dramatic one — of his detachment from normal vice presidential protocol.

Two things defined vice presidents in the past: their powerlessness and their desire to become president.

Cheney reverses the historical pattern: he is powerful, immensely so, according to his adversaries, and he doesn’t plan to run for president.

In the past two weeks, I've gotten in my inbox four mass e-mail messages from vice presidential contenders, past, present, and future.

Each one was either a fund-raising appeal or a reminder to please not forget the sender’s political prospects:

- Former Vice President Al Gore sent one that said “George Bush is pursuing a truly breathtaking and unprecedented power grab."

- The 2000 vice presidential candidate, Sen. Joe Lieberman, decried “an abysmal failure” by Department of Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff during Hurricane Katrina.

- John Edwards, the 2004 vice presidential contender, told me that “President Bush and Vice President Cheney are in the pocket of the oil and gas industry.”

- And, potential 2008 presidential and vice presidential candidate Sen. Evan Bayh reminded me about his recent trip to Iowa, which holds its first-in-the-nation presidential caucuses in January 2008.

I also got one from 2004 Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry (subject line: “Evidence mounts against Cheney”), asking me to give money to his political action committee.

I have neither gotten, nor do I expect to get any e-mail solicitations from Dick Cheney — nor would I get one if I were a Republican Party activist in Iowa or New Hampshire.

Cheney remains an enigma

By Thursday the storm in Washington over Cheney’s hunting accident had faded away, leaving behind one familiar piece of political debris: six years after being elected vice president , Cheney remains an enigma, a fascination for reporters and for his adversaries.

Apart from occasional campaign fund-raising trips and a few tie-breaking Senate votes, his figurative place in American politics remains, as in 2001, that same undisclosed, secure location.

Naturally, Cheney will be a target for Democrats in the 2006 campaign, but it's not clear whether he'll be any larger a target than he would have been had he never accidentally shot Harry Whitttington.

On Wednesday the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) issued a statement drawing attention to the March 13 fund-raising appearance by Cheney on behalf of Republican congressional candidate John Gard in Wisconsin.

According to the DCCC, "Wisconsin families deserve to know why State Rep. Gard chooses to stand so close to Dick Cheney, one of the figureheads of corruption in Washington, D.C."

Asked about the political effect of Cheney's hunting accident, DCCC spokesman Bill Burton didn't directly answer, saying, "The more the American people know about Dick Cheney, the less they like what they hear. When Dick Cheney is at work at the White House, American families aren't exactly given a seat at the table." Cheney-as-corporate-crony remains, as in the 2000 and 2004 campaigns, the durable Democratic theme.

Over the past six years, Cheney’s foes have sometimes thought they finally had him: in the leaking of Valerie Plame’s CIA employment, for his work on the energy policy task force in 2001, for his links to his former firm, Halliburton, and for that firm’s Iraq contracts, for his role in overstating the risk of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

Each time the fish has eluded the hook. So, too, in the Whittington episode.

Resignation rumors

Nonetheless, rumors periodically sweep the Capitol that Cheney is about to resign. I’ve heard such rumors for at least 18 months. Former Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan was the latest to speculate about a Cheney resignation in her Wall Street Journal column Thursday morning.

Cheney, so different from previous vice presidents in almost every way, does call to mind one of his predecessors, Nelson Rockefeller. (Along with Rockefeller, whom President Gerald Ford jettisoned from his ticket in 1976, the only other veep of the past 50 years to not run for president or become president was Spiro Agnew, who was forced to quit in 1973.)

One of the indelible news photos of the 1970s was Rockefeller “giving the finger” to hecklers at a 1976 campaign rally in Binghamton, N.Y. Cheney sometimes seems to do likewise to his adversaries, especially those in the news media.

“I had a bit of the feeling that the press corps was upset because, to some extent, it was about them — they didn't like the idea that we called the Corpus Christi Caller-Times instead of The New York Times,” he told Brit Hume of Fox News in his interview Wednesday on how the Whittington accident became public.

Back in the days when the number-two man was little noticed, Woodrow Wilson’s vice president, Thomas Marshall, said the vice president is like “a man in a cataleptic state; he cannot speak; he cannot move; he suffers no pain; and yet he is perfectly conscious of everything that is going on about him.”

Contrary to Marshall’s dictum, Cheney speaks and moves and plays a central role in administration policy making, yet he acts mostly behind closed doors, making him the supreme oddity in this news media-saturated age.

One moment of accountability

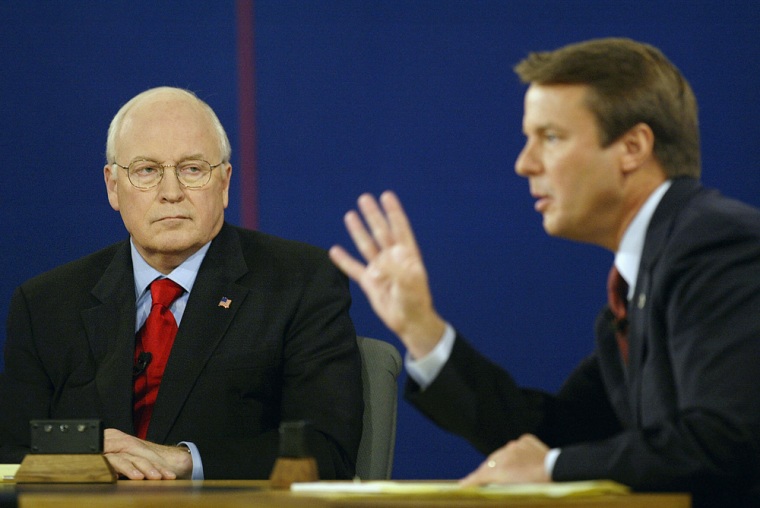

He has had only one moment of accountability: the 2004 election. His one notable performance in that campaign was his debate with vice presidential candidate Sen. John Edwards. The Democrat kept bringing up Cheney’s ties to Halliburton and American casualties in Iraq.

Cheney remained unrepentant: “What we did in Iraq was exactly the right thing to do. If I had it to recommend all over again, I would recommend exactly the right — same course of action. The world is far safer today because Saddam Hussein is in jail.”

Cheney also proved to be a sharp-toothed attack dog, turning to Edwards and berating him and Kerry for voting against $87 billion in funding for Iraq war operations, a vote Cheney attributed to fears of Howard Dean’s growing strength in the party in 2003.

Kerry and Edwards “decided they would cast an anti-war vote, and they voted against the troops. Now, if they couldn't stand up to the pressures that Howard Dean represented, how can we expect them to stand up to al Qaida?”