Now, we are all well aware that a growth mindset is optimal for learning, leadership and resilience. However, a recent study has highlighted a gap in our collective knowledge regarding naturalness bias. Aneeta Rattent, an associate professional at London Business School, states:

‘Most of the mindset research that’s out there looks at what/think and how that shapes the way that / react to different situations and performance as a result… What I love about Chia-Jung Tsay’s work is that it really flips this perspective and looks at how we are evaluating others.”

While we know that a growth mindset is undoubtedly superior in the results it produces, this research questions whether we, as a society, see it that way. Turns out, we don’t. For decades, business leaders have hailed the growth mindset and encouraged their people to strive towards thinking this way, all the whilst showing an unconscious preference for those with innate talents.

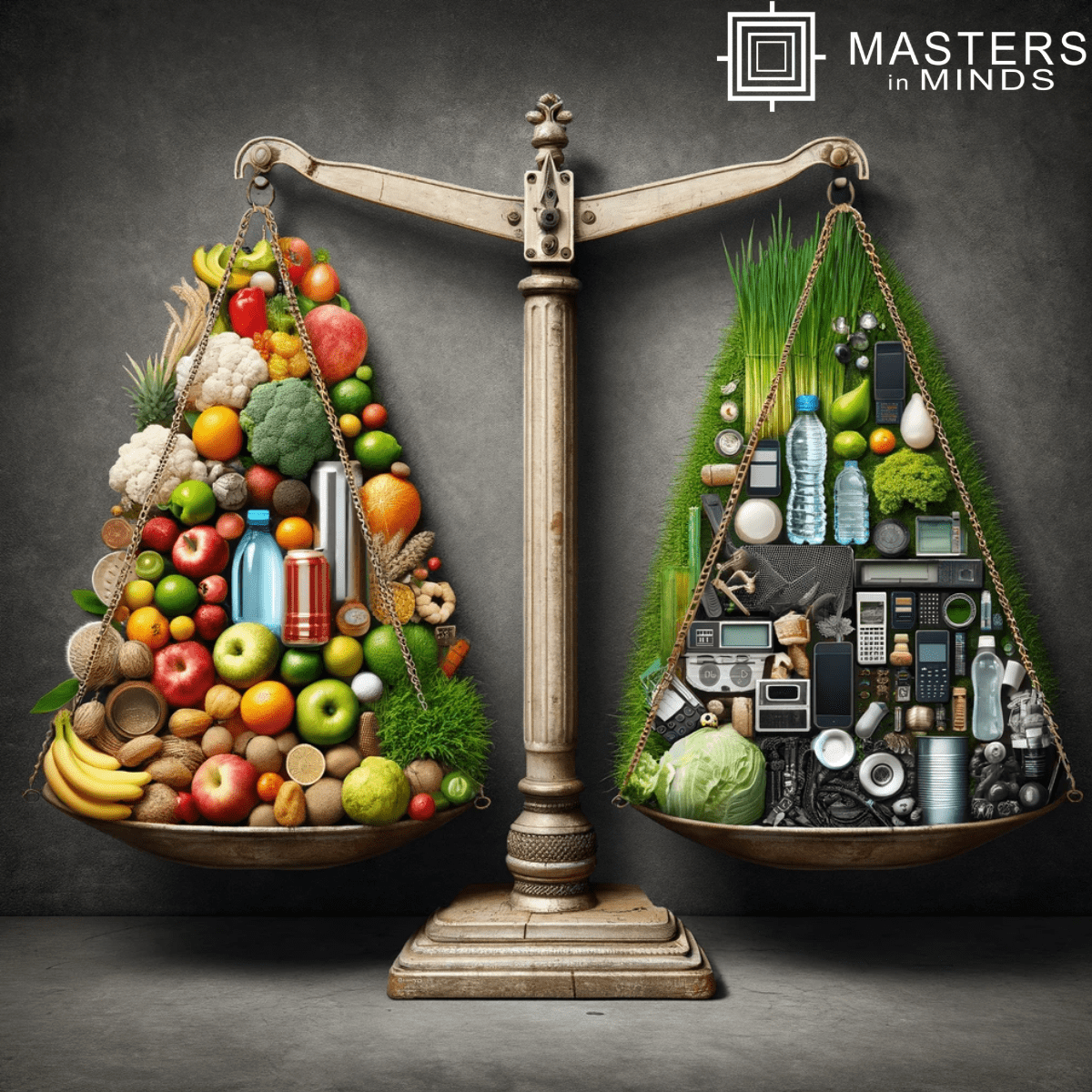

Naturalness bias refers to a more generalised bias, which is a cognitive bias that occurs when people assume that what is natural is inherently good or morally preferable. Most notably, this trend can be seen in skincare products, where often organisations will advertise their products as ‘all-natural’ or ‘chemical-free’ to imply their products are superior or healthier. This marketing exploits the assumption that natural ingredients are inherently better or safer. The latest study has discovered that we apply this same logic to people.

Development of Naturalness Bias

Most successful business leaders, athletes or artists attribute their success publicly to hard work and determination. Thomas Edison most famously claimed that:

‘Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.’

Regularly, you will hear stories about Steve Jobs’s disastrous Apple 111 computer failure or Michael Jordan being excluded from his high school team. These are used to demonstrate that hard work and perseverance are at the heart of our inspirational success. However, recent psychological research shows that overemphasising the importance of hard work can backfire in many professional situations thanks to naturalness bias. Essentially, these studies suggest that people have greater respect for those with an innate gift than for those who have had to work hard for their success. Ironically, this is the complete opposite of what our icons have led us to believe, who perhaps just wish to appear humble and grounded.

Naturalness bias was first established in consumer psychology, where Malcolm Gladwell was the first to apply the concept to human abilities in 2002, stating:

“On some fundamental level, we believe that the closer something is to its original state, the less altered or adulterated it is, the more desirable it is.”

He went on to propose that someone who had worked hard to achieve success has essentially gone against their ‘nature’ and their achievements, thus, would be less respected. Chia-Junh Tsay has since tested this theory, initially examining people’s perception of musical talent. The participants were all trained musicians who were presented with two 20-second clips from the same performance and the same pianist, although they were led to believe they were different artists. The musicians had to rate both clips, scoring the performer’s ability, chances of success and employability. Alongside each clip, participants were given a short biographical text; in one case, this text emphasised natural ability and, in the other, hard work. Tsay found that the biographical text had a great impact, with participants giving significantly higher ratings if they had read about the performer’s innate genius as opposed to hard work. Ironically, when participants were asked what was more important for musical achievements, almost all picked effort over talent, yet the majority valued talent more highly. TSay concluded that naturalness bias may be a result of the brain’s non-conscious processing.

Expanding the research, Tsay moved the experiment to an entrepreneurial context. This time, everyone was given a verbal business plan and a profile of a budding entrepreneur; half the group’s biographical information presented a striver/hard worker and the other innate talent. Again, Tsay found similar results with participants, on average, having greater respect for natural achievements and rating their business ideas more highly as a result. Interestingly and arguably most importantly, expertise did not reduce prejudice and, in some circumstances, heightened it. Such biased decision-making can come with a significant cost as when asked to compare various candidates directly, Tsay’s participants were willing to invest in entrepreneurs with poorer intelligence, fewer years’ experience and less capital – simply because they were said to have reached their current success through innate ability.

Building upon this further, Tsay then conducted yet another study working with colleagues at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, finding that children as young as five showed greater respect towards those with innate abilities. He concluded:

‘The naturalness bias is very generalizable across domains, ages, and cultures.”

Looking at an individual level, the naturalness bias might influence how we present ourselves to others, with a recent survey of 6,000 university alumni working as business leaders revealing that 80% of respondents focused on their effort and discipline over their innate ability. That figure was even greater when they had to imagine describing that journey to other people. The best solution, according to Tsay, is to give a more nuanced picture of our success without focusing exclusively on one element or the other, stating:

‘It’s possible that we have just been emphasizing all the hours of effort and education…But there are still some things that probably came easier to us, and it’s OK to reveal those balance out the narrative.’

However, it’s been argued that this bias is somewhat mitigated by contextual factors. While people may prefer natural geniuses for jobs requiring a single-star performer to shine, Christina Brown found that people prefer strivers for tasks requiring coordination. Sole emphasis on our innate ability may come across as uncooperative.

Other Effects of Naturalness Bias?

Firstly, naturalness bias influences hiring and promotion decisions. As discussed above, it’s possible that we value the work of those with innate abilities more highly than hard workers. However, this could be extended to adhering to societal norms, too. Studies have shown evidence of naturalness bias in hiring and promotion decisions with organisations. Research published in the Journal of Applied Psychology found that candidates perceived as having ‘naturally’ fitting characteristics (such as matching gender stereotypes for leadership roles) were more likely to be selected for higher positions, even when other qualifications were equal. This bias reinforces traditional norms and limits diversity in leadership positions.

Moreover, the naturalness bias is also prevalent in product development and marketing strategies. As discussed above, consumers often prefer products labelled as ‘natural’, assuming they are safer. Companies often exploit this preference, leading to the greenwashing phenomenon, where products may be marketed as natural or environmentally friendly without clear substantiation. This bias can influence consumer choices and impact market dynamics.

Thirdly, naturalness bias could and often does influence the perception of what constitutes the ideal workspace, with organisations typically favouring an abundance of natural light, greenery and open spaces. This is inherently believed to be more conducive to productivity and employee well-being. Whilst these elements can indeed have positive effects, it’s important to evaluate whether such design choices are universally beneficial critically. This element of naturalness bias could inadvertently neglect the needs of individuals who thrive in different workspaces. For example, those on the autism spectrum have unique sensory profiles and varying sensitivity to environmental stimuli. Some individuals with autism may prefer enclosed spaces or a more structured work environment. Alternatively, those with allergies, particularly hayfever, may not appreciate the additional greenery, or those with light sensitivity conditions such as retinal disorders or chronic migraines may not appreciate the abundance of natural light. This is not to say that organisations should change their office designs, but merely highlights that natural is not always better for everyone and taking this into account is crucial in fostering a diverse work environment.

Finally, naturalness bias can contribute to resistance to change within organisations. When changes are introduced that disrupt established practices or challenge traditional ways of doing things, employees may exhibit bias towards maintaining the status quo. This bias is rooted in the assumption that the current practices are ‘natural’ or the way things have always been done and, therefore should be preserved. This can hinder innovation, adaptability and organisational growth.

While our natural inclinations may lead us to favour what feels ‘natural’ or whatever’s closest to its natural state, it is crucial to be aware of this unconscious bias when making decisions. Recognising the presence of naturalness bias allows us to challenge assumptions, explore alternative perspectives and ultimately make more informed decisions. Or, at an individual level, we can adapt how we frame our experiences and success depending on the situation and our goal.

Click here to follow us on LinkedIn for more content.