The Last Days of Club Hubba Hubba

After a thorough renovation, about all that's left of Honolulu’s most infamous strip club is the legendary neon sign out front, and the memories of Hubba Hubba’s lurid past.

Hotel Street enjoyed much more through-traffic before it was restricted to city buses in the early ’80s. Club Hubba Hubba would advertise its dancers with saucy posters out front. Photo: William Lowe

“About the time I started at Club Hubba Hubba, it was on its way out and so was my career.” If there’s an ounce of sentimentality in Gilda, a former stripper at the legendary Hotel Street landmark, it doesn’t show. She talks about Club Hubba Hubba with the cold, forensic mien of a coroner conducting an autopsy. But in this case, the patient was still alive. Barely.

Photo: Courtesy of Gilda

It was 1993 when Gilda landed at the Hubba Hubba, 40 years after it first opened its doors as the premier venue of burlesque in the Pacific. What she found was a broken-down strip joint, grossly accented with the miasma of stale beer, cigarette smoke, roach spray, cheap perfume and Pine-Sol. Aside from the rats that populated a basement flooded from broken water pipes, Club Hubba Hubba was home to a cast of characters right out of a Tennessee Williams play. There was the head bartender, “Apache,” a blonde girl from Boston who fell in love with a local cop, which caused a scandal, since he was a married man with a family of five. There was Frank, who left his wife in New Zealand and moved into the club as a live-in handyman. He took cheesecake photos of all the dancers that he had to develop himself because Kodak wouldn’t process naked-lady photos. There was the womanizing back-up bartender and stockman Harold, who liked to dance to “Achy Breaky Heart” and rented out mini-refrigerators to dancers for five dollars a week. There was “LeeAnne, the mahu barmaid,” a guy who dressed as a woman but “liked the ladies.”

And then there were the girls. The dancers. The talent. Gilda describes them as a rag-tag group of former porn actresses, burned-out, big-name strippers from Las Vegas and the less desirable strippers in Honolulu who couldn’t get work at the hot clubs like Club Femme Nu or Club Rock-Za. They included the beautiful, yet obnoxious, Diamond.

Photo: Courtesy of Gilda

“Diamond was one of the passable-looking ones,” Gilda says. “Long, curly, flowing, brunette hair but already with a drug and alcohol problem. She was 27 years old. I told her, Sweetheart, in 10 years you’re going to be a bigger mess than I am. She’d walk slowly down the runway in a bikini with a glassed look. She didn’t dance. Just walked slowly to the music of ‘Enigma.’ She thought she had the world by the balls but she was being used by men.”

Others making up the catwalk menagerie included Liberty West, “a talented older dancer just a little bit past it, a headliner from Vegas who danced to Broadway show tunes;” Nevada Sands, once upon a time beautiful and slender, but, having gained a lot of weight, she now stripped down to Spandex garments covering her body; and Kandy Barbour, a gorgeous former porn star insecure about her looks, who, à la Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, would ask “‘Do I still look good?’” Gilda says, “I told her what any good husband would … You look wonderful, dear.”

Overseeing everything was long-time owner Tad Matsuoka, who, when the club fell on hard times, housed the dozen or so girls in grimy upstairs rooms where they shared one shower (“with no water pressure and slimy with fungus”) and a small kitchen (“with an old stove, a washing machine and tar-paper flooring”). Gilda and the other upstairs residents referred to the place as the “Hubba Hovel.”

In 1994, the Hawaii-based TV show Byrds of Paradise shot part of an episode in Club Hubba Hubba. At one point, lead actor Timothy Busfield looked around at the shabby club and its inhabitants and said, “How could anyone work here?” Gilda couldn’t remember if it was a line from the script or just a general observation by the actor.

Shortly after that, Gilda left Club Hubba Hubba and her life as a stripper. As she walked away, the famous green neon sign boasting “Live Nude Shows” hanging on the side of the building blinked bravely on.

Today, the sign still clings to the side of the two-story, red-brick building. But the naked neon tube girl hasn’t kicked up her leg since 1997, when the club finally closed. As writer Brian Nicol noted in a 1980 HONOLULU Magazine piece on Chinatown nightlife, newspapers and magazines had been writing Hotel Street’s obituary for 30 years. But when he walked into Club Hubba Hubba that year, he found the place fairly thriving, although the club and its dancers were already showing signs of age. By then, Matsuoka had stopped his earlier practice of bringing top burlesque dancers from Las Vegas and entertainers from Japan and housing them in nice apartments. The era of the “Hubba Hovel” was in full bloom.

In 1969, Honolulu Associated Press reporter Bruce Dunford wrote a piece headlined, “Honolulu’s Once Lively Hotel Street Nears Death Gasp.” City planners, it seemed, wanted to bulldoze Hotel Street as part of a mass-transit project. In that report, Dunford quoted the ever-morose Matsuoka on the future of Club Hubba Hubba as saying, “Sure, it’s dying. It may not even last another year. I’m losing money, even though I have a floor show and draw a local crowd.” What is interesting about Dunford’s article is that it was picked up by several Mainland newspapers, including papers in Florida, Connecticut and Indiana. Why were so many people on the Mainland interested in a grimy little street in Honolulu? Today, Dunford says the story was probably printed so widely because of the millions of servicemen who had partied in downtown Honolulu ever since World War II. Servicemen told their friends about Hotel Street when they got home and word spread through the military that, if you are in Hawaii, Hotel Street is where the action is, he said.

But Club Hubba Hubba, in 1969, was nowhere near death. The mass-transit system was never built, although Hotel Street eventually closed to regular traffic and was converted into bus lanes. That lead to a decrease in business. But the thing that killed off Club Hubba Hubba, ironically, turned out to be a reevaluation of what is considered obscene and what isn’t. The U.S. Supreme Court, in 1973, said, basically, one man’s obscenity is another man’s hot night on the town watching ladies take off their clothes on stage. It was up to local jurisdictions to set community standards. In “hang loose” Hawaii, this meant an increase in clubs featuring not only naked dancers but, in some cases, even actual sex on stage. Club Hubba Hubba and the Forbidden City on Kalakaua Avenue were no longer the only skin games in town.

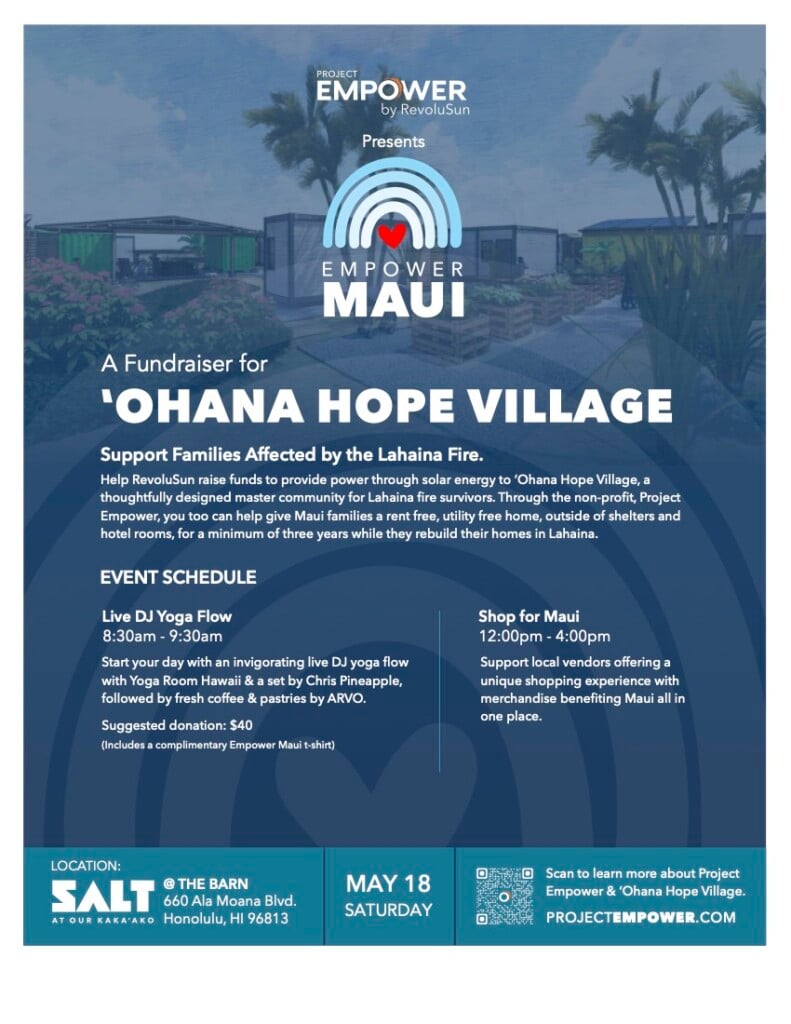

Another funny thing happened as Matsuoka and others lamented the imminent demise of Hotel Street businesses: A movement arose to save historic Chinatown and downtown buildings and breathe new life into the area. The Honolulu Culture & Arts District Association was established in 2001 to develop the area as a center for the arts, entertainment and dining out and to help landowners rehabilitate their properties.

When you walk into the buildings that housed Club Hubba Hubba today, you smell not unpleasantness, but the sharp, agreeable smell of fresh paint. Gone are the horseshoe-shaped bar, catwalk and pool table. At least one of the stripper poles has been stuck into storage for posterity. The empty rooms look huge, with 25-foot-high ceilings.

Lee Stack, a member of the Stack family, which owns the buildings at 25 North Hotel St., said the family has turned the property into space for up to four offices or possibly two upstairs offices and a street-level restaurant. The upstairs lanai, which had been a chicken coop and a place where strippers sunbathed nude, to the delight—or alarm—of neighbors, has been transformed into modern restrooms. Downstairs, much of the original brick and plaster work has been saved, and floor-to-ceiling windows look out over what will become a courtyard in the back. The Stacks received a state “façade grant” that helped renovate the front of the buildings.

With the renovation underway, one of the main questions was whether the developers would be able to keep the famous 11-foot-tall, six-foot-wide Club Hubba Hubba neon sign. For one thing, it’s against building code to have a sign on a building advertising something that doesn’t happen inside the building. But, with the help of supporters, including the perennial signage foe Outdoor Circle, Mason Architects, which is overseeing the renovation, was able to get a variance to keep the sign up. The sign was designed by famous Honolulu neon “bender” Robert “Bozo” Shigemura, who also made the Hawaii Theatre marquee and the neon sign for the Wo Fat Chop Sui restaurant in Chinatown. Right now, the plan is for the Hubba Hubba sign to be restored by Von Monroe, owner of Strictly Neon.

“I’ve been looking forward to restoring the Club Hubba Hubba sign for years,” Monroe said. “Being a neon bender, I’m excited about it.”

Steven Fredrick is a history and vintage film buff who turned his passion into business. Along with screening old movies, he conducts walking tours of Honolulu as part of his “Honolulu Ghost and Mystery Tours” business. Those include “The Charlie Chan Mystery Tour,” “Hawaii Wartime History Tour” and “Honolulu Ghost Tour.” He doesn’t include Club Hubba Hubba in his ghost tour, but he does point out to visitors, in the interest of history, that the club wasn’t around in World War II as many people think. The buildings at 25 N. Hotel St. were used as restaurants and cafés, becoming Café Hubba Hubba in 1947. It was changed to Club Hubba Hubba in 1953, well after World War II.

One could disagree with Fredrick’s choice not to include Club Hubba Hubba on his ghost tour. Ghosts are just memories that won’t go away, and there are plenty of those haunting the Club Hubba Hubba property. The two buildings were built in 1899, and survived the 1900 Chinatown fire that burned down almost everything else. There must be some ghosts from that period hanging around. The buildings were used by dentists and photographers and cooks and barbers. All of them had stories to tell. Club Hubba Hubba has starred in many TV shows and movies. It was in a number of Magnum P.I. episodes, including episode 133, “Death and Taxes,” the first episode to be produced by Tom Selleck. It was a regular backdrop for Hawaii Five-0, including episode No. 5 (“And They Painted Daisies on His Coffin”) in which, after being grilled by McGarrett, a stripper coyly asks the crime fighter, “Why don’t you catch my act sometime?” Steve just smiles at her the way he did when chicks dug him.

Hotel Street can be rough, and there were more than a few fights in Club Hubba Hubba over the years. Not all ended in tragedy. In the 1970s, there was a big fight in progress at the club when HPD officer John Shaw got the call. He raced in his three-wheeled police “popsicle wagon” to the scene. It had been raining.

“I was going a little too fast,” he recalled recently. “I hit the brakes and went into a skid. God knows how I got onto the sidewalk and into the bar without hitting anybody or anything. I ended up IN THE BAR. On my bike. I took off my helmet and threw it to the ground because I was pissed. Then I noticed the fight had stopped and everyone was laughing.”

The ghosts must still laugh about the crazy cop who broke up a fight by accidentally crashing into the bar.

Gilda, who asked that we only use her stage name because she still lives in Honolulu, has become something of the keeper of ghostly memories, at least from the short time she was there. Along with performing on the catwalk, she also served as a “mixer,” one of the ladies who sits down with gents and encourages them to buy overpriced champagne. Most of the girls did both, because there was more money to be made as a mixer. One of the best mixers was the unfortunate Nancy.

“She was a brilliant mixer,” Gilda said. “College educated. She made a lot of money, for herself and the owner. But she lived beyond her means. One customer convinced her to invest in soybean stocks and she lost $5,000.”

Another customer, a well-known, prosperous local businessman with a family, had a weakness for champagne and Nancy, Gilda said.

One night, Gilda and Frank the Handyman finished work at 3 a.m. and, as had become their habit, went upstairs for a drink and some popcorn.

“We cooked a big bowl of popcorn, and this guy somehow got into the building because he wanted to be with Nancy,” she said. “He was coming up the stairs, drunk. Frank got out a machete and waved it at him. He wouldn’t stop. Frank hit him with the machete and there was blood everywhere. The man knew his goose was cooked. He didn’t want to get caught by the police, so he left, leaving a trail of blood. It was like a Tarantino movie. Frank got out the mop and cleaned up all the blood drops. Then we finished the popcorn. Just another day at the Hubba Hubba. Do your job, eat some popcorn, clean up the blood, finish the popcorn.”

The intruder was never arrested for breaking into the club, but Nancy, “the diabolically brilliant mixer,” became addicted to champagne, eventually spiraled into dementia and became a ward of the state.

Gilda remembers another mysterious thing about Club Hubba Hubba. The club had two small dressing rooms downstairs for dancers, one of them set aside for the divas, or featured acts who preferred solitude. Gilda recalls that, on the cigarette smoke-stained door of the diva dressing room, someone long ago had written: “Laissez les bons temps roulez!” It’s a famous French phrase from New Orleans—“Let the good times roll!”

No one knows who wrote that ghostly message. But you have to believe that, in the nearly 50 years Club Hubba Hubba was in business, there were many times they must have.

Timeline

- 1886: Two new buildings are constructed on Hotel Street, one brick, the other wood.1899: Lincoln Loy McCandless purchases lot 25 (future site of Club Hubba Hubba) and lot 21 and builds a new, two-story brick building incorporating the existing brick building.

- 1934-35: Clyde C. Hopkins runs a restaurant on the ground-floor level of lots 21 and 25.

- 1936: Green Front Café occupies the ground floor level of lot 21 and 25.

- 1940: The name changes to Aloha Café, and is popular with Navy and Army personnel, with regular patrol visits by military police. The café becomes known for live nude shows and swing music.

- 1947: Café Hubba Hubba opens at 25 N. Hotel Street.

- 1953: Name changes to “Club Hubba Hubba” and the club becomes a prominent location for jazz music, burlesque shows and, later, strip shows.

- 1980s: Chinatown’s seedy reputation begins to hurt business at Club Hubba Hubba, with tales of drugs, gambling and pool halls. Similar adult clubs closer to Waikiki with more parking draw off Hubba Hubba customers.

- 1997: Club Hubba Hubba closes after 50 years and the building is boarded up and the sign turned off.

- 2010: Construction begins for the restoration and rehabilitation of the Club Hubba Hubba Building by the Stack family (Marks-McCandless heirs), with drawings by Mason Architects. The rehabilitation plans include a ground-floor restaurant and office space upstairs.