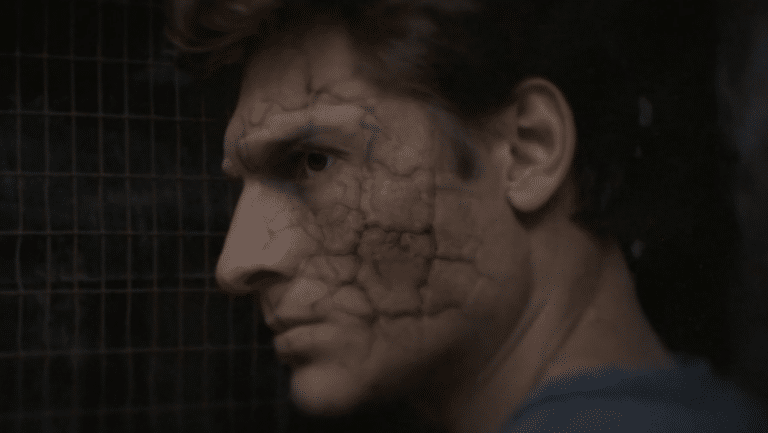

Nosferatu, as played by Max Schreck in the 1922 film of the same title, was a lot of things, and what he was depended, in part, on the viewer. He was a vampire, of course — albeit a strange, rodent-like vision of the folkloric bloodsucker. He’s one of cinema’s first monsters, and in time he would become an iconic figure of the genre.

He was something worse to Florence Balcombe, the widow of author Bram Stoker. Although she never saw the film, she knew it for what it was: A German expressionist knockoff of Dracula, made without permission or payment. Balcombe sued the filmmakers for copyright infringement, bankrupting the studio. Balcombe wanted more — she wanted all negative and all prints of the film destroyed. That the film exists at all today means Nosferatu was, on top of other things, essentially contraband.

But that’s not all Nosferatu was. To a certain sort of viewer, Nosferatu was something even more menacing than a vampire or a theft of intellectual property. He was a Jew.

This is a story set in the past, but just barely in the past, and in a past so terrible that contemporary Jews often still recoil when a vampire is compared to a Jew or vice versa.

An example, and the example that caused this article: A short while ago, Phil Nobile Jr., editor-in-chief of FANGORIA, posted to Twitter a photo of Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner taken for the cover of Time Magazine.

Noting the man’s awkward, stiff position, Nobile paired it with a famous still of Nosferatu. This produced two responses, or, more properly, three: Non-Jewish respondents were either delighted by the parallel or argued that Kushner more closely resembled a haunted doll, which is fair.

In the meanwhile, Jewish respondents were mortified.

Kushner is Jewish, and, regardless of how personally awful he is, pairing him with an image of a vampire — and particularly with the image of Nosferatu — recalls a historic, if now little-remembered, anti-Semitic use of the vampire.

Nobile quickly took down the image with an apology. Like many non-Jews, he did not know of this history, and he reached out to me to share it.

I had noted elsewhere on Twitter that it’s a good idea, when comparing a Jew to a mythical creature, to do a quick Google search and see if that image has been gleefully used by anti-Semites, as anti-Semites seem to love to draw this sort of parallel.

Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling ran afoul of this several years ago, including in her books hunched, greedy, hook-nosed goblins who worked exclusively as bankers. To many readers, this was uncomfortably close to a supernatural rendition of the “happy merchant” image of Jews as hand-clutching, grotesque, and greedy. Worse still, the film adaptation used a location that prominently featured a Jewish star, which must be a low-point in cinematic tone-deafness.

I’ll note that Jews don’t bristle at merely any supernatural representation. The 1941 Universal movie The Wolf Man was authored by Curt Siodmak, a Jewish screenwriter who had evacuated Europe to escape rising fascism, and he was quite open in interviews that the film represented the Jewish experience. Rewatching the film knowing this, The Wolf Man gains new depth, especially in its representation of Europeans turned into ravaging mobs and victims marked by the appearance of a star. (There has been a small movement to reclaim the werewolf as an unusual but poignant representation of Jewishness, particularly furthered by the original American Werewolf in London, with its Jewish lead characters, and more recently with the 30 Rock/Tracy Morgan novelty song “Werewolf Bar Mitzvah.”)

Jews have even made efforts to reclaim the vampire, perhaps starting with the 1967 Roman Polanski satire The Fearless Vampire Killers (which included a Jewish vampire grinning at a crucifix and saying “oy, have you have the wrong vampire!”) and the Israeli vampire series Juda, which include strict rules for drinking blood that call to mind Jewish kosher laws.

But not Nosferatu. At the moment nobody is reclaiming him, even though the film’s screenwriter, Henrik Galeen, was Jewish. In part, it’s because the makeup for Count Orlok, the film’s vampire, inevitably recalls anti-Semitic caricatures, which have long presented Jews as rodentlike, with hooked noses and clutching hands. Moreover, it’s because the mythology of the vampire is closely linked to the Blood Libel, an ancient and historically deadly anti-Jewish slander that accused Jews of requiring human blood at Passover.

But, perhaps most painfully, it’s because of the film’s connection to actual Nazism, which was not intended by the filmmakers. But the Nazis were voracious in scooping up imagery that they could adapt to their needs.

At the film’s premiere in 1922, a former elementary school teacher who had become enamored with nationalist politics was in the theater, and was thrilled by the film. This was Julius Streicher, who would become the founder and publisher of one of the essential pieces of Nazi propaganda, the antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer. One issue of the paper was dedicated specifically to parallels between Jews and vampires.

These sorts of analogies show up throughout Nazi propaganda, sometimes explicit, sometimes implicit. Alfred Rosenberg, who, despite his Jewish-sounding name, was head of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories and premiere Nazi theorist, particularly loved to analogize Jews to vampires. Hitler himself employed the comparison in Mein Kampf, writing “The end is not only the end of the freedom of the peoples oppressed by the Jew, but also the end of this parasite upon the nations. After the death of his victim, the vampire sooner or later dies too.”

Anti-Semitism is remarkably protean. Anti-Semitic ideas rarely go away, but instead constantly adapt. So while Jews are rarely represented as vampires nowadays, modern anti-Semitism still borrows from vampirism, presenting Jews as a cursed infestation, able to shift form, ravenous and destructive. Just now there is something called the Great Replacement theory, which is finding increasing popularity in far right circles in the United States. At its core, it’s just an updating of the vampire myth. In this version, Jews are masquerading as white in order to push for an invasion of dark-skinned foreigners.

There it is: The Jew as shapeshifting monster, seeking to infest and devour its host. When tiki torch-carrying protesters at the Unite The Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia chanted “Jews will not replace us,” this is what they referred to.

Jews, for the most part, understand the temptation to compare certain Jews to supernatural monsters. Trump’s political advisor Stephen Miller, with his pale skin, widow’s peak, and sinister eyes, already looks like some folkloric monster, and the fact that he was one of the architects of White Nationalism at Trump’s White House makes it very tempting to represent him as some sort of ghoul or vampire.

We get it. It still makes us nervous, and it’s a nervousness that comes in the shadow of genocide.

Bunny Sparber is an award-winning author and journalist from Minneapolis, MN. He is the creator of Absolute Bleeding Edge, a weekly email magazine looking at avant-garde and experimental film, music, art, literature, and performance; subscribe to it at https://abe.mailchimpsites.com/