-

Featured News

Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg

By Harvey Kubernik

Catching Fire – The Story of Anita Pallenberg, debuts in New York as a sneak preview at 7:30 pm at IFC Center on Thursday, May 3, 2024 and may open at more theaters at a later

By Harvey Kubernik

Catching Fire – The Story of Anita Pallenberg, debuts in New York as a sneak preview at 7:30 pm at IFC Center on Thursday, May 3, 2024 and may open at more theaters at a later -

Featured Articles

The Beatles: Their Hollywood and Los Angeles Connection

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or

By Harvey Kubernik

JUST RELEASED are two new installments of the Beatles’ recorded history, revised editions of two compilation albums often seen as the definitive introduction to their work.

Or -

Confinement and Escape: The Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street at age 50; Interview with Engineer Andy Johns

by Harvey Kubernik

“I think people make the mistake of putting too much information on a CD because you can afford to, time-wise. But Exile was a slow, slow thing. It wasn’t as immediate as albums characteristically were in those days, ’cause there were two albums. I think another thing with Exile—now that I think about it. Yeah… It was a very ‘Keith-spirited-by-Keith’ album.” – Chrissie Hynde to Harvey Kubernik 2004 interview.

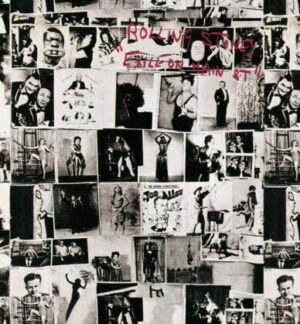

I remember in June 1972 receiving an advance test pressing long LP player of the Jimmy Miller-produced Exile on Main Street from an Atlantic Records publicist at their Sunset Boulevard office. The Los Angeles-centric Exile on Main Street album package artwork and design were created by John Van Hamersveld who collaborated with photographer Norman Seef on the product graphics.

Earlier in ’72, the Rolling Stones, record producer Jimmy Miller and engineer Andy Johns relocated to Hollywood after cutting the basic tracks for Exile on Main Street in the 16-room Villa Nelcotte in the South of France. Overdubbing and mixing sessions were subsequently done in Hollywood at the landmark Sunset Sound studios and mastered at Artisian Sound Recorders on the same street.

Sunset Sound was built by Alan Emig, who had come from Columbia Records. He was a well-known mixer there and designed a custom built console for Sunset Sound. Salvador “Tutti” Camarata, a trumpet player originally and an arranger, and did big band stuff in the 1940s and ‘50s had a friendship with Disney Studios and decided to build a recording studio to produce the Disney/Buena Vista records by Hayley Mills and Annette Funicello.

“The Sunset Sound room was very unique,” volunteered Bruce Botnick engineer and co-producer of the Doors during 1966-1971 in a 2009 interview we conducted. “Tuti Camarata did something that nobody had done in this country. He built an isolation booth for the vocals. And later on I convinced him to take the mono disc mastering system and move it into the back behind what became Studio 2. And we turned that into a very large isolation booth which we used to put stings in. With the stings being in the large isolation booth the drums didn’t suffer so we were able to make tighter and punchier rhythm tracks than any of the other studios in town were able to do. ‘Cause everybody did everything live in those days. You did your vocals live. You did your strings and your brass live. And the rhythm section. And this was a big deal.

And then add to it the amazing echo chamber that Alan Emig designed. There was a good selection of microphones at Sunset Sound. It was all tubes, except for some Ribbon, RCA’s and a few Dynamics, they were all tube microphones. U-47’s, Sony.”

Engineer Gene Shiveley was based at Sunset Sound in 1968 and involved in the recording, overdubbing, and mixed Beggars Banquet. He worked with producer Jimmy Miller and Mick Jagger on tapes recorded earlier in England at Olympic studios with chief engineers Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer, assisted by tape operator, Phill Brown.

“Why Sunset Sound was so important at the time was because of the Musicians Union. If you were on the Columbia Records label you had to use their studio and have union breaks,” explained Shiveley to me in 2018. “If you were on RCA Records, you recorded at RCA. You could not do independent recording. And the union enforced everything. Tuti had Buena Vista Records and he produced Annette Funicello and the Mouseketeers from the Mickey Mouse Club. [Western and Wally Heider were two other regional non-union houses].

“The magic of Sunset Sound was that they had the best equipment. I got there and it went to four-track recording from three-track. It was all tubes. Everybody wanted to try things out at Sunset. All the manufacturers. Because Tuti created this rebellious studio against the union. Tuti would go to England all the time and bring back tester equipment from there.

“Tuti had created this thing called Tork phase. Four speakers and had developed what we now know as the pan pot thing with this guy who discovered that there is a particular dip to get your positioning between what is left and right stereo to get that centered. That particular phasing thing is. He also worked on dealing with tubes and how hot they were in the amplifiers which were under the floor. And the control room just had to be freezing.

“Without Tuti Camaratta studio technology would never be where it is now. Sunset Sound had the best collection of microphones and no one else had that stuff. Other than the big labels. RCA, Columbia and Capitol had them. Sunset Sound had custom speakers that Tuti had built. JBL components and the guy who built them still does the work at Sunset. It was as state of the art as you could get. Tuti was also a well-respected musician. All the big bands guy. Tuti was so fed up with the union. Rock and roll people started using his room. Their echo chamber was just one of the most wonderful things in the world. Bill Robinson built the original one in Capitol Records. Tuti hired Bill to come over and duplicate that. He did and he did it better at Sunset.

“Jimmy Miller and the Stones had done some rough mixes in England at Olympic when the Brian Jones thing was coming down. He had gotten busted and could not come into the United States. Jimmy wanted to mix it here to get a fresh sound. Because Beggars Banquet would be a turn for the Stones. It was really a rhythm & blues album.

“I met and knew Sir Edward Lewis of Decca Records in London who came to Sunset Sound all the time. He would come to the US and knew very well Tuti Camaratta. The Stones were on Decca label in the UK and London in the US. Mick came into Sunset Sound and Tuti introduced me to Mick. And Mick, Tuti and I decided we should immediately work together. It’s spring of 1968. Mick then heard an album I produced by Touch done at Sunset Sound and wanted me to work together with him. In the very beginning Mick didn’t really know about my training and work at King Records with Syd Nathan and James Brown in Cincinnati. Then he found out later and we talked about it.

Beggars Banquet album with Gene Shiveley’s first name only credit on the back cover.

“Many tapes and tracking sessions from Olympic studio in London of the Beggars Banquet sessions had just arrived to Sunset Sound. Jimmy Miller had sent the tapes over. Keith could not get into the country because of a drug thing. They sent everything to Sunset. Jimmy and I probably spent two weeks going over the batch of tapes that were on all kinds of formats. Some of the things weren’t finished so we started to organize all the various pieces. There were some things recorded on cassette! Tape speed differences. Before we really got going we put everything on four-track.

“Then, Sunset Sound got an 8-track machine. ‘Mick and Jimmy. Would you like to use this 8-track machine out?’ Mick was like ‘wow!’ His eye lit up.

“To be really honest as far as working and knowing him during Beggars Banquet, I would drive and go pick Mick up and take him to the studio. He didn’t have a car. I had a blue Volkswagen bug. They had just come out. We would stay at the studio until we dropped. And then go back. There wasn’t a lot of partying going on,” stressed Gene.

“Jimmy Miller. A gentleman. He knew about music. He knew about percussion. And he was a great drummer. I never looked at him as a father figure and he wasn’t a corporate guy. He had produced Traffic. I wasn’t a big Rolling Stones fan. I had worked at King Records with James Brown and in the real funk. And, not being a huge fan or collector of the Rolling Stones actually worked to my advantage. ’Cause I was not impressed. And Jimmy liked that. Because he liked that I came from the funk. James Brown is total feel. He works from total feel. Where Mick works from deliverance. Of understanding the song and the lyrics. And getting the song and the story across. And knowing how to deliver the verse, the bridge and the chorus. How to take each one of those and pull the best out of those. Whereas James Brown is simply just blow it out there and make you feel good. They are very different. Mick approaches a vocal with over annunciation with everything so you never miss a lyric. You know what those lyrics are.

“I don’t remember if we used a foam covering or a wind screen when we did vocals but he engulfed the microphone. We tried different microphones. I would use a combination of a RE -20 and ribbon RCA 77. Because that’s what I used on James Brown. Mostly a ribbon microphone so I could get the heavy hunches. I did not use the traditional Telefunkens and things like that.

“Jimmy Miller and I grew a lot off from each other in this process. As a producer, you know, he sort of worked with me in what he was thinking in terms of sounds and where he was thinking of going. This was nothing like the old Stones. Jimmy is thinking rhythm & blues. Charlie Watts on tape blew my mind. Absolutely. He came from jazz.

“Jimmy was the right producer for the Rolling Stones because he understood the ear for making a hit record. He understood feel. He understood what it takes to get the kick drum at the right place. He understood all of those things and how to build a record.

“I remember with Jimmy the first rough mix I threw up. He was floored. Because of the way I mixed was brilliant. Because bass and kick predominant and then the back beat filling everything around it. To that point it was more like acid music. Thinking ‘Let’s put the vocal up and mix everything around that.’ I’m coming from funk. I’m looking at it from a very different way.

“So, Jimmy is hearing this whole thing develop and that was what he was looking for. That is why he pretty much wanted to get out of England. To get the kind of bottom that you can get here. The minute Jimmy and I actually started working Mick was there. We had a lot of things to do before we even started mixing. ‘Salt of the Earth’ wasn’t even written yet. I remember that session vividly. The basic track was already cut. The piano part by Nicky Hopkins was on it but different. Nicky came in and did the new part at Sunset Sound. They had a gorgeous Steinway,” marveled Shiveley.

“Nicky’s magic was talent and feel. My first impression with Nicky and hearing him play he could have sat in with the Fabulous Flames in Cincinnati at King Records and just done great. He would have blown Syd Nathan away. Nicky and I became buddies for years. Phenomenal piano player. ‘Salt of the Earth’ got completely re-structured at Sunset Sound. Keith sings the intro and we also kept his guitars as well as the drums and the bass.

“Singers Shirley Matthews, Clydie King, Oma Drake and Ginger Blake of the Honeys in ’68 are heard on ‘Salt of the Earth.’ I got the background vocalists together. I also worked at a place with some real good black musicians. There was a guy, Jerry Peters, the musical director at the Watts Street Church. His dad was the pastor. He started pulling in pieces from there from the choir. At the time of this session, they had started to build the second chamber at Sunset Sound. So, we did one set of vocals in that echo chamber. They were inside the echo chamber. Right? And then we took them into the other echo chamber and overdubbed them again. And that’s how we got that cool and really awesome sound.”

Shirley Goodman of Shirley & Lee fame had a big hit single in 1956 with “Let the Good Times Roll” and was an active background singer around Hollywood in the late sixties and seventies and heard on Jackie DeShannon and Sonny & Cher recordings.

“Around 1965, ’66 I met Shirley Matthews,” vocal contractor Ginger Blake reminisced to me in 2018. “She was a social worker and also did sessions, too. We started becoming friends and she wanted to know if I wanted to do some background singing. ‘Sure.’

“I came to the ‘Salt of the Earth’ session in my blue ’64 Thunderbird and I remember getting so excited, and parking in the lot, leaned over, because it didn’t have electric windows, and leaned over to roll up the window, fell over the console, and I cracked a rib. I had to sing with a cracked rib! I walked into Sunset Sound. I had been in that room many times with Gary Usher. We did the Annette Funicello stuff there. So many artists there. I saw the carpet on the floor, like a Persian rug and it looked as though there had been a little party going on there. Still some remnants of food on the floor. There were five of us. We did the Stones’ session. Mick Jagger and Jimmy Miller weren’t at the session. Just Gene the engineer. Absolutely the most fun. So exciting to hear Mick’s isolated vocal over the big speakers. And then our voices. We’ve been listed as the Watts Street Gospel Choir on the internet but not on the album.”

“One of the great things about recording in Hollywood earlier at RCA [1964-1967] was after a session you’d walk into the car port and literally on the other side of the building was [jazz club] Shelly’s Manne-Hole,” enthused Charlie Watts in my 2014 book Turn Up The Radio! Pop, Rock, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972.

“While we were recording in Hollywood, I went to Shelly’s Manne-Hole twice—once to see Charles Lloyd, Albert Stinson [with Gabor Szabo and Pete LaRoca], and the Bill Evans Trio with Paul Motian on drums [and Chuck Israels]. I saw Shelly at his club.”

“We had recorded at Chess studios in Chicago for a couple of dates, a few times,” offered Bill Wyman in a 2004 interview I did with him. “When we came into Los Angeles we went to RCA. We walked into the studio and it was too big. We were really worried. We were intimidated. We were used to recording in little places like Regent Sound. The studio was like this hotel room. And Chess wasn’t very big either. Suddenly we’re at RCA and it’s enormous. It was like Olympic (in England) later. But we solved that same problem. We thought ‘God, we can’t record in here. We’re gonna get the wrong sound.’

“But Andrew [Loog Oldham] had this brain wave and he put us all in the corner of one room, turned all the lights down, and just tucked us all around in a little small circle. And we forgot about the rest of the room and the height of the ceiling. And we just did it in this little corner.

Bill Wyman and Harvey Kubernik, 2004. (Photo by Heather Harris)

“I always thought…As long as me and Charlie could get it together, then the rest of the band could do what they’d like and it worked. And that’s what happened in the studio, and that’s what happened live. Me and Charlie were really always on the ball, always straight, always together and had it down. If we had our shit together, we got it right. What he was doing and what I was doing, standing next to him and watching his bass drum, and all that, which a lot of bass players don’t do, stupidly, once we got our thing going, and the group was there, then anything could happen. That’s all there was. There was simplicity. It wasn’t how many notes you played, it’s where you left nice holes and I learned that from Duck Dunn and people like that,” emphasized Bill.

In October and November of 1969, the Rolling Stones mixed Let It Bleed at Sunset Sound and by 1972 the creative team had established a business relationship and bioregional understanding of the studio and the essential work required to bring Exile on Main Street to fruition.

On February 15, 1972 Mick Jagger attended a T-Rex concert at the Hollywood Palladium on Sunset Boulevard after working at nearby Sunset Sound. He viewed the show from the wings along with Rodney Bingenheimer, then a columnist for GO! magazine. They had met a few times in the 1966-1969 period. Once when Rodney watched the Stones record “Goin’ Home” at an Aftermath session at RCA studios, and in 1969 when he interviewed Mick for Go! magazine.

“After the T-Rex gig Mick hopped in my Cadillac and we went to the House of Pies on Hollywood Boulevard. A girl came up to our table who I knew, looked at Mick after I made a brief introduction, and said, “You look like Mick Jagger but you’re too short to be him,” and she immediately walked away.

“I then gave him a ride home to a house he was renting in Bel-Air. During the ride I told Mick I was hanging out a lot at the United Artists/Imperial record label on Sunset and in the office were copies of double albums they released in 1971 of The Legendary Masters Series. I came back the next day and dropped off to him some of the Eddie Cochran, Ricky Nelson, Fats Domino, Jan and Dean, Ventures, and Shirley and Lee LP’s and he was really excited.”

During 1971 Dr John had cut an album The Sun Moon & Herbs. Mick Jagger sang on a track with Goodman, Doris Troy, PP Arnold, Tami Lynn, and Joni Jonz. In 1972 Goodman appeared on “Let it Loose” from Exile on Main Street.

I’ve been inside Sunset Sound many times since 1972.

In a 1997 interview with Keith Richards in San Diego as we discussed his Wingless Angels album, I asked about recording in France, Jamaica and Hollywood.

“You never point the microphone actually at the instrument,” Keith instructed in our dialogue. “You’ve got them in the corners pointing and once you’ve found those placements, you don’t really change them. One of the joys of it was that you’re not really aware that you’re actually making a record. The room is good if you know what you’re doing. Use as few microphones as possible. All the tinkering, splitting things up can never achieve. The whole idea when you play music is to fill the room with sound. You don’t have to pick up each individual instrument, particularly in order to do that. Because a band is several people playing something. And somewhere in the air of the room, that sound has to gather in one spot. And you have to find that spot. (smiles).

“Nowadays I think in a way, maybe when you write a song you are thinking, ‘Can I do this live?’ And so, in a way you add that in. You don’t know if it’s gonna work, but I guess you keep in the back of your mind is ‘We’re making a record here. What happens if they all like it and we gotta play it live?’ So, in a way that maybe in the back of the mind it sets up the song to be playable on stage,” suggested Keith as he happily autographed an Exile on Main Street compact disc to me.

Exile on Main Street billboard. Hollywood, California, 1972. (Photo by John Van Hamersveld)

During June 1972 I witnessed five Exile on Main Street tour concerts around the Southern California region.

“Exile was the end of the beginning” summarized author and musician Kenneth Kubernik. “From their impertinent debut on American television on The Hollywood Palace in June, 1964, through the next eight rough-and-tumble years, they were the luminous shadow of pop culture, glimmering blues boys who mocked convention, pissed with abandon and melded the polyphony of art, fashion, attitude and sound into a coruscating whole. Their groove cut deep and wide and everyone else was always playing for second place.

“1972 is the hinge moment, the Stones at their most narcotic, most menacing, most commercially inescapable,” Kubernik underlined. “Exile is sucking up all the air on L.A. AM and FM radio. Deejay Wolfman Jack’s got the exclusive for the first single, ‘Tumbling Dice,’ and it’s got everybody swaying to its louche beat. Can’t make out the words but Charlie’s calling the shots on this one. Their tour arrives in June; I catch five shows and its peak chaos, peak control.

“The Stones are now a going concern, a corporation with nasty habits and the industry begins to recognize that the scope and scale of rock ‘n’ roll can generate huge returns. Everybody wants to ride shotgun with the biggest circus show ever. Exile captures the slow burn, the seamless rhythm, the pride of mastery when inspiration and talent seize the moment. We were drowning in its delirious excess and nothing before or since generated such rapture. Grateful to have been present…”

The summer of 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the retail release of the Rolling Stones Exile on Main Street. A 40th anniversary edition was issued ten years ago as a 2-CD set via Universal Music Enterprises.

##

Andy Johns was a world class sound engineer and record producer. The younger sibling of Olympic Studio engineer Glyn Johns, Andy graduated The King’s School, Gloucester, England in the late 1960s. Before he even turned age nineteen he was running the dials working as Eddie Kramer’s second engineer on classic recording sessions by Jimi Hendrix.

Andy’s engineering CV credits include the debut Blind Faith effort, Mott The Hoople’s Brain Capers. His name can be found on the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers, Exile on Main Street, Goat’s Head Soup, and It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll. In John’s career, two albums from Sunset Sound he was most asked about were Exile and Led Zeppelin IV. In 2010 we talked at length about Exile on Main Street.

You had a recording history and personal history with the Rolling Stones before engineering Exile on Main Street. And you were a tape operator at Olympic Studios for Their Satanic Majesties Request sessions, and knew the band even earlier owing to your brother Glyn engineering their sessions from the beginning of their career.

Andy Johns: Well, I was aware of them when Glyn did their first demos at IBC. They didn’t even have a record deal. I remember him bringing that stuff back to the house. They soon started making records. Glyn used to live with Ian Stewart. And when my parents moved to the country on half terms, which is a four-day weekend, I would go up and stay with my brother in Epson. And there would be all this neat gear around. ‘Cause every time the Stones went to America they would buy stuff because it was obviously half the price. So I’d muck about with all that.

In fact, I named my first son William in Bill’s honor. I remember we were working at Olympic just after my son had been born, and Bill was doing an overdub sittin’ next to me. ‘So, you had a son.’ ‘I said Yes.’ ‘Well, what you call him?’ ‘I call him William.’ He said ‘What?’ ‘You heard.’ ‘Oh really…’ he got the point.

How did you get the Exile project? I know you were involved a tad earlier with Sticky Fingers and with producer Jimmy Miller. I know you worked with producer Guy Stevens on Mott The Hoople’s classic album Brain Capers.

Guy and I were very close, best man at my first wedding, first real friend I made in the record business.

I got to work with the Rolling Stones because of Jimmy Miller. I’d worked with him as an assistant engineer at Olympic, and then moved over to Morgan Studios. And they made me a full-time engineer almost instantly.

I was the only guy there. I did all the sessions that came in and got a lot of experience quickly. I did Traffic’s “Shanghai Noodle Factory” with Jimmy. And then we worked on the Blind Faith thing. He came in about halfway through on that. Mott The Hoople. Sky, Free’s live album. Then there was a Stones’ session that he brought into Morgan. The first session on “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” And it went very badly. Just horrible. They did not want to be there and there were too many of them for that little place. Al Kooper was there, I think. That was my first opportunity of working with them. And Mick was in a foul mood telling me to turn Brian [Jones] off.

I didn’t do that many sessions on Satanic Majesties … Just a few. It was bizarre. And I thought it was pretty silly stuff. You got Bill Wyman out there playing vibraphone? And some other bizarre instrument that Charlie was playing. It was just a very poor attempt to compete with Sgt Pepper’s …

Andrew Loog Oldham was still around but not very much and not much of an influence on anything. The last time he was around was during the “We Love You” and “Dandelion” recording sessions at Olympic when the cops showed up at the door and Mick was smoking a big joint. These are a couple of bobbies in uniform. And Mick was so brilliant. He puts this joint behind his back and says, “Andrew, what we need on this are two pieces of wood being hit together in unison. Like claves.”

“What about these?” offered the bobbies as they voluntarily pulled out their truncheons. So he escaped by puttin’ them on the record. And Andrew was spraying the control room to cover up the smell. At the time the Stones were having vast hassles with the cops and another bust would have been the end for them. So, it was a very narrow squeeze.

Jimmy then gets me in on Sticky Fingers. Which was about half done. The Stones has just finished putting together their recording truck. It was the first time they ever had anything. I don’t know where the money came from. The truck, it was done for Stew, if anything, because he had been so hard done by them. So, they said, “OK Stew. You run this.” And we went to Stargroves (Mick Jagger’s Berkshire mansion) and they played for a couple of days. Not very well. And then the first playback comes. And they have all these fucking hanger-ons. It was just ghastly.

So I do this first playback and Mick is leaning over the mixer at me and he says, “What the fuckin’ hell is that? I could do better than that on my Sony cassette machine. What are you doin’ here?” I thought, Christ, what a nightmare. I said, “We’ll, if you got rid of these bloody people, it’s a small space, and they’re soaking up all the sound and God knows what else. And then we’ll listen again.” And Mick says, “Oh, all right then. You’re worse than your brother.” I said, “No I’m not.”

And I waited up to speak to him the next morning and I said, “Look, obviously the Rolling Stones are far more important than my feelings. If I should go I will go right now.” He went, “No. You’re in. You’ve passed the test.”

I heard many years ago some tale where you were actually being considered to replace Bill as bassist one moment for the Rolling Stones.

I mean, during Exile in France one night Mick went, “You know maybe we should get someone else.” And I’m sitting in the recording truck, and said, “Look, you know, this probably wouldn’t mean that much to you, wouldn’t change anything, but if you get rid of Bill Wyman I’m going home.” Bill is one of my heroes.

Tell me about the Stones’ mobile recording truck?

Well, the gear in there was made by this fellow Dick Swettenham who really made the first mixes that you would recognize as a modern mixer. He had things that we now accept as normal. A pan pot on every channel. The ability to add and take away mid-range. Insert points. More than one echo send. And they look great, too. They were wrap around things. He was an extremely clever fellow. But he also built this tape machine that didn’t work. It was a fucking joke. Dick didn’t know about tape machines. He knew about electronics. Not transport. So, we were always going through hell with that. In the end I got it kicked out and we got a 3M machine. Dick put the truck together. It was his very cool stuff with four speakers in Lockwood cabinets. It could sound very nice in there but it could also be very difficult. The confined space. The camera never worked. The talk back never worked. So, you couldn’t see or talk to people. You had to keep runnin´out of the truck. “Stop!” Jimmy and I went to France with that truck.

Stew was supposed to find a house that we could all go to everyday to work. And he couldn’t find one. So, we ended up in Keith’s basement. Which of course meant the center of activity is Keith’s house. I don’t know whether Anita [Pallenberg] or Keith really liked that. ‘Cause there were a lot of people involved. They were horn players, technical people, Jimmy Miller, Nicky Hopkins, and were all there every day. And the band…Charlie is living there and Nicky is living there. So a lot of stuff for them to deal with.

Did you have to make some overt adjustments about actually recording in a Villa, a home, from what you learned at Stargroves, Olympic or Morgan studios?

I don’t know about adjustments … You just go with what is there. And you try and make it sound as good as you can. The first room I put them in was this basement which was a disaster. It just was too dead. So I moved them to another room that had stone walls. And I had Charlie and Keith in there and Mick Taylor and Bill had his bass underneath the stairs. Nicky Hopkins was in a separate room. And it was tough but some of the things came out rather well. Bianca was very pregnant at the time and I think she showed up once or twice. She had the baby during the record. Mick was back and forth to Paris a few times.

As far as microphones on hand I had the normal standard stuff. Some Neumanns, Shures, Beyers … The mikes were OK. It was just these rooms were a bit weird. Plus it had been a torture chamber during World War II. The villa was a local Gestapo headquarters when the Nazis occupied France. I didn’t notice that until we’d been there for a while and the floor heating vents in the hallway were shaped like Swastikas. Gold Swastikas. And I said to Keith, “What the fuck is that?” “Oh…I never told you. This was the headquarters.” So I guess downstairs they used to do all this dreadful shit. That’s where fires would start, the electricity would go on and off. There was just a very strange vibe down there. There were a lot of people always drifting around.

What was the food like at Keith’s villa?

This French chef would put out these lavish spreads for lunch and you’d walk out to a big table of artichokes, stuffed tomatoes, sautéed asparagus, salads and lobsters. Wonderful stuff. Big luncheon on the terrace overlooking the Mediterranean and these big yachts. It’s France. Keith would come down the steps and go, “I want a cheeseburger!” I used to kid Nicky, “Guess what? We’re having liver and onions, steak and pie.” He had a hole in his stomach. Very frail.

After two or three months the chef just fucked off. He left and Keith got these cowboys who hung around town. A big guy who became the cook who then proceeded to set fire to the basement kitchen. We then had a long weekend and Mick went off to Paris. And these cowboys stole and nicked most of the equipment, Keith’s guitars, Bobby Key’s saxophone. Another wise friendship that Keith had going. Keith then had Selmer who made the saxophones make another set brass engraved. He felt rotten about these bastards, paid Selmer and took care of Bobby, who was then better of then when he started.

Let’s talk about the songs. “Tumbling Dice.”

Obviously it was going to be great but it was a big struggle. Eventually we get a take. Hooray! I thought, “Let’s kick this up a notch and double track Charlie.” “Oh, we’ve never done that before.” “Well, it doesn’t mean we can’t do it now.” So we double-tracked Charlie but he couldn’t play the ending. For some reason he got a mental block about the ending. So Jimmy Miller plays from the breakdown on out that was very easy to punch in. It was a little bit different than some of the others. That song we did more takes than anything else.

“Rocks Off?”

It went on for ages. When Mick came back from Paris for the first time he seemed happy with the sound. And Keith would sit downstairs and at one point he sat there for 12 hours without getting out of his chair just playing the riff over and over and over.

And then one night, it was very late, four or five in the morning, Keith says, “Let me listen to that take again.” And he nods off while the tape is playing. I thought, “Great. That’s it. End of the night and I’m out of here.” So I go back to my place where I was staying. [Horn player/arranger] Jim Price and I had this villa. It was pretty spanky. I’m tellin’ you. A half an hour drive. I walk in the front door and the phone is ringing. I pick it up and it’s Keith. “Where are you?” “Well, I’m obviously here ‘cause I answered the phone.” “Well you better get back here, man, ‘cause I have this guitar part. Come back!”

And I returned and it’s now six in the morning and he played the counter rhythm guitar of “Tumbling Dice” which was another Telecaster track, a second rhythm track, the whole thing just came to light and it just knit the whole thing together. That was one of my favorite tunes. Keith used to sleep with his guitars.

It was a very busy mix. It was very difficult to mix. At Sunset Sound I tried mixing it a couple of times and it wouldn’t work. On the last batch Mick called up and said, “Come back. We can’t beat your mixes.” I mixed about another 12 songs in a marathon session. I would just leave the booth to have a piss and just go back in the room and that was it. For some reason I brought “Tumbling Dice” up and it just started to work. Sometimes it happens that way.

Mick Jagger at Sunset Sound, 1972. (Photo by John Van Hamersveld)

You had been in Sunset Sound in Hollywood before and worked on some early Led Zeppelin albums.

Yes. I had been in Sunset Sound and was very enamored of the tapes that I would get from Sunset Sound. I really liked the way Let It Bleed sounded that was mixed at Sunset Sound. And I really liked some other stuff that my brother had mixed at Sunset. That’s why when I took Led Zeppelin there and they changed the room, and I mixed all of Zeppelin IV and it sounded like shit when I got it home. But I still knew that had to be me and not the place.

So, I remember talkin’ to Keith in his basement in France. Just Keith and I and I said, “Look, the next step is that we’ve got to go and finish the overdubs and mix. Why don’t we go to Sunset?” And they worked there before. So, “Yeah, all right.” And of course, I loved LA. 21-year-old English guy, and I had done a couple or three projects there. So I knew people and chicks eventually. “Yeah. Let’s do that then.”

We got to Hollywood. It was taking pretty slowly and I was taking a lot of time to get mixes. But they were coming out quite well. We were doing overdubs at the same time. And the Musicians Union guy came by to try to bust us.

The Union said if you were foreign musicians you had to give one per cent of the record to the Union. So they warned me at the front desk, “He’s here again!” So, we’d scrabble around and put everything away and then he’d walk in. I’d pretend I’m just mixing. And in those days, I mean, nobody took four or five months to mix a record. [laughs] You did it in a week. So he was very suspicious. I remember we did go over to Wally Heider studio down the street, and he came in to try to bust us again. And Bobby Keys was actually playing tenor saxophone. And he knew what this guy was. And he comes runnin’ out of the studio into the control room and the door on that control room opened right onto the street in Hollywood. And Bobby has got his sax over his head and he’s gonna smash his brains in. And the guy is running up towards Hollywood Boulevard with Bobby shouting and screaming at him with the sax still raised above his head. And I saw them go round the corner and I didn’t see Bobby again for a couple of weeks. [laughs] I think he went to a bar and just forgot what we were there for [laughs]. So we never saw this guy again. Bobby put the fear of Texas into him.

Did you ever have any concerns about taking basic tracks mostly done in France at Keith’s villa for six months at Nellcote and then transferring them to another room like Sunset Sound in Hollywood? I know years earlier during Between The Buttons there was some slight loss of tape generation during multiple master tape transfers between RCA studios and Olympic. Although I know that was not the case with Beggars Banquet an album your brother engineered and then mixed at Sunset Sound.

I had no worries or concerns about fidelity. In actual fact, it worked to my advantage. Because they had this bloody great Ampex machine that had very high tension on it. And because of this dodgy machine that had been in the truck now the tape was being smashed up against the heads. And it sounded in actual fact a little better. It was much easier to deal with. But you know you don’t think about that. There were certain places…

There used to be a theory, “If you record at Criteria in Florida you can’t mix at Record Plant,” and stuff like that. I remember Stephen Stills tellin’ me that in the men’s room at Record Plant once. And he was right. “Just go on a plane and go back to Criteria.” So, I did. No, that was not really an issue. The issue was trying to retain a balance of continuity.

Because there is Mick and Keith, and Jimmy and Andy, and then there’s Marshall [Chess] and everyone, you know, is trying to get it done but in different ways. So it got a bit silly. But the transfer aspect was done as per normal. You do the basic track, get the arrangement sussed out and do basic track. Then you look for other ideas which quite often appear almost like on their own. They just come out of the air.

I was still learning on Exile so I wasn’t influential really at all about anything except for perhaps choice of song once or twice. “This shouldn’t be a single.” They had been making records for quite some time. Mick saw himself as sort of the producer. Jimmy Miller was on his way out so Mick would be around for everything. “Let’s put the chicks here.” “Let’s have Jim [Price] come up with something for this.” Somewhat of a martinet. But no problems, and in the end, it was pretty much Keith’s final decision. That’s why it was a bit of a mess. Nobody was quite in control because they had given up on Jimmy a bit.

Tell me about Jimmy Miller as a producer and mate. Spencer Davis once said, “Jimmy Miller was the first genius producer I ever worked with.”

Well that’s easy. Jimmy was an extremely talented man. His main gift I think was his ability to get grooves. Which for a band like the Stones is very important. Look at the difference between Beggars Banquet and Satanic Majesties. He put them right back on the rail so he was quite influential then and came up with all sorts of lovely ideas for them. In fact that’s him playing the cowbell at the beginning of “Honky Tonk Woman.” He sets it up. He was somewhat of a frail individual and they got to him like they got to everybody. Sooner or later you lose your mind.

By the time we got to Exile on Main Street they weren’t really listening to him anymore so he felt a bit like a fifth wheel. He was being squeezed out a bit and I was watchin’ that go down.

Jimmy was mad keen and sort of half way in control of Sticky Fingers but his grip was slipping a bit. You know, Mick and Keith back then could be pretty fuckin’ ruthless. It’s a defense mechanism because people forget how big a deal they were so everybody and their uncle is trying to grab the hem of their coat. They always want something, you know. “Listen to this song. You should really do this song.” “I’ve got this great idea for a hotel. Give me the money.” Constantly. And the dope dealers and the groupies. So I guess that hardens you to a certain extent. I know it has to me a little bit.

On Exile Keith would play after the fact. We’d have some time and Keith would say, “I want to redo the bass.” In front of Bill, you know. They were really cruel.

The guitar contributions of guitarist Mick Taylor were apparent to you over your working relationship with the Stones in the studio. And he received a co-write on the track “Ventilator Blues.” You have said it got quite steamy in Keith’s basement ‘cause there was one small window and an electric fan blowing in the summer. So you all had the “Ventilator Blues.”

Mick Taylor in the studio in France or Sunset Sound was just a shining light. As a person somewhat taciturn. When he plays his guitar and we’d do 100 takes on something he would come up with something slightly different every time. Faultless. Every once in a while he’d drop a note. I mean, that’s expected. His slide playing. He’s put a bottle on his little finger and then he’d do chords with the rest of his hand. So he could do both at once. Usually it’s a separate deal but that was part of his style. His sense of melody was unbelievable.

Every time I knew it was Mick Taylor I’d be sitting at the edge of my seat. He was wonderful but became discontent with his situation. On the 1973 tour of Europe I spent quite a lot of time with him and he would say, “They won’t let me write any songs. Anytime I have an idea I’m blocked out.”

Later I put Mick onto Jack Bruce who was a good friend of mine and still a huge admirer of him, then and still now. They formed the Jack Bruce Band and Mick Taylor Band with drummer Bruce Gary, who would be a good friend for years in LA before he was in the Knack and afterward.

The Rolling Stones at Sunset Sound Studios, 1972.

(Photo by John Van Hamersveld)

Did you have any specific philosophy on recording vocals during Exile?

That’s a funny question and I don’t want to be rude. If you’re gonna do vocals you put the microphones up that you are familiar with—a Neuman 87, that’s what I used on Mick and Keith. Then you can put a compressor on it and then you record. If it’s not working you search for other ways of doing it. It usually works.

Mixing of the echo chamber at Sunset Sound.

We didn’t use it all that much. There had been a fire and when it was re-built it didn’t sound quite the same. But I might have used it on some stuff. I was mostly using EMT 140 plates. On the “Rocks Off” mix we put on an echo effect on Mick’s voice and got lucky. It ties together.

Overdubs were not a problem. Any kind of overdub activity, except for “Happy,” where Jim Price was in charge of horn arrangements. That was his responsibility. And Bobby Keys, who has a mathematical mind, would beat you at chess in three moves. That kind of cracker white trash persona that he puts on is just a front. Born the same day as Keith. I remember a birthday party and got in a lot of trouble for that.

You did?

Well…I started a cake fight. And then Keith was in the bathroom, one of the old Apple Records houses, big old house, Beatles, and Keith was trying to take a dump or something, and Bobby and I went down the corridor and I had a big piece of cake. And we’re banging on the door and he won’t open it. And Bobby said, “You know, we shouldn’t do this.” And I went, “Fuck it.” And kicked the door in and Keith runs over to the sink and I got him with the cake. Just rock ‘n’ roll fun [laughs].

And I had given him this huge Nazi dagger for his birthday. The first thing he got, you know. So I show up the next day and he’s sitting up with his feet on the kitchen table with this dagger sticking out of his belt and he gives me a lecture on behavior [laughs]. “You can’t do that sort of thing. It’s really not right. Come on, man. This isn’t your house and throwing cake around.” This coming from Keith. OK.

And the legendary pianist Nicky Hopkins is all over the Exile album.

Nicky is on everything. He was the best and the greatest. God bless Nicky Hopkins. He added so much to that band. Sometimes you wouldn’t really notice it. But if you take the piano out then the house of cards collapses a bit. He was always coming up with gorgeous little melodies. Earlier, “She’s A Rainbow.” That’s Nicky. Of course he was doing a lot of things like that. Plus he was extremely rhythmic. People don’t remember him for being rhythmic. But he was.

When people think of Nicky Hopkins they think of his right hand. But he would make the groove happen sometimes. If he took him out, “Oh, what happened here?” Which is normal. If they are listening to him they are gonna play around him. Or with him. And if you take one of those elements out “What happened here?” It’s music. See. That’s how it works.

Jim Price and I went into a Nice France toy store. They had Chinese fireworks. Big M80 things. Nicky was in this basement room all on his own with the piano and he would sit for a long time with people talking, doing arrangements and he would be head bent over the piano and never say a word and wait. One day Jim Price suggests to toss a firework into his room that had a cement floor and stone walls, iron grill in basement, “I’m not doing that.” “You have to do this.” I was very gullible and very quickly tossed it through a tiny window. It was fuckin’ loud. Boom!

Only time I ever saw Nicky really angry. ‘Cause he was meditating. He ran up the stairs, “Who the hell?” Jim made me do it like we were kids. So I miss Nicky dreadfully, he was one of a kind. Never gonna happen again.

What was the first song actually completed for the album?

“All Down The Line.” It was the first one that was finished ‘cause we’d be working for months and months. Mick got very enamored. “It’s finished! It’s going to be the single!” I thought, “This isn’t really a single, you know.” I remember going out and talking to him and he was playing the piano. “Mick, this isn’t a single. It doesn’t compare to ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ or ‘Street Fighting Man.’ Come on, man.” He went, “Really? Do you think so?” I thought, “My God. He’s actually listening to me.” [laughs]. And then, I was having a struggle with the mix I thought was gonna be it. Ahmet Ertegun then barged in with a bunch of hookers and ruined the one mix. He stood right in front of the left speaker with two birds on each arm [laughs].

I told Mick, “I can’t hear it here. If I could hear it on the radio that would be nice.” It was just a fantasy. “Oh, we can do that.” “Stu, go to the nearest FM radio station with the tape and say we’d like to hear it over the radio. And we’ll get a limo and Andy can listen to it in the car.” I went, “Bloody hell…Well, it’s the Stones. OK.”

So sure enough, we’re touring down Sunset Strip and Keith is in one seat, and I’m in the back where the speakers are with Mick, and Charlie is in there, too. Just because he was bored [laughs]. And Mick’s got the radio on and the DJ comes on the air, “We’re so lucky tonight. We’re the first people to play the new Stones’ record.” And it came on the radio and the speakers in this car were kind of shot. I still couldn’t tell. And it finishes. Then Mick turns around. “So?” “I’m still not sure, man. I’m still not used to these speakers.” “Oh, we’ll have him play it again then.”

Poor Stu. “Have them play it again.” Like they were some sort of radio service. It was surreal. Up and down Sunset Strip at 9:00 on a Saturday night. The Strip was jumpin’ and I’m in the car with those guys listening to my mixes. It sounded OK. “I think we’re down with that.” So then we moved on.

I also heard one time at the legendary Lewin Record Paradise shop on Hollywood Boulevard that carried all the UK import albums that there was another rumor you left the project or split the scene around the later stages of mixing but then later requested by Mick to come back.

I went home for Christmas and thought they were not going to ask me back. In February ’72 I was in Malibu doing pre-production on this Jim Price solo album and somebody slipped me a hash cookie. And I don’t like grass and hash. It makes me very paranoid. And it was as cookie. “OK. I’ll eat that.” And then: BOING! “Oh my God, what’s in this?” I went into my bedroom and was so paranoid and got a chair and stuck it underneath the door knob so no one could get in. The phone kept ringing. Jim Price said, “It’s Mick for you.” “Oh man, not now, Not in this state.” I pulled myself together. “Hello Andy.” “Hello Mick. I’m sure you’re not calling just to say hello.” “Well, no….Not really.” That was fairly honest. “Those mixes that you did we just can’t seem to beat them. Would you like to come back and finish the record?”

I was very happy about that. Mick was unhappy about how long it had taken me to do the first five mixes. And thought I was losing it or something. Jimmy Miller’s other engineer guy was Joe Zagarino who died shortly after all these events. And they worked with him for a bit finishing up with little bits of overdubs. Nothing important. And trying to mix. And he couldn’t pull it off. It was tough stuff to do. I had a feeling I was the only guy who could have done it at that time. So Mick and I got together the next day at Wally Heider’s and it wasn’t comin’ off there at all. I didn’t like it. He was fairly patient.

We went out to some club one night on Sunset Boulevard. It was Soul’d Out that became Club Lingerie. We walk in the door and it’s all black folks during “Super Fly.” The music stops and it’s every face turned towards us, we’re the only white people in the building and I thought, “This is it.” [laughs] And then they recognized who he was and we had a grand old evening.

It was around the corner from Wally Heider. I said, “Look, this isn’t working. We’ve got to go back to where we did the stuff that we like at Sunset Sound.” So we went back to Sunset and Mick said, “I’ve been working on this fuckin’ thing so long. Here are the tapes. I am leaving them with you. Get it finished as quick as you can.”

And Jimmy Miller is there. He wasn’t that involved but just kind of helpful. A bit of moral support. Dear old Jim. So I finished it all up in this one marathon session.

What is this story I’ve heard over the decades that some geezer, before downloading and sound file sharing were fashionable buggered off with a master tape of Exile On Main Street right under your nose at Sunset Sound. Did it happen?

When I finished the album I then made a 7 and a half inch IPS copy for the band and left it out front at Sunset Sound in the traffic office. Then a guy shows up like a messenger and picks up the copy. “That’s for me. I’m delivering it to the boys.” Some stranger. It never got bootlegged. He kept it for himself. I was a bit freaked out about it ‘cause I would be the one who got it in the neck.

You also mastered the original album in Hollywood.

I mastered it on Sunset Boulevard at Artisian, in the same building where CNN stands. My only concern was that the only time I was gonna hear it was in the mastering room. And you had to be able to take it home and listen to it. “Yes, I see now.”

In those days we didn’t used to spend a lot of time in mastering which of course is as important of the procedure as anything else. ‘Cause you can ruin it. I think it came out OK. There is one song at the end of side, we were doing vinyl albums then of course, the last inch is very difficult ‘cause the diameters are getting smaller and smaller on the disc and got a bit distorted.

You know a lot of people like and worship Exile. What is the magic of the album? I see and hear it as a frozen time capsule with sonic elements imported from France and then prepared and served from Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard.

Well, I think they were at the height of their powers in a way as far as rock ‘n’ roll goes. Those pop singles and albums they made in the sixties were stunning. But with Exile, ‘cause it’s mostly blues-based stuff. “Stop Breaking Down” is probably my favorite track. I remember getting Mick to play harmonica on that. It did not seem like it was finished. My brother [Glyn] had recorded earlier. I said, “We’ve got to use this” because Mick Taylor plays some gorgeous lines and I’m very sure that it’s Mick Jagger playing the rhythm guitar as well. That’s why it’s a little choppier.

It’s an intangible. Exile just turned out to be a great collection of music. And I think it was good that it was a double album. Some people say it should have been a single album but you get the feeling of what they were going through of the time and the confusion and the angst and the joy and the drugs and they moved out of England. There were a lot of emotions.

It’s also Hollywood, summer 1972 on tape. Sunset Strip when it still mattered.

Well, yeah, but it’s not as if we were having these big parties and orgies and things. It was heads down and work.

© Harvey Kubernik 2002

Tower Records. Los Angeles, 1972.

(Photo by John Van Hamersveld)

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and Neil Young Heart of Gold during 2015.

Kubernik also authored 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with DA Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are included in The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. Kubernik is active in music documentaries. Harvey served as a Consultant on the documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood.