Interior Design

Oscar-Winner Jeremy Irons on His Irish Castle and Antiques Obsession

The actor’s lifelong passion for design and collecting is reflected in his painstakingly renovated 15th-century home.

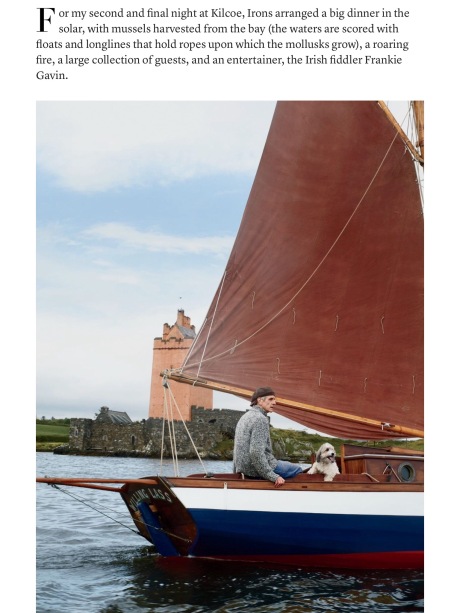

Jeremy Irons, with his dog, Smudge, at Kilcoe Castle, in Ireland. Top: Irons and a team of workers spent six years restoring the 15th-century structure, where, he says, they did “everything from scratch.”

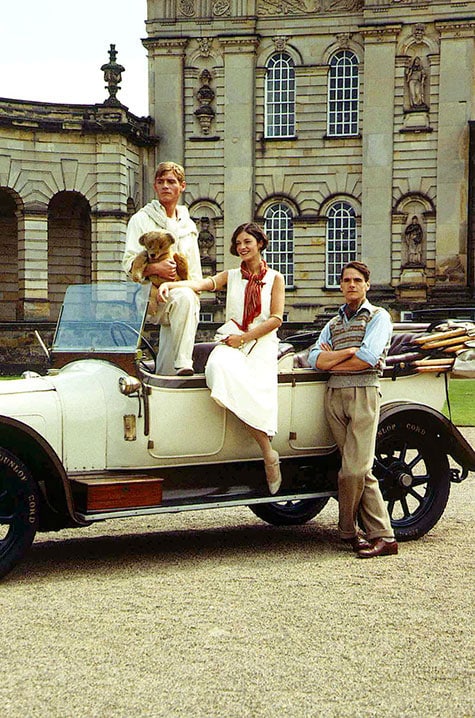

First comes the dog. Then, Jeremy Irons appears, filling most of the door frame of the small mews house in West London that serves as his pied-à-terre in the city. “Smudge! It’s a friend,” he calls out. Tall, with an innate physical elegance, Irons looks pretty much as he did when he shot to fame playing the beautiful young painter Charles Ryder in the 1981 British television miniseries Brideshead Revisited, or Claus von Bülow in his Oscar-winning turn in the 1990 Reversal of Fortune. Just a few more lines and sporting a slightly military mustache, grown for the role of James Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, which moves from London’s West End to a run at the Brooklyn Academy of Music from May 8 through 27.

His sympathetic portrayal of the family patriarch alongside Lesley Manville in the Richard Eyre–directed production has garnered glowing reviews from the British critics. “It’s a marathon of a play,” Irons says wryly. “You have to keep fresh and interested, but that of course is an attraction.”

Nevertheless, on a chilly London morning in the middle of an eight-performance week, Irons seems happy to turn his attention away from acting and talk about his adult-life passion for decorating and furnishing his homes. (Quite often, as he tells stories of finding a chemist’s balance in Bucharest or a group of carved musicians in Morocco, he gives the impression that he remembers his movies purely for the interesting object-spotting locations they afforded.)

Irons’s London home is, he says, much like his other homes, just smaller. It is filled with color, with cream-of-tomato and blue-green walls and fabric hangings found in Afghanistan, which form a border around the living room cornice, framing rough hessian blinds. An eclectic assortment of furniture, much of it picked up at auctions or found in the street, and walls full of art (some of it by his photographer son, Samuel Irons) create a cheerfully warm and relaxed environment. Does his wife of 40 years, the actress Sinéad Cusack (who arrives home mid-interview), take part in the decorating? Irons thinks for a moment. “Not a lot,” he says. “She doesn’t have the passion I have.”

For nearly two hours, Irons talks to Introspective in fluent paragraphs about that passion, along with his belief that inanimate objects absorb the energy of their environment and about managing the restoration of Kilcoe Castle, his 15th-century home in southwestern Ireland.

Did you grow up in a family that was interested in art or antiques?

Not really. My dad was an accountant and my mum a housewife who raised us, as was often the case in those days. We lived in a house in St. Helens on the Isle of Wight which was, I think, a converted stable. It was just after the war, and unless you lived in a house that had come down to you over generations, people didn’t really think about furniture and pictures. Ours were pretty ordinary, prints and so on.

I think it was when I started at theater school in Bristol that I first bought some paintings. I picked up about ten, did an exhibition at a framer’s shop and sold them for a modest profit. After that, I found a collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Playbills and bought the lot. I slowly framed them and sold them. I still have one or two. My drama school fees were paid by my father, but my living wasn’t, so it was a way of generating a little income.

Then, I started going to the auction house in Bristol. It was a wonderful time. I don’t know why, but the antiques business was just flying, and there was so much interesting stuff about. If there was something I loved, I’d buy it and do it up and sometimes sell it. Often chairs — I’ve always been attracted to them.

Why chairs?

Chairs touch the most of you. In beds, you often replace the mattress, but chairs wrap around you, and if my theory — which I stand by — that inanimate objects absorb energy is right, the chair is the most likely piece to do so.

How much restoration of chairs or other pieces do you do yourself, and how did you learn that skill?

I can do a bit, but I’m not a carpenter. If something needs really fine work, I will find someone. But I learned a lot just by doing. Our first house was in Islington. We didn’t have much money, and I bought most of our furniture at auction. Then, we moved to a lovely Victorian house in Hampstead, and I learned to do plumbing and electricity and more serious woodwork. You know, as an actor, you often have the time!

I remember collecting these wonderful tiles that used to be around fireplaces, and I made a little shower room filled with the tiles in that house. I found an old cast-iron range in my brother-in-law’s bookshop on Kensington High Street which I really loved. It smoked, and I experimented with a hardboard cowl to see if I could stop that. It worked, so I had it made in metal. I’m still sad that, when we left the house, I didn’t take it.

Then, we moved to a Regency house in Oxfordshire, where we still live, and I seriously had to look for furniture for that. I found a wonderful auction house in Newcastle and remember having a really good morning there, buying a French screen and wonderful wingback chairs — all of which we still have. I’m attracted to a Georgian aesthetic, and that’s what I was aiming for with the Oxfordshire house. I don’t like the heaviness of Victorian-era stuff.

Did you hunt for furniture when you were on tour or on location?

Yes, of course. I remember going to Stratford when I was with the Royal Shakespeare Company and living in a lovely house on the River Avon. Next door was a farm and a barn, and the chap who owned it would find furniture and ship it to America. I would keep going in and saying, “No, you’re not sending that.” I bought loads of really useful things there, like small cupboards.

When I was doing a Bristol Old Vic schools tour of the West Country, around fifty years ago, I found an abandoned house, and at the top of the shed were bedposts for two four-poster beds. I brought them back on the train, and when we did the house in Oxfordshire some years later, I gave them to a carpenter and asked him to make a bed with them.

I love going into traditional hardware shops in countries with different histories to us. I bought a mop in Greece made of wood and with looped rope that you can pull up to squeeze out the water. It hangs in our kitchen, and people often can’t work out what it is.

I hunted at home, too. I had an ex-post-office van, and I would stop at every skip [dumpster] and see if there were interesting moldings. I have always been a sniffer out of unconsidered trifles. Once, I discovered that an old house on Hampstead Heath was being pulled down, and there were these hexagonal white Carrara marble tiles with slate joinery that were going to be destroyed. I listened to a radio review of The French Lieutenant’s Woman while chipping them out. I still have them in the conservatory I built. In fact, I haven’t yet used them all.

“If something needs really fine work, I will find someone. But I learned a lot just by doing. . . . You know, as an actor, you often have the time!”

I’m not sure how you have found time to have an acting career.

Hah! It’s true that I’m always on it. Sinéad would tell you about us going out to dinner in Paris when I saw a skip near the restaurant. I looked in and saw a nice copper bowl — an old laundry bowl that would sit over a fire. I had exactly the place for it in an outhouse in Oxfordshire! I pulled it out, all greasy and dirty — we were nicely dressed — and I brought it to the restaurant. The lady who takes your coats took it rather gingerly.

What about paintings? Did you collect those too?

Yes, and that was fun, because after a while, I was earning well, and I bought some lovely pictures. I tend to be attracted to paintings done between 1880 and 1930, mainly of women.

Sometimes, I would meet friends in different cities, and we would go looking for paintings and antiques. I remember being at the Marché aux Puces at the Porte de Clignancourt, in Paris, and nearly spitting with rage because it was all so overpriced and uninteresting. Then I saw, leaning against a shop door, an oil painting of a maid sitting at her embroidery. In the background, you could see a little iron single bed and a table with a daffodil in a glass. Her face was wonderfully painted, and she said, “There you are. I’ve been waiting all fucking day!” I knew exactly where it would go. I put it up in our bedroom, and she yelled at me: “Get me out of here, I don’t want to be in this bedroom!” So, I put her in the other place where the light was right, in the sitting room, and she said, “That’s better.” She still sits there now.

You own a castle in Ireland, which you restored. How did that happen?

Sinéad is Irish, and before the castle, we bought a little cottage in Ireland that was supposed to be a lock-up-and-go kind of place. We really rebuilt it, because it was falling apart. And that was great, because I went out into the Irish countryside and found some wonderful old things — settles and fire surrounds — and did the cottage in indigenous bog-Irish style. I came across a wonderful book about Irish furniture [Irish Country Furniture 1700-1950 by Claudia Kinmonth], and learned a lot from that.

During that time, I knew of the castle, which had been ruined since 1603. I thought, Someone is going to buy it and mess it up. I was getting bored with film work, so I thought, Why not me? It’s a military building, very male, very hard. How could I make this a nice place to be? It was such fun. It gave me opportunities I had never had before with a home.

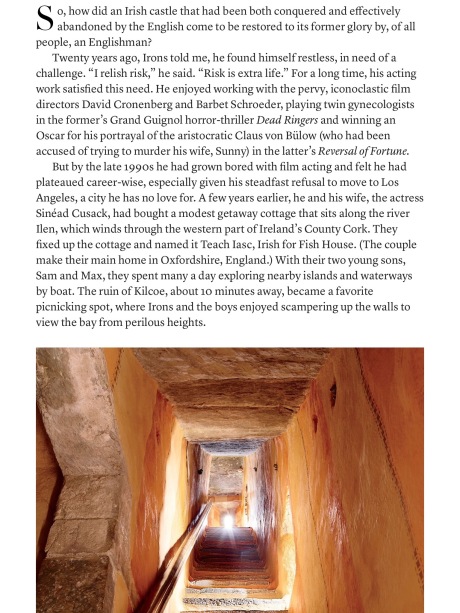

We did everything from scratch. It took six years, but the first three years was the main stuff: rebuilding walls with a green sandstone I found — after looking through so many quarries — in the Forest of Dean [in Gloucestershire, England]. I drove it in my trailer all the way back to Ireland. Then we cut the windows and repointed the castle to a hand’s depth. Inside, we found that the mortar that had been put there in 1450 was still moist. The walls all the way round the castle were nine feet thick at the bottom.

After the repointing and cleaning, I had people going around almost with magnifying glasses, looking for striations and filling them with lime mortar. It looked absolutely beautiful. Then, we had our first major storm, and the water poured in. I called a mate who is a mortar expert, and he said, “You have to render all the walls with lime mortar.” So, now my green stones are all covered with render, and I needn’t have spent any time on the searching!

Did you manage everything yourself? Did the restoration process ever feel overwhelming?

No, because it wasn’t a twenty-four-hour-a-day thing. We’d start at seven-thirty in the morning and knock off around five-thirty. It’s a bit like being a film director: If the weather is bad, how do you keep everyone busy and employed? A lot of the workers were musicians, and I told them, “We are doing a jazz riff on the medieval. We have to remember where we are and can play with it.”

I’m quite particular. When they did the castellation, I thought it just didn’t work. I climbed up thirteen floors to tell the guys, and the supervisor said, “The trouble with fucking actors is the rehearsals!”

Did you know what you wanted the interior of the castle to look like?

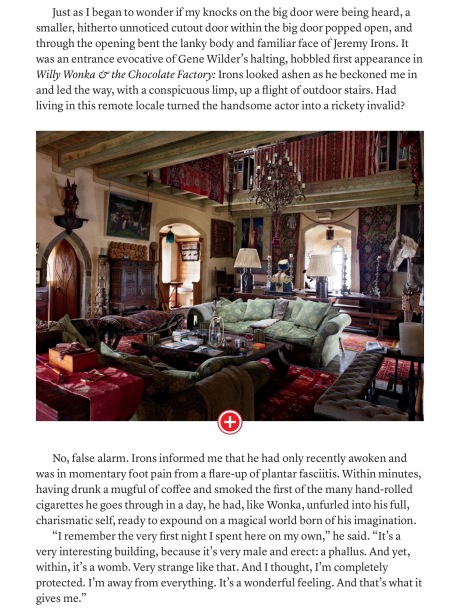

Originally, I thought I’d repair all the rooms and do the walls, which I wanted to be rough, with all the kinks retained. I had stayed in a ryokan in Japan and loved the way it was so peaceful, with nothing to distract the eye. I thought maybe that’s what I’d do: keep it all glass and modern and empty. But then, I just let it evolve and talk to me as we were working on it. And it evolved into a cluttered interior! There is a sensibility that is the same in all my homes — different objects that I love, a lot of different colors.

I saw the movie Women in Love around 1969, when it came out, and one of the characters lived in a converted barn. I thought, That’s what I would like. And in the back of my mind, that image has always been there when I’ve done a house and collected the furniture.

How carefully did you plan each room? Or did you just try out different pieces?

A bit of both. Sometimes, I knew exactly where certain things would go, like a life-size wooden horse I found in an antiques shop in Stow-on-the-Wold, in Gloucestershire. It was a lot of money, and we were just starting the castle. So, Brian Hope, who has looked after the Oxfordshire house, and I went for a drink. I said, “If we use the horse as a mold, we could make fiberglass ones for people’s gardens and sell them.” And Brian nodded and said, “Good idea.” Of course, we never made a single one, but it justified the purchase. I knew I’d put him to stand and watch the door into the main living room — the way white horses would face the enemy — and frighten away those who shouldn’t be there.

For our bedroom, which is under the roof, I knew what I wanted from a time when I was filming The Man in the Iron Mask in a farmhouse in Le Mans. There was this room that I loved, like an upturned boat. I went there with Brian, and we took all the dimensions and rebuilt the room like that.

I’d always wanted a hanging bed, and I found local craftspeople to build it and the chests against the wall, which are built on a slant. There is willow work on the back of the bed, around the bath and even on the ceilings which was done by a local woman. So, all of that was quite thought out.

Other things were just serendipitous, things I found while traveling, like paint tins from the Skoda factory in Bucharest that are now lamp bases, or cushions and rugs and fabrics I bought while filming in Nepal.

Among all these wonderful discoveries, are there particular pieces that mean something special to you in any of your homes?

It’s difficult to choose, but there is one barrel-backed armchair I bought in Bristol. It’s probably Georgian, like a wing chair but with a rounded back covered in panels. Under the seat there was a commode, which I did away with when I got it reupholstered. It’s in my bedroom in the country, and it’s lovely to sit there with a cup of tea and look out of the window and think about the day.

https://www.1stdibs.com/introspective-magazine/jeremy-irons/

You must be logged in to post a comment.