Tolkien’s artwork, rather than his writing, was my first gateway to Middle-earth; so Jeffrey J. MacLeod’s and Anna Smol’s recent article “Visualizing the Word: Tolkien as Artist and Writer” (Tolkien Studies, volume 14) is of particular interest to me. The authors propose a reevaluation of Tolkien’s imaginative and writing process to recognise the integral role that Tolkien’s own practice and knowledge of visual art had on his stories. They make four core arguments:

Tolkien’s artwork, rather than his writing, was my first gateway to Middle-earth; so Jeffrey J. MacLeod’s and Anna Smol’s recent article “Visualizing the Word: Tolkien as Artist and Writer” (Tolkien Studies, volume 14) is of particular interest to me. The authors propose a reevaluation of Tolkien’s imaginative and writing process to recognise the integral role that Tolkien’s own practice and knowledge of visual art had on his stories. They make four core arguments:

- Tolkien used sketches to help him draft the stories – sketches which often altered descriptions or moved the story forward.

- Tolkien’s knowledge of visual art, and his ability to think like a painter, affected his style of prose and choice of description.

- Tolkien’s visual imagination contributed to his calligraphy and invented alphabets, adding depth and expanse to his world-building project.

- Tolkien’s practice of art had an impact on his theories of fantasy.

To quote the authors, “visual image and the written word merge in Tolkien’s creative work” (115) and thus, “Tolkien’s art and his visual imagination should be considered an essential part of his writing and thinking.” (116)

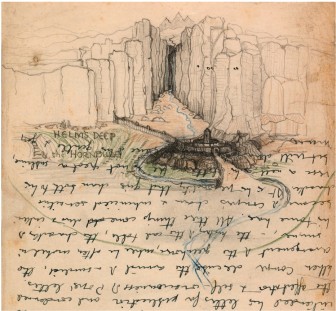

In a fascinating section of their essay, building on Hammond and Scull’s seminal work on Tolkien’s art, Smol and MacLeod discuss the ways in which Moria, Helm’s Deep, Orthanc, Minas Tirith and Cirith Ungol were all conceived and revised through Tolkien’s use of drawings, diagrams and maps. For example, interspersed between the original handwritten text (first in pencil, overwritten in blue ink as was Tolkien’s custom) one finds sketches of the Tower of Cirith Ungol, forcing him to write around his drawing as it intrudes from the margins to almost halfway across the page. As the authors point out, it is unlikely that a blank space was reserved for a picture to be added later – rather the drawing came in the midst of writing and in fact informed the latter; indeed the descriptions of the Tower come afterwards.

This method explains not only why Tolkien’s place descriptions are so realistic, but also why they are so well suited to, and so regularly inspire, artistic renditions (in all their variety). Tolkien’s writing seems to invite readers to participate in a visualising process that he engaged in himself (Barbara Strachey’s ‘Atlas’ is an impressive example of this). Smol and MacLeod explain, “Tolkien not only had to see the landscape in his mind’s eye, he had to see it with his physical eye. Like writers who write to discover, Tolkien also draws to discover.” (117)

Reading this reminded me of two formative experiences as a student many years ago. The first came a month into the start of my project while attending a research seminar at my university. After a month’s initiation we had already experienced enough of academia to feel quite lost and confused. (It’s a rite of passage, is it not, to wonder if every other concept or scholar must be essential to one’s project, ending up far down a rabbit-hole before realising it leads nowhere.) The seminar was supposed to help streamline our core arguments, but before anything was said we were each handed a cellophane packet with an assortment of lego pieces and two lego men. We were then asked to ‘build’ our theses – as unformed or unrealistic as they were at that early stage – and then explain our constructions to a colleague. We all had similar lego pieces, but used them to represent completely different things. Having to express concepts in this unconventional way did to some extent help release ideas that seemed trapped when thinking of them solely as words, or forced a level of clarity and brevity that could too easily be circumvented with writing. I don’t remember anything else from the seminar, but that I think was an interesting exercise.

Fast forward years later to the final months of the dissertation – most chapters had been written, the end was finally in sight, but an enormous obstacle seemed to block my path. The thesis rested on a theoretical critique I made back in chapter 2; it sounded convincing enough, but deep down I knew there were unanswered questions. What started off as niggling doubt transformed into a mental beast as the dread of having to confront it grew. After several aborted attempts to resolve the problem by thinking and writing, I turned my notepad sideways and started to draw ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ was. Slowly, miraculously it felt at the time, ideas connected and flowed – along came the moment of epiphany that until then I had begun to think was a mythical notion. Both excited by the ‘discovery’ and fearful that it might fly away I hurriedly tried to catch the messy diagrams and sketches in written form. That relief and sheer joy of ideas coming to fruition continues to motivate me, despite the ditches I have to scramble through in between.

Reading Smol and MacLeod’s article and reflecting on Tolkien’s writing process has reminded me of the alternative creative practices that can be used to plant or nourish our ideas. There is of course another important component to this, and that is persistence and time. Another topic for another day, but it’s enough to say here that the creative process is accumulative, one that needs patience and consistent building. Sometimes the breakthroughs will be gradual developments; sometimes they will be sudden, apparently coming from nowhere, but most likely even those moments come from subconscious connections that have been made and archived over time.

In my case, some of my diagrams (basic though they were) made it into the final thesis; so integral had they been to the overall argument I felt they should be there as an aide for any readers. What I find remarkable, therefore, is that Tolkien was so disciplined in not including a lot more of his own drawings in his final manuscripts. Take for example the Tower of Cirith Ungol: As Smol and MacLeod point out, Tolkien spent quite some time and effort in working out its size and sketching the dimensions of the tiers in relation to each other. But, “once he had done that…he only needed a few specific details to convey a sense of the scale of the place in his writing.” (118)

Despite their sparsity in the final print, we know from Tolkien’s letters that he was still very keen to include some visual items, and was particular about them too. For what its worth, I would have loved to see more of his maps, artwork and calligraphy in the published stories, and I am glad he insisted on including those that are there.

However, this sparsity is arguably a blessing – not only imposed on him by the publishers but very possibly intended by Tolkien too. The article reminds us that Tolkien wanted each reader (or hearer) of his stories to give the words he used “a peculiar personal embodiment in his imagination” (JRRT, Of Fairy Stories, 82, quoted in MacLeod and Smol, 126). Tolkien called this his “invitational” style, while Smol and MacLeod describe it as his “painterly” style: that is, wanting the spectator to participate in completing the picture with their own interpretations. This approach to fantasy and Tolkien’s concern that the spectator should be allowed to participate in his art is reflected in his own drawings of scenes in The Hobbit and The Lord of Rings, which are often of landscapes where we still have to imagine the characters ourselves. To depict a scene too explicitly can close the process of imagination for the ‘spectator’ (how interesting, as noted by the authors, that Tolkien should use the word spectator rather than reader).

However, this sparsity is arguably a blessing – not only imposed on him by the publishers but very possibly intended by Tolkien too. The article reminds us that Tolkien wanted each reader (or hearer) of his stories to give the words he used “a peculiar personal embodiment in his imagination” (JRRT, Of Fairy Stories, 82, quoted in MacLeod and Smol, 126). Tolkien called this his “invitational” style, while Smol and MacLeod describe it as his “painterly” style: that is, wanting the spectator to participate in completing the picture with their own interpretations. This approach to fantasy and Tolkien’s concern that the spectator should be allowed to participate in his art is reflected in his own drawings of scenes in The Hobbit and The Lord of Rings, which are often of landscapes where we still have to imagine the characters ourselves. To depict a scene too explicitly can close the process of imagination for the ‘spectator’ (how interesting, as noted by the authors, that Tolkien should use the word spectator rather than reader).

This enables one to better understand why J.R.R. Tolkien (and later Christopher Tolkien) had difficulty accepting any on-screen adaptations of his works. It was not merely purism, or disdain for ‘modern’ forms of story-telling that explains this reluctance, but rather a fundamental aspect of Tolkien’s imaginative philosophy. I have read criticism of Christopher Tolkien’s ‘possessiveness’ over his father’s legacy: should he not be glad to see it ‘brought to life’ on screen and made accessible to even more people? Such comments are ironic, of course, since it was precisely Tolkien’s wish to preserve a reader’s participation in the stories that contributed to his resistance to adaptation. On this theme, the article explains why Tolkien appreciated Pauline Baynes’ and Cor Blok’s illustations. Blok does depict Tolkien’s characters, but the simplicity of his work (a very difficult thing to achieve) prevents it from muscling in on our own interpretations. This reminds me of an old interview with renowned ‘Tolkien artist’ John Howe; according to him, deciding on what you won’t try to show in an illustration is as important as what you do show.

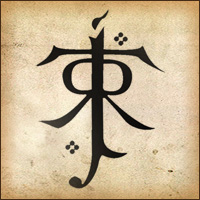

Finally, Smol and MacLeod discuss Tolkien’s ability to see art in writing. This is apparent from the beauty of the inscriptions on The Ring or the runes on Balin’s tomb. Given that is the case it makes sense that Tolkien was interested in Japonisme – Japanese pictorial script in which a character represents not just a letter but a whole word. The authors speculate that Tolkien may even have consulted Basil Hall Chamberlain’s ‘A Practical Introduction to the Study of Japanese Writing’ held in the Bodleian Library, and argue that Tolkien’s monogram of ‘JRRT’ “reveal the artistic influence of Japanese calligraphy”. They argue that Tolkien’s monogram was not just an efficient way to combine his initials but may also have been designed to connote a tree – both linguistically (in the Japanese script), and visually. In other words, his monogram could have been a multilayered “statement about his identity” (124).

Finally, Smol and MacLeod discuss Tolkien’s ability to see art in writing. This is apparent from the beauty of the inscriptions on The Ring or the runes on Balin’s tomb. Given that is the case it makes sense that Tolkien was interested in Japonisme – Japanese pictorial script in which a character represents not just a letter but a whole word. The authors speculate that Tolkien may even have consulted Basil Hall Chamberlain’s ‘A Practical Introduction to the Study of Japanese Writing’ held in the Bodleian Library, and argue that Tolkien’s monogram of ‘JRRT’ “reveal the artistic influence of Japanese calligraphy”. They argue that Tolkien’s monogram was not just an efficient way to combine his initials but may also have been designed to connote a tree – both linguistically (in the Japanese script), and visually. In other words, his monogram could have been a multilayered “statement about his identity” (124).

As with so much else in Tolkien’s work, this reflects a remarkable attention to detail, and a quest for meaning that does not always have to be announced and explained by word. I perceive this as respect for the mind and autonomy of the reader-spectator, contra criticisms that Tolkien’s work does not have room for emotional breadth or moral questions (for more context on this see Brenton Dickieson’s post on Phillip Pullman, which came along as I was mulling over this point). While the depth and detailed descriptions of Tolkien’s writing is pivotal to the success of his world-building, perhaps what is untold, hidden or even unknown by the author himself is just as important in fostering the reader-spectator’s curiosity and enchantment. Tolkien’s artwork is an example of the latter.

My thanks to the authors for their rich study and original conclusions, I would certainly recommend reading the article; Dr Anna Smol has also summarised it on her blog.

Images

- “Helm’s Deep & the Hornburg”. Tolkien sketched this on the back of an exam paper.

- Tolkien’s “The Forest of Lothlorien in Spring”

Texts

J.J. MacLeod, Anna Smol, “Visualizing the Word: Tolkien as Artist and Writer”, Tolkien Studies, volume 14, 2017, pp. 115-131

Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, The Art of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien. London: HarperCollins, 2011

Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, The Art of The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien. London: HarperCollins, 2015.

The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien and Humphrey Carpenter, HarperCollins, 1981.

Barbara Strachey, Journeys of Frodo: An Atlas of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Ballantine Books, 1981.

It strikes me that JRRT’s creative method, switching among media as he moment requires, would be impossible for someone writing with a word processor.

A fascinating insight!

Many thanks for your comment – I agree with Stephen, this is a very interesting thought! And makes me wonder if we need to rethink the media we use – is it even possible to switch back to paper these days? The word processor has many benefits, but it also comes with disadvantages – I don’t think we, ‘society’, have yet fully grasped how it has changed the way we write or even think. There are some interesting studies on the topic, but mainly in relation to memory and learning – I have to read into its impact on creativity a bit more. I wrote here a few months ago on ‘NaNoWriMo and Writing Freely’ exploring some of these themes, but I hadn’t connected drawing with the handwritten process back then. An interesting article on ‘A Mere Inkling’ also looks at the relationship between word processing, handwriting and creativity ( https://mereinkling.net/2018/01/18/pen-or-keyboard-a-literary-dilemma/ ). Thanks again.

I found this such a helpful short essay and wanted to express my appreciation. I especially liked your reference to language as a physical embodiment. It is so very different from the movement towards abstraction that besets our “hasty” use of language. I was thinking of Pullman and Brenton Dickieson’s excellent reflection before you made reference to it. Again it struck me that when Pullman lets his imagination lead he is as good as any story teller but when he puts his argument first he becomes clumsy. He is a controversialist in a way that Tolkien never is. Tolkien simply draws us into his world. His Catholicism is pre-Vatican 2 in which physicality and symbol were predominant. The language impacted on the hearer more as music does, being liturgical Latin. Pullman claims to hate this but he is at his best when he communicates more in this way. Of course Catholics also had the catechism and I have often been in awe when an older Catholic, sometimes with little formal education, is able to quote a complex theological formulation from memory, but I suspect that it is not the catechism that is loved.

On the question of the films I am struck that they begin to fade in my memory whereas the books and the pictures that I have developed by reading them, by dwelling within them, go ever deeper inside me as the years go by.

Many thanks indeed, Stephen, for this deep insight. Your comments (as well as Brenton’s) have persuaded me to have another go at reading Pullman’s work – partly to consider your observations and to identify comparisons between his work and those he criticizes. It is interesting what you say about the catechism, which suggests it is not just the meaning itself that is valued but the physicality of the words themselves. This may well be the case with other faiths too. Of course for a philologist, the shape of a word and its coming into existence through mere utterance, is precisely what fascinates. I suppose those two passions came together perfectly for Tolkien.

The films are one person’s (or several people’s) interpretations of the books, and I know many have taken joy from sharing in that – though I am critical of the films, I don’t wish to invalidate others’ appreciation of them. But I wholeheartedly agree with you, if one turns to the books, the memories and images grow over time and of course are personal. It is why reading/ hearing other’s reflections on the books is so enriching as they are implicitly attached to their own experiences.

Great piece of writing, Earthoak. I agreed with you on the fact of having visual effects to enhance your ideas and writing skill. The University idea greatly proves how sketching is. Writing is a Hobby which everyone should immerse themselves in. Also, when you have spare time, hit the sketchbook.

Thanks so much, for reading, and for the encouragement! 🙂 I have 2 pieces of finished artwork – I just haven’t had the time to write the accompanying blog post to go with them because it’s been such a busy time. But I made a commitment to write at least one post a month, and April is passing by, so I really should do this soon. Thank you for the nudge! I hope you’ll like the new drawing.